5 Supply Chain Issues for Investors to Watch

Many supply chain issues which fueled inflation have eased, but the ripples continue across the global economy.

The worst may be over for the supply chain crisis that led to logjams across the global economy and helped fuel the worst surge in inflation for the United States in 40 years.

However, there continue to be snarls in supply chains, which are the networks between companies and the suppliers needed to turn materials into the products they sell.

- Semiconductors continue to delay output in industries such as automobiles and computer manufacturers.

- Shortages in industrials firms constrain the ability to produce new machinery for factories, and push back efforts to improve manufacturing capacity in a number of industries.

- Packaged food companies are struggling more with shortages in packaging.

Complicating matters for some companies—and stock investors—is that in a handful of industries, supply shortages have turned into gluts, most notably among semiconductors used for personal computers and among clothing retailers.

“Supply chain issues have improved across the board,” says Morningstar’s Michael Field, Europe market strategist. “Things are getting better, but getting back to pre-COVID levels is a multiyear task.”

The Pandemic Supply Chain Crisis

When the onset of the coronavirus pandemic shut down huge portions of the global economy, there was a wave of knock-on effects as businesses shut down and kept workers at home.

Stores were left with empty shelves as congested ports and an undersupply of transportation capacity strangled the ability to move goods around the world. Automobile production came to nearly a dead stop owing to missing semiconductors. That, in turn, led to a shortage of new cars and then to rising demand—and prices—for used vehicles. Likewise, computer components became harder to get hold of as sourcing their materials became more difficult. Homebuilders were also constrained as it became tougher to gather all the necessary materials, such as lumber or drywall, to finish homes.

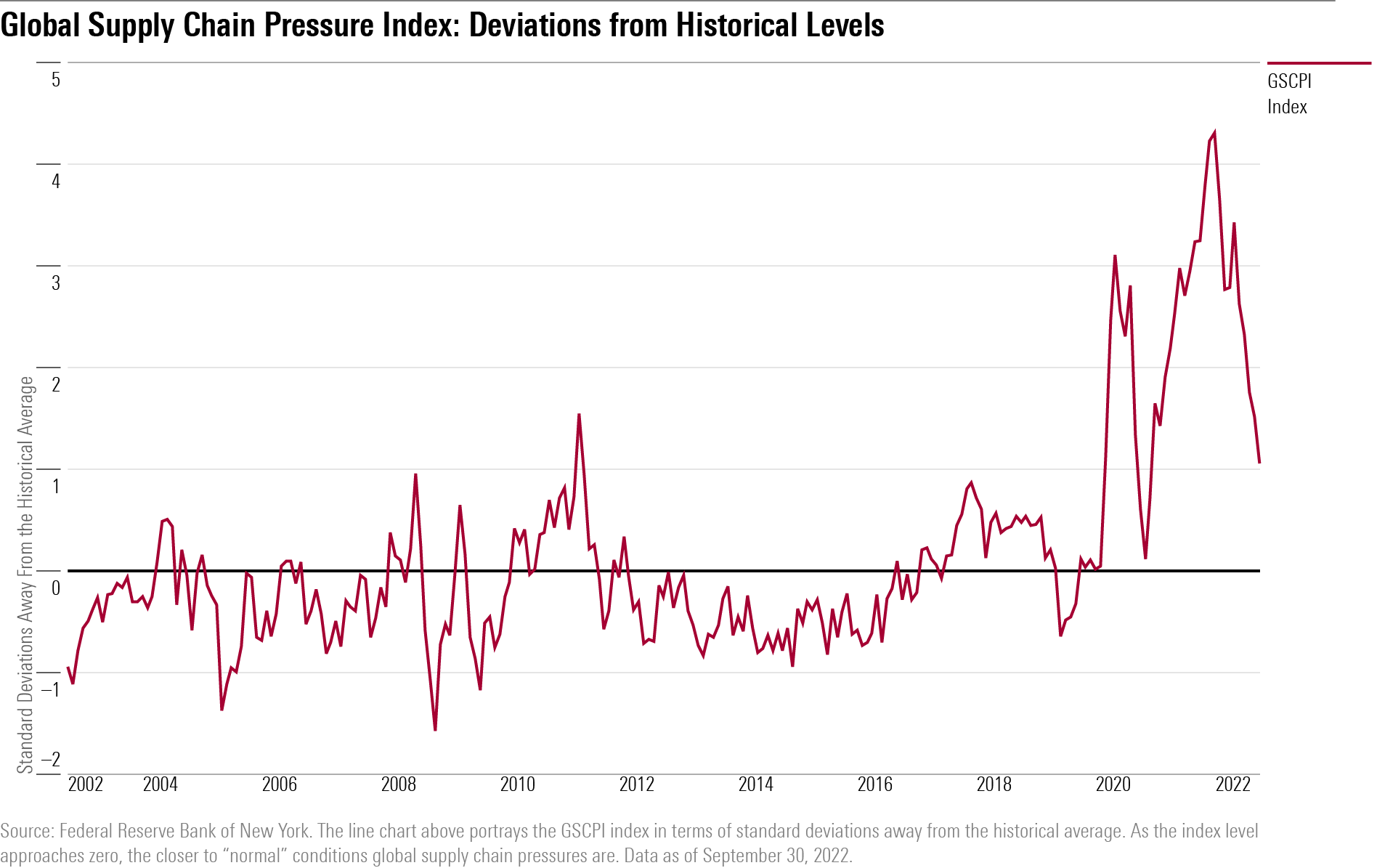

The disruption and reversal of supply chain issues can be seen in the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, which quantifies supply chain pressures. The index showed sequential declines between May and September, bringing down supply chain pressures across the globe closer to historical levels.

Logistic Bottlenecks Are Clearing Up

Last year, two widespread signs of supply chain issues were empty shelves and marked-up prices. As companies scrambled to find ways to move inventory and make sales, shipping and logistics companies were in a sweet spot when it came to profits, even though they were unable to meet the unprecedented rapid surge of demand in the months of the pandemic recovery.

Shipping contract prices rose dramatically, with companies paying historically high rates to move their goods. Walmart WMT and Target TGT even started chartering private ships to stock shelves in preparation for the holidays. The rising cost to move goods was one avenue pressuring prices upward.

Now, a reduction in shipping and transportation log jams has significantly helped ease global supply chain pressures. Shipping companies have added capacity through new ships they ordered, and travelers are flying again, bringing some cargo capacity through commercial airplanes back online, Field says. “The final piece is the fact that supply chain bottlenecks in U.S., Chinese, and European ports are easing up as well.”

Softening consumer demand has also played a role “[Companies] are no longer as desperate to ship stuff as they were before,” says Field. “They’ve got to the level now where inventories are pretty solid.”

As shipping fever has cooled off, so have the stock prices for major shipping companies such as DSV DSV and Maersk MAERSK B, which made record profits at the height of the transportation bottleneck. “People think they’re not going to make the same profits next year,” Field says.

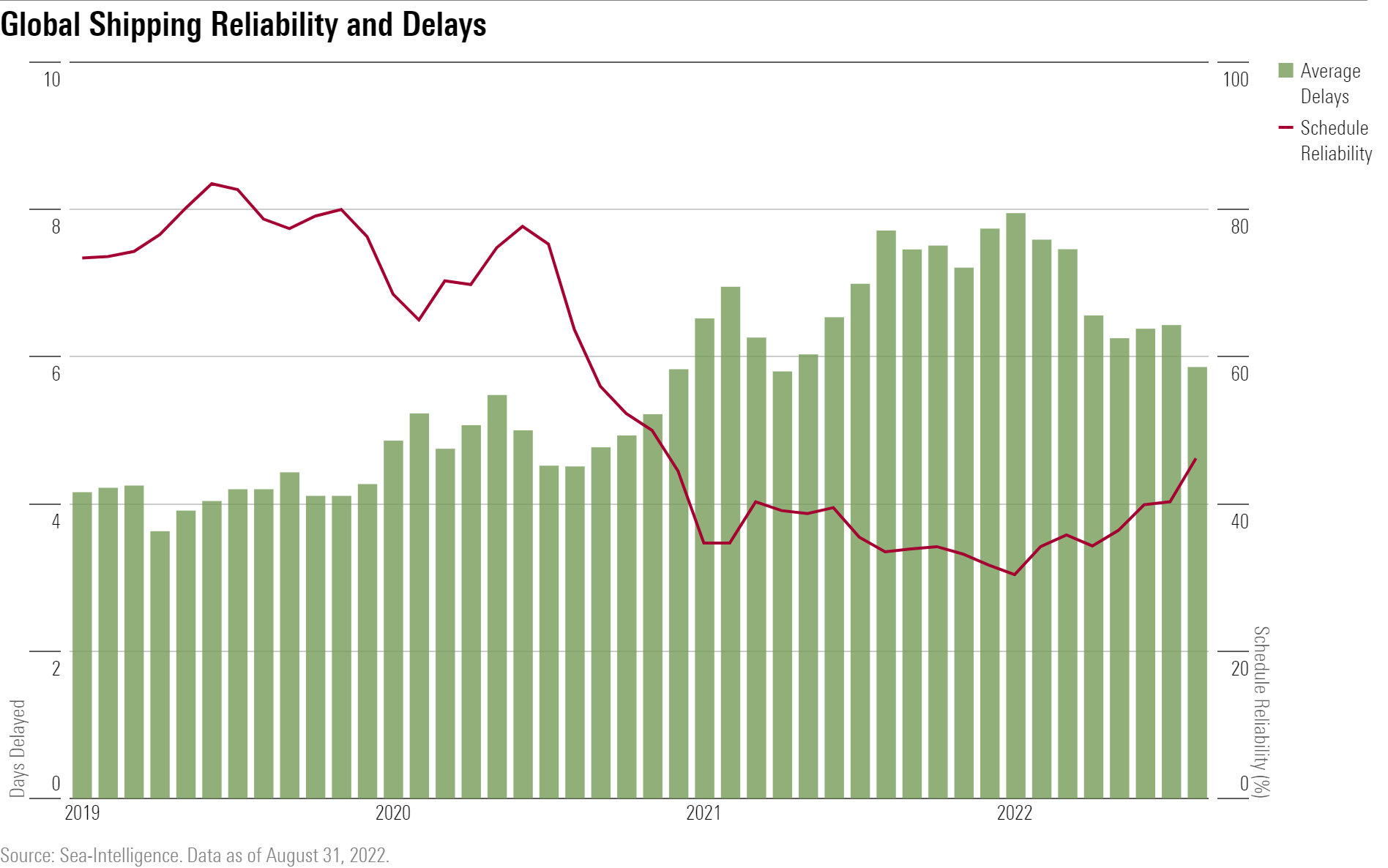

That isn’t to say that everything is back to normal. Shipping delays remain large, with only 42% of goods arriving on time on average in the last three months. While that’s up from the pandemic low of 30%, it’s far from the 2019 average of 78%.

Still, Field says shipping delays should gradually recover in the next few years. “Freight rates are coming down, and that kind of leads everything else.”

A Mixed Picture for Semiconductor Shortages

Semiconductor shortages have plagued a number of industries, but the shortages now are mostly focused on older types of chips, also known as “lagging-edge chips,” that are used in a number of industries including smartphones and network technologies.

“Automotive and industrials are probably the biggest end markets still dealing with this,” says Abhinav Davuluri, Morningstar technology strategist. The semiconductor shortages in the industrials sector also had widespread consequences for several industries as the sector typically develops machinery for factories and production plants.

“Ideally as we enter 2023, we should see a situation where some of the capacity that’s used for more mature chips, especially as demand for PCs and smartphones falls, can be shifted over and some of those chips can go toward industrial and automotive sectors,” says Davuluri.

The good news for industries in dire need of lagging-edge chips is that the smartphone, PC, and data center markets have started to slow down in recent months. That slowdown should free up some capacity at foundries to produce more chips for industries like automobiles.

But the slowdown in demand for PCs and smartphones manifests a problem for companies like Nvidia NVDA, Advanced Micro Devices AMD, and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing TSM.

These companies design and produce modern, or leading-edge, chips that are among the most lucrative to sell. Leading-edge chips, which include those such as graphics cards, used for data centers or high-end computers, and system-on-a-chips, which are used in smartphones. That’s completely reversed now.

“Improvement [in supply] is one way to frame it. I think there’s also just oversupply and excess inventory, which is also bad,” says Davuluri. “A lot of these orders happened when we had massive levels of demand, and that was extrapolated out, but naturally it wasn’t realistic to think that level of demand would continue,” says Davuluri. “All these companies now have these noncancelable orders placed at foundries and are now stuck with those chips,” he says.

Leading-edge chips are also “not really fungible enough to be used in automotive or industrial applications,” according to Davuluri, meaning that these oversupplied chips cannot even be rolled over to industries that are in dire need, as they tend to only utilize lagging-edge chips.

Nonetheless, PCs and smartphones still require some lagging-edge chips to produce, so the falling demand in those markets is still good news for industries still struggling with shortages in those semiconductors.

Automobile Shortages Persist, but That Could Be a Good Thing

While supply chain disruptions have generally improved across the board, part shortages have stubbornly persisted for auto firms. “The big issue is still chips and will remain that way for at least the first half of next year,” says David Whiston, Morningstar industrials strategist.

Inventory for vehicles has still greatly improved from a year ago. U.S. light vehicle inventory bottomed at just below 1 million units in September 2021 and is now at 1.2 million as of August 2022 according to Wards Intelligence. While that’s an improvement, “they are potentially roughly 2 million units lower than where they should be even if automakers follow through on their goal to permanently reduce inventory from prepandemic levels of over 4 million,” says Whiston.

The shortages may have played into automakers’ favor this time around, however. With consumer demand softening, demand for vehicles may take a hit. But for an industry like autos where supply has been extremely limited and slow to climb back up, that’s good news.

“We are not worried that sales will collapse from here, even if the United States enters a recession,” says Whiston. The supply of vehicles is low enough that sales volume could remain strong as inventory improves. In fact, data from Wards Auto Intelligence showed that Ford’s F third-quarter sales were up 17.3% year over year. General Motors GM also reported a 24.3% increase in third-quarter sales from a year ago.

U.S. Food Shortages Don’t Mean There’s a Shortage of Food

Shortages in the food industries, primarily those in the packaged foods space, remain prevalent because of supply chain issues. At the start of this year, there were widespread worries that Russia’s war on Ukraine would lead to food shortages. But that’s not the driver, says Erin Lash, Morningstar’s director of equity research for the consumer sector.

“Most firms have gotten out of Ukraine … that’s not really proving much in the way of a constraint,” says Lash.

Instead, what has been holding back packaged goods companies like McCormick MKC or Campbell Soup CPB is a lack of packaging supplies. Companies are “not being able to find the packaging they need to put their products in,” she says.

Beyond packaging, supply chain issues have also served as a headache for packaged food companies in their efforts to expand manufacturing capacity. Those efforts were impeded by shortages in industries that would produce the necessary machinery for factory expansions, such as semiconductor undersupply for industrial firms.

The good news for packaged food companies is that while supply chain issues are creating higher input costs for them, consumers have been mostly receptive to price increases—one lever of how these firms have been managing cost inflation. “[Sales] volumes aren’t being hit to the extent you would expect from the level of price increases that have occurred.”

Retailers’ Inventory Issues Swing the Other Way

In a sudden reversal from their scramble to stock shelves in 2021, big-box retailers Walmart and Target made headlines when they announced margins would be squeezed as they struggled to clear out excess inventory. Softer consumer demand led to a massive stock of items that buyers were no longer interested in.

On the apparel side, supply chain issues have abated. “The worst of the supply chain disruptions have subsided,” says David Swartz, equity analyst at Morningstar.

Inventory levels have improved for both apparel producers and retailers. While that’s generally great news for producers such as Hanesbrands HBI and VF Corporation VFC, higher inventory levels may pressure the near-term margins of apparel retailers like TJX TJX and Gap GPS. Retailers are expected to discount or hold inventory to next year in their efforts to get it back under control, says Swartz.

Even so, “the increase in inventory is not necessarily a bad thing,” Swartz says. Back in 2021, product shortages left many failing to capture surging demand, but that’s no longer the case. However, the concern for retailer stock investors is now reversed, with fewer product shortages but lower demand. “More inventory has been available in 2022, but sales have been rocky.”

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_ffc6e675543a4913a5312be02f5c571a_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PKH6NPHLCRBR5DT2RWCY2VOCEQ.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/54RIEB5NTVG73FNGCTH6TGQMWU.png)