Active Management’s 2022 ‘Triumph’ Is a Mirage

Dunn’s Law reveals the true story.

At Last, Active Funds?

My friend Bill Bernstein forwarded me an article from The Economist that states, “Passive funds that indiscriminately bought everything, including stocks which seemed overpriced, prospered. But in 2022 rising interest rates brought the trend to an abrupt halt. Investors who had hunted for stocks that were cheap relative to their fundamentals were at last rewarded.”

The Economist speaks for the consensus. Bill writes that he has been swamped with calls from reporters seeking comments about the failure of passive investing, and how actively managed U.S. equity funds finally scored their revenge. As Bill notes, though, actively run U.S. stock funds did not rebound, relatively speaking, in 2022. Their apparent success is an illusion.

Dunn’s Law

To explain: During the 1990s, an amateur investor (and professional lawyer) named Steve Dunn asserted that conventional discussions of U.S. equity-fund performances were misleading. Typically, such assessments compared a fund’s return with that of “style benchmark.” If, for example, a small-cap value fund gained 10% on the year, while the small-value stock index was up 8%, then the fund was said to have beaten its benchmark by 2 percentage points.

That analysis was fine as it went, said Dunn, but it missed a key point. Actively managed funds are less pure than their style benchmarks. Style indexes contain only what the label promises. Active funds operate differently: Small-value funds mostly own stocks that fit their description, but they also invest in midsize or even large companies, as well as some pricier businesses.

Consequently, comparing active funds against their style benchmarks is insufficient. Consider the above example, when the small-value stock index returned 8%. If that 8% gain was the weakest result among the style indexes, then the average actively run small-value fund would inevitably have beaten its benchmark. After all, any investments that small-value funds made outside of their stated area—securities that they would hold, but the benchmarks would not—would likely help them.

So was born Dunn’s Law: There is an inverse relationship between the performance of active managers and the performance of the segment of the stock market that they represent. When Dunn’s Law is properly applied, active fund managers in aggregate (of course, there are always individual exceptions) no longer have “good” and “bad” years. The managers’ results pretty much always match those of the indexes, before considering the effects of cash and expenses.

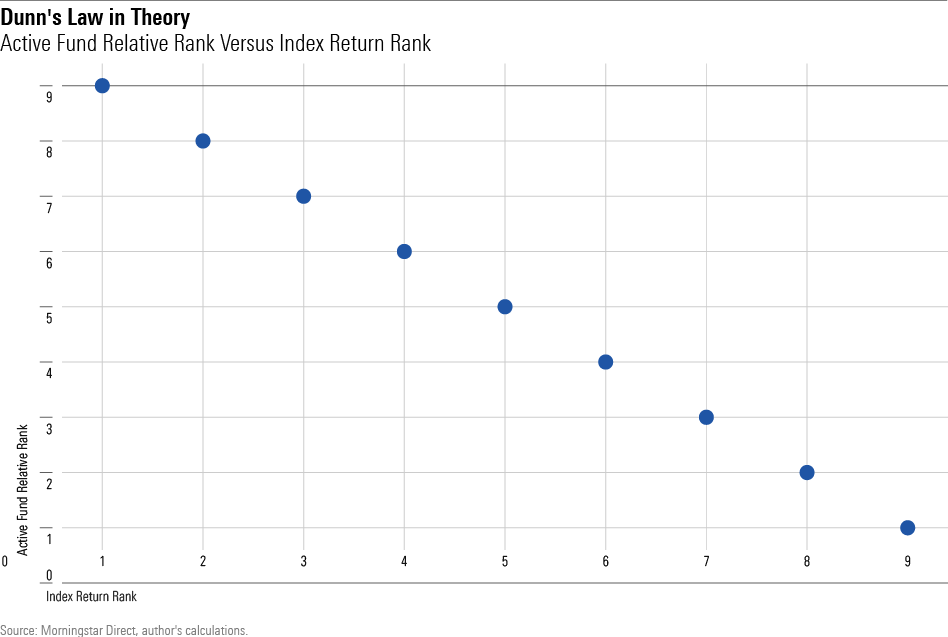

In Theory

The following graph shows the expected results under Dunn’s Law. Morningstar places all U.S. diversified equity funds into one of nine “style-box groups,” ranging from large-growth for the nation’s biggest and priciest companies to small-value for the cheapest and most obscure securities. if the relative performance for each of the group’s active funds is ranked and then compared with the index returns for each of those nine groups, the relationship will be, per Dunn’s Law, inverse. The scatterplot will move from the upper left to the lower right.

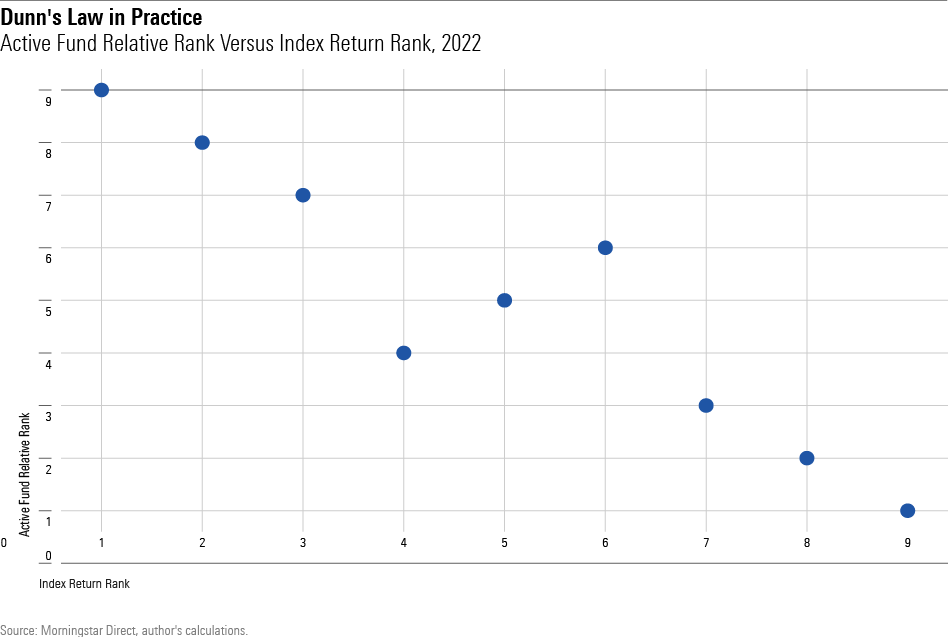

In Practice

The next graph shows the actual 2022 rankings. These are based on the oldest share class for all actively run U.S. equity mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (although there are very few of the latter, since index funds are excluded).

Very close! What’s more, the index results for the middle dots, which display the three core-stock categories—large-core, mid-core, and small-core—were almost identical, landing within 0.10 percentage point. (For the indexes, I used Morningstar’s US Market style series.) Change a few basis points and the real-world diagram would have exactly matched the theoretical picture.

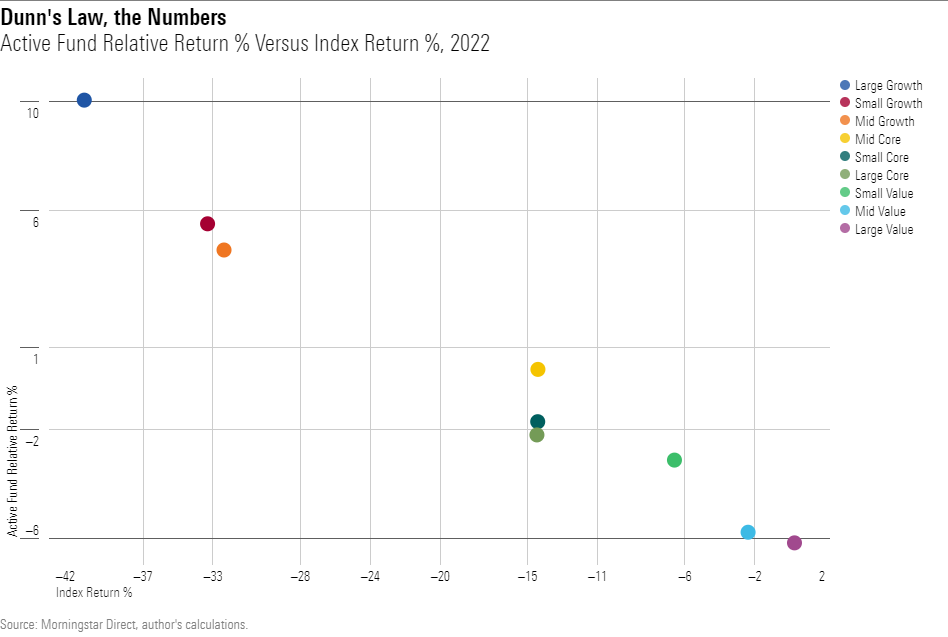

Here is the same chart redrawn, this time using returns rather than rankings.

Once again, the outcome is just as Dunn foresaw. This time, the dots show magnitude as well as rank order. That is, the large-growth dot on at the upper far left is much higher than any other dot, because large-growth stocks performed much worse. They lost 40.3% for the year, while the next-worst style benchmark of small-growth fell 33.3%. The blend and value indexes were better yet. Consequently, large-growth funds were not only likely to beat their benchmarks, but to crush them. That they did, by an average margin of 10 percentage points.

In five of the nine categories, active funds trailed their benchmarks. The losing margins for the weakest two categories, large-value and mid-value, were virtually identical to the winning margins of the second- and third-strongest categories, mid-growth and small-growth. In other words, aside from large-growth funds, which benefited mightily from owning anything outside their sector, there is no evidence that actively managed funds thrived in 2022. Dunn’s Law scotches that thesis.

A Single View

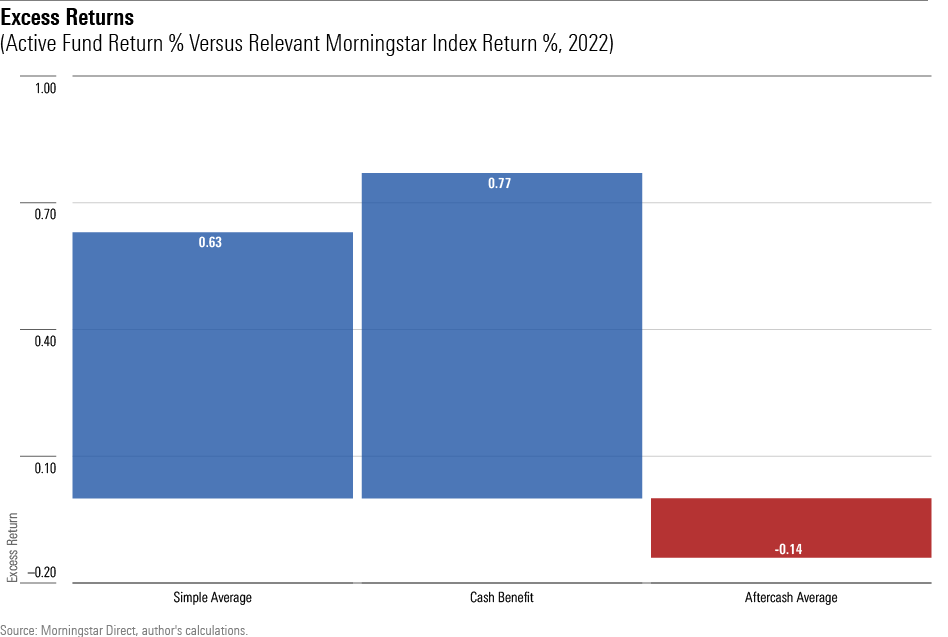

Let’s combine those nine data points. Weighting the relative category returns by the number of funds within each of those categories yields an industry average of 0.52%. That is, actively run funds in aggregate bettered their style benchmarks by half a percentage point. However, the benefit that active funds accrued from holding their customary cash positions was larger yet. Thus, after considering fund cash, active U.S. equity funds by this measure trailed their benchmarks.

This finding is certainly not the last word. It is subject to an error term that is impossible to compute but would surely be meaningful. Also, as those results are after fund expenses have been paid, they indicate that the stocks selected by active U.S. equity fund managers did slightly best the market indexes. (Once again, this statement is subject to the error-term caveat.)

Active managers often achieve that feat, though. Before accounting for expenses, the average trailing 15-year return for actively run large-blend funds exceeds that of both the Morningstar US Market Index and Vanguard Total Stock Market Index VTSMX. (Admittedly, those figures do include the effect of survivorship bias.) However, active funds did not score higher returns after accounting for their costs. That precept holds for the long run—and, it seems, also in the “exception” of 2022.

Correction: The article was updated with a corrected versions of the first three exhibits.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MFL6LHZXFVFYFOAVQBMECBG6RM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EGA35LGTJFBVTDK3OCMQCHW7XQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)