What Will Happen to the Dollar in 2023?

A falling dollar could bring new risks for inflation, including rising commodity prices.

The greenback was golden for much of 2022, with the U.S. dollar riding its strongest wave higher in two decades on the back of rising interest rates.

But as the year draws to a close the tide seems to be turning against the dollar, and as investors look ahead to 2023, a weakening dollar could complicate the already uncertain outlook for inflation.

“We have to watch the dollar carefully,” says Lisa Shalett, chief investment officer at Morgan Stanley Wealth Management. “The dollar is in the process of peaking. If the dollar rolls over and rolls over hard, that is a problem for the Fed.”

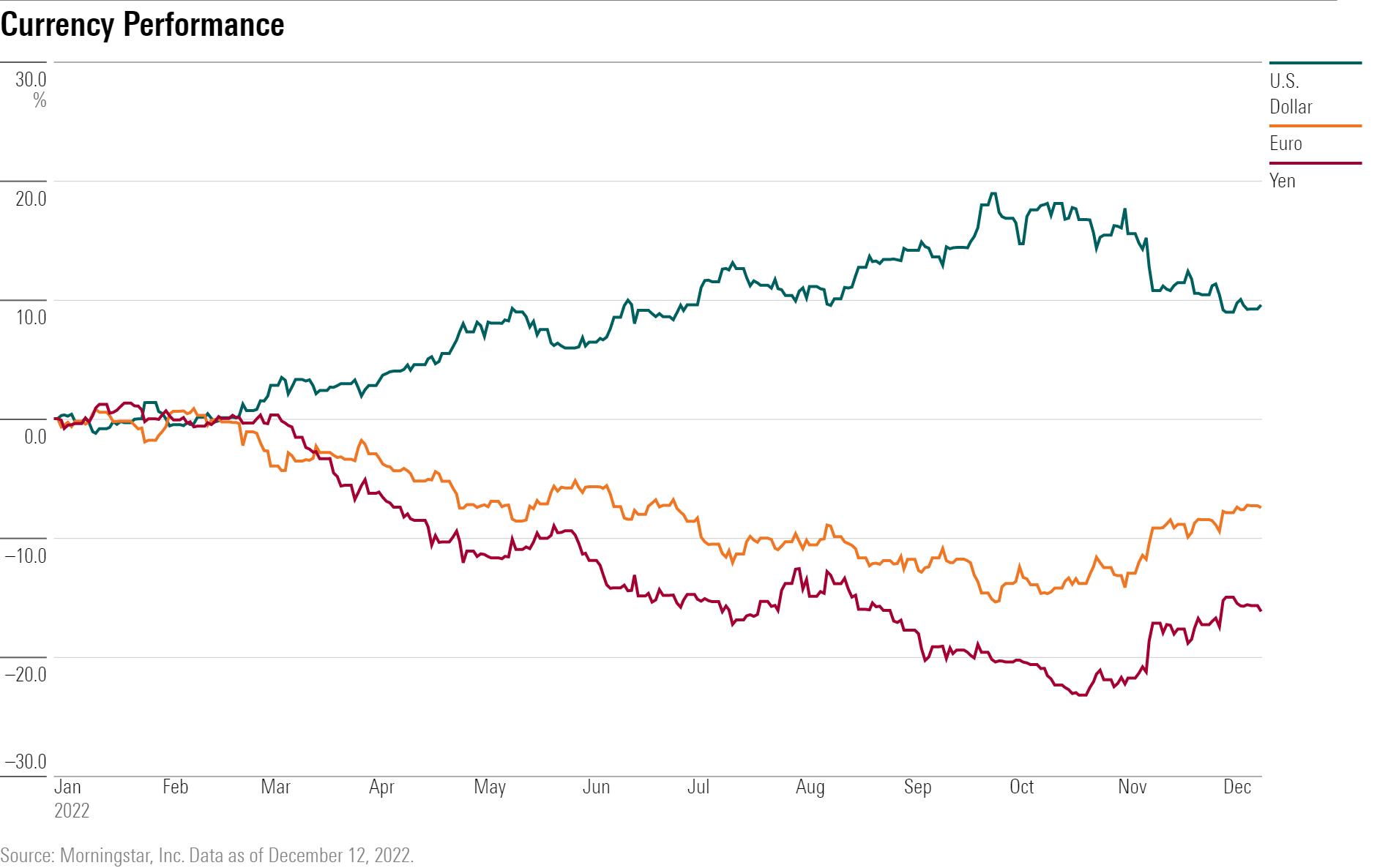

For much of 2022, it was a one-way ticket higher for the U.S. dollar against other major currencies.

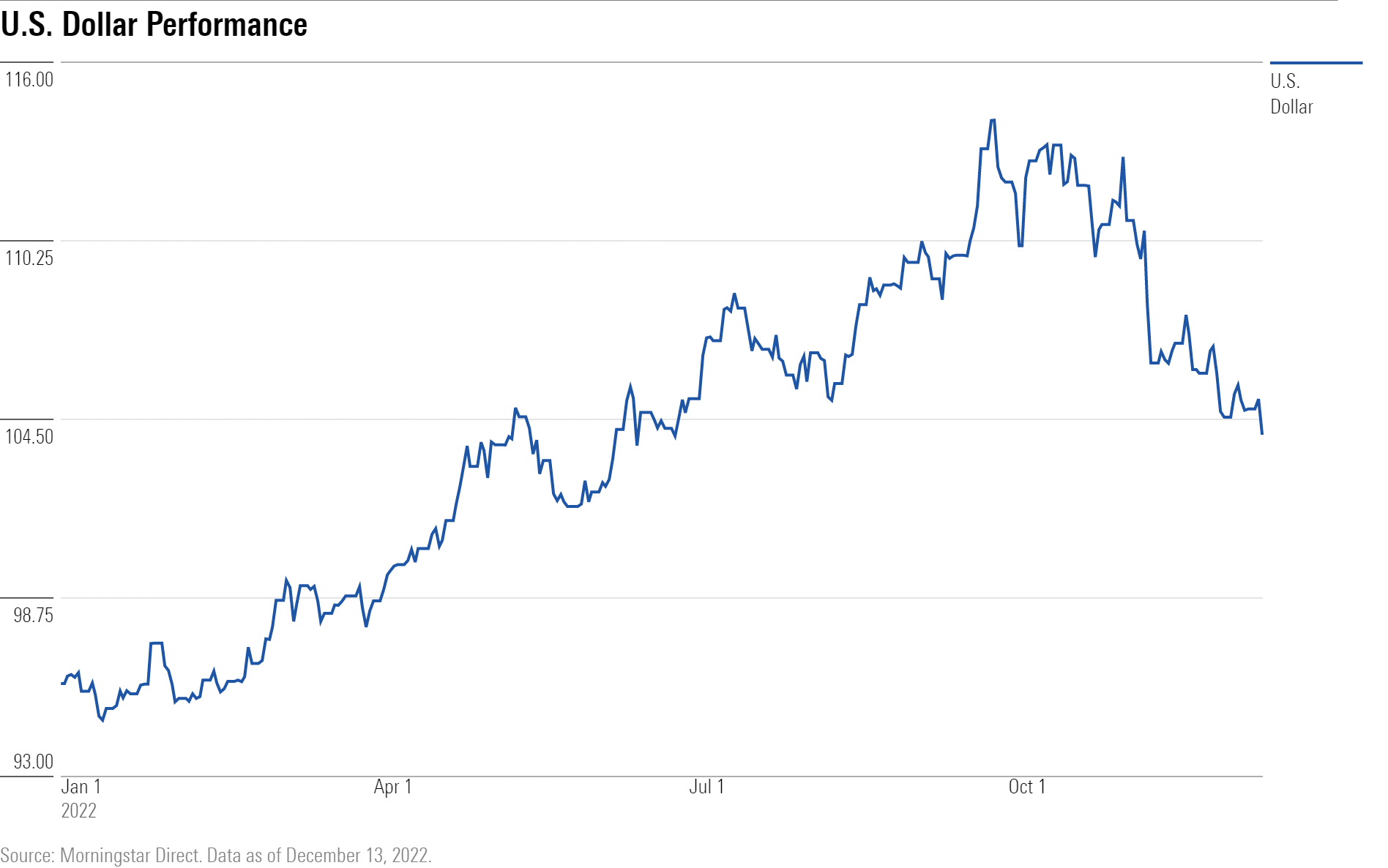

From its low in mid-January through its peak in September, the US Dollar Currency Index was up nearly 22% compared with double-digit declines in stocks and bonds.

In the past few months, however, the dollar has given back a chunk of its gains on signs that red-hot inflation was cooling and in anticipation that the Fed would slow the pace of rate hikes.

The dollar index, which measures the dollar against a basket of major currencies, has dropped nearly 9% since hitting a 52-week high of 114.78 at the end of the third quarter to a recent close of 104. It is still up more than 8% year-to-date compared with a loss of more than 17.5% in the Morningstar US Market Index.

Why Did the Dollar Rise in 2022?

Fueling the dollar’s rally was the fastest and most aggressive series of rate hikes by the Fed in 40 years. The currency, whose moves are closely tied to the direction of interest rates, soared as foreign investors looking for higher yields and a safe haven turned to U.S. Treasuries and the world’s reserve currency following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

The surging dollar, however, sent other world currencies tumbling, including the euro, Japanese yen, and British pound.

The dynamic helped accelerate already rising inflation abroad and forced other countries to defend their currencies through rate hikes and the sales of foreign reserves to buy back their own currencies. Dollar strength has also made it more costly for developing nations to service dollar-denominated debt. Big U.S.-based multinational companies saw their sales and profits thumped by currency impacts. J.P. Morgan Wealth Management estimates the strong dollar reduced third-quarter corporate revenue growth by 4%. And investors lured by better valuations in overseas stocks and the promise of better returns saw their investments pummeled this year unless they hedged against the dollar.

“Investors can congratulate themselves on spotting outperforming stock markets around the world, but they still underperformed the U.S. market in dollar terms,” notes Scott Opsal, director of research and equities at the Leuthold Group.

What Could Weaken the Dollar in 2023?

The swift and sharp decline in recent weeks has caught the attention of market watchers who are wondering how low the dollar can go and what that could mean for investors.

The primary catalyst behind the dollar’s turn lower has been changing expectations around Fed policy in response to evidence that inflation has peaked. That’s led to a belief among investors that the Fed will pause its interest rate increases before the second quarter, and begin lowering rates by the end of 2023.

In November, following a more benign-than-expected inflation report, the dollar recorded the biggest two-day drop since March 2009 and for the month recorded its worst-monthly performance in 12 years. A big factor in the improving inflation reports has been falling energy costs in the past six months.

Cooling inflation is only one catalyst leading to dollar weakness. The other driver would be improving expectations for growth outside the U.S. particularly in China and Europe, according to a brief by J.P. Morgan Wealth Management.

China is a particular focus, as the country’s leadership inches toward lifting harsh restrictions related to its zero-COVID policy of the past two years. The Chinese yuan has strengthened on optimism surrounding the relaxation of its pandemic rules.

Investors recall the huge economic boom that occurred as the U.S. emerged from lockdowns and imagine a similar expansion when China, the world’s second-largest economy behind the U.S., reopens.

“Look what happened to the U.S. in 2020 following the lockdowns,” says Phil Orlando, chief equity market strategist at Federated Hermes. “In the second quarter of 2020, U.S. GDP [gross domestic product] fell 29% quarter over quarter. In the third quarter, GDP grew 33%. It was the greatest economic boom in history.”

Adds Opsal of Leuthold: “The China reopening is underappreciated. It would lead to a significant shift in economic activity.”

In contrast, the Fed now sees the U.S. economy barely growing next year, projecting a gain in GDP of 0.50%.

Acknowledging that it’s not made enough progress in bringing inflation down, the Fed lifted its federal-funds rate this week by 0.50% to 4.25% and put its projected end point at about 5.1% by the end of next year. Fed Chair Jerome Powell said there are no rate cuts projected in 2023. The Fed, he said, remains resolved to continue to raise rates until there are clear signs that the path to its 2% inflation target is sustainable.

That’s reignited fears that the Fed might push the economy into recession, a likely negative for the dollar.

Other central banks are signaling that inflation may have peaked. The European Central Bank raised rates Thursday by a smaller-than-expected 0.50% to 2%, but said it would need to raise rates “significantly” higher, and at a steady pace to reduce double-digit inflation. It sees inflation running above its 2% target until 2025. The ECB also said it would reduce the size of its balance sheet by $15.9 billion per month on average until the second quarter of 2023.

The Bank of England also boosted rates Thursday by 0.50%, shifting down from its previous 0.75% hike as inflation fell to 10.7% in November from a 41-year high in October. The BOE expects inflation to continue to fall through the first quarter of 2023, although it remains well above its 2% target.

There are enough uncertainties in global economic outlooks that a dollar decline in 2023 is not preordained.

With elevated risks of recession looming in the U.S. and abroad, especially in Europe where inflation is running at double-digit rates and energy shortages are looming, it’s too soon to begin “waving the flag for the dollar’s turn, but we are paying close attention,” wrote the team at J.P. Morgan Wealth Management, noting that for now they prefer U.S. assets versus international.

The shift in sentiment on the outlook for the dollar can be seen in the action of two funds designed to track bullish and bearish bets on dollar futures contracts: The Invesco DB US Dollar Index Bullish Fund (UUP) and the Invesco DB US Dollar Index Bearish Fund (UDN). Bearish bets are climbing.

What Are the Impacts of a Weaker Dollar?

One potential problem that a weaker dollar poses to the Fed, Shalett says, is higher commodity prices.

Commodities are priced in dollars and the two asset classes move in inverse directions to each other: A strong dollar leads to weaker commodity prices and a weaker dollar results in higher commodity prices. At the same time, a weaker dollar gives a lift to other currencies, making commodities more affordable for those countries, increasing demand, and helping to lift global growth.

This dynamic could drive inflation higher at the same time the central bank is beginning to slow the pace of rate hikes based on lower inflation readings.

“If the dollar weakens materially and commodity prices go up, it could reignite inflation,” says Orlando.

The Negative Effects From a Weak Dollar

Not only does a weaker dollar lead to higher commodity prices, it also drives up the prices of imported goods, which adds to pressures on consumer spending and could lead to higher wage demands. That overseas trip you were planning suddenly gets more expensive as overseas currencies rebound and the costs of foreign services and products become more expensive.

At the same time, U.S. companies could see margins and earnings pressured as they have a harder time passing along price increases to customers.

Under a weaker dollar “foreign assets will do better,” says Opsal, and fixed-income assets will benefit. “It will be tough for the [U.S.] stock market.”

There are plusses, though. A weak dollar would be a boon for exporters. And U.S.-based multinational companies with far-flung overseas operations who suffered from the negative effects of currency translations this year would get relief. Also, investors interested in taking advantage of the bargains that international stocks represent, trading between 10 to 11 times earnings on average, compared with U.S. stocks, trading at about 18 times, are more likely to see their returns boosted from the positive currency translation.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T5MECJUE65CADONYJ7GARN2A3E.jpeg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_ffc6e675543a4913a5312be02f5c571a_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)