Are Carbon Credits Ready for Their Close-Up?

We believe they have potential, but design flaws limit their current reach.

Energy markets attracted renewed attention in 2022 as gas prices and power bills skyrocketed. As the world reopened after coronavirus lockdowns, demand for fossil fuels surged. And acute oil and natural gas shortages have compelled countries to reconsider energy sources they once spurned, like nuclear power and coal.

Some of these developments will leave the climate-conscious feeling squeamish.

That’s one potential reason that interest in a little-known pocket of the financial system, called carbon markets, has also kicked up in recent months.

In our paper “2022 Carbon Credits Landscape,” we analyze the potential of these markets to price carbon and help reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

What Are Carbon Markets?

Carbon markets are nifty financial engineering, economists’ best stab at crafting a market-based solution to tackle climate change. They seek to price the future impact of today’s industrial emissions on our planet’s climate, shining a light on this hidden cost.

The concept is straightforward, but these units are tricky to value and exchange. Like the severity of climate change, the future cost to society of a ton of carbon dioxide is both unknowable and highly subjective.

There are two types of carbon markets: compliance and voluntary. Though their goals are the same—to price a ton of carbon— there’s a key difference in how the holders pay for carbon emissions.

- Compliance markets require companies in certain sectors to purchase permits in order to pollute, like expressway tolls. They’re often called “cap-and-trade” programs, because governments mandate that businesses in specified sectors keep carbon emissions under a particular ceiling, called a “cap.” Firms that pollute less than the government budgeted can “trade” their excess carbon on the open market.

- Voluntary markets function more like the indulgences of medieval Christianity, asking customers to pay retroactively for fossil fuels they have already torched in order to meet self-imposed targets.

These markets offer two different types of securities. The two are related but not the same.

- Carbon credits, which only trade on compliance markets, represent a holder’s right to emit one ton of carbon dioxide. Firms that want to pollute must purchase a carbon credit before emitting. They are created when another firm in the system pollutes less CO₂ than a regulator allows them to. This excess carbon is repackaged as a carbon credit and can then be traded on a compliance carbon market.

- Carbon offsets, which only trade on voluntary markets, allow companies and individuals to counteract carbon emissions after they have been released in the atmosphere. In order to offset historical emissions, carbon offsets actively reduce the amount of carbon currently in the system. The sale of offsets may bankroll renewable energy projects, which reduce future carbon emissions, or land-use projects, which strip carbon out of the atmosphere through things like reforestation.

Voluntary markets gain traction by convincing individuals and companies to take accountability for their emissions, and so far, they have grown at a consistent 45% clip.

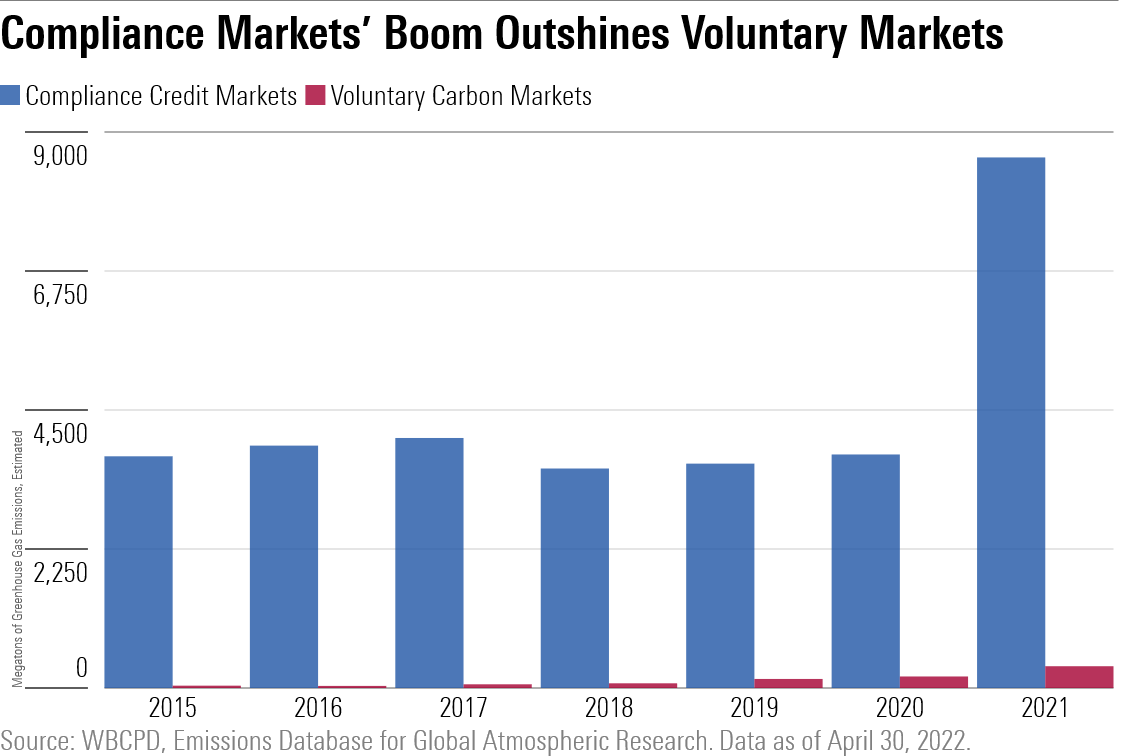

But building consensus is slow going. According to the World Bank, carbon offsets canceled out just 352 megatons of CO₂ equivalent in 2021. (We have stripped out carbon markets associated with the UN’s Kyoto Protocol, as those are not strictly voluntary.)

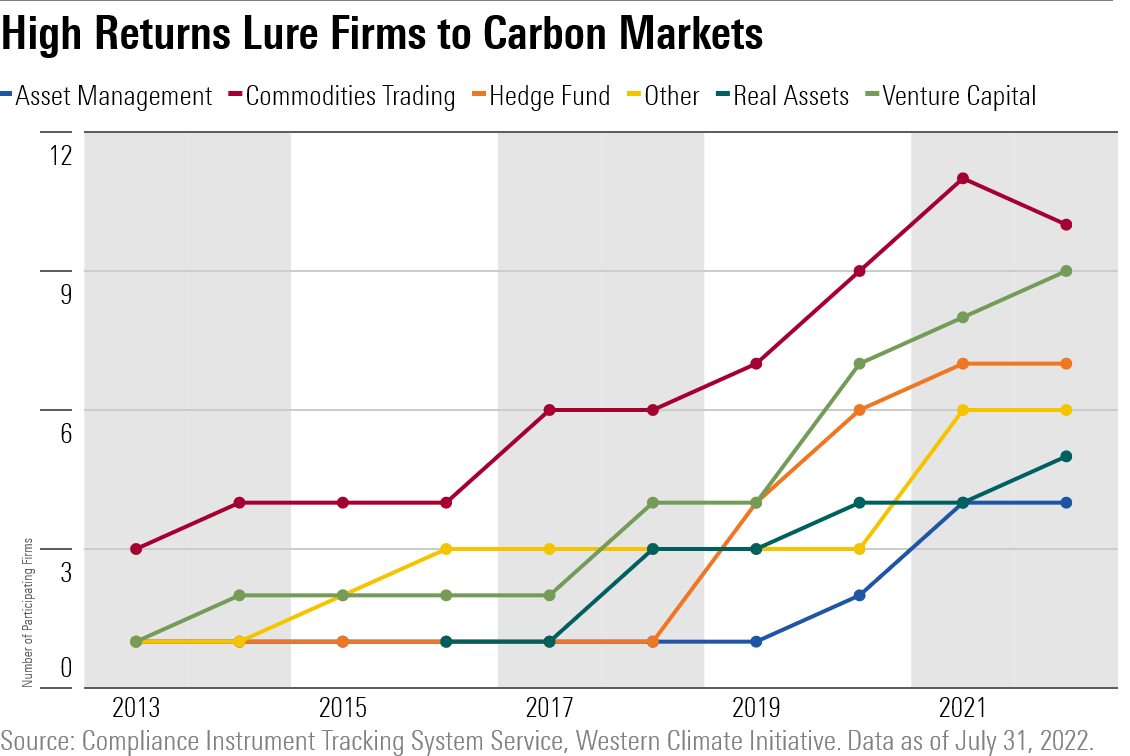

Meanwhile, compliance markets cover more than 8,590 megatons of CO₂ equivalents per year, making them the de facto pricing mechanism for carbon. Compliance markets, and the carbon credits that trade on these markets, enjoy the lion’s share of market depth and investor interest, as shown below.

As a result, we narrowed our focus to compliance markets for the rest of our analysis.

How We Assessed Carbon Markets

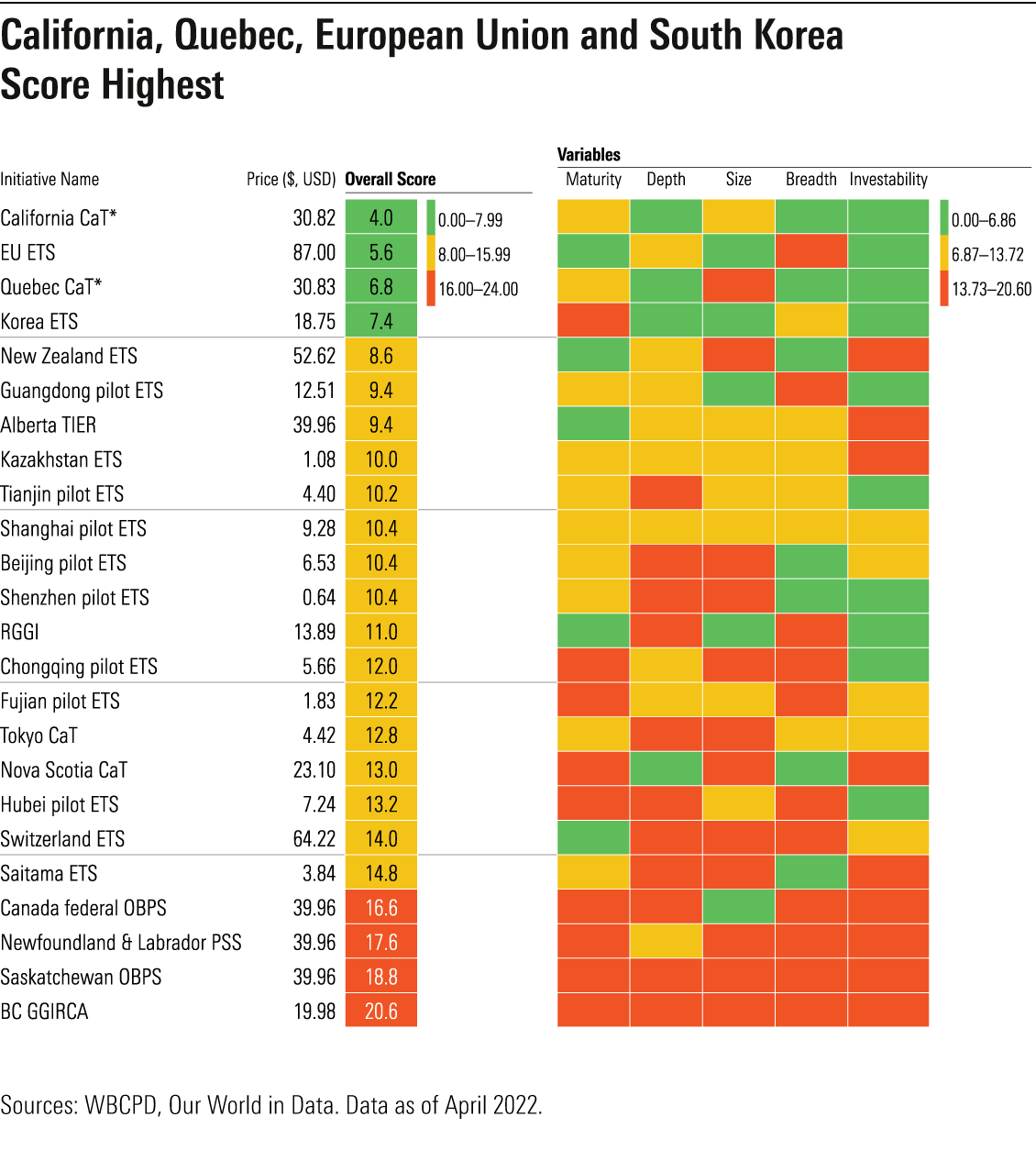

Because compliance carbon markets are highly variable and are difficult to compare with one another, we developed a five-pillar framework that assesses the following factors:

- Maturity

- Depth of emissions covered

- Size of market, based on total emissions within the jurisdiction

- Breadth of sectors covered

- Investability of assets

We then rated all nonoverlapping carbon markets that are more than three years old on this scale.

Four markets came out on top: California, the EU, Quebec, and South Korea. In our view, these four markets are the most representative and investable. That does not necessarily make these four the best or most effective—as we’ll discuss, efficacy can be measured in a variety of different ways.

Based on these results, we left some stalwarts out. Despite having a highly liquid and heavily traded futures market, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative of the eastern coast of North America missed out on inclusion based on a lack of breadth and depth in covered emissions.

Which Carbon Credits Programs Are Most Effective?

With this subset, we can dive deeper to determine whether these programs are effective.

The question is tricky to define because efficacy can be measured in several ways. Cap-and-trade programs have many use cases, including fostering innovation in climate technology and leveling the economic incentives between renewables and nonrenewables.

From our point of view, the most effective thing a cap-and-trade program can do on behalf of an investor is craft a price-discovery mechanism that makes carbon a comparable investment throughout time and across jurisdictions. Greater demand for carbon-intensive fossil fuels should usher in higher prices for carbon credits, acting as a drag on the economic incentives to pollute. This will discourage producers from investing capital in inefficient energy sources, and over time it should bring emissions within covered sectors to heel.

Today, carbon markets don’t create stable price signals--the relationship between fossil fuels and carbon credit prices is far too tenuous for that. This limits the desirability of the asset class for investors, not to mention for producers trying to forecast how much they need to reduce their carbon output. Ultimately, though, the absence of that effect does not determine whether these programs reduce emissions.

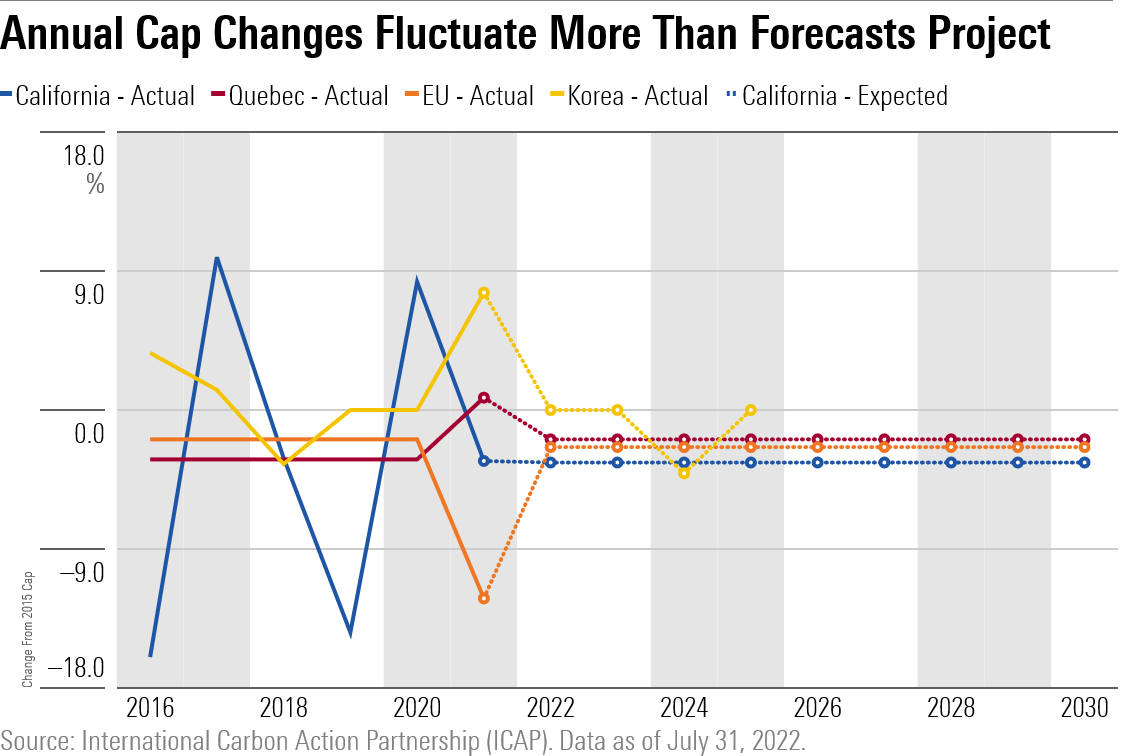

What really reduces emissions is a steadily declining cap. A strictly enforced ceiling on carbon emissions forces regulated industries to taper their carbon footprint or accept whatever premium carbon markets command. The problem is, as shown below, most caps are not very predictable.

A consistent pattern of past cap fluctuations indicates that future emissions caps are likely to taper at a lumpier pace than targets promise—if at all. This has ramifications for the health of carbon credit markets as a medium of financial exchange.

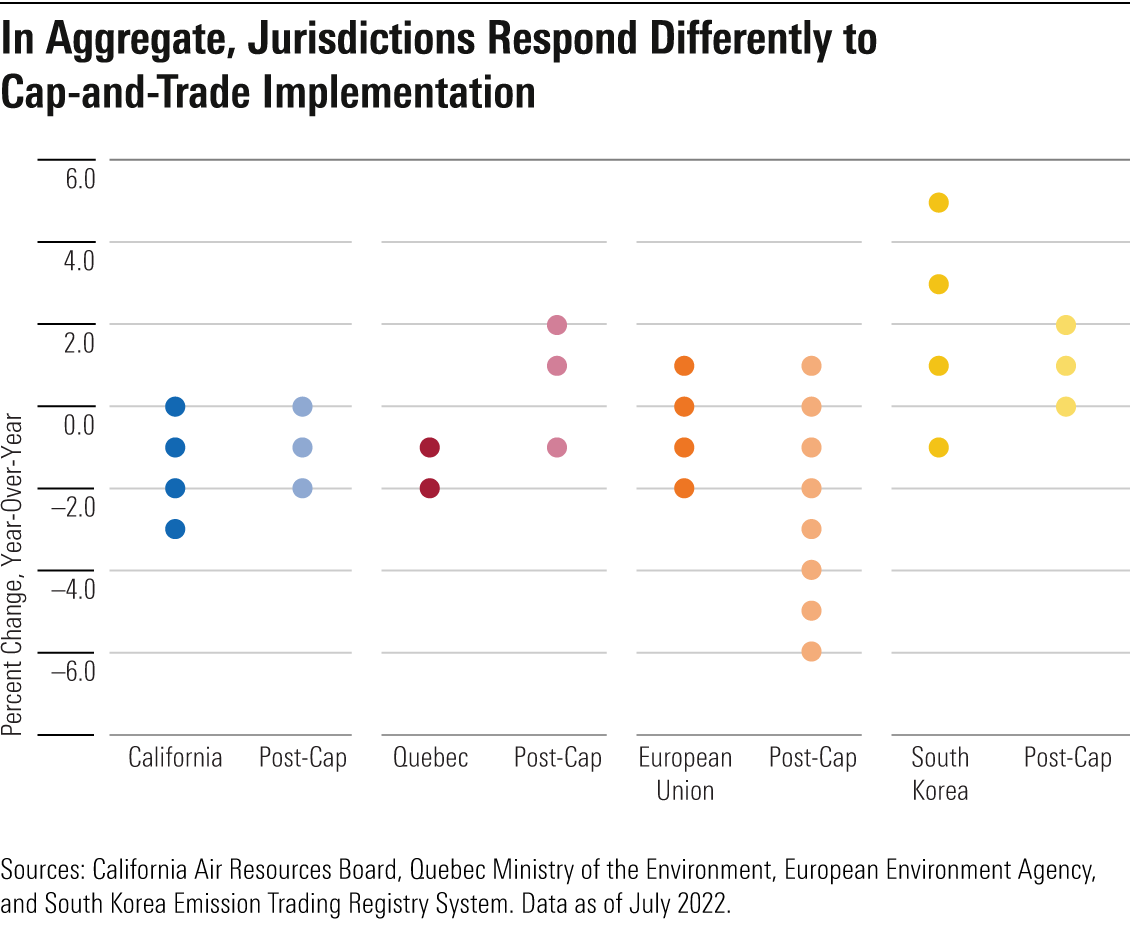

Methodological adjustments alter the supply of available credits and the rate of change year over year, making it more difficult for regulators—especially of immature programs—to exert consistent influence on the price of carbon or the contours of future emissions reductions. We believe that’s why, as shown below, only the EU has demonstrated clear success at reducing emissions in the sectors under its program’s coverage.

Can the Efficacy of Carbon Credits Programs Be Improved?

The good news is that program design is the major flaw of most emissions trading schemes, and it’s easily rectified.

Regulators can tweak existing systems to crack down on generous emissions caps and volatile prices--if they have the political appetite. The problem is that punitive systems, whether it’s a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade program, are broadly unpopular.

Besides being tricky to launch, the programs that survive put the governments that pass them into jeopardy. They are consistently at risk of getting replaced by those who promise to remove them.

Politicians are not likely to crank up the thermostat when they’re in the hot seat, which casts doubt on the potential of cap-and-trades to reach effective price levels in the future.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NNGJ3G4COBBN5NSKSKMWOVYSMA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6BCTH5O2DVGYHBA4UDPCFNXA7M.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EBTIDAIWWBBUZKXEEGCDYHQFDU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/eda620e2-f7a7-4aef-bb6c-3fb7f1ac7a38.jpg)