Why Investors Should Lower Expectations for Making Money on Stocks

Vanguard, others predict bonds will rival single-digit returns on stocks; best bets are overseas.

The era of big returns on stocks is over. It’s time for investors to recalibrate their expectations.

That’s what many Wall Street firms and advisors are telling their clients.

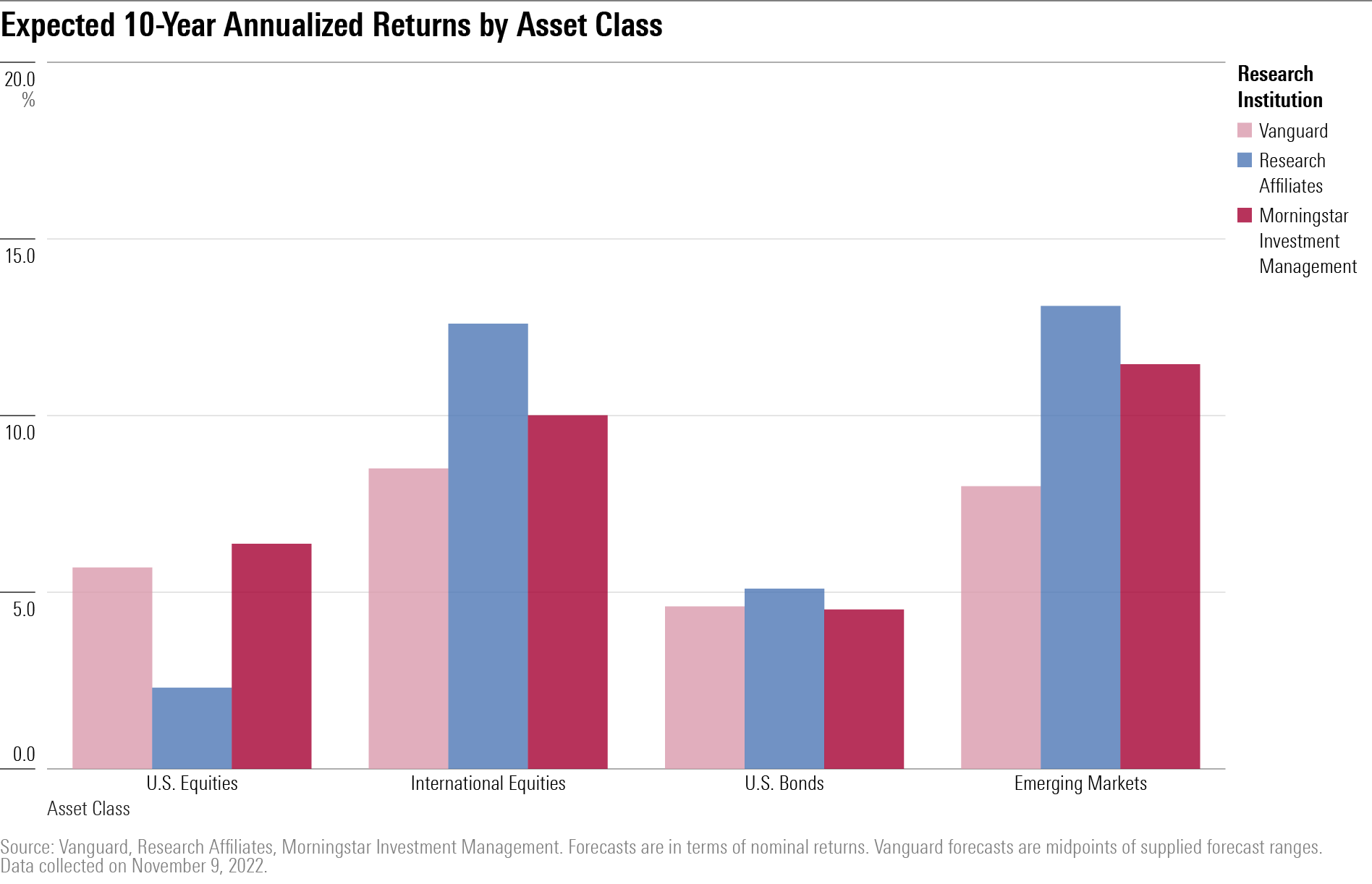

Look for lower returns from U.S. stocks during the next decade compared with what has historically been the case, and expect U.S. bond returns that are on a par with equities. The best returns are projected for overseas stocks and bonds. Returns from most asset classes are projected to be positive.

“The next 10 years will be different than the last 10 years,” says Jim Masturzo, partner and chief investment officer of multi-asset strategies at Newport Beach, California-based Research Affiliates. “It will be more normal.”

Expect Single-Digit U.S. Stock Returns

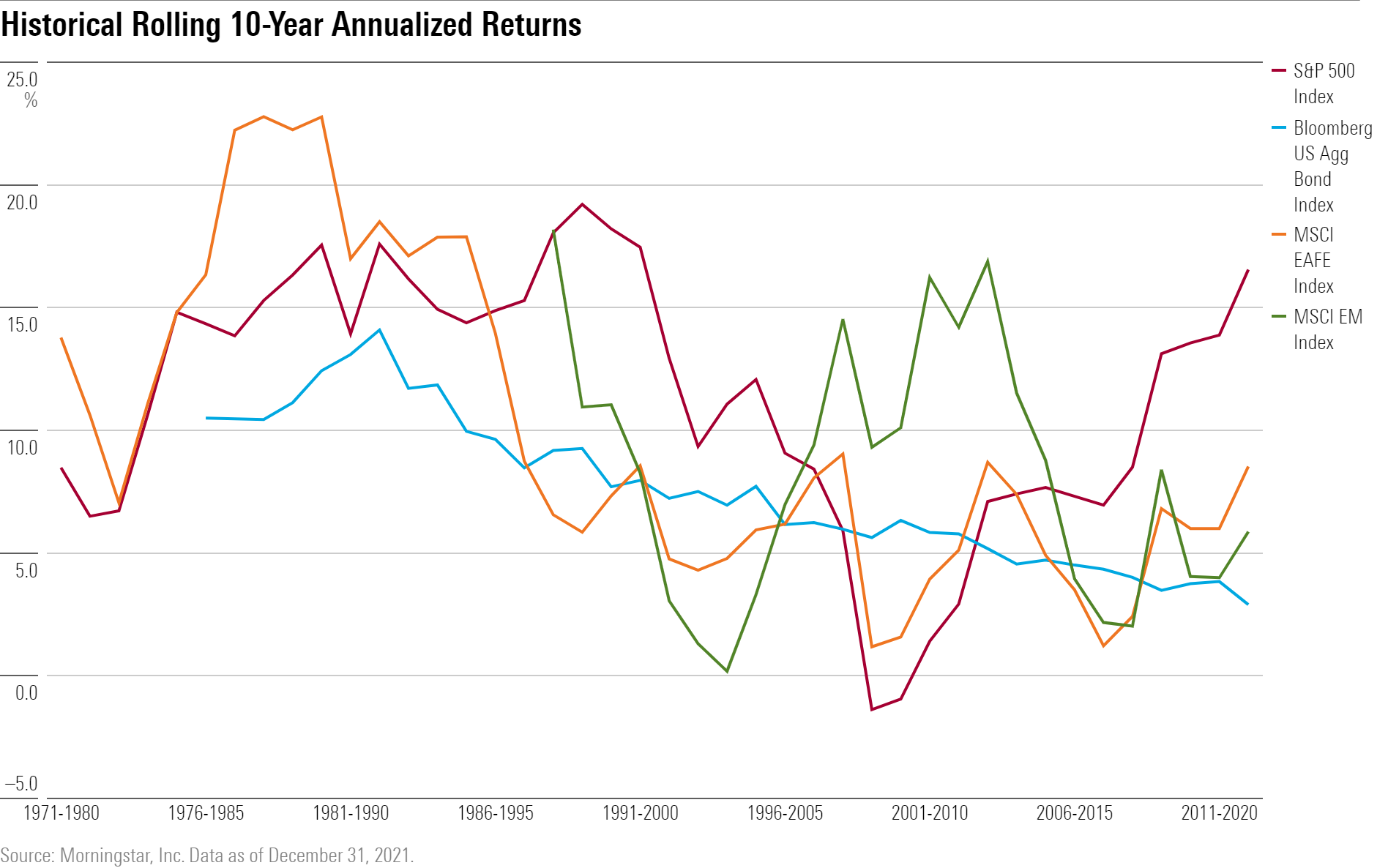

With inflation at the highest levels in 40 years, against a backdrop of rising interest rates and a decline in valuations, long-term returns for U.S. equities are projected to be in the low- to mid single-digit territory. That’s compared with a historical yearly average of 12%-13% before inflation, and well below the nearly 16% average annual returns of the past decade. This is clearly a whole new world to which investors are unaccustomed after decades of low inflation and the near-zero interest rates of the past 10 years.

“Returns will be more muted compared with history and especially the past two years, especially for equities,” says Roger Aliaga-Diaz, head of portfolio construction and chief Americas economist at The Vanguard Group.

Bond Returns to Rival Stocks

On the brighter side, bonds are seen giving equities a run for their money, as fixed-income returns are projected to rival those of stocks.

“Bond market returns could equal equity returns with less risk,” says Joseph Carson, economic consultant and former chief economist at AllianceBernstein. Returns on stocks in the next decade will appear “minuscule” at 4%-5%, he says, mainly because “equity returns for three of the last four decades were far above average.”

Stocks benefited from declining inflation and lower bond yields in the 1980s. Stable inflation and expectations of “a new era of long cycles of growth and earnings” pushed stock returns higher in the 1990s. And “in the decade ending 2020 it was zero rates and inflated market multiples” that led to outsize gains in stocks, says Carson.

The Lost Decade

The outlier decade proved to be 2000 through 2009, a period that included the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, as well as two punishing recessions and accompanying bear markets that dragged down returns and set the stage for easy money conditions. In what became known as the Lost Decade, stocks delivered a negative annualized total return of 0.95%, the only decade outside the Great Depression in which total returns for the period were negative.

At the start of the decade, a bubble in technology, telecommunications, and media stocks burst, resulting in a recession and the bear market of 2000-02, when stocks fell nearly 50%.

Not long afterward came the global financial crisis of 2007-09, precipitated by a housing meltdown brought about by banks and mortgage companies extending credit and making nontraditional interest-only and adjustable-rate loans to high-risk borrowers that were then packaged into mortgage-backed securities and collateralized debt obligations and sold as stable and safe investments.

With home prices skyrocketing, the Federal Reserve started raising rates to cool the market, which prompted a wave of mortgage defaults and a subsequent liquidity crisis. The result: the deepest and longest-lasting recession since World War II. Stocks fell about 55%. The unemployment rate more than doubled.

The interventions to rescue the financial system and the economy during the crisis introduced ultraloose monetary policies that were reintroduced more recently during the pandemic crisis of 2020, creating a boom in asset prices and driving inflation to the highest levels since the 1980s. Aiming to rein in spiraling prices, the Fed has boosted the federal-funds rate six times this year at an aggressive pace and plans to continue until it sees clear signs that inflation is abating and heading back to its target rate of 2% from more than 8%. That’s driven up yields on bonds, driving their prices lower, and sent stocks sliding.

No one expects inflation and interest rates to stay at current levels over the next 10 years, but they will be at higher levels than has been the case in the past decade. And that will affect valuations.

The Case for Bonds

“Definitely, the case for bonds in the portfolio is coming back,” says Aliaga-Diaz of Vanguard. “Higher yields make the case for bonds stronger.”

Over the next 10 years, Vanguard is forecasting annualized nominal returns, that is before adjusting for inflation, on U.S. equities of 4.7%-6.7% and U.S. bonds at 4.1%-5.1%. Research Affiliates projects annualized nominal returns on U.S. equities of 2.3% over the next decade. Its forecast for U.S. bonds is 5.1% on an annualized nominal basis. Morningstar Investment Management projects U.S. stocks will deliver 5.5% in annualized nominal returns and 4.8% for U.S. bonds.

Of course, stock and bond returns will vary from year to year, but these long-term annualized forecasts provide a gauge that helps firms construct diversified asset-allocation portfolios that can be tailored to optimize returns for different risk tolerances.

Investment firms also calculate these projections in real terms, which means they factor inflation into their models in addition to other variables such as valuations, earnings growth estimates, and dividend yields to obtain a more accurate assessment of potential total returns. Still, it has become standard practice for firms to issue forecasts in nominal terms because that is what is reflected in client accounts.

As Vanguard’s Aliaga-Diaz explains: “If you start with a $1,000 investment in 2022 and your portfolio returns 10% in nominal terms in 2023, your account will be $1,100. In real terms, your account would be worth $1,080 measured in 2022 dollars.”

Many investors may be gun-shy about embracing bonds, burned by steep double-digit losses this year in their portfolios at a time when stocks fell into a bear market.

The popular investment strategy of structuring portfolios with a mix of 60% stocks and 40% bonds to achieve attractive risk-adjusted returns with lower volatility, the so-called 60/40 portfolio, failed to provide the diversification and balance that made it a tried-and-true investment approach for so long, delivering 10.6% average annual returns for the past 40 years.

The Morningstar US Moderate Target Allocation Index, which serves as a benchmark for the 60/40 strategy, is down 17.53% this year, while the Morningstar US Market Index is down more than 21%.

But what worked so well for so long will work again, say strategists.

“There is a fear and concern that what we saw this year with stocks and bonds coming down together represents a new regime,” says Aliaga-Diaz. “But we will get back to the normal relationship.”

That view has been echoed by others, including Morgan Stanley’s chief cross-asset strategist Andrew Sheets, who has forecast a 10-year annualized return of 6.2% for the strategy. “While we do expect the 60/40 portfolio to deliver lower risk-adjusted returns compared with those over the last four decades, that doesn’t mean it is broken,” he wrote in a report issued this summer.

Starting Points Matter

A key driver of these forecasts comes down to prices: Lower prices point to higher implied returns.

“Starting prices matter,” says Philip Straehl, global head of research and investment management at Morningstar Investment Management. “U.S. valuations have improved dramatically in the last 12 months. There’s been significant repricing in the U.S. equity markets.”

That’s even more true internationally, where stocks have had the added burden of coping with the strong U.S. dollar and weakened local currencies on top of inflation and rising rates. Strategists say developed and emerging markets represent the best opportunities for the highest returns.

Morningstar Investment Management forecasts stocks in developed international countries will return 9.4% annualized over the next decade. For emerging markets, the expectations are even rosier at 11.8%. Vanguard’s outlook for stocks in developed international countries is for annualized total returns of 7.2%-9.2%, and 7%-9% in emerging-markets equities. Research Affiliates is forecasting 13.1% returns annualized for emerging markets over the next 10 years and 12.6% annualized for developed international markets.

“Our recommendation would be to look outside the U.S.,” says John Thorndike, co-head of asset allocation at Boston-based investment manager GMO, which bases its outlook on a seven-year investing time frame. “If you are going to take equity risk, take the bulk of it in non-U.S. value stocks. We think you should take the risk. These stocks are attractive.”

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/54RIEB5NTVG73FNGCTH6TGQMWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZYJVMA34ANHZZDT5KOPPUVFLPE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MNPB4CP64NCNLA3MTELE3ISLRY.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)