Should Investors Be Worried About the United States Debt Ceiling Crisis?

A default on United States government debt owing to the debt ceiling isn’t likely, but should one happen, here’s what the damage could look like.

The Congress fight over raising the government debt ceiling is likely to augment market volatility over the next six months. Fortunately, we expect the issue to be resolved before any damage is done, and the possibility of a default on U.S. government debt is extremely low. In the event of a default, all bets are off, but the potentially catastrophic damage wrought by such a scenario means that investors shouldn’t ignore this issue entirely. If the worst does happen, there are few good options for investors.

What is the Federal Debt Ceiling, also Known as the Debt Limit?

First, what is the debt ceiling? When the United States Congress enacts plans for federal spending, it doesn’t automatically authorize additional debt needed to pay for spending in excess of revenue. Instead, a separate process must periodically occur where Congress raises the limit on the U.S. debt outstanding.

For decades, this procedural quirk incited little legal challenges and turmoil in Congress, but this started to change in the 1990s as the debt limit became the arena for partisan squabbling. This reached a fever pitch in 2011 during the Obama administration, when fiscally hawkish House Republicans blocked the legislation for the raising of the debt ceiling for several months. To be clear, raising the debt limit itself authorizes no additional spending—it merely allows debt to be issued to pay for spending that had already been passed. But policymakers have sometimes sought to use the debt limit as negotiating leverage in order to force through spending cuts.

A deal was ultimately reached to avert crisis in 2011 but not before sparking fears for several months that a cash-strapped U.S. Treasury would be forced to default on payments of interest or principal on maturing debt.

How the Federal Debt Limit Debate Will Play Out under McCarthy and Biden

With Republicans having recaptured the House last November, this year brings many of the same circumstances as the 2011 debt limit standoff. Indeed, it has been reported that new House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, in order to secure support from his caucus to become speaker, made a pledge to not raise the debt ceiling without massive cuts in federal spending.

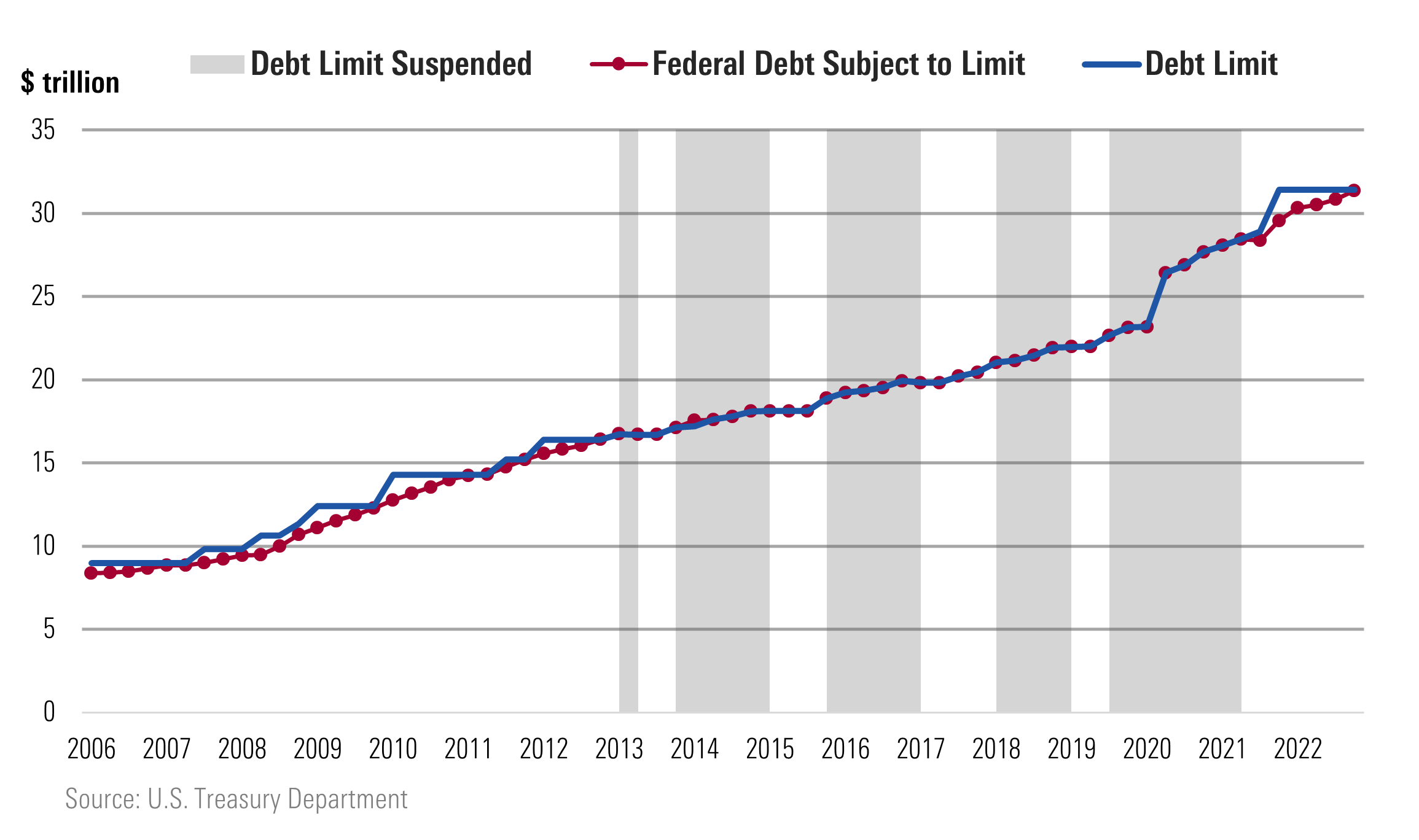

So, what will the next several months bring to the country? The U.S. actually already hit its debt limit at $31.4 trillion on Jan.19. That doesn’t mean that a debt limit-caused financial crisis has arrived, however. For the time being, the federal government can meet its funding needs using its roughly $300 billion of cash on hand plus other “extraordinary measures.” Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has advised that the cash could run out as soon as early June, at which point default would become a strong possibility.

We believe that a majority of House members in Congress would prefer to raise the debt ceiling without any uproar, as there is little political upside in plunging the U.S. economy into crisis, given the slower performance of the stock market right now. But without approval from McCarthy, a bill to increase the debt limit can’t reach the House floor through the usual channels. The problem lies in the fact that McCarthy needs nearly unanimous support among House Republicans in order to maintain his position. Perversely, the slim margin of the Republican majority (222 to 212) means that McCarthy is beholden to the furthest right members of the Republican caucus, and these policymakers are vociferously against raising the debt ceiling without sweeping spending cuts.

The prospects of a deal being reached that would placate Democrats as well as the most extreme House Republicans look dim. The Biden administration is likely to insist on tax increases to go along with spending cuts in any deal, which would be anathema to the Republicans.

This would all seem to portend for no resolution for the debt limit crisis. However, there is a way for House Democrats to join with moderate Republicans to get the debt ceiling lifted without approval from McCarthy. This is an arcane procedure called the “discharge petition.” A simple majority is enough for the discharge petition to work, meaning only six Republicans would need to join the 212 Democrats. We believe that a discharge petition is overwhelmingly likely to succeed—either as a direct vehicle to bring the debt limit bill to the floor or by pressuring McCarthy to assent to a face-saving compromise. House members and their staff are already laying the groundwork for a discharge petition. Biden and McCarthy had their first meeting to discuss the debt ceiling on February 2, so the leverage provided by the discharge petition is already bringing McCarthy to the negotiating table.

Because of the nature of the procedure, the discharge petition route will take several months to execute fully. But we should have clarity sooner rather than later that the discharge petition is likely to be successful (whether on its own or as leverage).

We expect this effort to produce a two-year suspension of the debt limit, meaning the issue will disappear as a concern until the next Congress, in 2025.

Implications of the Current Debt Ceiling News for the U.S. Economy and Investors

The most likely outcome is a smooth resolution of the debt ceiling crisis. That said, given unfamiliarity with the discharge petition procedure, it wouldn’t be surprising to see some market volatility until the issue is fully resolved.

In the off chance that the discharge petition fails or a debt limit legislation can’t be reached in time, Washington policymakers have speculated on ways to avoid an outright default once the U.S. Treasury runs out of cash. Possible solutions include minting a “trillion-dollar coin,” issuing Treasury debt at a large premium to face value, or invoking the 14th amendment to ignore the debt limit entirely. All of these proposed solutions involving the Treasury are legally questionable, and the lack of certitude would hardly soothe the market. In a scenario where a deal isn’t reached at first, it’s more likely that we’d see a large selloff in U.S. Treasuries, which shocks Congress into finally fixing the problem.

Other than the prospect of default, there’s another way the debt ceiling issue could hurt the economy and markets. Back in 2011, the legislation that finally lifted the debt ceiling entailed significant cuts of U.S. federal spending, amounting to about 0.75% of gross domestic product. This negative fiscal shock dragged on an economy that was still ailing from the aftermath of the Great Recession. However, this isn’t a problem this time around. The “discharge petition” route probably won’t lead to large spending cuts. And even if they did occur, the Federal Reserve has room to cut interest rates in order to offset a negative fiscal shock.

What about the worst-case scenario, where a significant and prolonged default on U.S. Treasury debt does occur? The outcome could be horrific, but in truth it’s hard to say exactly what would happen.

We can try to get a clue on how markets would react by looking at the 2011 debt ceiling crisis, but this provides only marginal insight. Treasury yields actually fell in the months prior to the 2011 lifting of the debt ceiling, probably because of the impact of other macroeconomic factors like the eurozone crisis.

Another spat over the debt ceiling in 2013 led one-month Treasury bill yields to briefly shoot up by 30 basis points relative to one-year yields. This means that investors were worried about soon-to-be maturing debt failing to be repaid. But this yield spike faded within days, and it never showed systemic impact in bond markets.

What Happens if the U.S. Defaults on its Government Debts?

It’s safe to say that markets have never priced in more than a very low probability that the debt ceiling crisis causes a major default. Should such a debt default occur, then we are in uncharted waters in terms of market and economic impact.

Presumably, Congress would ultimately step in to lift the U.S. debt ceiling after weeks of chaos. It could even make Treasury investors whole by paying up on missed payments and accrued interest. It’s quite possible then that markets could shrug off the default as a temporary, technical error. But it’s also possible that the default could lead to severe and irreparable damage.

Securities issued by the U.S. Treasury have long performed as a safe haven asset, and because of that attribute, they carry a very low yield compared with the expected return on investing in stocks and other risky assets. But these Treasury bills, bonds, notes are a safe haven in large part because investors think they are a safe haven. Most other developed countries’ government bonds also benefit from such a dynamic, although to a lesser extent than the U.S., which has the special role of serving as the global reserve currency.

But a large enough shock, such as defaults from the debt ceiling impasse in 2023, could cause this self-reinforcing process to run violently in the other direction. Not only would investors’ loss in confidence feed on itself but also rising yields would eventually cause an increase in the federal government’s interest expense. This would cast doubt on the U.S. government’s fiscal health, leading to further increases in yields.

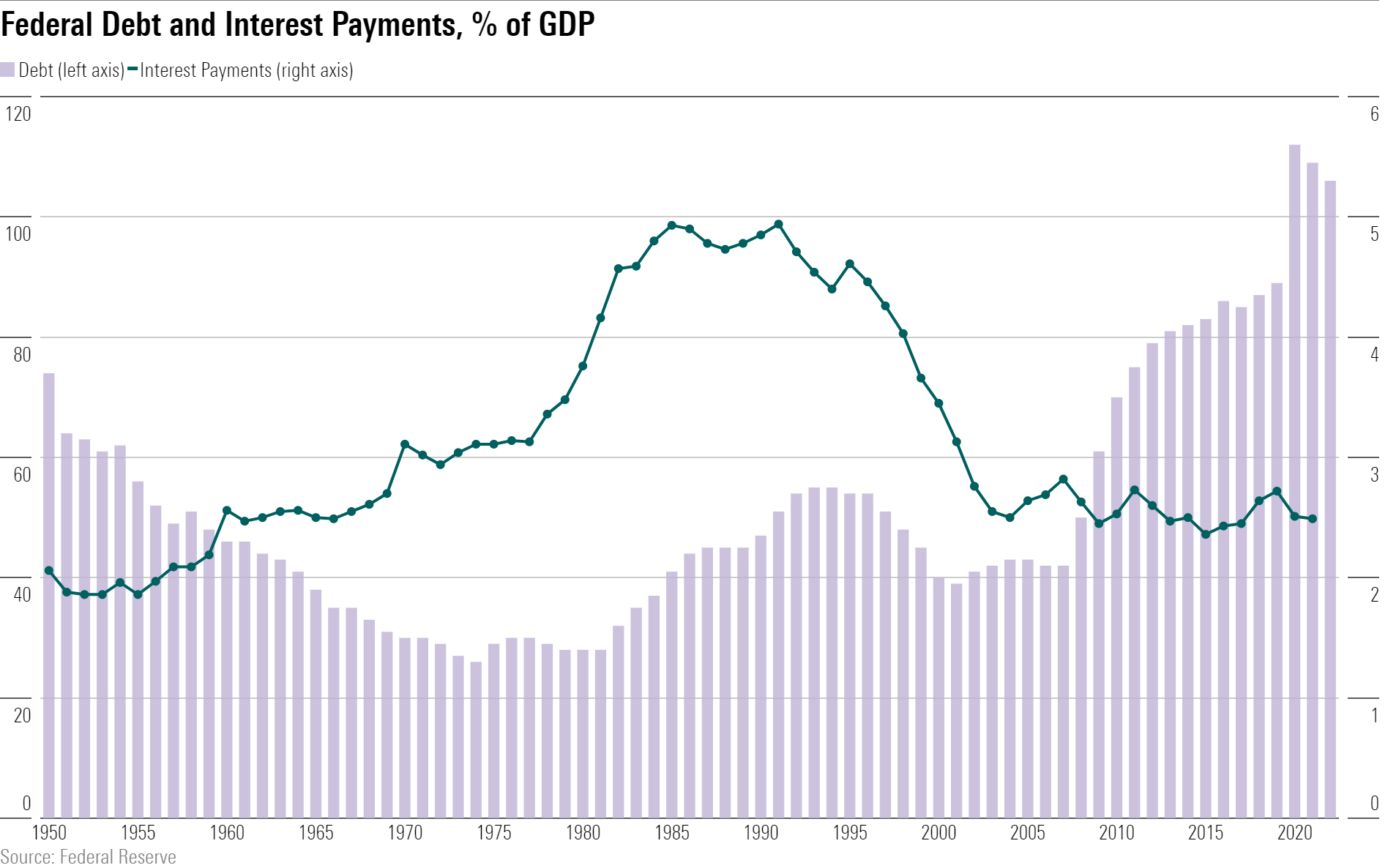

Even though the last two decades have seen the U.S. debt soar as a notable percentage point of GDP, the burden of that debt is quite light as gauged by interest payments. Thanks to a steep decline in interest rates, interest payments on national debt as a share of GDP are well below the peak reached in the 1980s. While interest rates have risen over the past year owing to monetary policy tightening, we expect rates to fall again as the Fed pivots to monetary policy easing following eventual victory over inflation.

However, if interest rates on government bonds jump higher because of a loss of confidence, the interest burden could become crippling. Paradoxically, by blocking the debt ceiling, the fiscal hawks in Congress could cause the very thing they hope to prevent: a collapse in the financial health of the U.S. government.

There’s no good way for investors to prepare for a doomsday scenario where markets lose confidence in U.S. Treasuries, other than being maximally diversified, including exposure to developed-markets investments other than the United States. Gold could also provide protection—gold prices surged by about 15% in the six months prior to Congress reaching an agreement on the debt ceiling in August 2011. But in general, a collapse in confidence in U.S. Treasuries is likely to lead to a widespread plummet in global asset prices and a severe global economic recession.

Fortunately, for now, we have every indication that this catastrophe remains a very remote possibility. But investors won’t be able to rest totally at ease until Congress finally deals with the debt ceiling.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/010b102c-b598-40b8-9642-c4f9552b403a.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_ffc6e675543a4913a5312be02f5c571a_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PKH6NPHLCRBR5DT2RWCY2VOCEQ.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/54RIEB5NTVG73FNGCTH6TGQMWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/010b102c-b598-40b8-9642-c4f9552b403a.jpg)