3 Reasons International Investing Hasn’t Paid Off

The strong dollar has been a problem, but not the only one.

Investors who own international stocks have been sorely tested lately. As the U.S. stock market has dropped into bear-market territory, non-U.S. stocks have lost even more than their domestic counterparts so far this year, after falling behind by more than 17 percentage points as the market rallied in 2021. Things don’t look much better over the long term. A $10,000 investment in international stocks in September 2012 would have grown to about $17,000 by August 2022, compared with more than $33,000 for an investment in U.S. stocks.

At risk of oversimplifying things, there are three major reasons why international investing hasn't paid off. Two of the three might be temporary, but the third has been a persistent secular trend that may not reverse.

Problem Number One: The Strong Dollar

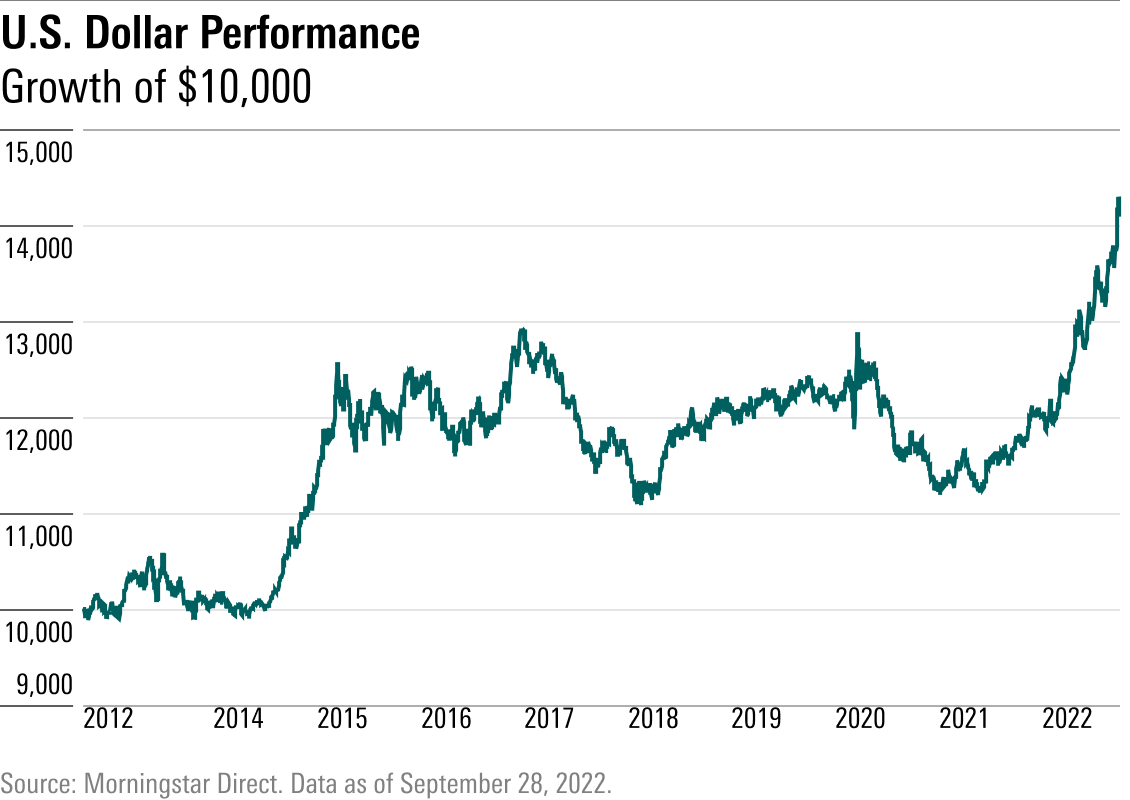

As my Morningstar colleague Sandy Ward recently pointed out, the U.S. dollar has recently enjoyed its strongest run in 20 years. During a time of significant geopolitical and economic turmoil, the greenback has benefited from its status as a safe-haven and global-reserve currency. In addition, rising interest rates have pushed yields on U.S. bonds higher, increasing their yield advantage versus bonds in other major markets, such as Germany, Japan, and Canada. Over the trailing one-year period through Sept. 28, 2022, the dollar gained about 18% against a basket of major currencies.

The dollar has also had a decent run over longer periods. During the 10-year period from 2010 through 2019, for example, it gained an average of 3.9% per year against other major currencies. Part of this reflects the tapering off of the U.S. Federal Reserve's quantitative easing program while the European Central Bank and other central banks around the world started more aggressive economic stimulus programs, which increased the amount of currency in circulation in those markets. The U.S. dollar also benefited from an improving trade balance and a lower federal deficit.

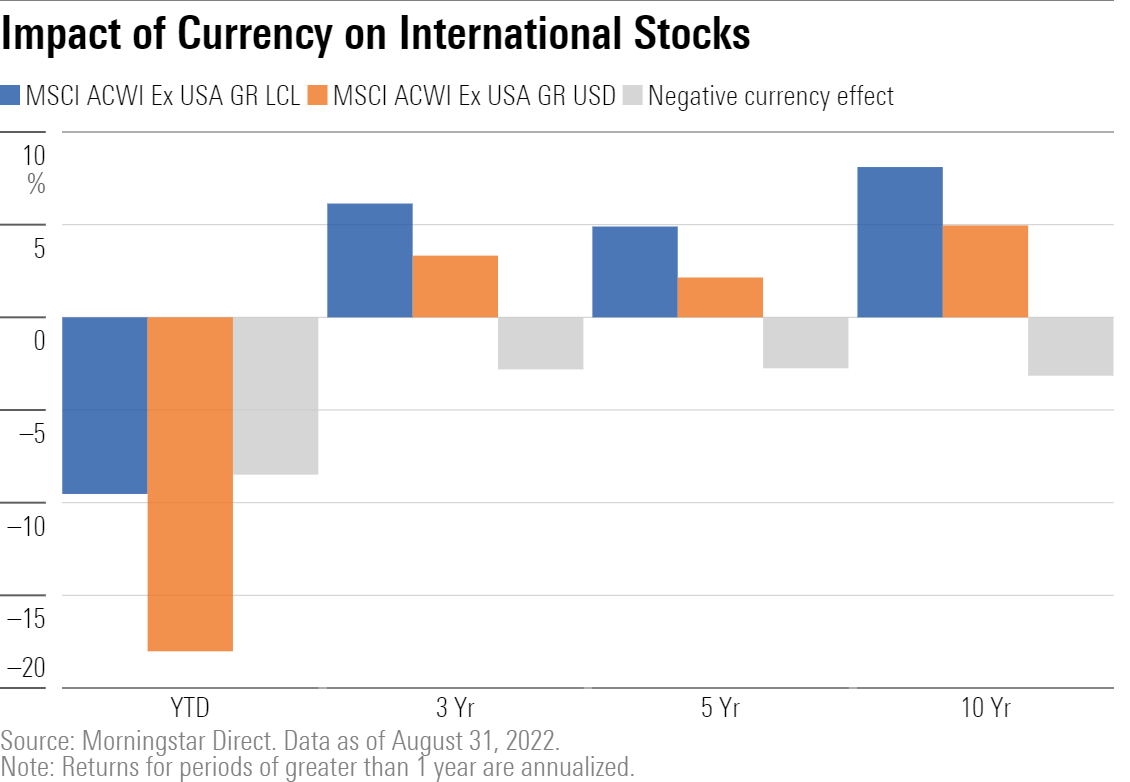

While the U.S. dollar has gone from strength to strength, other major currencies have suffered. The British pound, for example, has dropped more than 20% so far this year, driven lower by inflationary pressures, a growing budget deficit, and a struggling economy. Other major currencies, such as the euro, Japanese yen, and Chinese renminbi, have also dropped lower. Weaker non-U.S. currencies mean lower returns for investors in international funds after returns are translated back to U.S. dollars. For example, the local-currency version of the MSCI ACWI ex USA Index has actually held up relatively well in 2022's bearish market, with a return of negative 9.5% through Aug. 31, 2022. After the effect of currency translation, though, the benchmark posted losses of more than 18.0%.

The impact of currency translation has been particularly painful this year, but it has also contributed to the poor showing of international stocks over longer periods. Over the past 10 years, for example, currency effects have reduced international-stock returns by more than 3 percentage points per year, on average.

Problem Number 2: Better Earnings-Growth Rates in the U.S.

Currency translation doesn't explain all of the shortfall, though. Even without the currency effect, international indexes still fell behind their domestic counterparts by more than 4 percentage points per year, on average, over the trailing 10-year period. Simply put, companies based in the United States have generated higher earnings-growth rates, and investors have generally been willing to pay up for better corporate earnings. Over the trailing four years, for example, U.S.-based companies have compounded earnings at a 25% annual clip—close to 3 percentage points higher than companies based in non-U.S. markets. The novel coronavirus slowed economic growth globally in early 2020, but gross domestic product growth bounced back quickly, especially in the U.S.

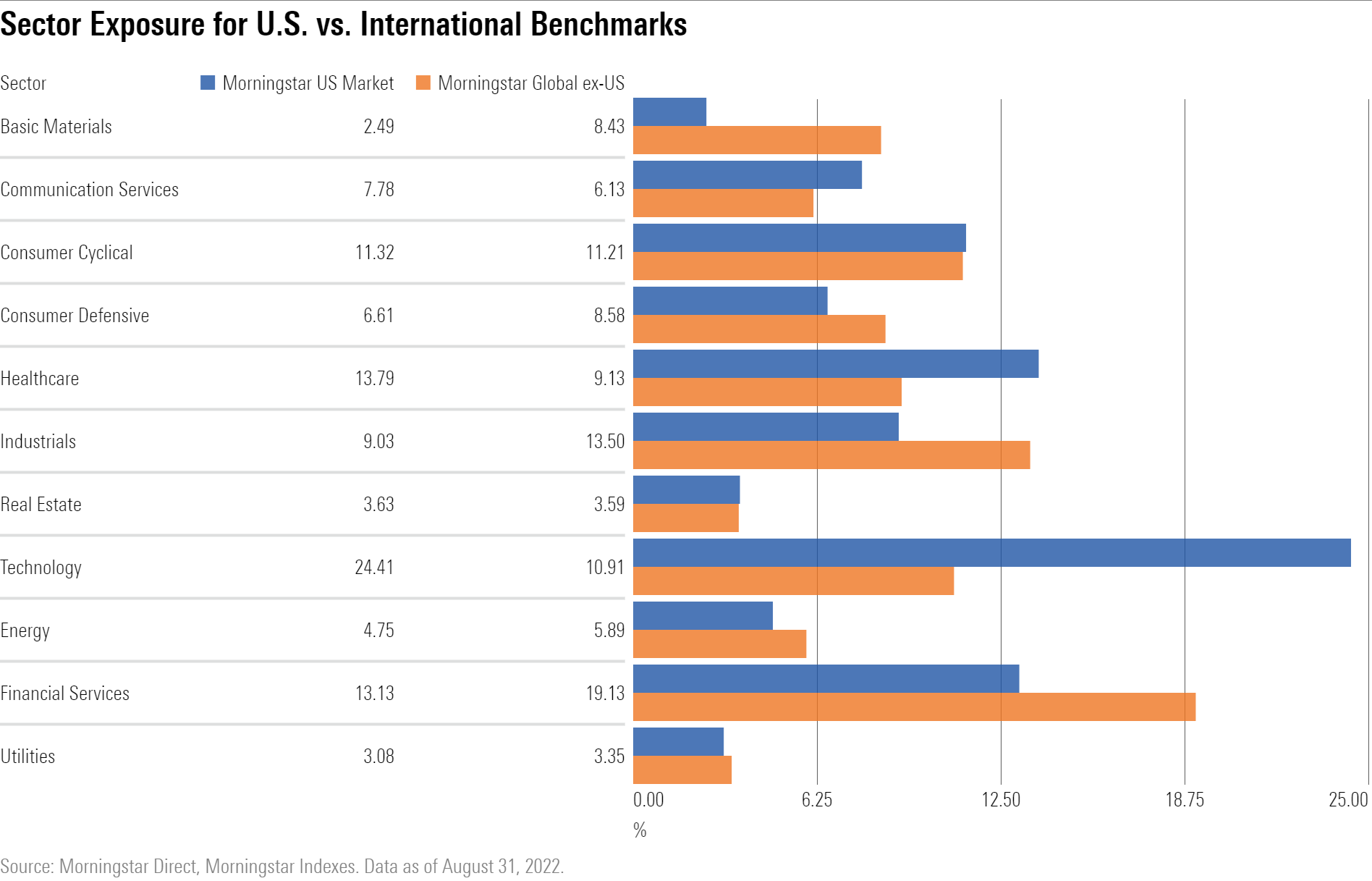

Part of this growth advantage owes to differences in sector exposure. As shown in the chart below, U.S. stock benchmarks have significantly heavier weightings in fast-growing sectors, such as technology and healthcare. Non-U.S. stocks, on the other hand, have heavier stakes in cyclical areas, such as basic materials and industrials. Bigger stakes in slow-growing, heavily regulated areas such as financials have also weighed on returns.

This divergence in sector exposure may not always work in U.S. stocks' favor. Indeed, non-U.S. stocks briefly pulled ahead in late 2020 and early 2021 as other global economies recovered. Non-U.S. stocks also benefited from the market's shift toward value stocks. International stocks have also had an edge over some longer stretches in the past, such as 1983 through 1988 and 2002 through 2007.

As mentioned above, international stocks have also outperformed in local-currency terms more recently. This coincides with the shift toward cyclical stocks but could turn negative again if global economies dip into recession.

Problem Number 3: Upward Trend in Correlations

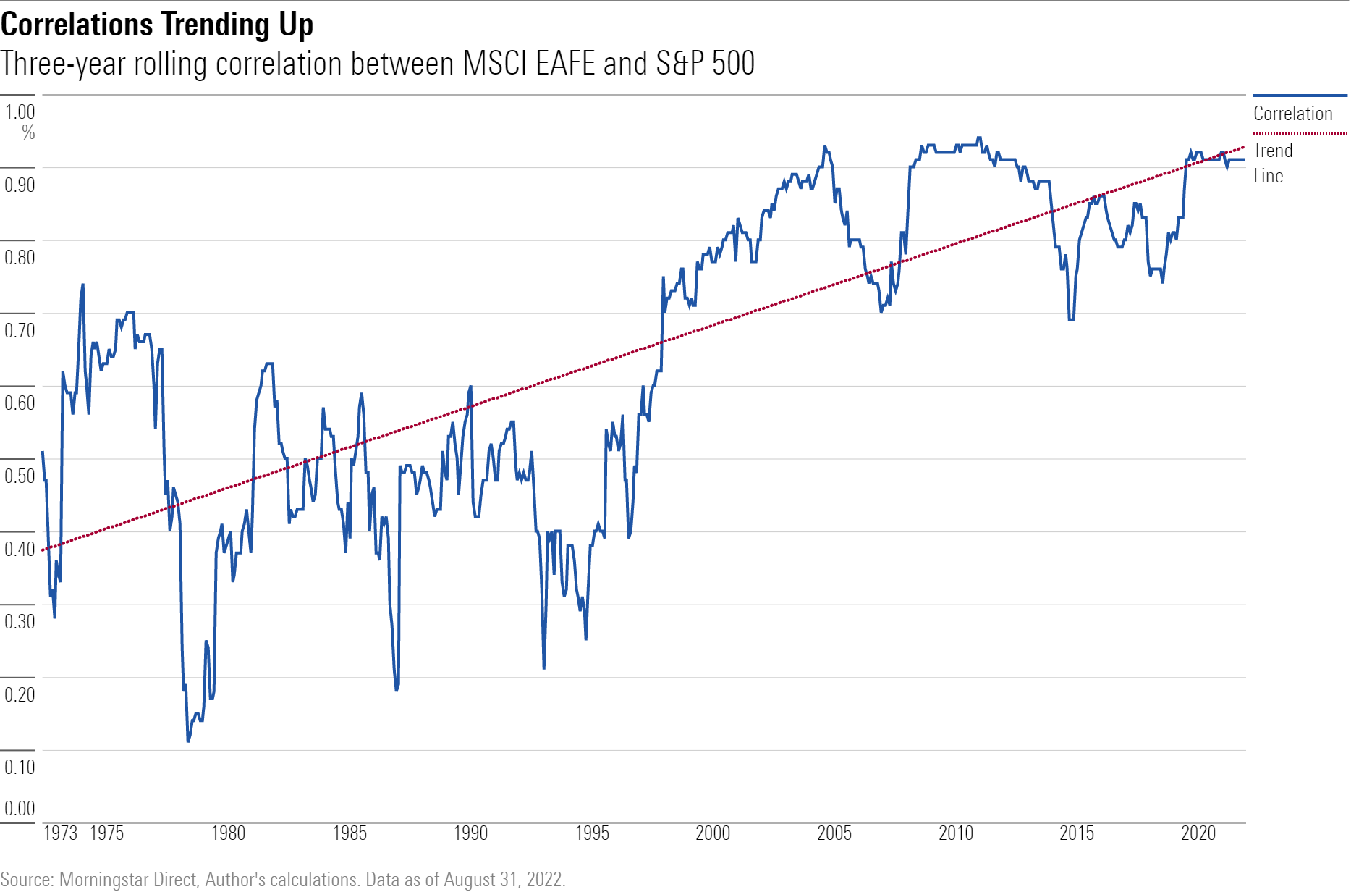

Perhaps most concerning of all, the correlations between the U.S. and global markets have been steadily increasing over time. That means the benefits of diversification—namely, risk reduction at the portfolio level and higher return per unit of risk—have also been eroding. In the past, the rolling three-year correlation between the S&P 500 and the MSCI EAFE Index has been as low as the low teens. Over the past few decades, correlations have gradually trended up. For the most recent three-year period, the rolling three-year correlation was close to peak levels, at 0.91.

That means that the benefits you'd hope to get from international diversification—the proverbial one asset class zigging when another one zags—just haven't happened. Instead, international stocks have generally moved in the same direction as large-cap domestic stocks. In the coronavirus-driven bear market in early 2020, for example, international stocks held up only slightly better than U.S. stocks, posting a loss of 33.3%, compared with 34.5%, respectively.

Granted, because the correlation between U.S. and international is still below 1.00, diversifying internationally still offers some risk-reduction benefits. But the benefits have been small. Over the trailing 30-year period through September 2022, adding a 35% stake in international issues to a domestic-equity portfolio would have reduced the monthly standard deviation to 14.31 from 14.47. But because non-U.S. returns fell behind over the same period, international diversification would not have improved risk-adjusted returns.

Conclusion

Despite these three issues, there are still valid reasons to invest overseas. Non-U.S. stocks make up more than 50% of the global stock market, so investors who limit their portfolios to domestic issues would exclude a large chunk of the investable market. And while currency movements and stronger earnings growth have favored U.S. stocks recently, that won’t always be the case. The steady increase in correlations is more worrisome, though. With stocks moving more in tandem globally, the benefits of international diversification aren’t as compelling as they once were.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MFL6LHZXFVFYFOAVQBMECBG6RM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EGA35LGTJFBVTDK3OCMQCHW7XQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)