Why the Fed May ‘Yo-Yo’ With Interest Rates

Bank of America strategist sees multiple Fed pivots of raising and lowering rates.

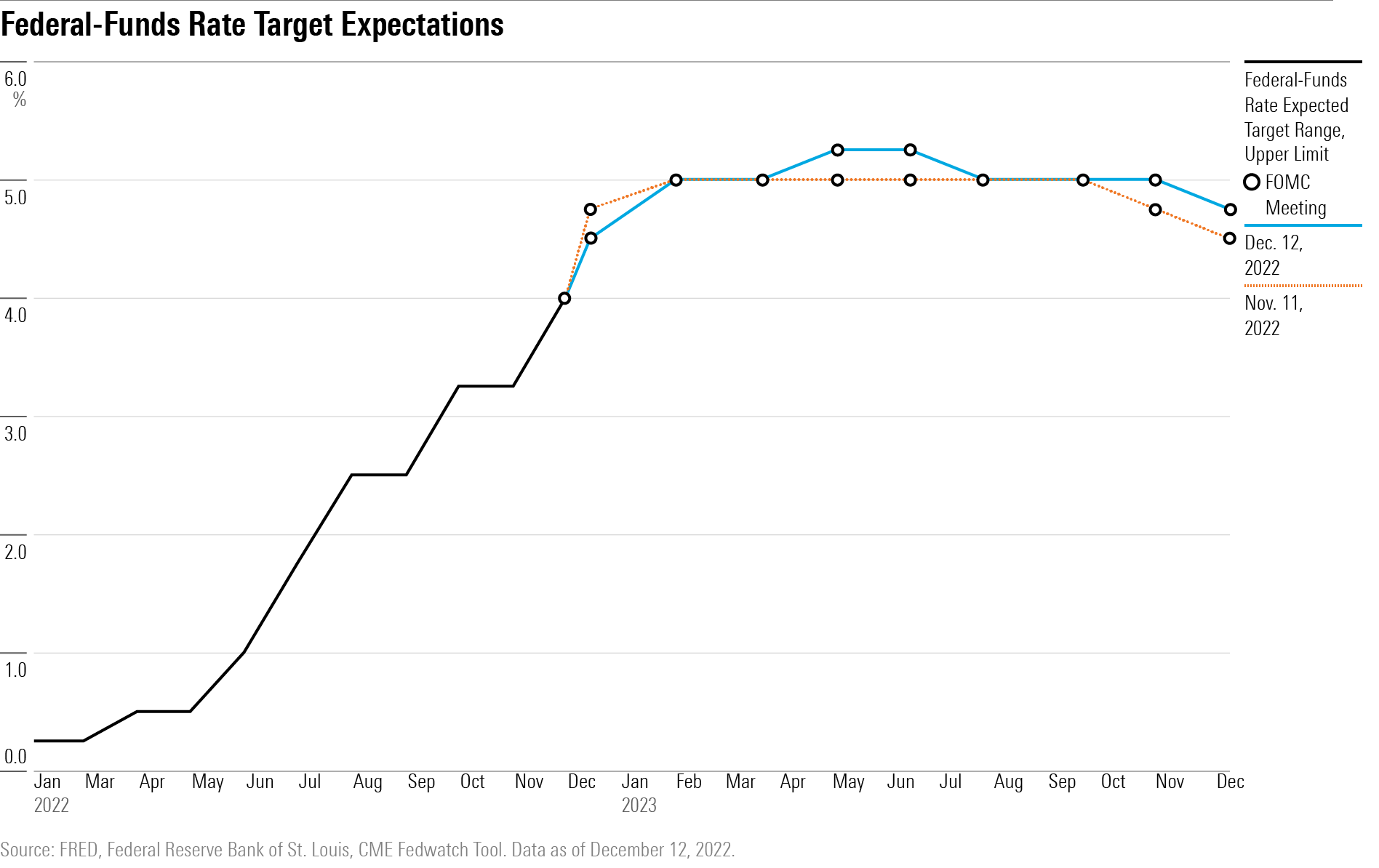

The Federal Reserve is expected to slow the pace of its interest-rate increases this week, but for many in the markets the focus is on what happens next year: When will there be a pause in rate hikes and when will there be a “pivot” to lowering them?

For now, most in the market expect the Fed to stop raising rates by the second quarter. From there, the Fed is seen cutting rates by the end of 2023 and staying on a course for easier money.

But Ralph Axel, longtime interest-rate strategist at Bank of America, says it may not be so simple as one and done.

“I think it’s likely we have multiple pivots,” Axel says, where the Fed lowers rates to keep the economy out of a recession, but in the process, allows inflation to bubble back up, necessitating a sooner switch back to tightening again than the markets are expecting.

“We think markets have become too complacent about how simple the trajectory of the Fed, and therefore of markets, will be,” Axel says. “The current market view is that it’s a single battle and once victory is declared, the game is over.”

Fed to Raise Rates Again in December

For now, tightening is still the name of the game.

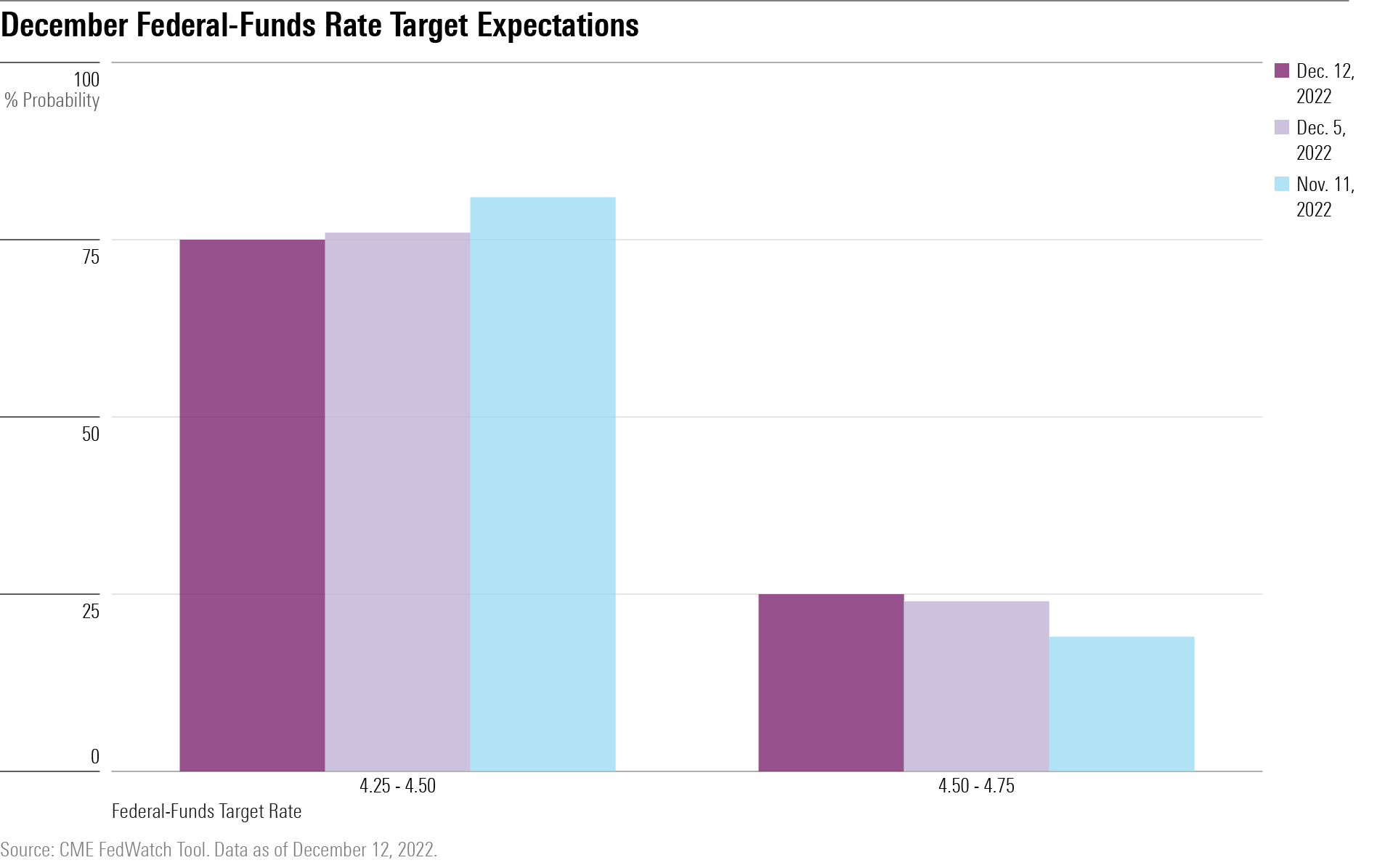

Market watchers widely believe that the Fed will lift the federal-funds rate Wednesday by 0.50 percentage points to a 4.25%-4.50% target range from the current 3.75%-4.00% range.

That’s a downshift from the unprecedented four consecutive 0.75-percentage-point hikes at the past four meetings. Fed Chair Jerome Powell signaled as much in a recent speech at the Brookings Institution, saying “the time for moderating the pace of rate increases may come as soon as the December meeting.”

When Will the Fed Stop Raising Rates?

It’s expected that the Fed will keep raising rates in early 2023. But markets are looking for a pause at around 5%.

Bank of America expects the Fed will stop its current round of interest-rate increases when the target rate hits 5.0%-5.25%, although if inflation stays hot and the economy strong, that could lead the Fed to move still higher before ending rate hikes.

Yet, bond markets are pricing in expectations that once the Fed stops raising rates the next move will be to lower rates, and to keep lowering them.

Axel cautions that may not be the case.

He says history suggests that the Fed will find itself in a “yo-yo” pattern of easing and raising as it becomes increasingly clear that inflation “doesn’t go away quickly,” especially amid a labor market that is stubbornly strong, an ongoing war, and the lingering public health threat of the COVID-19 virus and its effects.

“Inflation becomes a psychological issue,” says Axel. “It goes on for a long time and becomes ingrained. We’ve had one and a half years of high inflation since core CPI hit 5.4% in July 2021.”

Dovish at Its Core

There’s a psychological component to the Fed, too, that gets overlooked, he says. No matter its public pronouncements that it will stay the course until it gets the job done, and its dual mandate to maintain price stability and maximum employment, the Fed as a government agency is at its core “dovish” because “at the end of the day they want to help,” Axel says.

The Fed’s mandate “gets difficult when you get into a more painful window” in which heavy job losses and higher prices hurt consumers, he notes, recalling the massive protests and death threats against the Fed staff during the double-digit inflation of the late 1970s and early 1980s under then-Chair Paul Volcker.

For now, Powell is still talking a hawkish game, saying in November that “it is likely that restoring price stability will require holding policy at a restrictive level for some time. History cautions strongly against prematurely loosening policy.”

There’s no doubt that Powell is acutely aware of history. But it’s unclear he can escape it, Axel says.

If we are on the verge of a serious slowdown and there is a period of significant job losses, the Fed might find itself pressured to ease. It could justify such a move by concluding “we can always tighten later.”

The Fed, Axel argues, has already demonstrated its dovish tendencies by taking too long to move away from the easy-money policies adopted during the pandemic, and moving too slowly to a restrictive stance with inflation still running hot.

That highlights another big unknown: What exactly is the rate that would be deemed “sufficiently restrictive” to bring about price stability? Axel notes that San Francisco Fed president Mary Daly maintains financial markets are behaving as if the funds rate is 6%, well above the actual rate, suggesting we are already at or approaching the restrictive rate. Yet, Powell in his most recent speech suggested that rates, while higher, are not historically high and are back to where they were before the global financial crisis.

That could set the stage for history repeating itself, says Axel.

“Because of the lack of understanding of what rate level is required, it will be easy to think restrictive levels are attained when data cools for a period,” he says. “And this may set the stage for the Fed to potentially make mistakes similar to its last big inflation fight.”

As a result, investors should expect the Fed to remain active for longer, and that will mean the capital markets will continue to remain in its thrall as has been the case all year with stocks, bonds, and the dollar moving in lockstep.

“While the Fed is active all asset classes will move together,” says Axel. He cautions that “it’s unlikely that the Fed will become inactive as of March.”

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T5MECJUE65CADONYJ7GARN2A3E.jpeg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_ffc6e675543a4913a5312be02f5c571a_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)