How Higher Retirement Savings Limits Can Help You Catch Up

Even if you’re off to a late start, there’s still hope for your 401(k).

A couple of years ago, I wrote a piece focusing on Fidelity’s age-based retirement savings targets, which are based on a dollar amount equal to a certain multiple of salary at different ages. I ran a simple year-by-year test to see how the numbers might play out in practice based on the assumptions Fidelity used, which were 1.5% real wage growth per year, a savings rate equal to 15% of salary, retirement at age 67, and an income replacement target of 45% of preretirement income. I also assumed that retirement-plan contributions started at age 25 and continued consistently until retirement.

Not surprisingly, a hypothetical investor who followed these guidelines should be in decent shape for retirement. But those who weren’t able to start saving until later in their careers often find themselves behind—and last year’s market rout made matters worse for most retirement savers.

The good news: Investors now have additional leeway to funnel more assets into retirement savings. In this article, I’ll delve into how higher savings limits for 401(k) plans can help savers catch up.

How Higher Retirement Savings Limits Can Help

Starting in 2023, employees under the age of 50 can contribute up to $22,500 per year to a company-sponsored 401(k) plan, up from $20,500 in 2022. Participants who are age 50 or older can contribute an additional $7,500 per year in “catch up” contributions, raising the total contribution limit (not including any employer contributions) to $30,000 per year. These higher limits can help savers make significant progress toward shoring up retirement savings.

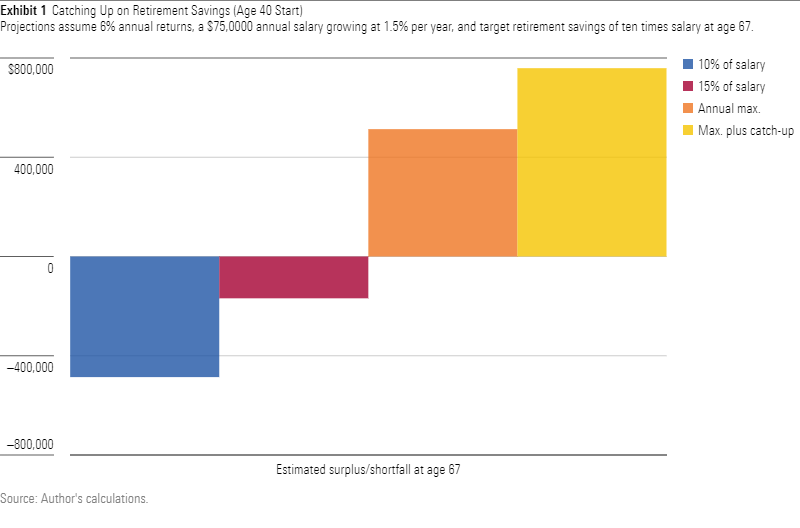

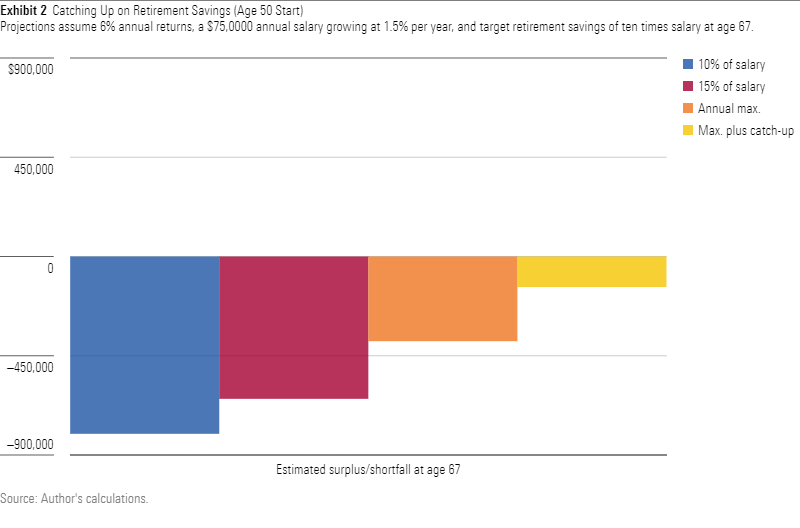

In the two examples below, I’ll start with a hypothetical investor with a $75,000 salary at age 40, with earnings increasing by 1.5% per year. The first example assumes the investor starts out with no retirement savings at age 40, and the second assumes no retirement savings until age 50. In both cases, I compared the estimated balance at age 67 using four different annual savings levels: 10% of salary, 15% of salary, up to the annual maximum, and up to the annual maximum plus catch-up contributions starting at age 50. The surplus or shortfall amount compares the estimated balance at age 67 (based on an estimated return of 6% per year) with an age-based savings target of 10 times salary by age 67. The numbers below do not assume any employer contributions, which can also go a long way toward closing the gap in retirement savings.

Retirement Savings Catch-Up: Age 40 Start

A person who began contributing to retirement savings at age 40 might not fully catch up, even after consistently carving out 10% or even 15% of each year’s salary for retirement over the next 27 years. Assuming a 6% annual return and annual contributions equivalent to 10% of salary, she would end up more than $400,000 shy of Fidelity’s age-based target of $1.1 million (which is equivalent to 10 times an assumed salary of about $112,000 at age 67). With annual contributions equivalent to 15% of salary, the shortfall would narrow to about $168,000 at age 67.

The picture looks brighter, though, for an employee who’s able to boost contributions to the annual IRS limit. Assuming consistent annual contributions of $22,500 per year, our hypothetical investor would actually end up roughly $500,000 ahead of the age-based salary target. That surplus could provide a margin of safety for additional expenses late in life, such as long-term care, or a potential legacy that could be left to children, grandchildren, or charity after death. The extra cushion would be even more generous for someone who maxed out retirement savings until age 50 and also took advantage of catch-up savings after that point.

Retirement Savings Catch-Up: Age 50 Start

It’s more difficult to fully catch up at this age by using retirement-plan savings alone. A person who started contributing 10% of his salary to retirement savings at age 50 would still be well short of target levels by age 67. I estimated a portfolio value of roughly $320,000 at age 67, compared with the age-based target of $1.1 million. Consistently saving 15% of salary starting at age 50 would lead to an estimated shortfall of about $645,000, and even ramping up annual contributions to $22,500 per year would lead to an estimated shortfall of about $384,000 at age 67.

But taking full advantage of catch-up contributions by consistently saving $30,000 per year from age 50 through age 67 would lead to a smaller shortfall of roughly $140,000.

While waiting until age 50 to start saving for retirement is far from ideal, maxing out annual savings can get investors reasonably close to the target level by retirement.

Conclusion

The assumptions I’ve used here may not be realistic for every retirement saver. Investors who are behind on saving for retirement might lack the income security or other resources needed to start saving, which can persist over multiple decades. And investors who didn’t start saving for retirement early in their careers might find it difficult to start saving significant amounts every year starting at age 40 or 50. That’s particularly true for lower-income savers, who often need to funnel most of their earnings toward other financial priorities, such as paying off student loans or meeting basic living expenses, such as food, clothing, shelter, transportation, and insurance.

Market performance is another unknown. I assumed annual returns of 6% each year, but actual returns can vary significantly from year to year. The sequence of returns also plays a significant role in ending portfolio values at retirement. A negative sequence of returns can be particularly damaging if it happens close to retirement. There are two main reasons: First, investors have more dollars at risk during the period of negative returns. And second, their portfolios have less time to recover once the market eventually bounces back.

As a general guideline, though, the projections above illustrate the benefits of starting early, as well as the potential boost from more generous contribution limits.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)