When It Comes to Risk, It’s Dangerous to Trust Your Instincts

How to weigh risk tolerance against risk perception in market downturns.

As Mike Tyson famously said, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” But is it prudent to revise one’s investment strategy while in the throes of a financial mouth punch?

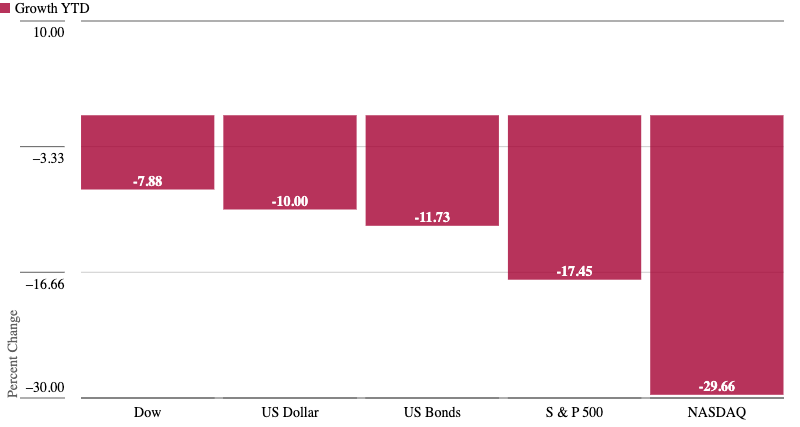

At the time of this writing, the Dow Jones Industrial Average is down 7.88% from the start of the year. The S&P 500 is down 17.45%, and the Nasdaq composite is down 29.66%. Bonds have fared poorly, too. Fidelity US Bond Index FXNAX, which earns a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Gold, has dropped by more than 11% from the start of the year. Even cash has lost significant value. The dollar has lost about 10% of its domestic buying power since this time last year.

In times like this, it’s easy to question one’s long-term investment strategy. Hindsight bias would have us believe that we saw this coming and should therefore trust our gut about what comes next. Looking forward from this new vantage point, the future may look riskier than it did when initially setting an investment course, and a change may seem like the prudent move. We may tell ourselves that when we first set out, we made some broad assumptions, but now we have more information and therefore can better judge what’s on the horizon.

Here, I’ll explain why it’s dangerous to trust our instincts when it comes to risk, and what we can do instead.

Weigh Your Risk Tolerance Against Risk Perception

First, we need some definitions. There is a meaningful difference between a person’s risk tolerance and their risk perception, and both are relevant to the discussion.

Risk tolerance is a person’s general attitude toward risk/reward trade-offs. It refers to the amount of risk a person is willing to take on for a particular reward. A person with a very low risk tolerance will not want to risk losses, even if the gains could be substantial. A person with a higher tolerance for risk will be willing to experience losses in pursuit of sizable enough gains. A person establishes their risk tolerance using what is commonly referred to as System 2 thinking. System 2 is characterized by slow, deliberate thought that is largely devoid of emotional influence.

A person’s risk tolerance can be thought of as the set of preferences that one has about how much risk they are willing to take under different trade-off conditions.

Attitudes toward risk/reward trade-offs vary by individual, but a person’s risk tolerance has been shown to remain consistentover time.

Risk perception refers to how risky a specific action feels to an individual. Risk perception is an in-the-moment estimation of the riskiness of an action or event, and thus it can be affected by emotion, culture, past performance, and even nuances of information like wording, color, and graphics.

Taken together, these two ways of thinking about risk create the opportunity for misjudgment because an investment that was perceived to be safe one day could appear very unsafe the next, depending on the internal state of the person making the judgment. That means an investment that aligned well with a person’s risk tolerance on Monday could feel far too risky on Tuesday. In this case, it wasn’t their risk tolerance that changed but rather their assessment of the riskiness of the investment itself.

The resulting misalignment creates a state of internal disequilibrium, discomfort, and disquiet for most investors at least some of the time.

Cope With Investment Discomfort

There are two main approaches to coping with internal discomfort: action-oriented coping and emotion-oriented coping.

Action-oriented copers tackle the cause of the problem, and emotional copers work to assuage the effects. Each of the two approaches can be either helpful or harmful, depending on the circumstance. For example, if a thorn in your hand is causing you pain, it’s best to remove the thorn. However, if the pain is coming from stitches, it’s better to ignore or dull the discomfort until it passes.

When it comes to investment discomfort, we need to be careful and clear-eyed about the cause so that we can respond properly. In the case of risk assessment, we need to ask, “What specific information triggered the change in my judgment?” If the shift stemmed from fundamental changes in underlying investment valuation factors (think changes in executive management, mergers and acquisitions, lawsuits, and so on), then it may indeed be time to reassess the risk level of the investment and determine whether it still belongs in your portfolio. In that case, an action-oriented response may be appropriate.

However, if the fundamentals of the investment haven’t changed, but your feelings about its riskiness have, then before jumping into action, consider the ways that context and circumstance might be skewing your view.

- Recent performance.—Given the same fundamentals, investments that performed well in the recent past may feel less risky than those that performed poorly in the recent past. Investors experiencing losses (pretty much all of us right now) are vulnerable to misjudgment.

- Fear itself.—Fear is the mind-killer. Even if it’s in a different domain of a person’s life, fear can skew a person’s judgment of risk. “So-and-so-on-TV thinks a recession is coming,” probably isn’t reason enough to ditch your plan. Warren Buffett has lived through 14 recessions so far. Fear makes investors vulnerable to misjudgment.

- Context clues.—The information we consume is often packaged within a larger context. A news channel, a sales website, and a shock jock podcast may all present the same information in very different ways. The presentation of information affects our perception, and so we need to be savvy consumers of data and analysis. Sensationalism and emotional messaging make investors vulnerable to misjudgment.

Unskew Your View

When emotions run hot, distance can help. I’ve written before about psychological distance, and it’s a concept I think every financial decision-maker should become familiar with. When we are too close to a situation, or too emotionally involved, it becomes magnified in our mind’s eye, and we can overestimate the importance, value, or urgency of the issue at hand. Conversely, when we hold things at a distance, they lose some of their emotional potency. It’s easier said than done, but keeping a healthy distance from sensationalist headlines and making the mental effort to see emotionally charged information from a high-level, long-term perspective can help you keep your head while all around you are losing theirs.

Reframing information can also help. When we consider a trade-off, we are comparing an action or outcome with some alternative. Choose the target of comparison carefully. Your portfolio is down 15%? Compared with what? Yesterday? Last year? A relevant benchmark? I was feeling pretty gloomy about my own portfolio until I compared it with a market index. In comparison with the general market, I could see clearly how my diversification strategy has protected me and served me well this year. A reframe from absolute losses to relative ones then resulted in an emotional shift—from pain to gratitude.

Chances are that when you set your investment course, you weren’t planning on smooth sailing every day. What matters is not the short-term ups and downs, but that you are on track to reach your long-term goals. Make sure your frame of reference is one that favors a long-term, goal-focused strategy.

Remember the Long Game

The difference between risk tolerance and risk perception is more than semantics. Risk tolerance is a general attitude toward risk/reward trade-offs, and each of us has a particular set of risk/reward preferences that stays fairly stable over time. It makes sense, then, to base our long-term investment strategies on stable preferences like risk tolerance.

However, long-term investment plans are only useful if we can abide by them. The fact that our day-to-day perceptions of risk are so malleable and easily affected by things that are not related to the fundamental value of our investment holdings means that we need to be watchful of our own emotional and psychological state if we want to stay the course. There are times when plans do need to be altered, but not every instinct to change course should be heeded.

Fear, loss, and dramatic headlines can skew our judgments about risk. In these moments, an ounce of self-awareness can be worth a pound of self-discipline. Know your triggers and keep your eye on the fundamentals. Before you change your strategy, try changing your point of view.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/6c608d29-bb89-4580-943a-7819645ad538.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_1997613e43634249b59dd28db9b24893_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/Q7DQFQYMEZD7HIR6KC5R42XEDI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/5N6PBZJLMJEIXBH6EHTKPDK6NE.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/6c608d29-bb89-4580-943a-7819645ad538.jpg)