How Active Is Your Passive Bond Fund?

Degrees of active management even exist in index funds.

The difference between active and passive management is better described as a spectrum than a dichotomy. Degrees of active management even exist in index funds, particularly with regard to fixed-income strategies. In this article, I will go over some of the main ways bond index portfolio managers utilize discretion. These measures address the constant trade-off between tracking error and transaction costs and aim to keep tracking performance in check rather than add unnecessary risk.

Constructing the Portfolio

While holding the entire index portfolio should theoretically minimize tracking error, the transaction costs from buying and selling all of the securities can ultimately detract from tracking performance. This dilemma is particularly problematic in the fixed-income space, where the market is much larger and more fragmented and indexes can include thousands of bonds.

The sheer size of the bond market poses a challenge for portfolio managers. Most companies tend to have a single share class of stock, but they can issue multiple bonds with varying maturities, coupons, and credit ratings. This vastly increases the pool of tradable bonds compared with stocks and, by extension, the number of constituents in a broad market index. This has two implications for the funds tracking them. First, newer index funds with limited assets might not be able to hold all of the constituents in the index. Second, the costs associated with trading all of the securities in a bond index can be much more prohibitive than for an equity index.

Thus, portfolio managers must constantly weigh the incremental benefit of owning an index constituent against the cost of executing the trade. Except for most Treasury or Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities funds, where the index lineup is short and highly liquid, most bond funds leverage stratified or representative sampling instead of full replication.

Sampling typically involves dissecting the index portfolio into buckets based on risk factors such as credit, duration, sector, or geography. Subasset classes require consideration of additional factors such as prepayment risk for mortgage-backed securities or revenue sources for municipal bonds. The fund then holds a subset of securities that are representative of the risk characteristics of the index portfolio. Portfolio managers continuously monitor and adjust the risk/reward characteristics of the portfolio against its benchmark to remain within risk parameters, particularly tracking error.

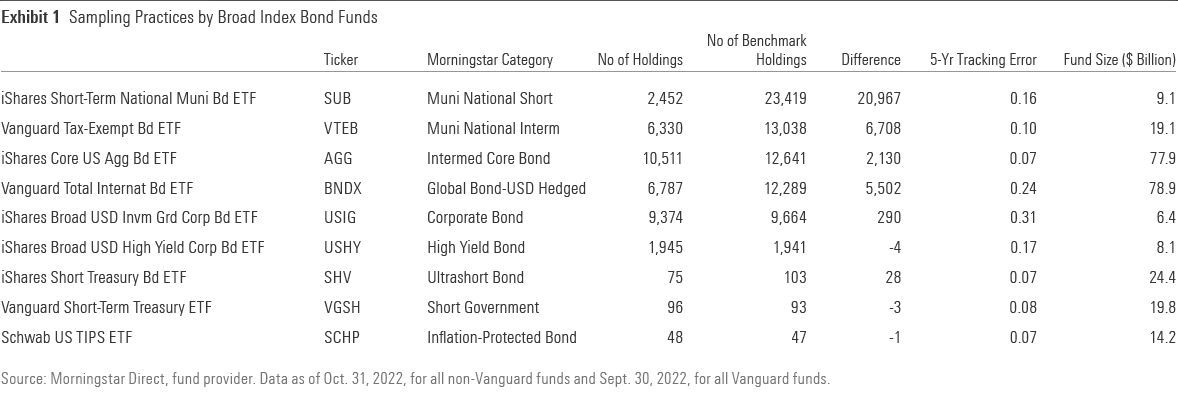

Exhibit 1 displays the number of holdings for several broad-market index bond funds compared with those of their underlying indexes. Typically, the larger the benchmark index, the more sampling is performed by the fund. Many indexes were created with investability in mind, but the lineup of a broad bond index can still easily climb into the thousands. Thus, it’s impractical for most index-tracking funds to replicate a portfolio of this size, particularly funds with a smaller asset base. For instance, iShares Short-Term National Muni Bond ETF SUB, which has $9 billion under management, holds only 10% of the underlying index’s portfolio. Its intermediate municipal counterpart, Vanguard Tax-Exempt Bond ETF VTEB, is able to capture around half of its index’s portfolio thanks to its larger asset base of $19 billion.

While much of the bond market’s returns can be traced back to the systemic risk factors used in sampling models, areas with more idiosyncratic risk can pose more challenges. In these corners of the bond market, portfolio managers often aim to capture as much of their index’s portfolio as their asset base allows in order to minimize tracking error. For instance, both iShares Broad USD Investment Grade Corporate Bond ETF USIG and iShares Broad USD High Yield Corporate Bond ETF USHY hold most of their benchmarks’ constituents despite smaller fund sizes.

It’s worth noting that despite differences in degree of replication, all of these funds manage to maintain low tracking error against their benchmarks. Case in point, the two municipal funds on the list kept their tracking error below 20 basis points, and they tend to perform the same as their benchmarks, before fees.

Trading the Portfolio

Trading for index funds can be quite different from their active counterparts, particularly for index exchange-traded funds. The in-kind creation/redemption mechanism—the main structural difference of the ETF wrapper and the source of its tax advantage over mutual funds—gives index portfolio managers another lever to pull.

Instead of only trading directly with the market in cash like a mutual fund manager, an ETF manager may transact with authorized participants in the primary market by exchanging ETF shares for a basket of securities (hence, the in-kind moniker). Before 2019, most index ETFs were required to use a basket that included a full slice of the fund portfolio with pro rata weights every time they transacted with APs. Sourcing liquidity for all of these securities can be costly. This is particularly an issue if the basket includes illiquid bonds or small nominal trades, as transaction costs increase when trade size decreases [1]. Since APs participate in the primary market because of the arbitrage opportunity rather than out of contractual obligations, higher costs reduce their willingness to create or redeem shares, affecting the efficiency of the creation/redemption process.

In September 2019, the SEC adopted rule 6c-11, which permitted the use of custom creation/redemption baskets for most fund providers [2]. ETF managers can trade subsets of securities from their portfolios with custom weights; this was previously something only available to a small subset of ETFs that came to market before 2006. The fund still provides a representative basket of the portfolio daily, but portfolio managers and APs can negotiate changes to the basket that fit the needs of both parties. This gives portfolio managers another tool for managing cash flows or rebalancing while improving engagement with APs and market makers. The managers make the final call on whether to accept the negotiated basket of securities.

This allows the fund to transact in the primary market as much as possible and avoid the transaction costs inherent to the secondary market. It can also provide more flexibility for portfolio managers to manage the fund’s risk characteristics, especially when opportunities arise to align their sampled portfolios closer with their indexes. Negotiating baskets with APs has led to concerns about potential conflicts of interest, but any unusual transactions would result in tracking error observable by the fund’s risk committee and investors alike. Thus, it’s in fund providers’ best interest and is best practice for risk managers to monitor the in-kind baskets exchanged in the primary market and the managers’ relationship with APs.

Outside of creations and redemptions, portfolio managers running large portfolios can also utilize portfolio trading. This packages multiple bonds together into a single block trade. Instead of executing each trade individually, traders can get a quote from dealers for all the securities in one bundle. This is particularly helpful for index rebalancing when portfolio managers need to adjust exposure to a large swath of securities or for downgrades/upgrades to a company that require wholesale position changes.

Portfolio managers are required to review and can choose the best execution price offered to them, alleviating transparency concerns. In addition, effective May 2023, members of the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority will also be required to report portfolio trades in corporate bonds to the trade reporting and compliance engine. This is another step in the growing effort to increase transparency in the bond market.

Index-Tracking Performance Is King

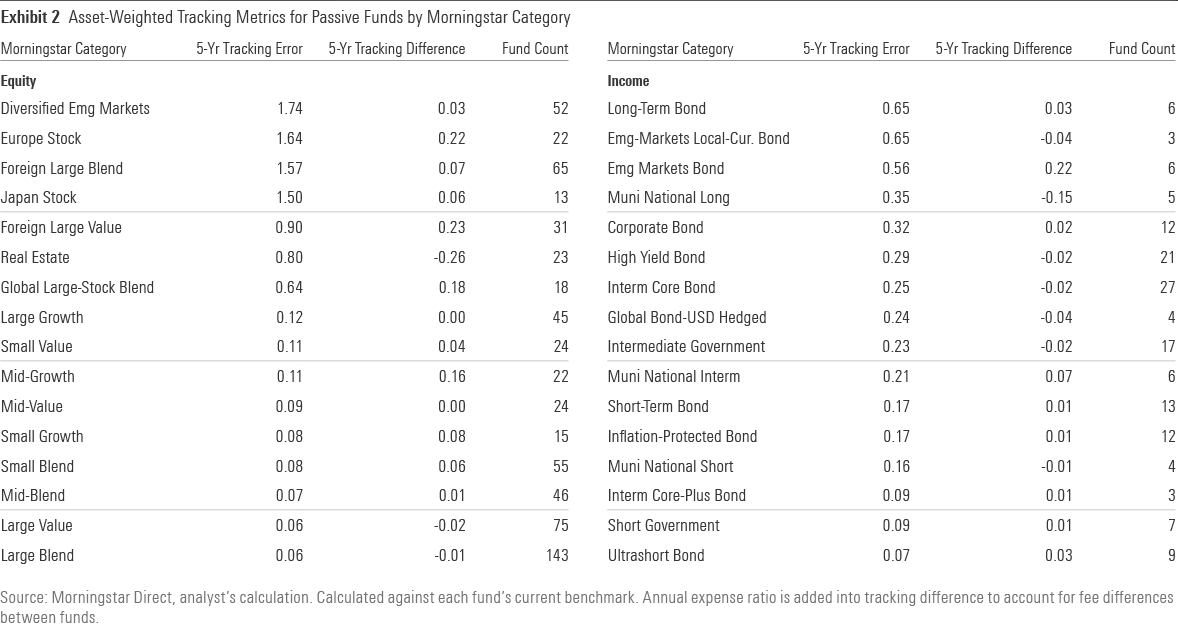

Exhibit 2 displays the asset-weighted tracking performance for index funds in several Morningstar Categories. Metrics are calculated for each fund against its current primary prospectus benchmark and weighted by the fund’s share of the category’s aggregate assets under management. Tracking error is the standard deviation of the difference between the returns of the fund and its benchmark. Tracking difference measures the difference between these returns with fees added back in before averaging. This calculation does not account for historical index or fee changes or sample size bias, but the results are in line with expectations of tracking performance across different subasset classes.

Passive domestic-equity funds maintain the lowest tracking error, but most bond-fund categories aren’t far behind. Outside of the less-liquid long-term and emerging-markets bond categories, the asset-weighted average tracking error remains within 35 basis points for each bond category, while the average tracking difference before fees is minimal. Ultimately, all of the discretion taken by passive bond managers points back to tracking metrics, as these metrics can easily uncover flaws in a fund’s implementation.

[1] Bessembinder, H., Spatt, C., & Venkataraman, K. 2020. “A Survey of the Microstructure of Fixed-Income Markets.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis. https://www.sec.gov/spotlight/fixed-income-advisory-committee/survey-of-microstructure-of-fixed-income-market.pdf

[2] “SEC Adopts New Rule to Modernize Regulation of Exchange-Traded Funds.” https://www.sec.gov/news/press-release/2019-190

This article first appeared in the November 2022 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c00554e5-8c4c-4ca5-afc8-d2630eab0b0a.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c00554e5-8c4c-4ca5-afc8-d2630eab0b0a.jpg)