Are Growth Stocks Worth a Look in 2023?

The signs are promising.

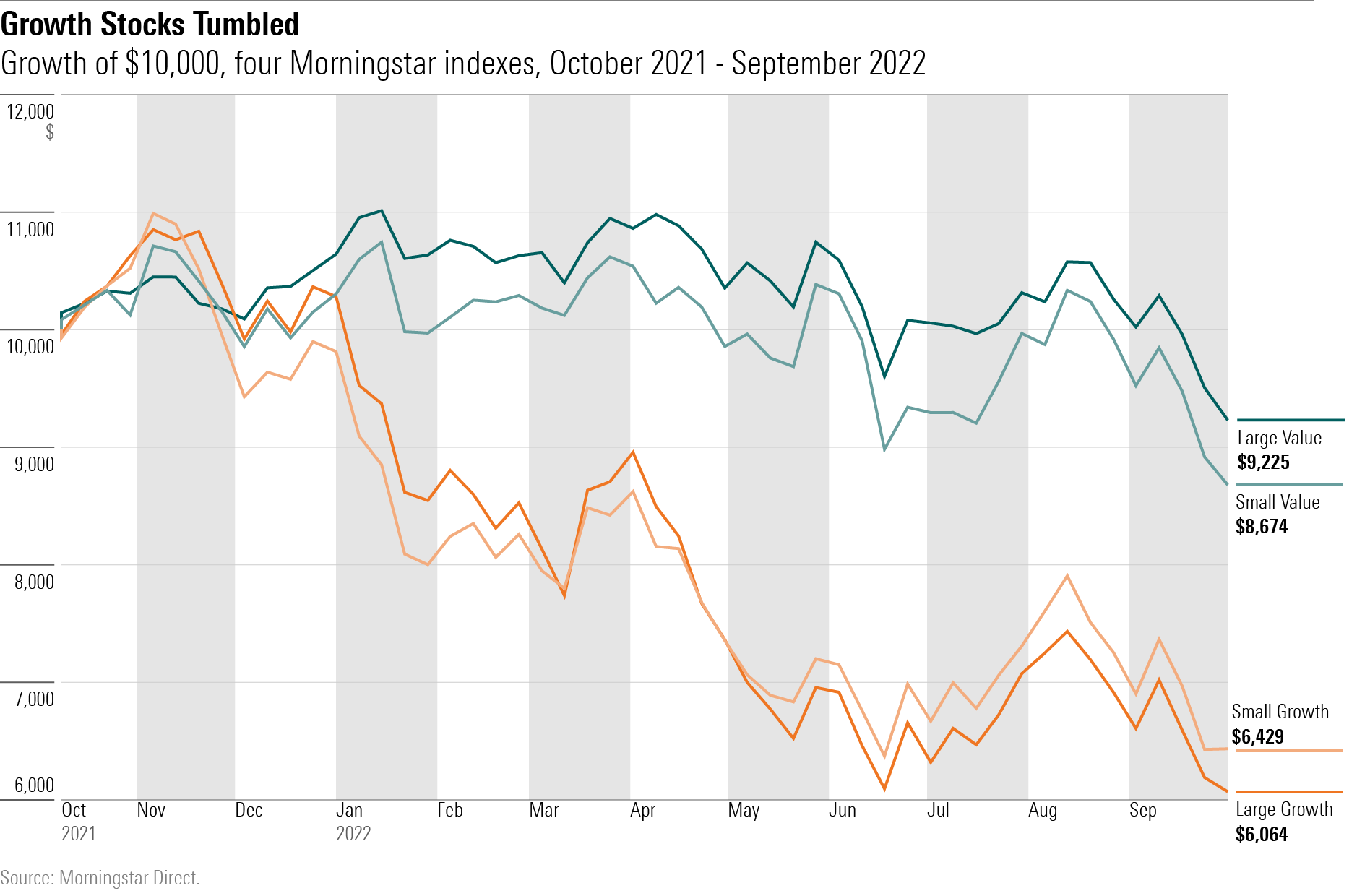

A Growth-Stock Pothole

After several years of spectacular gains, U.S. growth stocks abruptly reversed course in 2021. Small-growth companies peaked that January, while their large-growth counterparts remained strong for an additional several months. When autumn arrived, however, blue chips also succumbed. For the 12 months from October 2021 through September 2022, the two groups fell together, with small-growth stocks dropping 35.7% and their large-growth cousins 39.4%.

Meanwhile, value stocks mostly held their own. In contrast with growth stocks, the best value stocks were multinationals, rather than secondary issues. But the difference between larger and smaller companies was modest. As the following chart illustrates, returns during that 12-month period were determined more by investment style than by size. Relatively speaking, value was in, growth was out.

As Expected

This outcome was no great surprise. As 2022 began, Morningstar’s Dave Sekera wrote, “Although the [U.S. stock] market is broadly overvalued, we see upside opportunity for investors in the value category and small-cap stocks, both of which should benefit from continued economic prosperity.” True, value stocks have not advanced, but Sekera’s analysis pointed in right direction, and for the right reason: Because their businesses are typically weaker than growth stocks’, and are therefore more vulnerable to recession, value stocks tend to thrive when the economic tide rises.

Conditions have since changed. Since Sekera penned those words, inflation has stubbornly persisted despite widespread predictions by economists that it would abate. In response, the Federal Reserve has increased short-term interest rates by sixteenfold(!), from 0.25% in mid-March to today’s 4.00%. For that reason, The Conference Board, an economic research organization, now predicts that there is a 96% chance of a U.S. recession within the next 12 months.

Consequently, that January 2022 forecast no longer abides. The big news, of course, has been inflation’s intransigence. The United States had not suffered such an inflation shock for more than 40 years. However, inflation has not been directly the problem, because it alone does not strongly affect corporate profits. Once the initial shock of the price increases abates, companies are generally able to keep pace with spiraling costs by hiking their own prices.

Inflation’s Invisible Hand

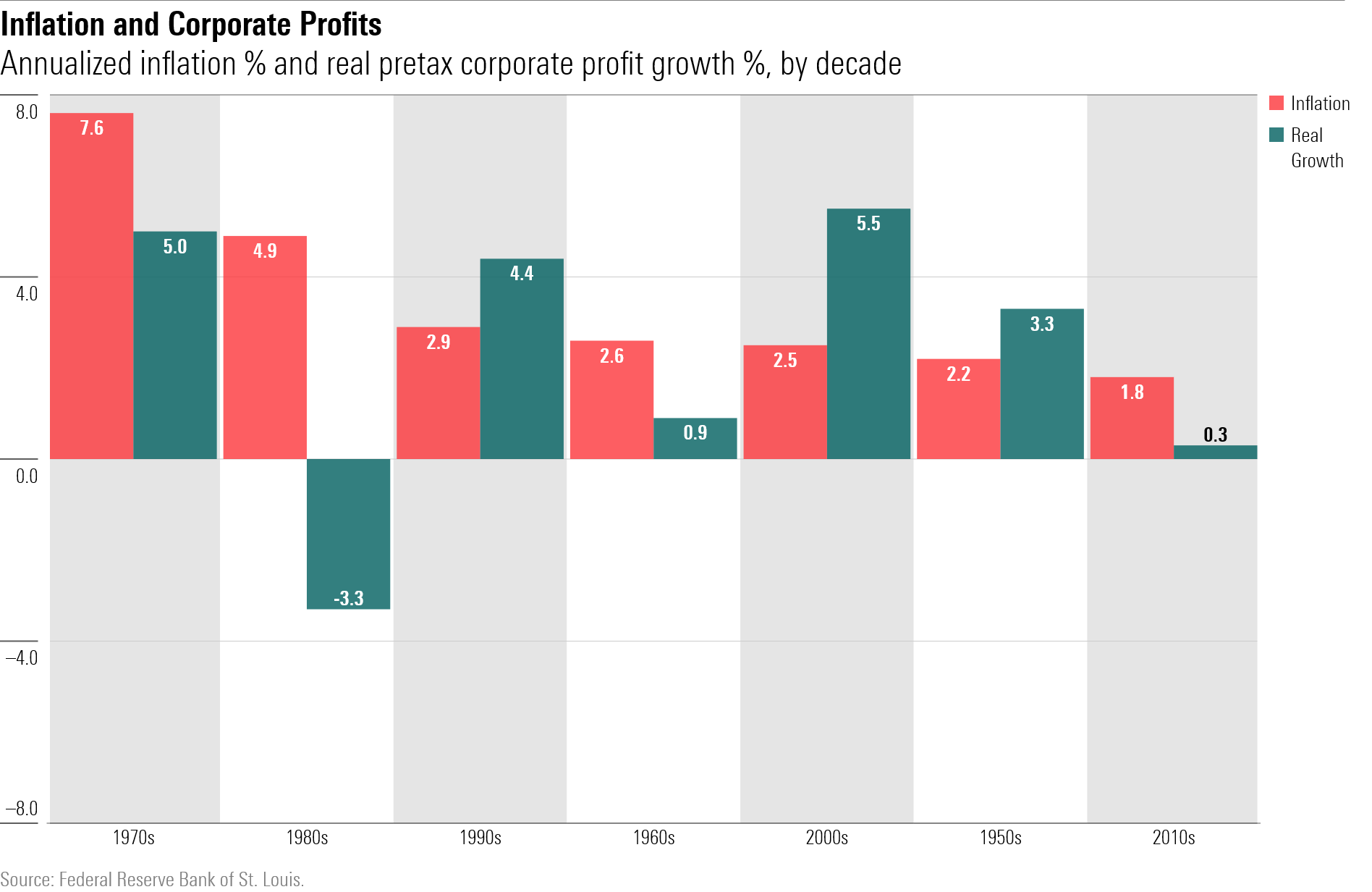

History provides the confirmation. For each of seven decades, from the 1950s through the 2010s, I calculated two numbers. One was the inflation rate, as measured by changes in the seasonally adjusted Consumer Price Index, and the other the growth rate of real U.S. corporate profits before taxes. (Both are average annualized figures.) If inflation hampers the ability of American companies to grow their profits, that power should appear in the numbers.

It has not. In the chart below, the seven decades are organized in order of their inflation rates, from highest on the far left to lowest on the far right. Thus, the 1970s endured the steepest price gains, at an annualized 7.6%, while this past decade was the quietest, at a modest 1.8%. Accompanying each inflation rate is a second bar, representing the real growth in pretax corporate profits.

Despite its sharp inflation, the ‘70s enjoyed the second-largest improvement in corporate profits. Meanwhile, the 2010s experienced both the lowest inflation and the second-weakest profit growth. (If you are speculating that the 2010s sputtered because the arrival of COVID-19 ruined the final year’s totals, well considered. However, that hypothesis fails, as I concluded that decade in December 2019.) In fact, those findings imply that inflation improves profits. But such was not the case; overall, the blue and orange bars bear no apparent relationship.

Ripple Effects

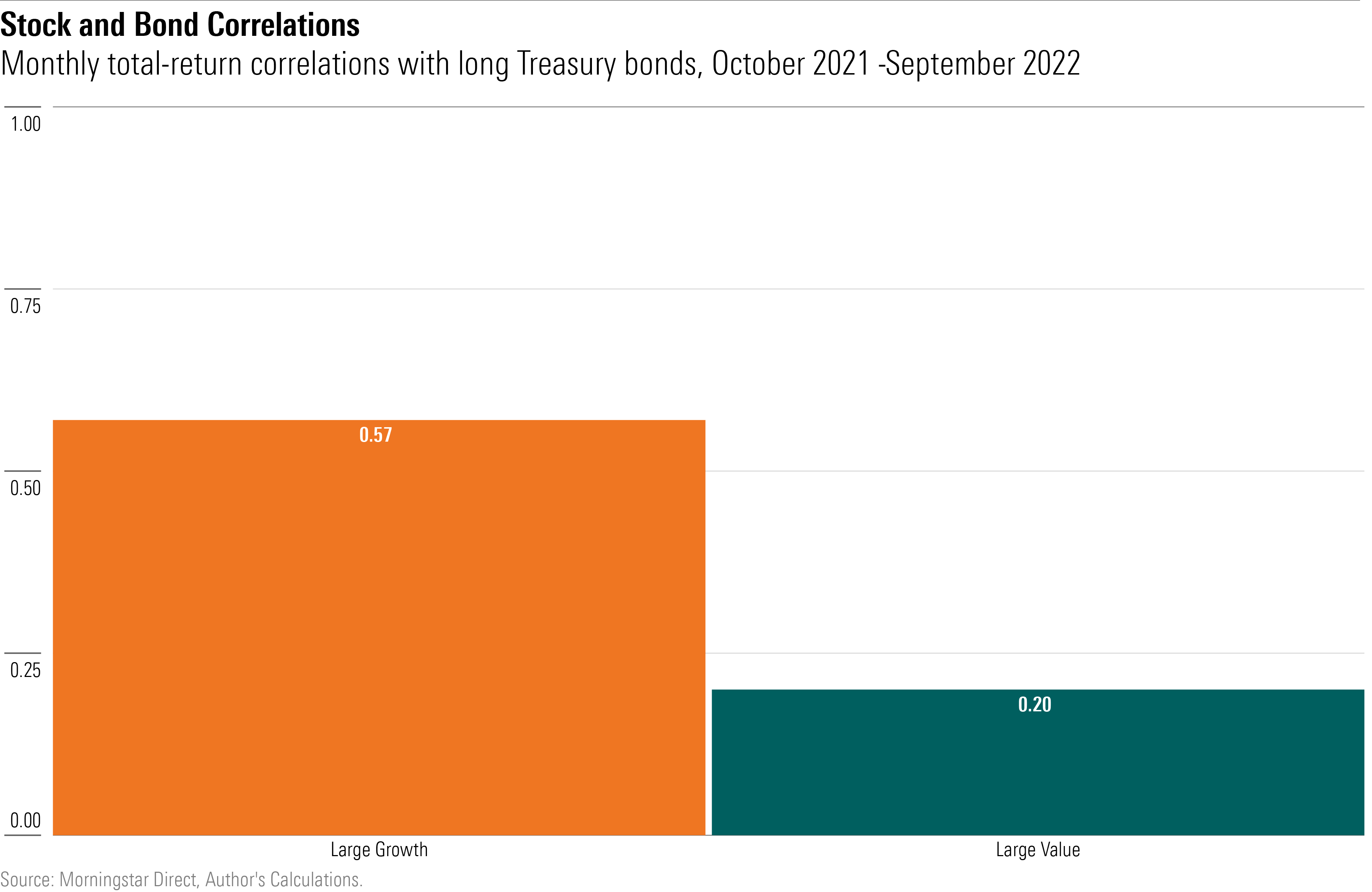

High inflation has two consequences, though, one of which hurts growth stocks and one of which helps them. We have previously observed the harmful influence: rising interest rates. Because the primary reason to own growth stocks is for earnings that occur well into the future, rather than for their current cash flows, growth stocks can to some extent be regarded as long bonds. They therefore are highly vulnerable to the interest-rate spikes that typically accompany inflationary surges.

(Cliff Asness of AQR recently disputed this claim, on two grounds. First, although in theory growth stocks have much longer durations than value stocks, in practice they do not, because growth companies don’t remain elite for very long. Their superior prospects are a mirage. Second, per AQR’s research, the connection between growth-stock performance and Treasury bond yields is tenuous.

The initial argument, I think, can readily be refuted. Reality is immaterial. If the marketplace erroneously believes that high-growth companies will remain so indefinitely, that is how such stocks will trade, even if the reality is otherwise. The second assertion is more compelling. The link between the behavior of growth stocks and that of the bond market is indeed inconsistent. Over the past year, though, it has been very much in evidence, as witnessed by the correlations between the monthly returns of growth stocks, value stocks, and long U.S. Treasury bonds.

Admittedly, that chart was created from only 12 data points, but the daily returns after either the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ CPI reports or Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s comments have followed a similar pattern.)

The other, more beneficial ripple effect has also been mentioned—the economy’s showing. If economic expansion (after a sluggish start, gross domestic product growth rebounded during the third quarter) boosts the relative fortunes of value stocks, then it stands to reason that contraction aids growth companies. Which, indeed, often occurs, as witnessed by their outstanding 2020 results. For growth stocks, less can very much be more.

Looking Forward

Of the three likeliest investment outcomes in 2023, two favor growth stocks:

1) Inflation has peaked, and the economy escapes recession.

Wouldn’t that be nice? If so, all equities will likely rally, but I suspect that growth stocks will perform best, retracing much of their lost ground as the Federal Reserve gradually lowers interest rates.

2) Inflation has peaked, and the economy goes into recession.

Less pleasant but relatively strong for growth stocks. They would benefit both from declining interest rates and from the strength of their business operations.

3) Inflation has not peaked, and the Federal Reserve continues to raise rates.

Oh, dear. This would be a problem for growth stocks, regardless of whether the U.S. suffers a recession.

Of course, these are but three scenarios. It’s quite possible that the economy fails to match any of those expectations. Nevertheless, as when entering 2022, the economic outlook does seem to offer some clues about what the next year might bring.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/LUIUEVKYO2PKAIBSSAUSBVZXHI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)