Are Option-Income Funds Here to Stay?

A long-term prediction for this year’s fund darlings.

Option-Writing Redux

I chuckled when I read Jason Zweig’s article in The Wall Street Journal, “Why Investors Are Piling Into Funds That Promise Not to Beat the Stock Market.” Jason and I are from the same era, toiling as investment-research cubs in the late ‘80s, and the investment strategy to which he refers, funds that sell call options, were a minor rage back then, too. What goes around comes around.

So, Jason knows whereof he speaks. You should read his piece directly—the link is not paywalled—because it covers more ground than I will summarize, but to provide his main themes:

1) Option-income funds own stocks and then sell covered calls against those equity positions.

2) They immediately distribute to shareholders the proceeds from their options sales, which are commonly regarded as “income” (although, as we shall see, they are not).

3) In addition to providing payouts that can reach as high as an annualized 11%, these funds also tend to be somewhat less risky than a stock market index fund.

What is not to like? Once again, Jason has the answers:

1) The funds’ “income” in fact consists of short-term capital gains, which are typically taxed at a higher rate than equity dividends.

2) As his headline states, over time such funds will likely post lower total returns than will the stock market.

All sound information, but as always there is more to be said about the topic.

Different Animals

The biggest item is implied by this column’s lead. We have been here before. Which raises the question: If option-writing funds were popular 35 years ago, why have they only recently been rediscovered? After all, index funds were just starting to get traction 35 years ago, and they did not disappear for the next three decades. Quite the contrary. They steadily grew their market share, year after year.

One answer is that today’s option-writing funds are different from those of the past. The 1980s version mostly consisted of government bonds. Fund marketers thought (very much correctly) that investors regarded all government-bond funds as being equally safe, so why not just select the fund that paid the highest “income”? They therefore created “government plus” funds that supplemented their true yields with short-term capital gains generated by selling call options.

This investment approach satisfied shareholders for a while, until they realized that such funds inevitably eroded capital. When bond prices rose, the funds’ best-performing securities were likely to be called away. That limited their ability to participate in market gains. During bear markets, though, nobody called the funds’ losing bonds. The only protection the funds enjoyed was from the proceeds of their options sales—which they had already distributed to shareholders.

In other words, the performance of the funds’ net asset values was asymmetrical. When bond prices rose, their net asset values only received part of the gain. However, when bond prices fell, their net asset values suffered every penny of the loss. Another way of stating the matter is the funds gradually shrunk their principal because they distributed more than they earned. Their “income” exceeded their total returns.

But the Same Concern

Although today’s option-writing funds stand a better chance of preserving their net asset values, because equities, unlike government bonds, tend to grow their capital over time, the danger persists. Almost certainly, the largest-paying option-income funds, such as those distributing the 11% rate mentioned in Jason’s article, will suffer principal erosion. The U.S. stock market itself is unlikely to post an 11% annualized gain, never mind funds that are willing to concede some total returns in exchange for call-option proceeds and lower volatility.

Let’s examine how option-income funds have performed. Morningstar calls these funds “derivative income” to address the fact that some of them simulate options-writing strategies by using other forms of derivatives, so I will use that term in describing the funds. But they are the same funds that Jason discusses.

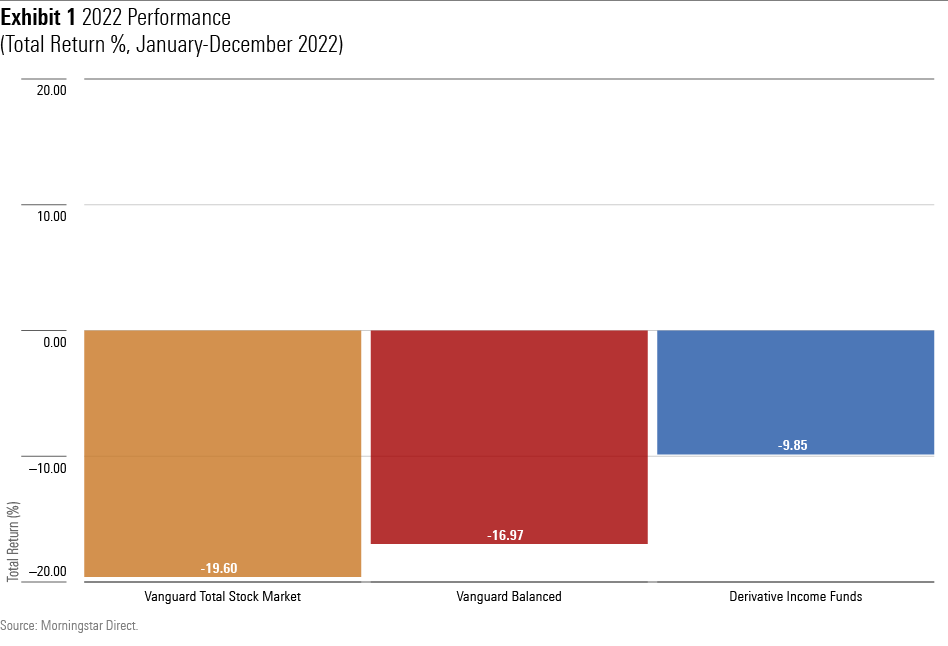

First, their 2022 results, as compared with my usual touchstones of Vanguard Total Stock Market Index VTSMX (representing, duh, U.S. equities) and Vanguard Balanced Index VBINX (representing a lower-risk version of equities that might be more comparable with derivative-income funds).

A triumph for derivative-income funds! Which, of course, is why the group has become fashionable (Investors rarely, if ever, flock to fund categories that have recently flopped.) As is well known, 2022 not only punished stock funds but was historically harsh on traditional balanced strategies, as with Vanguard’s funds. Consequently, derivative-income funds thrashed their mainstream rivals.

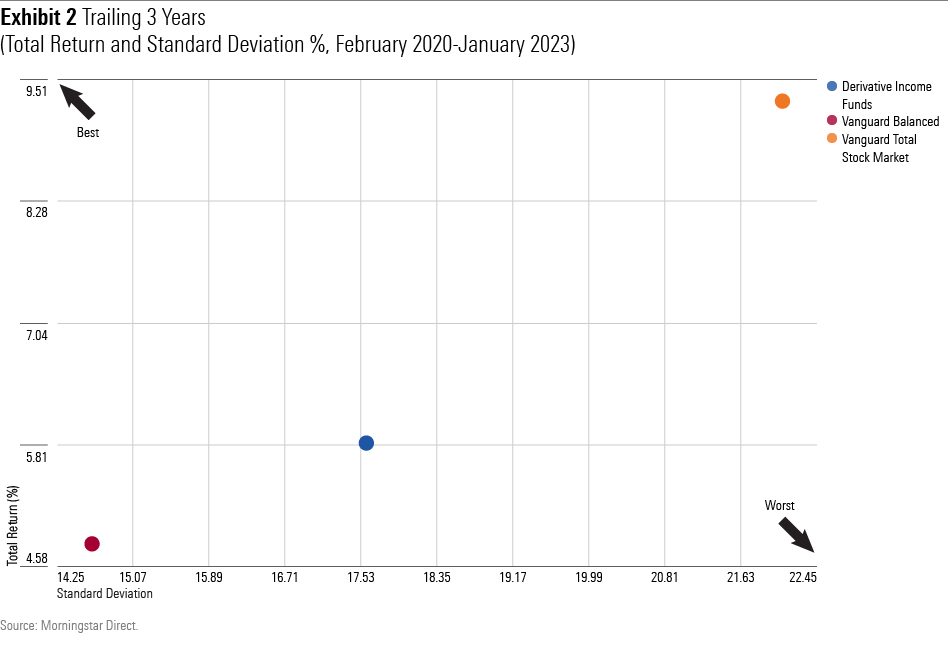

So far, so good. But one year does not a track record make. Expanding the view to three years changes the outlook. The exhibit below is somewhat trickier to interpret, as it includes the second variable of standard deviation. But it would be unfair to compare derivative-income funds directly to either the equity market (which is more volatile) or to Vanguard Balanced Index (which, last year aside, is usually less volatile.)

The short version of explaining the chart is that the strongest results land in the upper left corner, which represents high returns and low risk, while the weakest results place in the lower right. Thus, derivative-income funds were slightly behind their two competitors—a surprising outcome, given that they scored such a resounding victory during one third of that period.

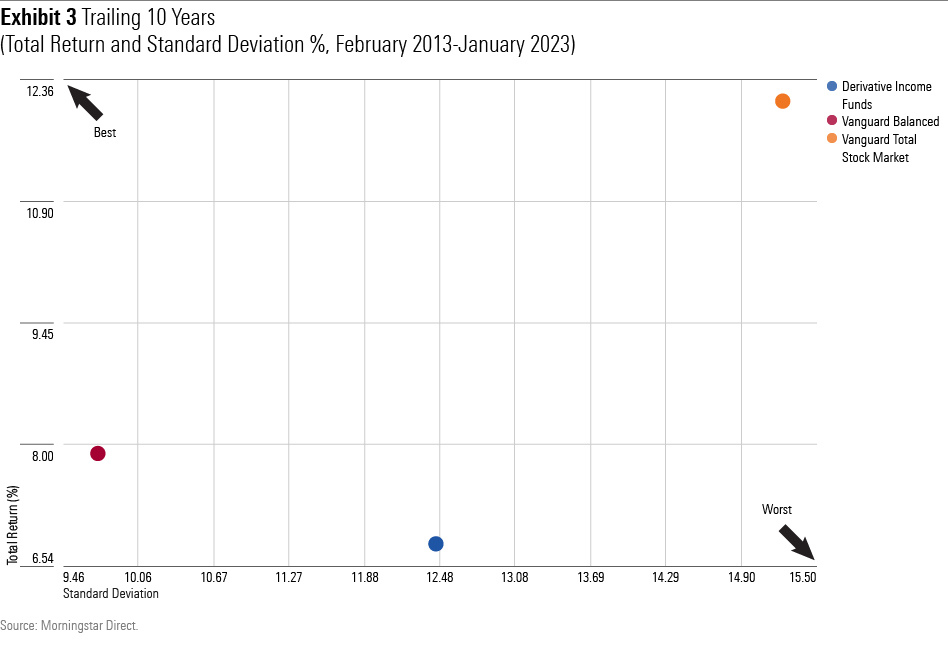

Finally, the 10-year totals:

Not much need to be said. Admittedly the sample size is small, because only nine U.S. based derivative-income funds existed 10 years ago, but the conclusion is simple: Last year’s heroes have been anything but remarkable over a full decade. On average, any fund that has distributed more than 7% of its annual value is worth less today than it was in early 2013.

Summary

As Jason Zweig writes, the evidence for option-income funds (to use his term) is not entirely negative. They thrive under certain conditions, such as choppy markets that fall as much as they rise, and—as in 2022—when high-quality bonds fail to hedge equity portfolios. Overall, though, I suspect that they will eventually disappoint their shareholders. They may well decide that the bird in the hand is not, in fact, worth two in the bush.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)