Bond Ladder ETFs Can Help Investors Climb Higher

Putting money in ETFs with staggered maturities can preserve and even grow wealth in a rising interest-rate environment.

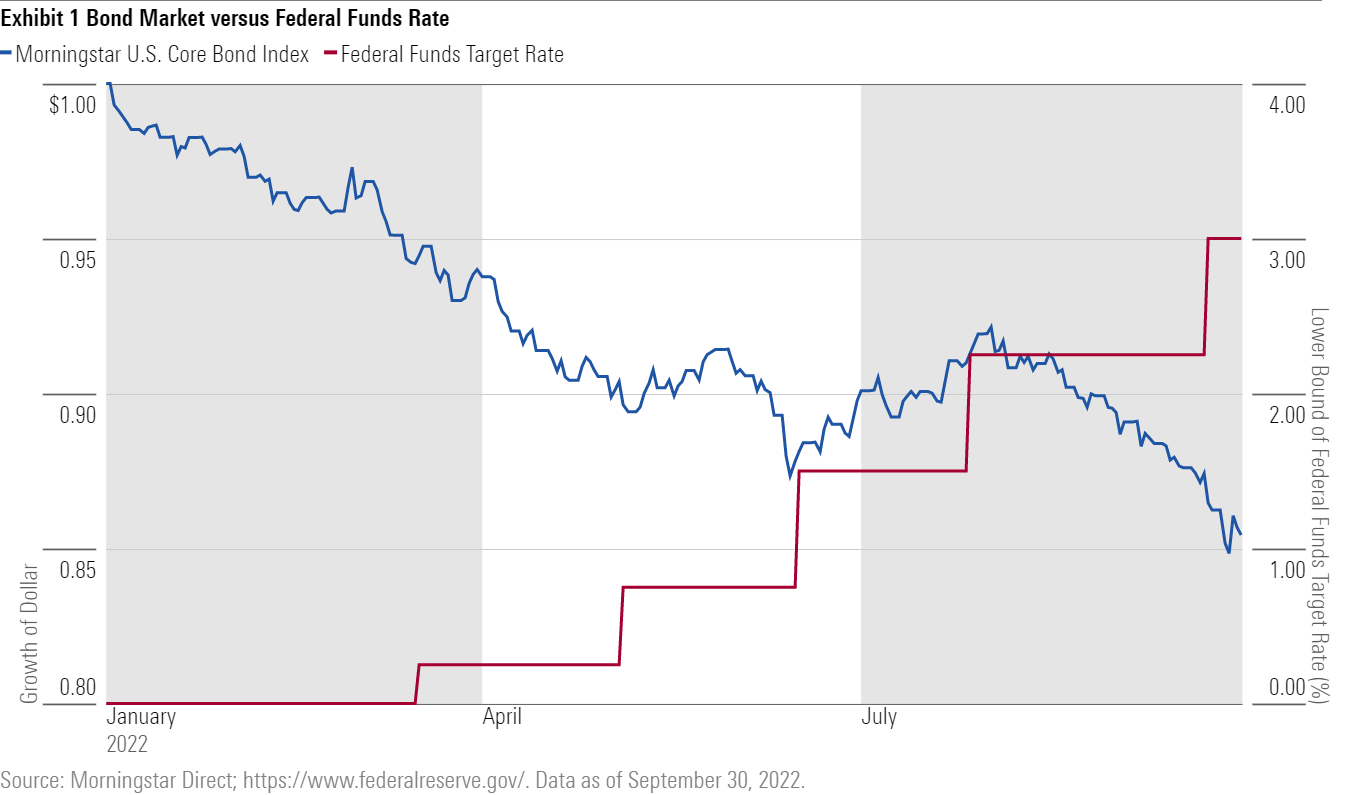

Bond fund investors have learned all too well in 2022 that the prices of existing bonds adjust downward as interest rates rise so that their yield matches that of new issues. Indeed, in its quest to combat inflation the Federal Reserve has already hiked its overnight bank lending rate five times in a row. That, combined with market fears that the Fed may fail, among other things, has led the Morningstar US Core Bond Index—a bellwether—to fall 14.6% this year to date through September, the market’s worst nine-month stretch in decades.

There’s a potential silver lining amid these losses, though. At more than 4% currently for U.S. Treasury bonds of all maturities beyond three months, yields are now high enough that investors may want to consider bonds for their income if not their total return potential. Assuming inflation does not continue to surge, a bond ladder can help them do just that while preserving and even growing wealth amid rising rates. And they are easy to implement through defined-maturity, exchange-traded funds like those offered by iShares and Invesco.

What Is a Traditional Bond Ladder?

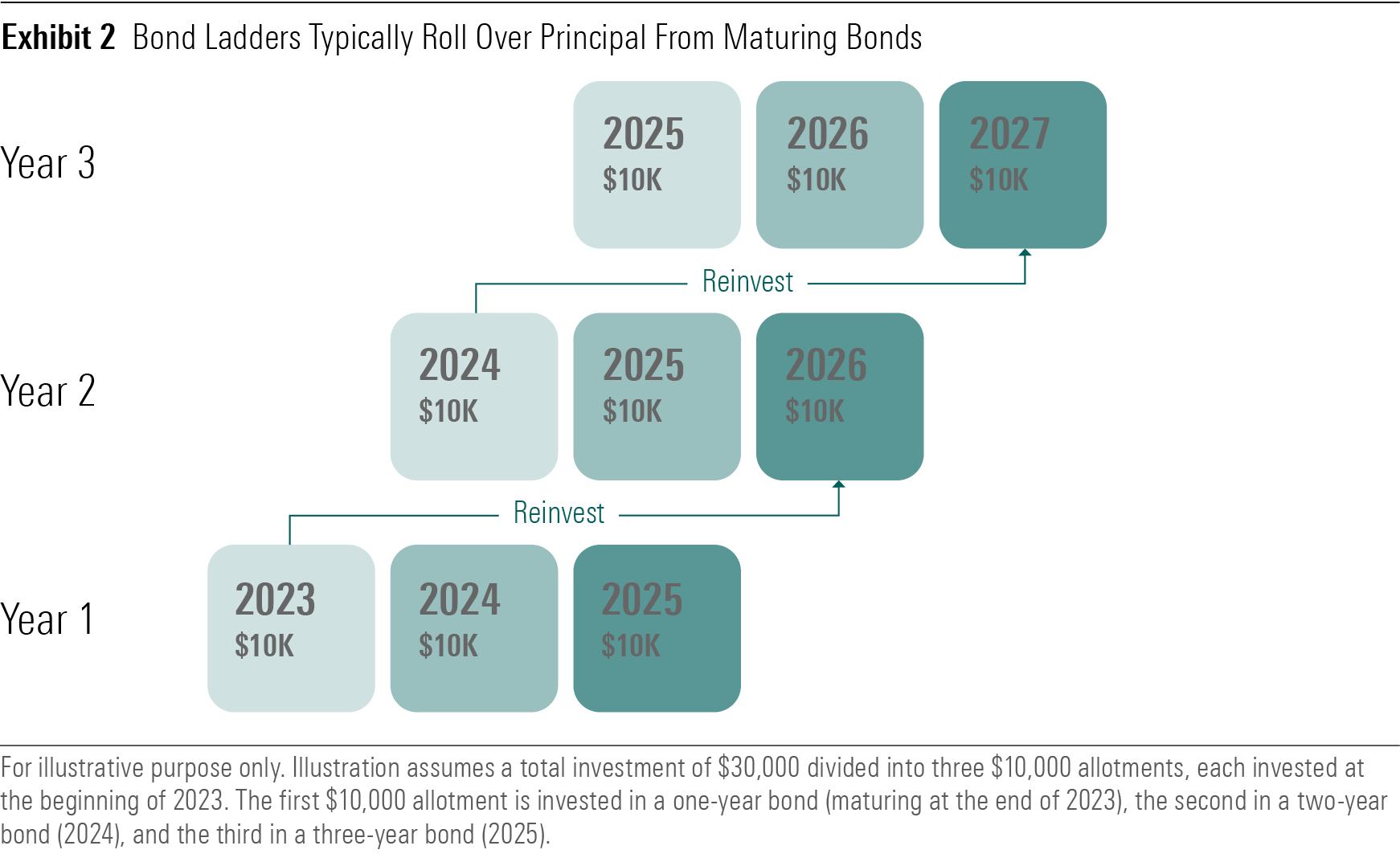

A traditional bond ladder involves building a portfolio of individual bonds, typically non-callable, that mature at regular intervals, and reinvesting the principal in a new longer-term bond every time the nearest-term bond matures. Assuming no defaults, a traditional bond ladder generates a predictable income stream and immunizes the portfolio against permanent losses—provided the bonds are held to maturity and redeemed at par. Moreover, if interest rates rise in the interim, investors can reinvest the principal of their maturing bonds at new, higher prevailing rates. If rates fall, on the other hand, the reinvested principal won’t earn as much as previously, but the bonds in the ladder that have yet to mature will still have the same (now higher rates) locked in.

Defaults can put a dent in what traditional bond ladders return, but that isn’t their only potential drawback. Most center on the challenge of holding individual bonds: Research complexity, the need for ample diversification to guard against defaults, and high trading costs are all impediments. Building and maintaining a traditional bond ladder can require a ton of leg work and prove to be such an expensive and time-consuming affair that it can be out of reach for most investors.

Inflation can also erode the purchasing power of what bond ladders return. A 4% yield each year for the next five would more than compensate investors for the bond market’s current expectation of about 2.6% inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index, over that period. But the bond market could be wrong. Five years ago in early October 2017, for example, it anticipated a 1.73% annualized five-year inflation rate, about 2 percentage points lower than what proved to be the case. A similar mispricing of inflationary prospects over the next five years could lead to less wealth in real terms for bond ladder investors.

Bond Ladder ETFs

For those undeterred by the risk of inflation, defined-maturity ETFs can overcome many, though not all, of the problems associated with building a bond ladder through individual bonds.

Unlike a typical bond fund that hold bonds with a range of maturities and buys new ones when the old ones mature, defined-maturity ETFs try to mimic the behavior of an individual bond. Each ETF sticks to a predefined maturity date by only buying bonds from a purpose-built index that mature in the year the ETF terminates. IShares iBonds Dec 2023 Term Corporate ETF IBDO, for example, holds only investment-grade corporate bonds that mature between Jan. 1, 2023, and Dec. 15, 2023. The fund terminates on the latter date, returning its assets to investors. It does not have a stated “par value,” however, but returns its proceeds to investors at the termination day’s closing net asset value.

A defined-maturity ETF behaves differently than a traditional bond mutual fund. The latter generally targets a particular duration range (a measure of price sensitivity to an abrupt change in interest rates) and will buy or sell bonds through its life to keep it in that neighborhood. A defined-maturity ETF, however, will only replace bonds if they are called or default; otherwise it will hold them until maturation in the year the ETF terminates. Thus, as each ETF approaches maturity, its duration or interest-rate sensitivity will decline, like an individual bond. The overall duration of an ETF bond ladder portfolio, however, will remain mostly stable as long as the maturing proceeds keep rolling into newer, longer maturity ETFs.

ETF bond ladders aren’t without risks. Like a long-dated bond in a traditional ladder, the price of a defined-maturity ETF with years until termination will likely change significantly if interest rates spike early in its life—or in the case of more credit-sensitive funds, if the economy falters. An investor would lock in a loss if forced to sell during that period.

Even for investors able to stomach price volatility, the potential for defaults to destroy capital in riskier strategies remains. The credit ratings agency Fitch, for example, currently anticipates a default rate of 2.5% to 3.5% next year and 3% to 4% in 2024 for non-investment-grade, or high-yield, bonds; emerging-markets ETFs can be vulnerable as well. Investors wary of defaults would do well to stick to defined-maturity ETFs holding investment-grade bonds or U.S. Treasuries.[1]

Should a defined-maturity ETF provider try to enhance its ETFs’ yields by loading them with callable bonds, the actual return could be much lower if those bonds were called away. Most municipal and corporate bonds have a call option that lets borrowers pay them off early, after an initial period of time. That can be problematic for investors who want to put that money back to work as most bonds—like home mortgages being refinanced—are called when prevailing rates are low enough to make it worthwhile.

Investors can gauge call risk by paying attention to the yield-to-worst metric. It shows what the portfolio’s annualized yield would look like if all of its callable bonds were called at their issuers’ first opportunity.

Other risks are unique to the ETF structure itself. Not all bonds in the ETF’s portfolio mature at the end of the year. So, if a bond matures, or is called after the final rebalancing in fund’s termination year, the amount is kept in Treasury bills until the ETF liquidates. Since investors do not have the ability to reinvest the principal here, there’s an opportunity cost incurred by those cash-like holdings. For all these reasons, the payout at maturity could be less than the initial investment amount, and because of the ETFs’—albeit modest—expense ratios.

Building Bond Ladder ETFs

Their risks notwithstanding, ETF bond ladders remain a worthy option to consider, especially those with a maturity of three years or less. Building a longer-term ETF bond ladder isn’t as attractive right now because rates for bonds with maturities of five years or more are less compelling than shorter-term rates.

Building an ETF bond ladder is not difficult, and we can illustrate how one built three years ago would have performed. iShares and Invesco both offer an array of defined-maturity ETFs, each of which holds a variety of individual bonds, ensuring sufficient diversification. Their expense ratios are generally reasonable and their purchase minimums modest, making them quite accessible.

An investor at the beginning of 2018, for example, could have put $10,000 each in Invesco’s BulletShares corporate-bond focused ETFs maturing in 2018, 2019, and 2020. When the earliest ETF liquidated on Dec. 15, the amount could have then been reinvested at the longest end of the ladder—so when Invesco BulletShares 2018 Corporate Bond ETF terminated, its maturing proceeds would have been invested in Invesco BulletShares 2021 Corporate Bond ETF, and so on. A similar bond ladder could have been created using iShares iBonds corporate bond ETFs.

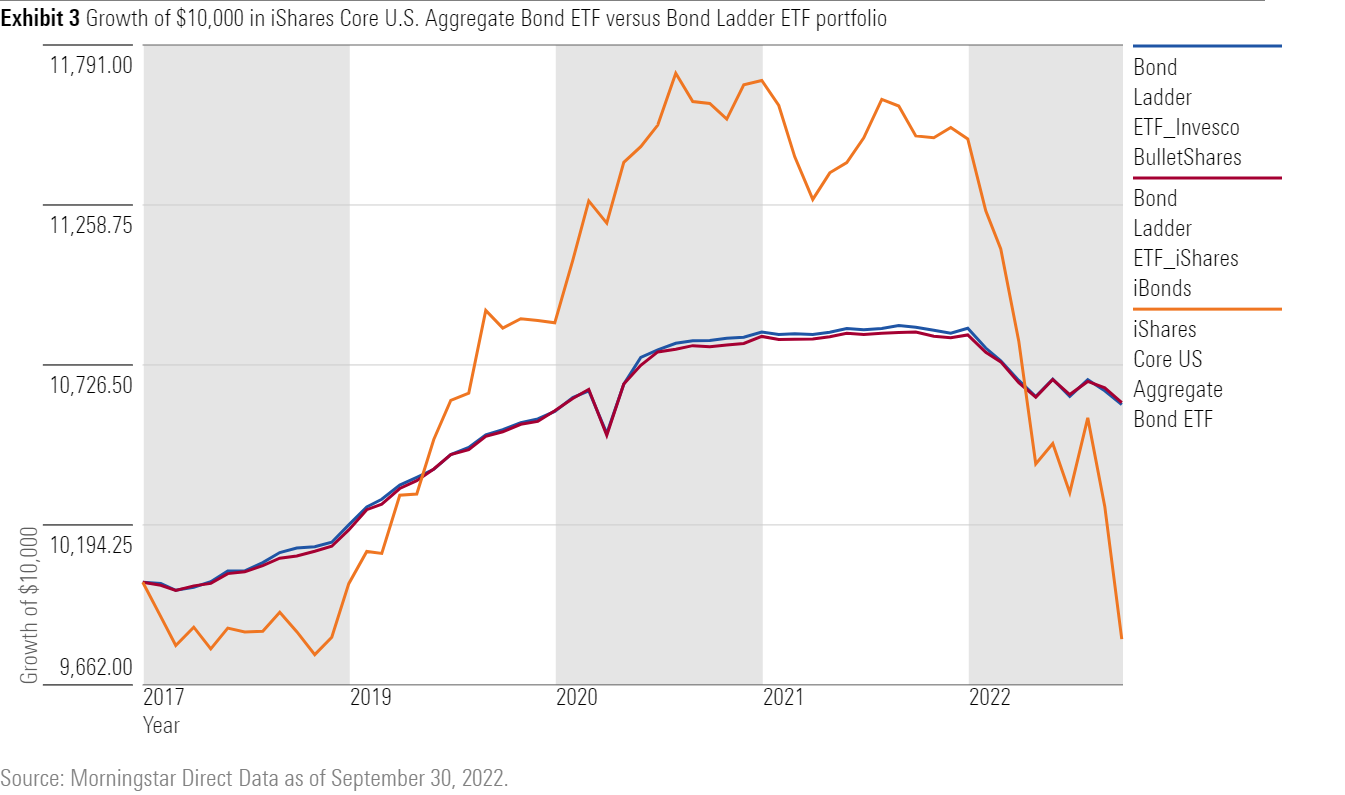

Exhibit 3 assumes the reinvestment of income and compares the growth of $10,000 invested in both these bond ladder ETF portfolios on Jan. 1, 2018, through Sept. 30, 2022, against the iShares Core US Aggregate Bond ETF AGG (an investable ETF that tracks the Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index). While it is hard to differentiate the blue line (the Invesco portfolio) from the red one (the iShares portfolio), they both show an investor in either would have been better off at period end than in iShares Core US Aggregate Bond ETF. That’s because those corporate ETFs then took more credit risk and had less interest-rate risk, which worked well over that stretch.

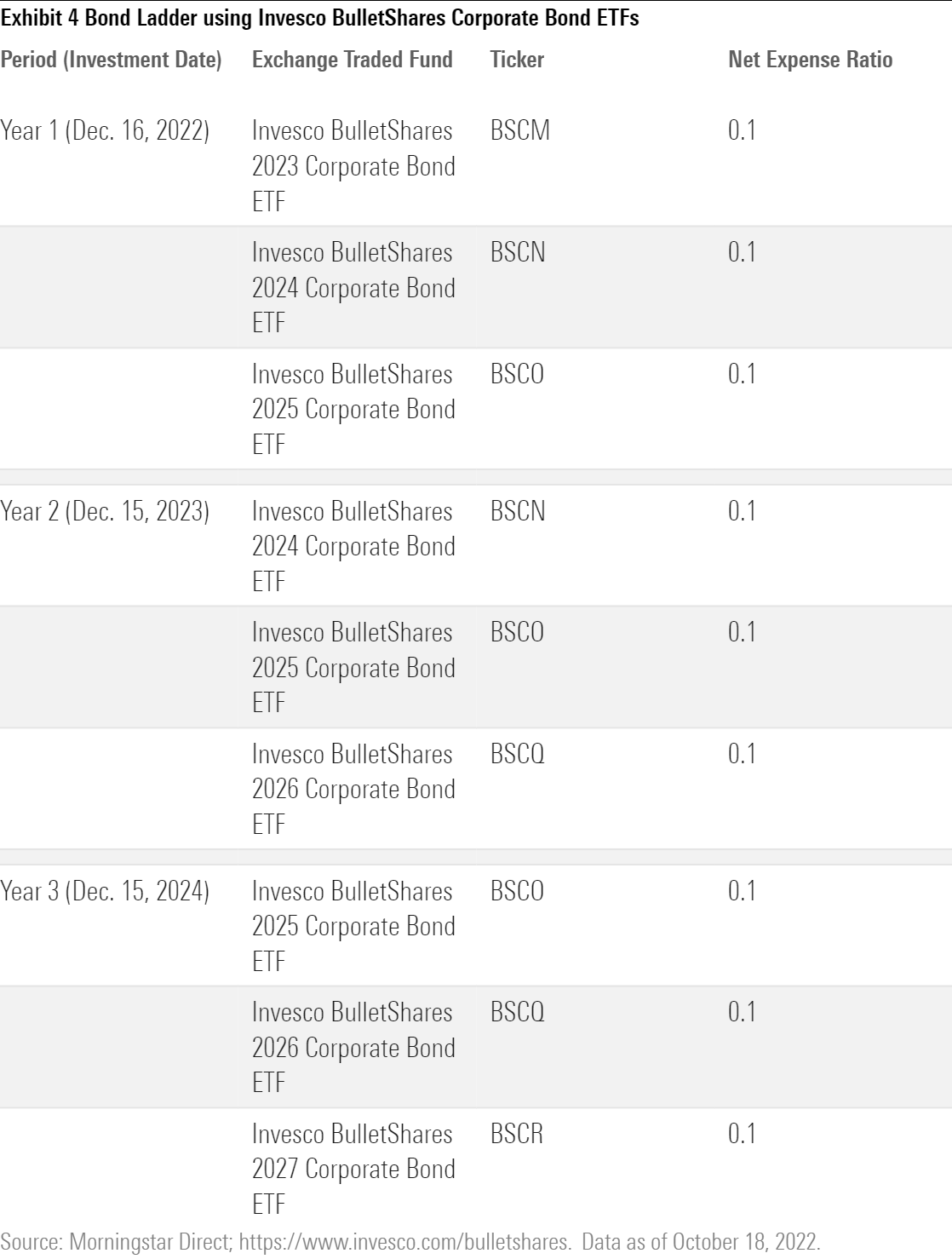

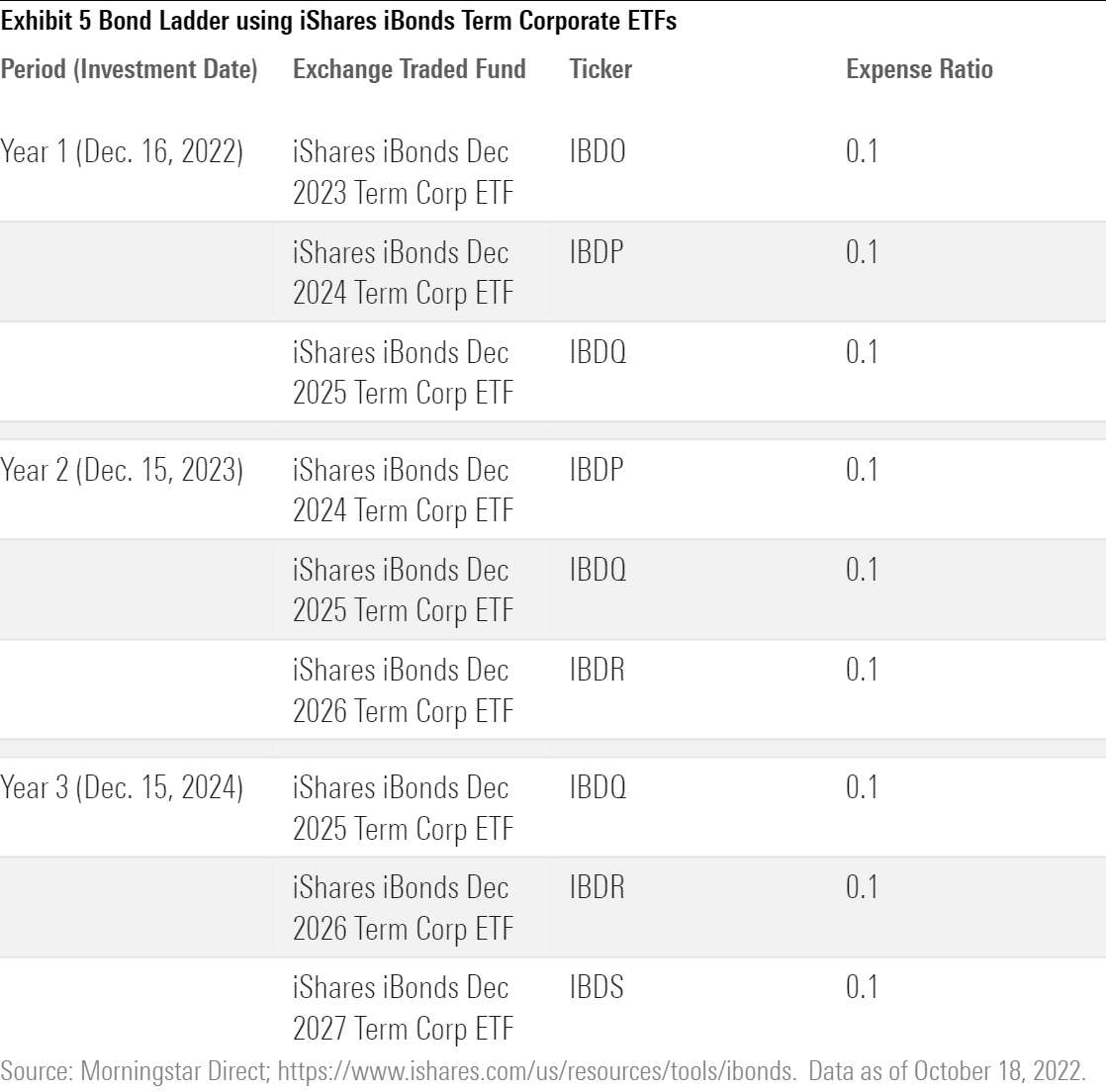

The accompanying tables show how to build a three-year bond ladder portfolio using corporate-bond-focused defined-maturity ETFs currently available in the market:

Investors can build more-complex ETF bond ladders than the ones illustrated here. At present, BlackRock through its iShares’ iBonds offers 33 defined-maturity ETFs, while Invesco through its BulletShares offers 39. These cover various sub-asset classes including Treasuries, municipals, investment-grade and high-yield corporates, and in Invesco’s case, emerging-markets debt. Complicated ladders can obviously expose investors to additional risks, though.

Bond ladder ETFs are not a cure-all. But for investors trying to maintain some stability in a rising yield environment and who are comfortable with the structural risks that come with these defined-maturity ETF bond ladders, they can be an easier alternative to building a ladder with individual bonds.

Endnote

[1] A defaulted bond in Invesco’s BulletShares defined-maturity ETF would be deleted from the BulletShares underlying index at month-end. Invesco portfolio managers would then sell out of that bond, though they would have discretion to sell at the most suitable time for shareholders, generally within a month after the bond’s removal from the index. That could hurt, though. Active managers often hang on to defaulted bonds in the expectation of eventually recovering some losses by getting issued new bonds, equity, and/or equity warrants of a reorganized entity. Selling defaulted bonds out of the ETF portfolio could lock in the worst losses.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/31069962-a596-4b9a-abf7-079fbbeb77ed.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/31069962-a596-4b9a-abf7-079fbbeb77ed.jpg)