How Social Security Benefits Are Calculated and When to Claim

Morningstar contributor Mark Miller reviews ways to maximize Social Security benefits.

The following is an excerpt from Mark Miller’s new book, Retirement Reboot: Commonsense Financial Strategies for Getting Back on Track.

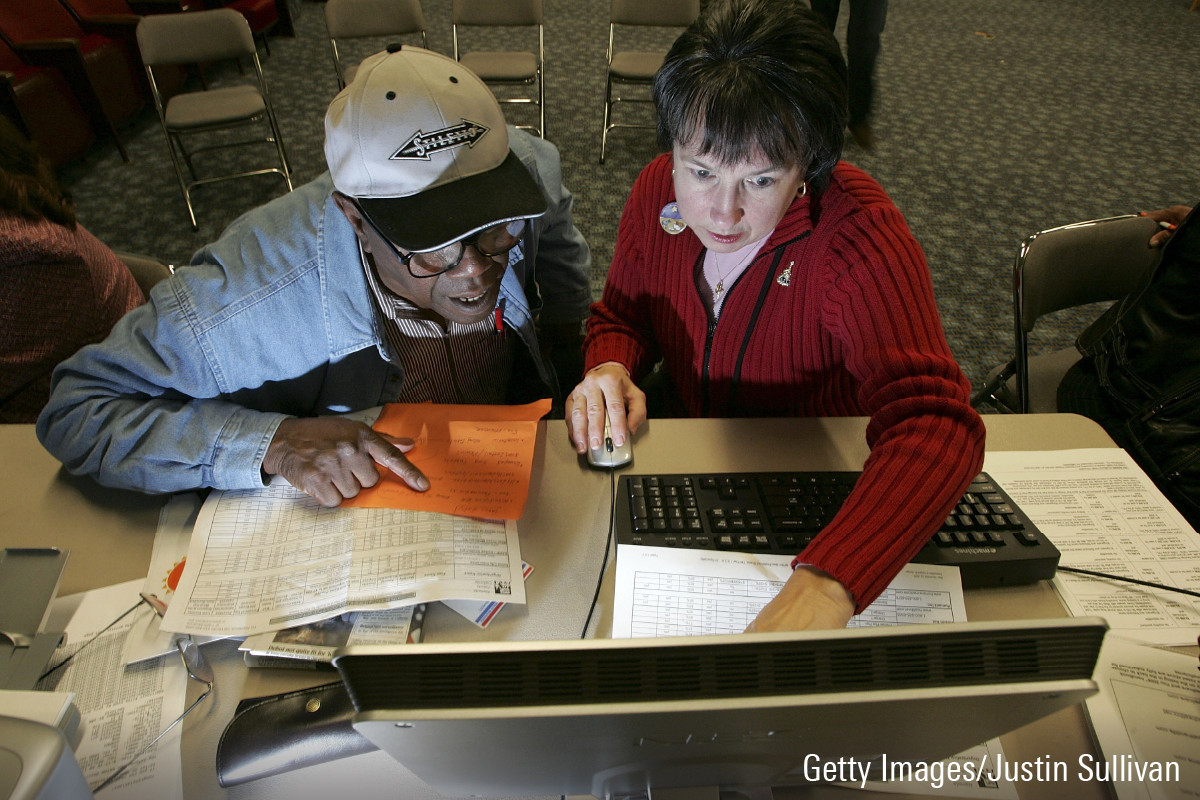

For most Americans, Social Security will be the single most important retirement benefit—full stop. With traditional defined benefit pensions waning, Social Security will be the only source of guaranteed lifetime income for most of us—and it’s adjusted for inflation as you go along the path of retirement. The program is especially important for women, who tend to outlive men but also earn less income and are more likely to take time out of the paid workforce to meet family caregiving responsibilities, generating lower levels of retirement assets. It also is critical for people of color and others who have faced disadvantages in the workplace. These workers are less likely to have jobs with retirement benefits, and they have lower earnings that leave them less able to save.

So it’s worth taking the time to understand how Social Security works—and decisions you can make that may boost your benefits substantially. In this chapter, you’ll learn how Social Security benefits are calculated, how to be smart about timing your claim to optimize benefits, how and when benefits are taxed, and how to get help with Social Security decisions.

Why Is Social Security So Valuable?

For most Americans, Social Security provides the only source of guaranteed lifetime income—the only other option is a defined benefit pension (see Chapter 12: Managing Your Pension) or an annuity purchased from an insurance company (see below). The certain nature of this benefit provides critical protection against longevity risk—that is, the risk that you will outlive your financial resources. Even relatively affluent retirees can exhaust their savings when they live to very advanced ages.

Unlike the complex decisions required when you save for retirement in a private account, your Social Security benefit amount builds automatically—Federal Insurance Contributions Act collections are made by you and your employers throughout your working years, and your benefit amount is determined by your wage history.

What’s more, Social Security’s benefit formula is progressive. That means it replaces a higher percentage of preretirement income for lower-wage earners than it does for high earners. This progressivity plays a powerful role helping to reduce wealth inequality across income and racial groups; one study found that in 2016, the typical Black household had 46% of the retirement wealth of the typical White household, while the typical Hispanic household had 49%. But the gap would be much larger if not for Social Security—Black households would have just 14% of the non–Social Security retirement wealth when compared to White households, and Hispanic households would have just 20%.

Social Security benefits are made more valuable by the annual cost-of-living adjustment, which aims to keep Social Security even with inflation as you move through retirement.

Social Security and Inflation

Social Security is the only component of our retirement income system built to provide risk-free, automatic inflation protection. Some defined benefit pension plans feature inflation protection, and you can buy it with long-term insurance policies. That’s about it.

Social Security benefits adjust annually to mirror consumer prices, and wage growth also factors into the benefit formula and the system’s finances.

Social Security awards an annual cost-of-living adjustment that aims to keep benefits even with inflation. The COLA is determined each fall by averaging together the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (or CPI-W) during the third quarter. Annual COLAs are applied to future benefit amounts starting in the year that you turn age 62, so even if you’re delaying your claim, future benefits will keep pace with inflation.

But it has not always been so. Congress enacted the automatic annual COLA in 1972, and it was first awarded in 1974 for the 1975 benefit year. Prior to that, adjustments were made by lawmakers in fits and starts—and generally in large amounts. For example, there was a 10% increase in 1971, a 20% increase in 1972, and two increases in 1974, totaling 18%.

Wage inflation also figures into Social Security benefit amounts, although the impact is smaller than the COLA.

Social Security benefits are determined by a worker’s history of wage income. Since AIME takes your highest 35 years of earnings and indexes them upward to the year when you turn 60, the formula reflects general wage growth in the economy over time. Think of it as a type of inflation adjustment, but one that uses wages, not consumer prices.

Will inflation-driven benefit increases destabilize Social Security at a time when the system already faces financial challenges?

Not really. Higher wages boost the amount of Federal Insurance Contributions Act revenue flowing into the system.

How Are Benefits Calculated?

Social Security benefits are determined by your history of wage income—you earn credits toward benefits automatically during your working years. After you claim benefits, monthly benefits start flowing, and they continue as long as you live.

In order to qualify to receive a retirement benefit, you must work long enough to become insured—one quarter of coverage for every year that has passed since age 22, and you need a total of 40 quarters of coverage to qualify (10 years of work).

Timing Your Claim

You can file for a retirement benefit as early as age 62, but most people will be better off by delaying their claim. For every month of delay, up to age 70, your monthly benefit increases to reflect the delay in claiming. That said, there can be very good reasons to claim early—for example, if you are in poor health and do not expect to have great longevity. And delaying your claim could be challenging if you need to fund living expenses while you delay by working longer or drawing down savings. That is not always possible.

The Social Security rules are designed to pay everyone roughly the same lifetime benefit, no matter when they decide to claim benefits, according to the life expectancy tables. So, if you claim at age 62 your monthly benefit will be considerably smaller than if you claim at age 66—but you’re likely to collect those benefits for a greater number of years. Conversely, a later claim will give you a higher monthly benefit—but for a shorter period of time.

If you claim before your FRA, your initial benefit will be reduced a certain amount for every month you claimed early. If you file 60 months before FRA, for example, your benefit is reduced by 30%—permanently. And if you delay your claim beyond FRA, you receive a delayed retirement credit, for every month of delay, up to age 70. For example, waiting one extra year beyond FRA gets you 108% of PIA—for life. Waiting a second year, until 68, gets you 116%.

Here’s a simple way of looking at this. A person with an FRA of 66 who claims at age 62 will receive a reduced benefit for the rest of his or her life—25% lower. Claiming at FRA is worth 33% more in monthly income than a claim at 62, and a claim at age 70 is worth 76% more. (Yes, you read that right: 76%.)

But the life expectancy tables are not the end of the story, because no one simply lives to these average figures. Some will beat those figures, and unfortunately, some of us will fall short of them. And this is where things get interesting.

Break-Even Analysis

One way to think about the claiming decision is the so-called break-even point—that is, the age when total lifetime benefits for someone who delays would be equal to what he or she would receive claiming earlier. Taking benefits early will pay you more—over the rest of your lifetime—if you don’t live to break-even. You also receive more if you delay benefits and then live beyond the break-even point. You receive less if you delay benefits and die before reaching the break-even age or claim benefits early and live beyond the break-even age.

I’m not a fan of break-even analysis. No one knows for certain how long they will live. Even if you’re in poor health as retirement approaches, an early benefit election may not be the better choice if you are married. Even more important, break-even analysis distorts the insurance purpose of Social Security, which is to replace monthly income when you grow old, become too disabled to work, or die leaving dependents.

As insurance, Social Security provides protection against what is called longevity risk. Most people don’t think of living a long time as a risk—but it is in financial terms. Even relatively affluent retirees can exhaust their savings when they live to very advanced ages—especially women, who tend to outlive men. For a widow in her 90s who has exhausted her savings, a maximized Social Security benefit with inflation protection is highly valuable.

If you do want to understand your break-even number, I recommend the description offered by Andy Landis, a Social Security expert and author. He expresses the idea of break even using a different term—money ahead. Andy keeps this analysis simple by excluding inflation, any possible taxation of benefits, or additional income from working longer, and any possible return on invested Social Security benefits. He assumes an FRA of 66 in all cases.

Under that analysis, if you file at age 62, your money-ahead age is 78. That is, you will be “ahead” until 78, when another person who waited until his or her FRA (66) catches up with you. From that point onward, that person is “ahead” for the rest of his or her life. If you file at 66, your money-ahead year is 82 1/2. After that age, someone who waits until age 70 to file is “ahead,” permanently.

How much further ahead depends on your longevity. Importantly, though, this analysis fails to look at the combined benefit of married couples. While one might be “ahead,” the couple likely will be behind.

Bottom line: it is prudent to delay claiming Social Security, if one is in an economic position to do so. Delaying protects you and your spouse against insufficient income in very old age when other assets are likely spent.

Reprinted with permission from Retirement Reboot: Commonsense Financial Strategies for Getting Back on Track by Mark Miller, Agate, January 2023.

Mark Miller is a freelance writer. The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-24-2024/t_a8760b3ac02f4548998bbc4870d54393_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)