Say Goodbye to Buy the Dip

BlackRock’s Li says the end of The Great Moderation means investors need to change their thinking about the markets.

Many investors may not realize it, but for the past 40 years the wind has been at their backs when it came to returns on their investments.

For the most part, it was an extended period of low inflation and low interest rates which set the stage for long bull markets for stocks and bonds.

Now, says Wei Li, global chief investment strategist at BlackRock, we’ve entered a substantially different environment where those tailwinds are turning into what will likely be lasting headwinds.

Investors should be braced for an extended period of higher levels of inflation than has been the case in recent decades, Li says, and shorter but sharper swings in the economy that in turn lead to much higher levels of volatility in the markets than we’ve all been used to.

“We have a new regime,” says Li, who has been at BlackRock since 2010.

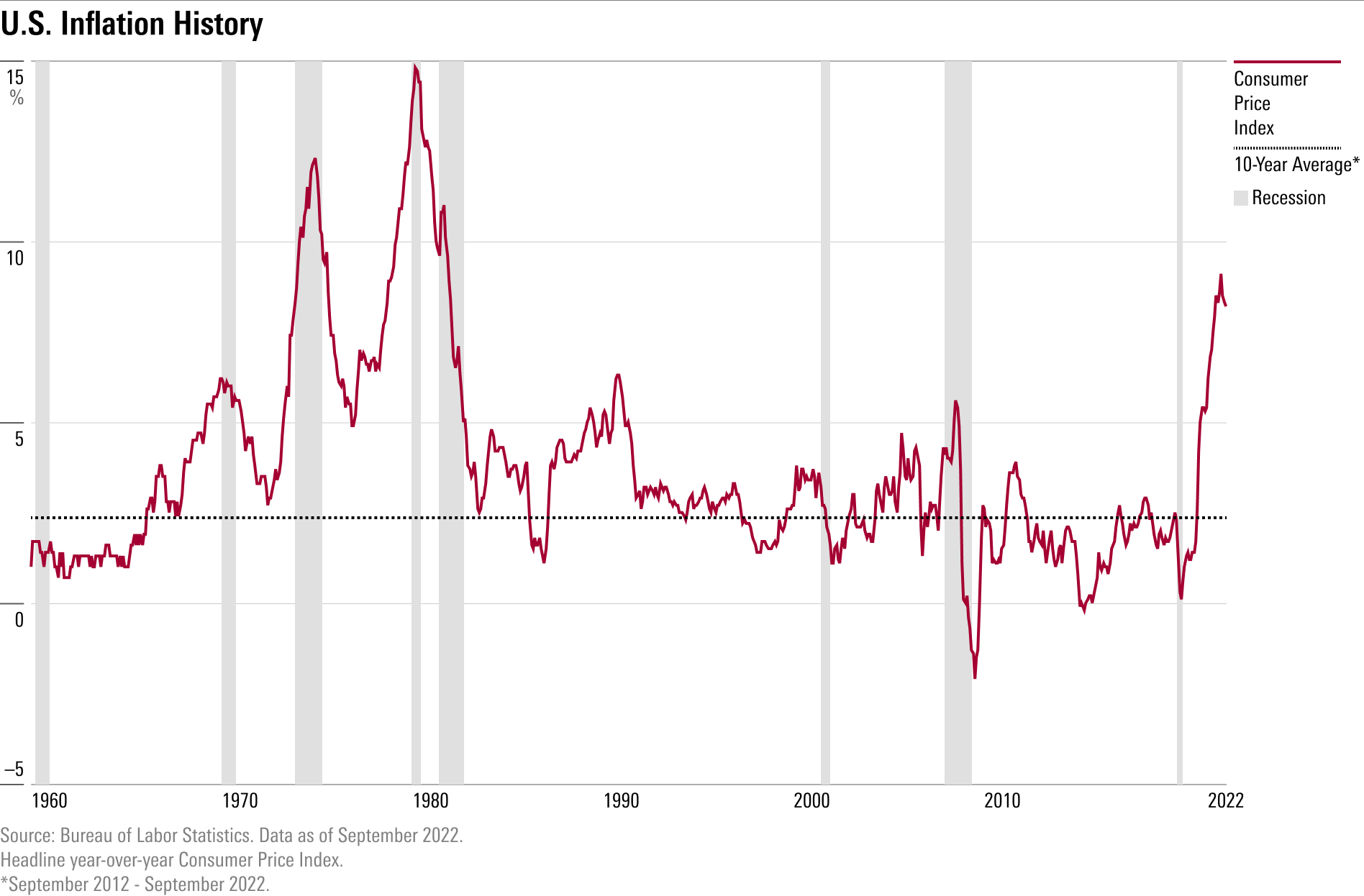

It isn’t just inflation spiking to 40-year highs that is the catalyst for the regime change, Li says. It’s the characteristics of the underlying macro-economic fundamentals that are different, and it’s an environment that could be significantly more challenging for the Federal Reserve and other central banks to navigate. And that will make it more difficult for investors to earn the kinds of returns they have seen over the last few decades.

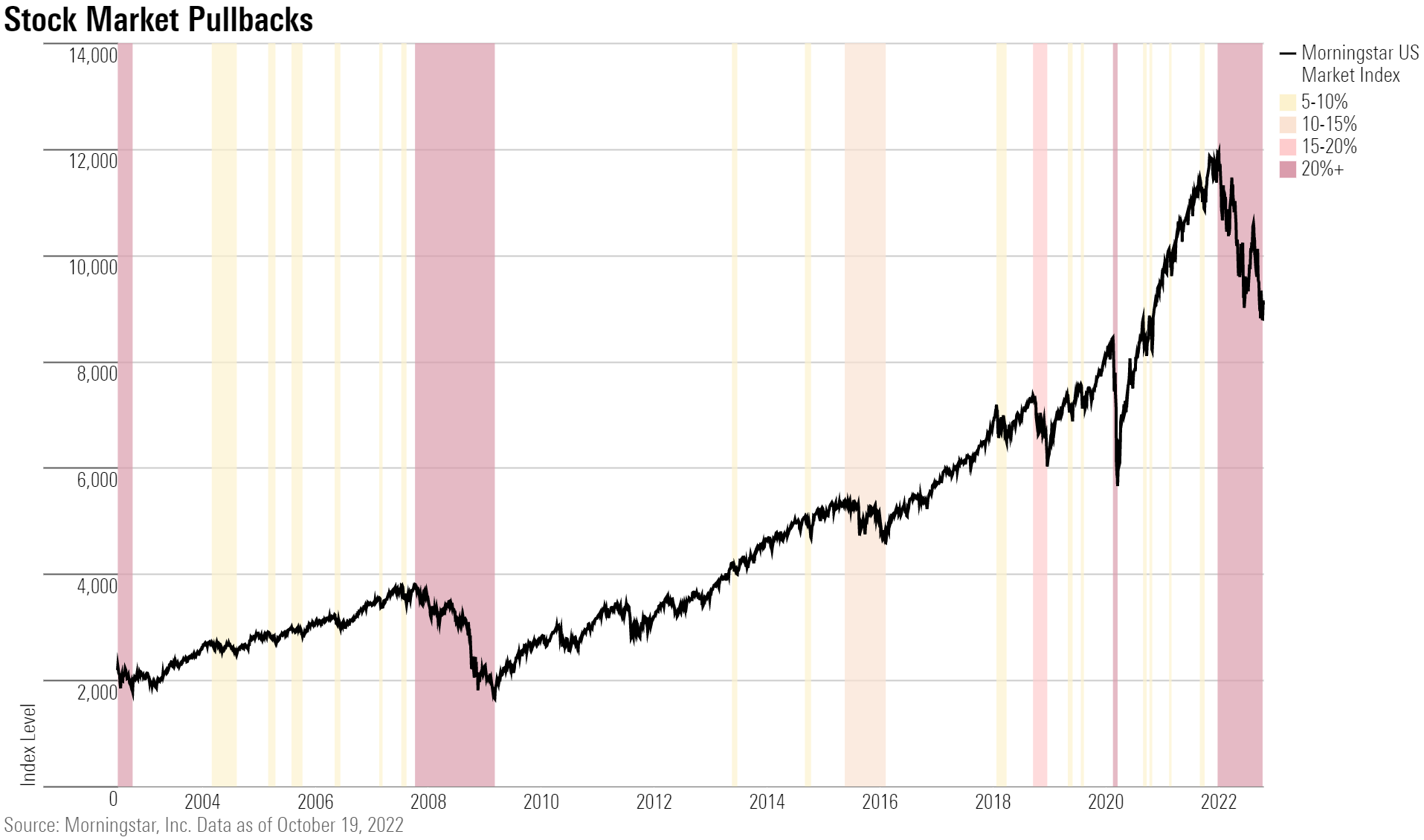

It also means that some rules of thumb from the past four decades no longer apply, in particular, a “buy-the-dip” mentality, where just about any time markets sold off, investors could profit from a quick rebound. Additionally, in an environment without long bull markets, that means the math from the compounding of dividends and income off of bonds will play a greater role in portfolio returns, Li says.

Why The Great Moderation Mattered

Understanding the new economic environment, Li says, starts with looking back at the factors that drove the global economy and markets over the last four decades, a period sometimes called The Great Moderation.

Li and her colleagues at BlackRock note that since the 1980s, the world had seen steadily growing global production capacity. This was thanks to trends such as globalization and the peace dividend following the end of the Cold War, along with favorable demographics and other individual events, such as China joining the World Trade Organization in 2001.

All that excess capacity introduced flexibility into the global economy. So, while excess spending would lead to overheating because economic cycles were driven by demand, the levers controlled by central banks—official interest rates—were able to keep inflation under control and revive stalled economic growth, Li says.

“Central bank tools were very effective in addressing demand,” Li says. “There of course were volatility spikes, but from a broad perspective we had a period of extraordinary low economic volatility,” thanks to the efficacy of interest rates when it came to managing the ups and downs of inflation and growth.

But now, “that has come to an end and we’re in an environment of inflation shaped by supply,” says Li.

A New Inflation Landscape

Two years ago, most people had never heard the words “supply chain.” But in the wake of the pandemic, articles about snarled supply chains and their role in driving up prices around the globe are routinely on the front page.

Li says the current supply chain struggles are symptomatic of a broader shift. “The drivers (of the global expansion of production) such as demographic tailwinds and globalization are all stalling if not reversing,” she says. These trends have been exacerbated by the pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine.

At the same time, the push to address climate change through global Net Zero, the goal of which is to lower greenhouse gas emissions as much as possible, is leading to further supply constraints.

“This is fundamentally different from what we had before,” Li says. “There are these structural forces that make us believe we’re going to be in an environment shaped by supply. In this environment, yes central banks can still hike rates to fight inflation, but the part of the economy that is interest-rate sensitive is not responsible for inflation.”

So, while central banks are going to pull out the stops in raising interest rates to fight inflation, “the cost is going to be much higher,” Li says. For example, “if the Fed is really serious about getting back to 2% inflation in a reasonable period in the U.S., it would represent a 2% shock to the U.S. economy in 2023 and 3 million job losses.”

As a result, “central banks can choose to fight inflation, but it’s going to really hit growth and push up equity risk and the stock market will suffer.”

Say Goodbye to Buy the Dip

The bottom line, Li says is, “in the old environment of The Great Moderation, we were able to enjoy decades long bull markets in both equities and bonds,” she says. “In this new environment, we shouldn’t expect that. Goldilocks is off the table.”

One of the primary casualties of this new dynamic is the “buy-the-dip” approach that became pervasive over recent decades. This was fueled by the easy-money central bank policies that dominated major world economies since the 2008 financial crisis. One aspect of this was known in Wall Street jargon as “the Fed put,” a reference to options trading. The thinking was that whenever stock or bond markets collapsed, the Fed would step in to bail out investors.

“You had a situation where liquidity was lifting all boats,” Li says. “As long you had a long enough horizon, you could just keep buying the dips and that would get you to a good place.”

Now, investors will need to consider the macro-economic backdrop before bottom-fishing.

“Today investors need to understand what is driving the correction,” Li says. “The automatic, buy-the-dip reflex will not be working.”

Revisiting the Bond Market Playbook

When investors begin to believe there is a rising chance of a recession, usually the response is to buy bonds, which pushes up prices and drives down yields. That allows bonds to be a safe harbor ahead of an economic slowdown, which is usually a time when stocks fall.

But as has been the case throughout 2022, that playbook for bonds hasn’t been working, and it’s one that Li says investors should reconsider. The first reason, as has been evidenced this year, is that in an environment of higher inflation, central banks are more inclined to continue raising rates even as the risk of recession grows. Those interest rate hikes push down bond prices.

Investors have also grown used to central banks rapidly cutting interest rates when economies weaken. But against a backdrop of persistent inflation, “we don’t see them cutting rates like they typically do in recessions,” Li says.

Lastly, with government debt at already high levels, Li says bond yields may stay higher than was the case in the past, as investors look for greater compensation from the risks of owning government bonds.

When would this dynamic change? Investors will need to wait for the Fed to hold rates steady, or even start cutting them, before Treasury bonds could turn positive, Li says.

But, Li says, “right now the focus is on fighting inflation, and the most recent CPI (Consumer Price Index) reinforces our expectation that the Fed is going to overtighten in restrictive territory.” It is only when the damage to the economy is clear will the Fed stop, she says.

Li adds that she does see value for investors in short-term government bonds, where yields have now risen to around 4%.

Dividends and Compounding Back in Fashion

In an environment of big, extended bull markets the bulk of returns come from price appreciation. But in choppier, back-and-forth markets, income generated by investments plays a greater role in returns. “Another way of saying it is that it’s important to take advantage of compounding … and stay invested,” Li says.

In addition, the stock market more broadly may also favor dividend-producing stocks, Li says. She notes that in a higher interest rate environment, the value of future cash flows are discounted more heavily—in other words, are worth less today—because the cash flow an investor can get today has a higher value. “That makes quality dividend growers more interesting,” Li says.

Keep an Eye on Your Portfolio

More volatile markets means that allocations among different kinds of investments can more easily be thrown out of whack. “In this environment, it’s important to review your portfolio composition more frequently, and not let your allocations drift,” Li says.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed529c14-e87a-417f-a91c-4cee045d88b4.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T5MECJUE65CADONYJ7GARN2A3E.jpeg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_ffc6e675543a4913a5312be02f5c571a_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed529c14-e87a-417f-a91c-4cee045d88b4.jpg)