How Vanguard Came to Dominate the Fund Industry

It occupied the right competitive position at the right time.

Rise and Fall

Almost everybody knows the history of the video-rental industry. It began with VHS tapes hawked from cluttered, dusty mom-and-pop stores. The business was consolidated and scrubbed by a brash newcomer, Blockbuster, which then itself became outdated, thanks to the advent of streaming. Today, Blockbuster serves as a comic reminder of the 1990s, along with hammer pants and Cher Horowitz.

Much the same has occurred with mutual funds—minus the nostalgia. After spending their first 60 years as a cottage industry, funds vaulted to prominence during the 1980s as the properties of nationally recognized brokerage firms. Wherever there were televisions, there were advertisements for Merrill Lynch’s bull and Prudential-Bache’s rock. Pitchmen intoned, “Thank you, PaineWebber.” Even children knew those companies, and they all sold funds bearing their names.

But by the early 2000s it was clear, at least to the far-sighted, that those fund sponsors would share Blockbuster’s future. Believing that marketing muscle rather than investment results would ultimately decide their companies’ fates, they had neglected their products, which all too frequently had disappointed shareholders. As with the video-rental industry, the Internet was changing consumer habits, too. While many mutual fund investors continued to receive in-person advice, they were increasingly influenced by online sources.

(A third problem for the brokerage firms was that their employees learned to separate their personal fates from that of their corporations. When switching affiliations, better to have one’s clients in outside funds than to be forced to explain why some of the portfolio’s holdings had suddenly become unsuitable.)

Three Candidates

The kings were dead. Who would replace them? There were three viable candidates. Each boasted strong investment credentials, meaning that fund performance alone would not determine the outcome. Their relative success would instead by decided by business strategy. One of the three companies exceled in distribution, another in product variety, and a third in cost controls. The winning organization would be the one that possessed the attribute most highly valued by future shareholders.

1. American Funds—Distribution

The dominant supplier to financial advisors, American Funds was perfectly poised to capture business from brokers who no longer wished to sell house brands. The organization carried a limited product lineup of relatively cheap funds, all of them actively managed.

2. Fidelity—Product Variety

In 2002, Fidelity was the world’s largest mutual fund company, with a lineup to match. It managed 191 funds spread over 426 share classes. (In contrast, American Funds ran just 26 funds.) Its funds were moderately priced. Although almost all of them were actively run, Fidelity would launch index funds, if its customers so desired. The company was—and is—designed for one-stop shopping.

3. Vanguard—Cost Controls

Vanguard had arguably the industry’s most distinctive brand, known for being both the thriftiest provider and the leading indexer. Although Vanguard did offer an expansive lineup, including many actively run funds, the company’s fortunes depended upon the popularity of low-cost investing, especially index funds.

Vanguard’s Triumph

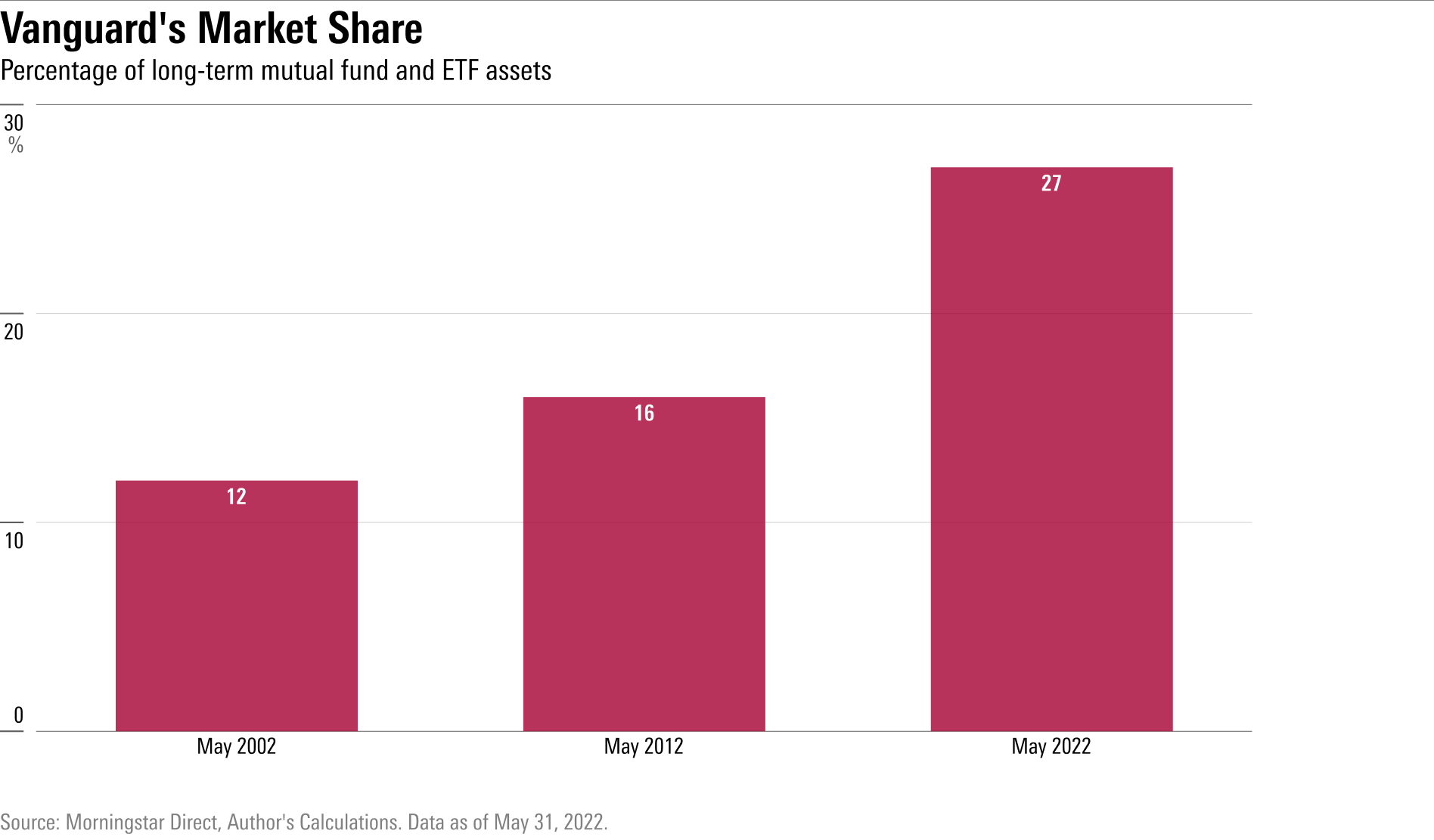

We all know how the story ended: Investors became far more cost-conscious, propelling Vanguard to victory. The margin of the company’s advantage is worth viewing, however. The following chart depicts the growth in the company’s domestic market share since 2002. Before Vanguard, no organization had ever controlled as much as 15% of the fund industry. That mark has been obliterated.

It should be noted that neither Fidelity nor American Funds flopped: Their investment results have been solid, if not quite up to their previous standards, and their shares of the market have not much changed. Thanks both to internal growth and to its purchase of Barclays Global Investors, BlackRock now occupies the industry’s second slot. But Fidelity is the third-biggest provider and American Funds the fourth, with fifth-place finisher State Street far behind each of them.

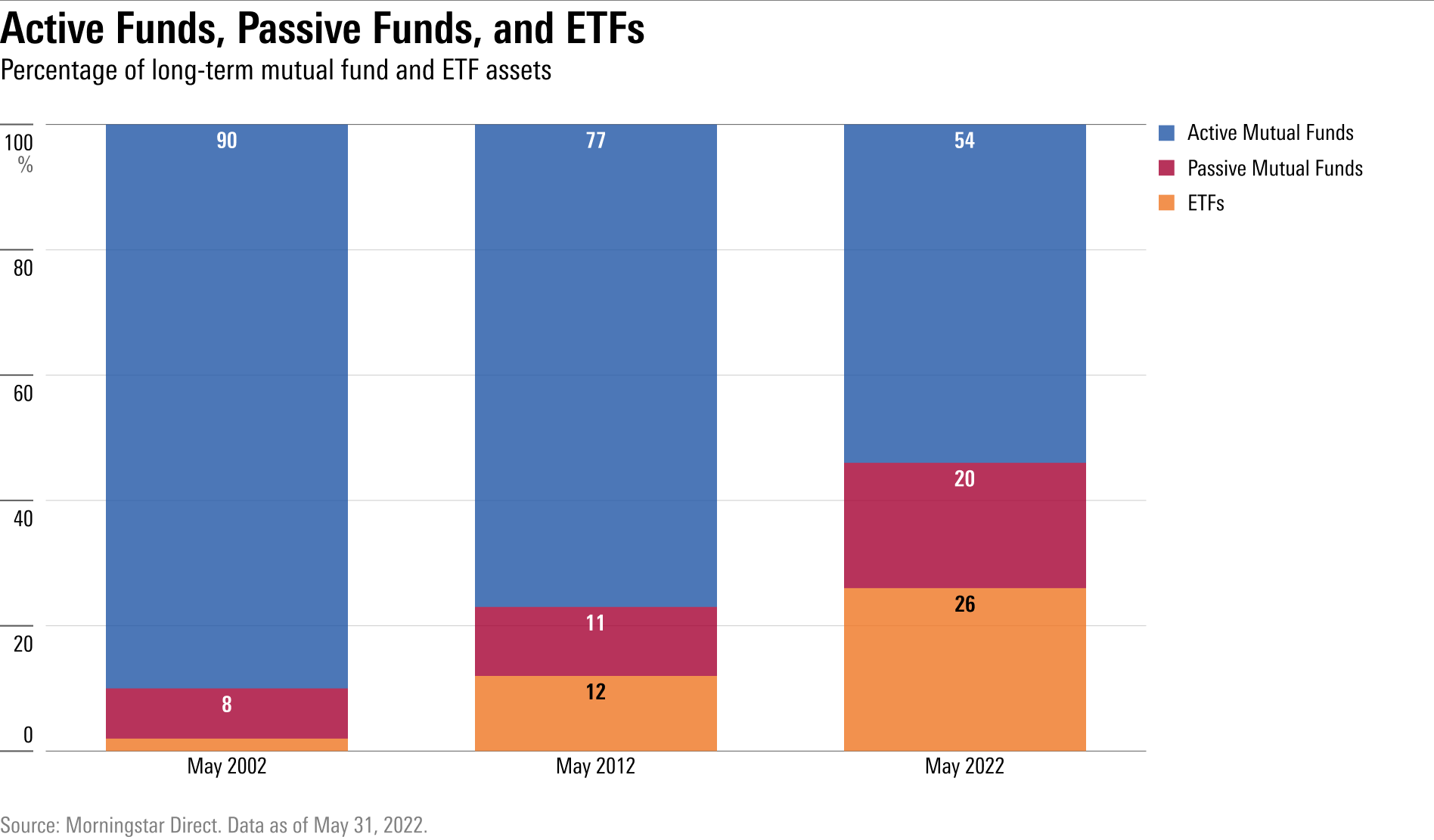

Vanguard moved far ahead of its rivals not because of its investment performances (which have been healthy) but rather because investors embraced Vanguard’s choices. Shareholders cared so deeply about costs that they moved index mutual funds into the mainstream. They also wholeheartedly embraced exchange-traded funds. Although Vanguard had not been an early adopter of ETFs, once it entered the field it became a major player almost immediately.

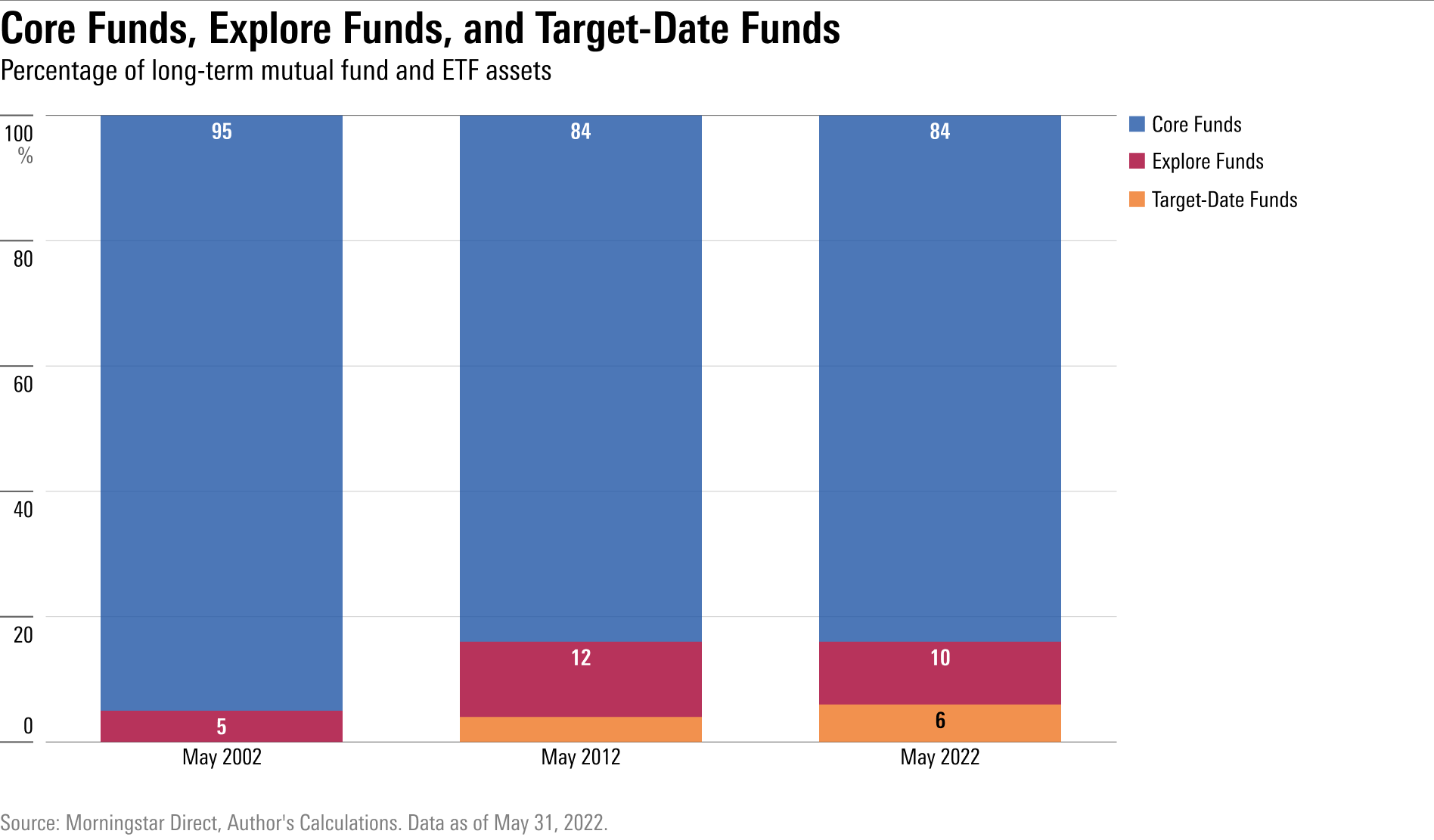

Also working in Vanguard’s favor has been the relative failure of fund-industry innovations. As with American Funds, Vanguard has historically emphasized the main investment courses. Other organizations pitched internet funds, or option-income funds, or nontraditional bond funds. Vanguard has preferred to sell cheaper versions of existing investment strategies rather than create new ones.

Adopting such a conservative strategy helps safeguard a company’s reputation, by protecting its shareholders from fads, but it runs the risk of being reactive. Had investment tastes changed substantially, Vanguard might have been left behind. However, aside from their wrappers, today’s funds are very much like those of 20 years ago. By my count, only 10% of the industry’s assets are in “explore” funds that invest unconventionally, such as liquid alternatives funds, commodities funds, or regional funds.

Looking Forward

Cost determined the winning fund company for this century’s first 25 years. I suspect that it will not do so for the next quarter of the century. The expense-ratio battle has mostly been played out; these days, most fund purchases go into funds that have little room to cut their costs further. The differentiating factor may instead be services. As with Fidelity (as well as Charles Schwab), Vanguard now seeks to be more than just an asset manager. Through various channels, including its Personal Advisor Services Group, it now dispenses financial advice.

Whether advice will indeed be the key differentiator remains to be seen. However, I do believe that the cost era is ending—not because it failed, but rather because it succeeded so spectacularly.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)