Will the Bridge Strategy Weather Social Security Reform?

The government’s shaky fiscal footing could change the math on the best way to increase inflation-protected retirement income.

One of the most powerful ways for retirees to increase inflation-protected income is the Social Security bridge strategy: waiting to claim until the maximum claim age, while taking larger withdrawals to fund retirement expenses in the interim. In fact, in a recent study, my colleague Aron Szapiro and I concluded that this strategy generally beats private-annuity-based strategies.

However, making Uncle Sam your de facto annuity provider comes with a big risk: The government forecasts that the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund, which funds Social Security benefits, will run out of money by 2034. In new follow-up analysis, we investigate the potential impact of possible Social Security reforms on the bridging strategy. (Our full analysis on this topic is available in our report, “The Quest for Lifetime Income: Will the Bridge Strategy Weather the Approaching Storm of Social Security Reform?”)

Surprisingly and comfortingly, we found that the bridging strategy will likely retain its status as one of the top lifetime income strategies for many to consider even under various possible Social Security benefits reforms. So, retirees should still consider bridging going forward. The reason is that most proposed changes would reduce the base Social Security benefits, meaning that early claimants and late claimants would see similar benefit cuts.

Of course, if Congress reduces the value of the delayed-retirement credit, the bridging strategy may become eclipsed by a private-annuity-based strategy. In fact, bridging would lose out to private annuities if the delayed retirement credit were reduced to 6% per year from 8% per year. (No one has proposed this recently, but it remains a risk.)

How We Defined the Strategies

We consider several different strategies in this article to assess how well the bridge strategy would work in comparison:

- Portfolio only. Use Social Security benefits, claimed at retirement (which we assume is at 65), and systematic withdrawals to fund expenses in retirement.

- Social Security bridge. Delay claiming Social Security until age 70, taking larger withdrawals to fund retirement expenses before Social Security benefits start.

- Fixed single premium immediate annuity, or SPIA, at retirement. Purchase a fixed SPIA with a portion of wealth at retirement and use Social Security benefits and portfolio withdrawals for remaining expenses.

Social Security Reform Options

There have been many proposed policies to address Social Security’s funding shortfall, all of which either cut benefits, raise taxes, or propose a combination of the two.

We explored the options for Social Security reform that would lower benefits to see what different approaches would mean for the usefulness of the bridge strategy.

- Modifying the primary insurance amount formula. These changes typically come in the form of adding an additional bend point in the formula or modifying the primary insurance amount, or PIA, factors. This type of change would typically reduce Social Security income for most beneficiaries. For example, suppose policymakers lower the 15% PIA factor to 7.5%. This would result in a 50% decrease to the average indexed earnings over the second bend point that is used to calculate the PIA.

- Reducing cost-of-living adjustments. Policymakers have proposed changes that would reduce the cost-of-living adjustments, or COLAs, that are currently applied to Social Security benefits. The most common proposal is to index benefits to the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, or C-CPI-U. Another approach put forth recently calls for eliminating COLAs altogether for beneficiaries with a modified adjusted gross income, or MAGI, above certain thresholds.

- Increasing the normal retirement age. Policymakers have also considered increasing the normal retirement age, which would lower benefits for all new Social Security beneficiaries. This could be done by promulgating a new retirement age (for example, 68), or policymakers could index normal retirement age to life expectancy, meaning that the normal retirement age would gradually increase with birth year.

- Reducing the delayed-retirement credit. Under current law, if eligible plan participants delay claiming Social Security until after normal retirement age, their benefit will increase by 8/12 of 1% per month, or 8% per year until age 70. This is referred to as the delayed-retirement credit, or DRC. Recent proposals have not included a provision to reduce the DRC. However, this is the change that would have the most direct impact on the bridge strategy, hence we included it in our analysis.

Refer to our full report for more detail about the regimes we studied and our analytical framework.

We Believe Social Security Bridging Will Likely Remain One of the Best Lifetime Income Strategies, Even After Social Security Regime Reform

We started our analysis by focusing on the changes to Social Security we outlined above that would reduce the base Social Security benefit. This included everything except for the changes to the DRC.

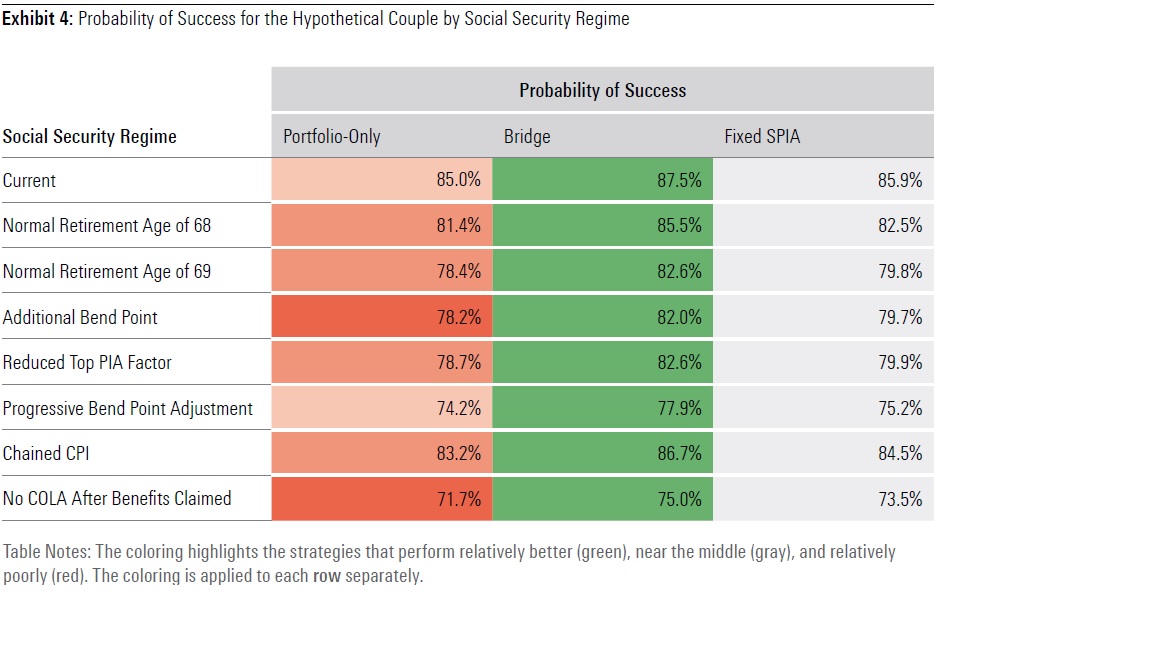

We found that in all cases, the Social Security bridge strategy was the top performer, beating out the other strategies in terms of probability of success, as demonstrated in Exhibit 4 from the full report.

This pattern of results occurred because all these changes reduced the base Social Security benefits at age 65, meaning that all strategies were more or less equally affected. For example, the C-CPI-U regime change would scale down the benefits provided by Social Security because COLAs will likely be reduced, but this reduction would apply to all Social Security benefits, regardless of when they are claimed.

If Congress Reduces the Value of Delaying Claiming to 6% per Year From 8% per Year, Bridging May Be Less Attractive Than Buying an Annuity

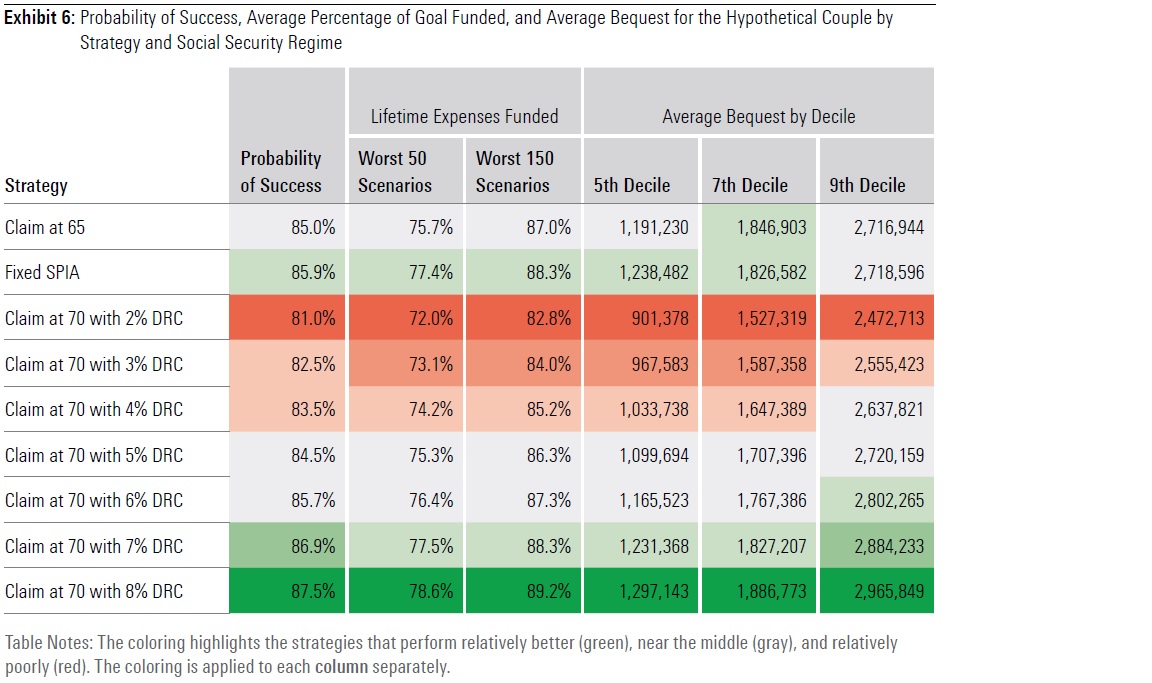

Next, we studied the potential impact if policymakers lowered the DRC. Under our assumptions, we found that if policymakers set the DRC to 6%, the Social Security bridge would be eclipsed by the fixed SPIA strategy, as demonstrated below.

The results show that bridging is the best strategy when the DRC is 7% or 8%. However, if the DRC is 6% or lower, the fixed SPIA strategy provides a higher probability of success, lower shortfalls, and generally larger bequests. This occurred because reducing the DRC hurts only the bridging strategy and does not affect the base Social Security benefits claimed at 65.

While the specific threshold is sensitive to our assumptions, the point is that a lower DRC can significantly reduce the efficacy of the bridge strategy, unlike the other changes that cut Social Security benefits across all strategies.

The Bridging Strategy Is Likely Still the Best Path Forward

Under most of the potential Social Security regime reforms that have been proposed in the past five to 10 years, we found that the Social Security bridging strategy would likely still outperform private-annuity-based strategies.

However, if Congress opts to reduce the DRC, the Social Security bridging strategy may be overtaken by an annuity-based strategy. The bottom line: Retirees should continue to think about bridging, and future retirees should not write off the idea—at least not yet.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/478a471a-aa07-4241-afd4-40cf325f3951.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/U772OYJK4ZEKTPVEYHRTV4WRVM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/478a471a-aa07-4241-afd4-40cf325f3951.jpg)