Do Currency-Hedged ETFs Have Merit for the Long Term?

They’ve had a great run. But higher expected returns aren’t their main selling point.

Foreign stocks haven’t been immune to the market’s drawdown this year. Currency-hedged exchange-traded funds have absorbed some of the shock, but investors shouldn’t rely on recent success to justify their long-term merit.

From the start of 2022 through Oct. 14, the MSCI ACWI ex USA Index was down 26.6 percentage points. That’s slightly worse than the S&P 500′s 23.9-percentage-point dip.

Losses in local markets only explain part of that decline. Foreign stocks denominated in their local currencies lost 15.6 percentage points over the first nine-plus months of this year, while changes in foreign-exchange rates were responsible for the remaining 11.0 percentage points of the drawdown. The U.S. dollar grew in value relative to foreign currencies during this time, meaning a dollar is worth more euros, yen, and pounds today than it was on Dec. 31, 2021. In doing so, it dragged the performance of foreign stocks lower because foreign investment returns get translated back into dollars at higher exchange rates.

Currency-hedged ETFs provide a potential solution. They attempt to remove most of the currency risk that accompanies foreign investments, and they have lived up to their billing. For example, Xtrackers MSCI All World ex US Hedged Equity ETF DBAW fell by 15.1 percentage points for the year through Oct. 14—a decline that was roughly on par with the local-currency benchmark.

That improved performance is subject to certain circumstances. Currency-hedged ETFs thrive in some situations, but they flounder in others. And hedging has some side effects that should be understood before investing. That said, they have their place as reasonable long-term investments.

The Exchange-Rate Seesaw

Currency-hedged ETFs typically hold a basket of foreign stocks or bonds as their underlying investment along with currency-forward contracts that perform the hedging function. These contracts effectively lock in a predetermined future exchange rate. In doing so, they eliminate the uncertainty of exchange-rate movements.

Currency forwards provide an advantage in certain environments. The future exchange rate in these contracts is tied to the interest-rate difference between the U.S. and foreign markets. Hedging adds to the total return of hedged ETFs when the U.S. interest rate is higher than those abroad. However, it subtracts from their returns when the U.S. interest rate falls below foreign rates. They also protect against changes to the outlook of interest rates in the U.S. and abroad. Recently, higher expected relative interest rates in the U.S. aided the dollar’s strong performance even before the Federal Reserve began raising rates.

That roughly explains the performance pattern of hedged strategies over the past 12 years. Despite near-zero short-term interest rates in the United States, major foreign countries (such as those in the eurozone and Japan) had even lower negative interest rates. The difference meant that hedged ETFs still had the upper hand and often outperformed their unhedged counterparts.

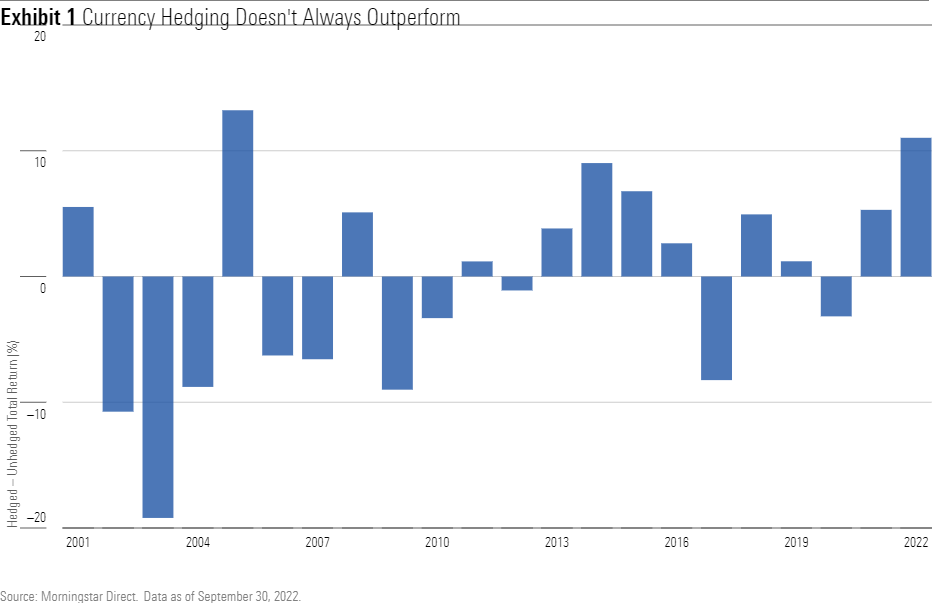

But that hasn’t always been the case. With few exceptions, hedging hurt investors through most of the mid-2000s, when foreign interest rates were higher than the U.S. rate. Exhibit 1 shows the total-return advantage of hedging away currency risk in the MSCI ACWI ex USA Index for each year since 2001.

Historically, the advantage (or disadvantage) of hedging has moved in cycles, making it difficult to forecast the long-term impact. So far, hedging over the long run appears have a more muted effect on the total return of foreign stocks than the dramatic short-term results it produced this year. From January 2001 through September 2022, a $10,000 investment in the unhedged version of the MSCI ACWI ex USA Index grew to $21,936, while the fully hedged version grew to $23,968. That advantage was a recent occurrence, as the hedged index only pulled ahead in June 2022. Said another way, performance will vary depending on the start and end point, but it’s reasonable to expect that hedged and unhedged strategies should provide similar long-term performance.

The Fine Print

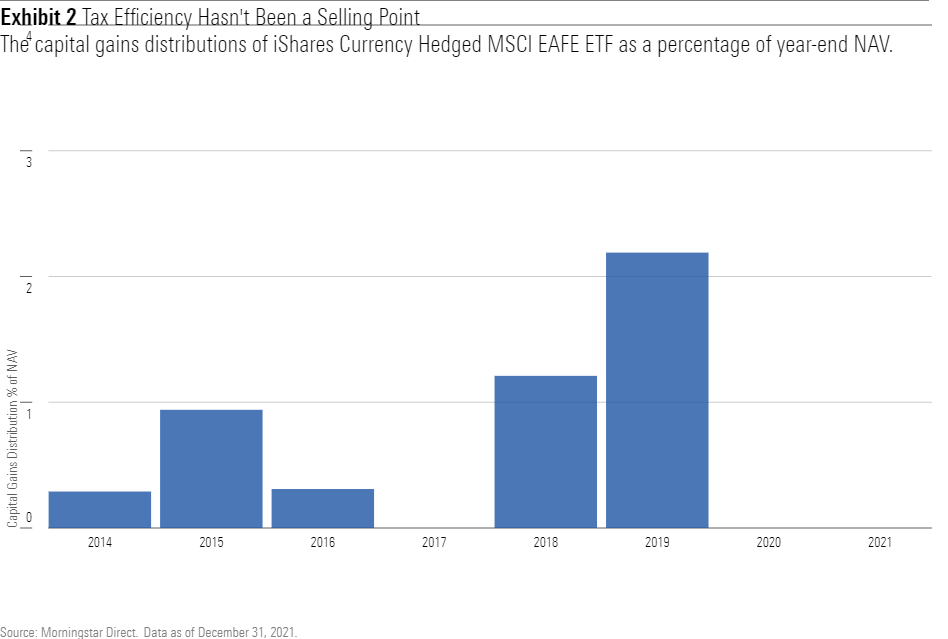

Past performance aside, currency-hedged ETFs possess some undesirable traits. ETFs are typically heralded for their superior tax efficiency over mutual funds. But hedged ETFs don’t always live up to that standard. In most instances, the forward contracts in these ETFs expire at the end of each month, so portfolio managers must sell a soon-to-expire contract and purchase a fresh one to maintain an ETF’s hedge.

These contracts can’t always be purged through the in-kind redemption mechanism that supports an ETF’s tax efficiency. So, the process of refreshing these contracts at the end of each month exposes currency-hedged ETFs to capital gains distributions when the contracts are profitable. Exhibit 2 compares the annual capital gains distributions for iShares Currency Hedged MSCI EAFE ETF HEFA as a percentage of its end-of-year net asset value. For comparison, the unhedged iShares MSCI EAFE ETF EFA has yet to make a capital gains distribution.

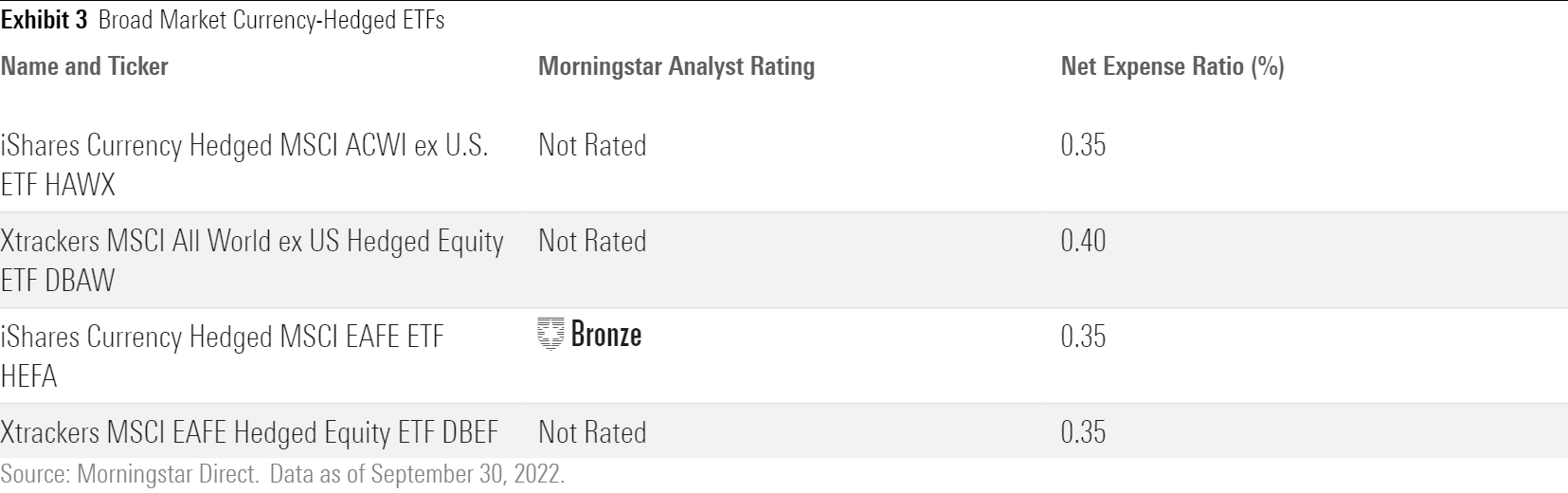

Relatively higher fees also tarnish the long-term merit of currency-hedged ETFs, which charge between 0.30% and 0.40% per year (HEFA levies a 0.35% net expense ratio). Meanwhile, unhedged ETFs tracking stocks from similar markets can be had for less than 0.10%. And there are transaction costs tied to the forward contracts that investors don’t see. Those costs are relatively small, often less than 0.20% in foreign developed markets, but they further erode performance.

Considering the higher fees, a potentially bigger tax burden, and little if any long-term performance edge, why invest in a currency-hedged ETF?

Redemption

In most instances, hedging away currency risk from foreign stocks doesn’t make sense over long investment horizons. But reasonable applications exist.

By design, the forward contracts in these ETFs lock in a future exchange rate, thus eliminating most of the volatility tied to changes in those rates. That means hedged ETFs are often less risky than a comparable unhedged ETF, regardless of the advantage or disadvantage that hedging imparts to an ETF’s total return. For example, the standard deviation of HEFA landed 16% lower than the unhedged EFA over the five years through September 2022.

For that reason, index-tracking foreign-bond funds typically fully hedge away their currency risk because the volatility from foreign-exchange rates often overwhelms the modest volatility of the underlying bonds. Examples of currency-hedged foreign-bond ETFs include Vanguard Total International Bond Index ETF BNDX and iShares Core International Aggregate Bond ETF IAGG.

To that end, hedged ETFs are still reasonable investments for those who want to dial back on risk over a range of investment horizons. But don’t expect them to always provide a performance advantage. Hedging away currency risk may cause these funds to underperform an unhedged strategy for years, depending on the direction interest rates move.

Hedging shouldn’t be considered in a vacuum because the underlying stocks and bonds in these ETFs still drive most of their performance. That means fees and diversification are just as important to the success of these funds as those that don’t hedge. Low-cost ETFs tracking broad indexes, such as those listed in Exhibit 3, are preferable to others that focus on single countries or regions. And ideally, they should be held in a tax-sheltered account.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/78665e5a-2da4-4dff-bdfd-3d8248d5ae4d.jpg)