Are the Stocks of Stadium Sponsors Cursed?

Testing a widely held belief.

A Motley Crew

My coworkers recently joked about the fates of the companies that are presently sponsoring professional sports stadiums. Those businesses do not strike me as a promising bunch. The NBA, for example, has arenas named after crypto.com, Smoothie King, a Bahamian-based cryptocurrency exchange (FTX), and a materials-science company called Footprint, which succeeds forgettable America West Airlines, U.S. Airways, and Talking Stick Resort as the Phoenix Suns’ sponsor.

My colleagues are not the first to think along such lines. Twenty years ago, Enron and Conseco almost simultaneously became the largest and third-largest bankruptcies in United States history, each while having its name attached to a sports facility. (Conseco Fieldhouse for the Indiana Pacers, Enron Field for the Houston Astros). Those experiences, along with several other flops, have sparked a spate of articles bemoaning the stadium naming-rights curse.

Let’s examine the evidence. Admittedly, this effort will be only suggestive, not conclusive. Studying the topic properly would require not only compiling a database of all stadium names, past and current, but also calculating returns for companies that vanished from the stock market because they were acquired. With respect, gentle reader, such a study would be too much work for a single column published on a summer Friday before a 3-day weekend.

But we can still get a general sense of the matter. To that effort, I collected the sponsor names for all NFL, MLB, and NBA arenas in 2002. (I skipped the NHL, partially because as a California kid from the 1970s I know less than nothing about ice hockey, and partially because those facilities often overlap with NBA arenas.) I then attempted to assess how those firms have since performed.

Deadbeats and Dropouts

The list contained 36 companies. That was much smaller than the number of the leagues’ facilities, but many of the venues were either unsponsored (Fenway Park, Soldier Field, Madison Square Garden), or were supported by brands rather than corporate identities (Tropicana Field, RCA Dome).

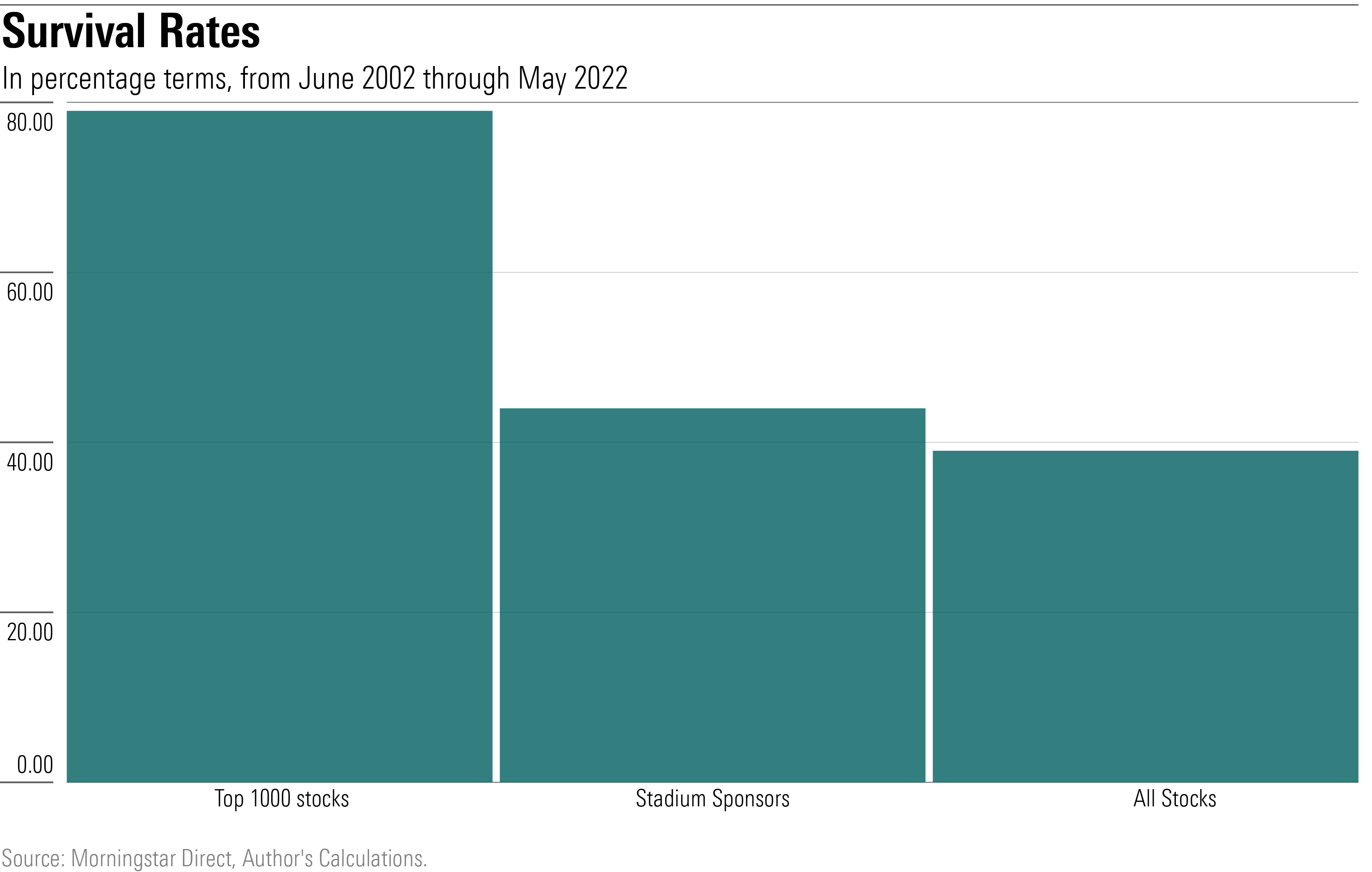

Of those 36 initial contestants, 20 companies have since disappeared, leaving 16 survivors. That seems like a high fatality rate. Then again, the overall stock market has rapid turnover. To reach a fuller perspective, I calculated the survival percentage over that same 20-year period, since June 2002, for two rival groups: the 1,000 largest U.S. stocks and the entire U.S. equity marketplace.

The stadium sponsors performed poorly. True, they were slightly likelier to endure than most stocks, but that is not much of a feat. Most publicly traded businesses are dandelions floating in the wind: here today, blown elsewhere tomorrow. (Apple’s market capitalization is 6,000 times that of the median-sized company in Morningstar’s U.S. equity database.) The true competition came from the largest 1,000 companies, which were far more persistent than the sponsors.

That said, the results for the expired sponsors were stronger than first appears. Most of their businesses remain intact. The bankruptcies, of course, attracted the headlines. But the various airline mergers–airlines being particularly fond of stadium sponsorship–did enrich shareholders. Most sponsors continued to grow their revenues, thereby attracting suitors. For example, Procter & Gamble snapped up Gillette, Molson Coors acquired Miller Brewing, and Verizon Communications bought Alltel. Those do not count as busts.

The Survivors

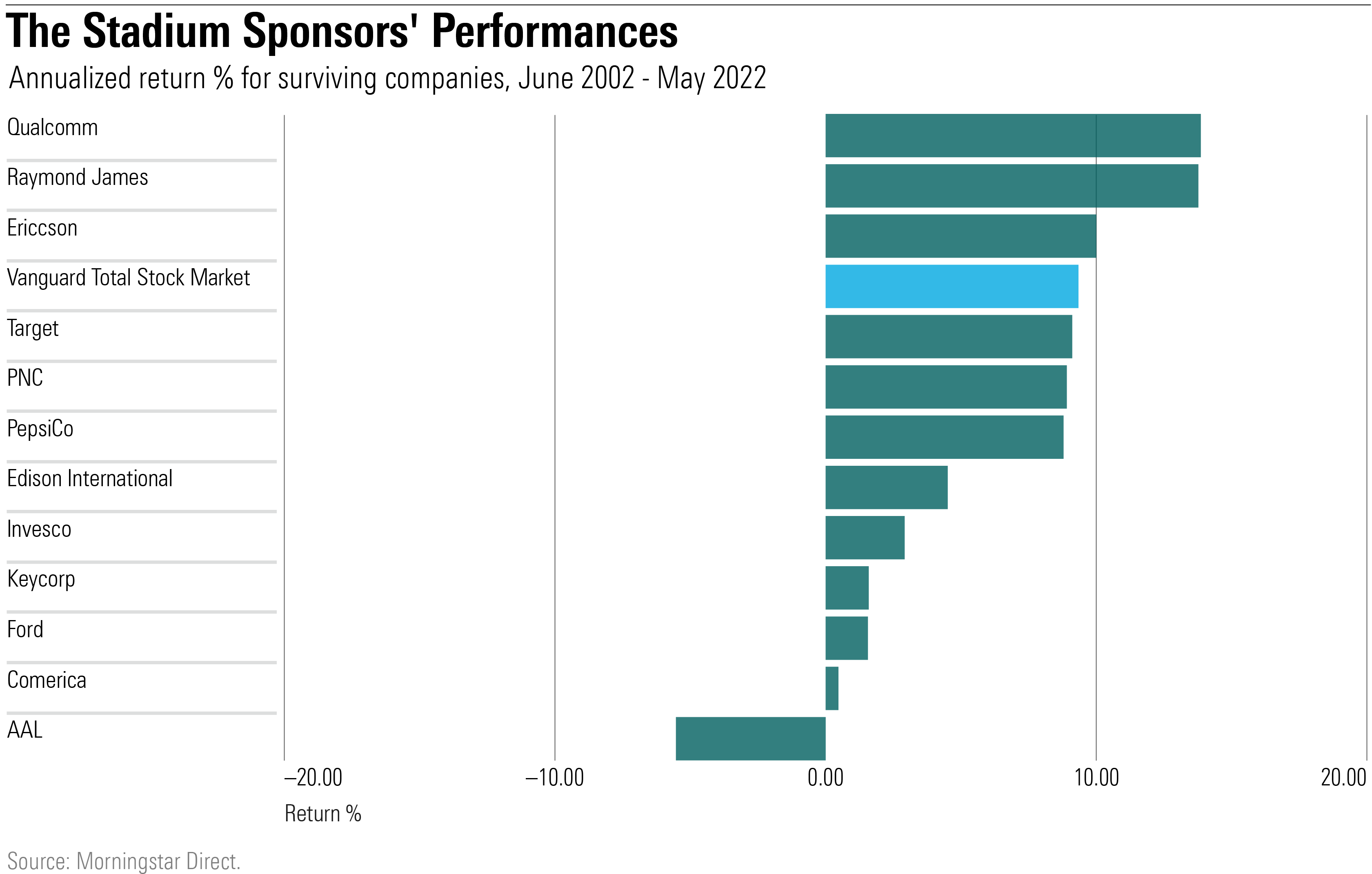

Of the delisted stocks, I can say no more, except they have fared better than the skeptics believe. But we can evaluate the performances of the surviving stocks. For technical reasons, I could not compute the returns for all 16 companies. However, I was able to locate trailing 20-year total returns for 12 of them, which I show below, along with the gain for Vanguard Total Stock Market Index.

As with the apparent outcome for the defunct stocks, the performance of the listed stocks has been better than advertised, but not great. Although stadium sponsorship was not a glaring contrarian signal, nor was it a positive sign. Too many sponsors have either occupied eroding industries, such as banks and airlines, or been on the bleeding edge of technology. Consequently, most of the stadium sponsors trailed the stock-market index.

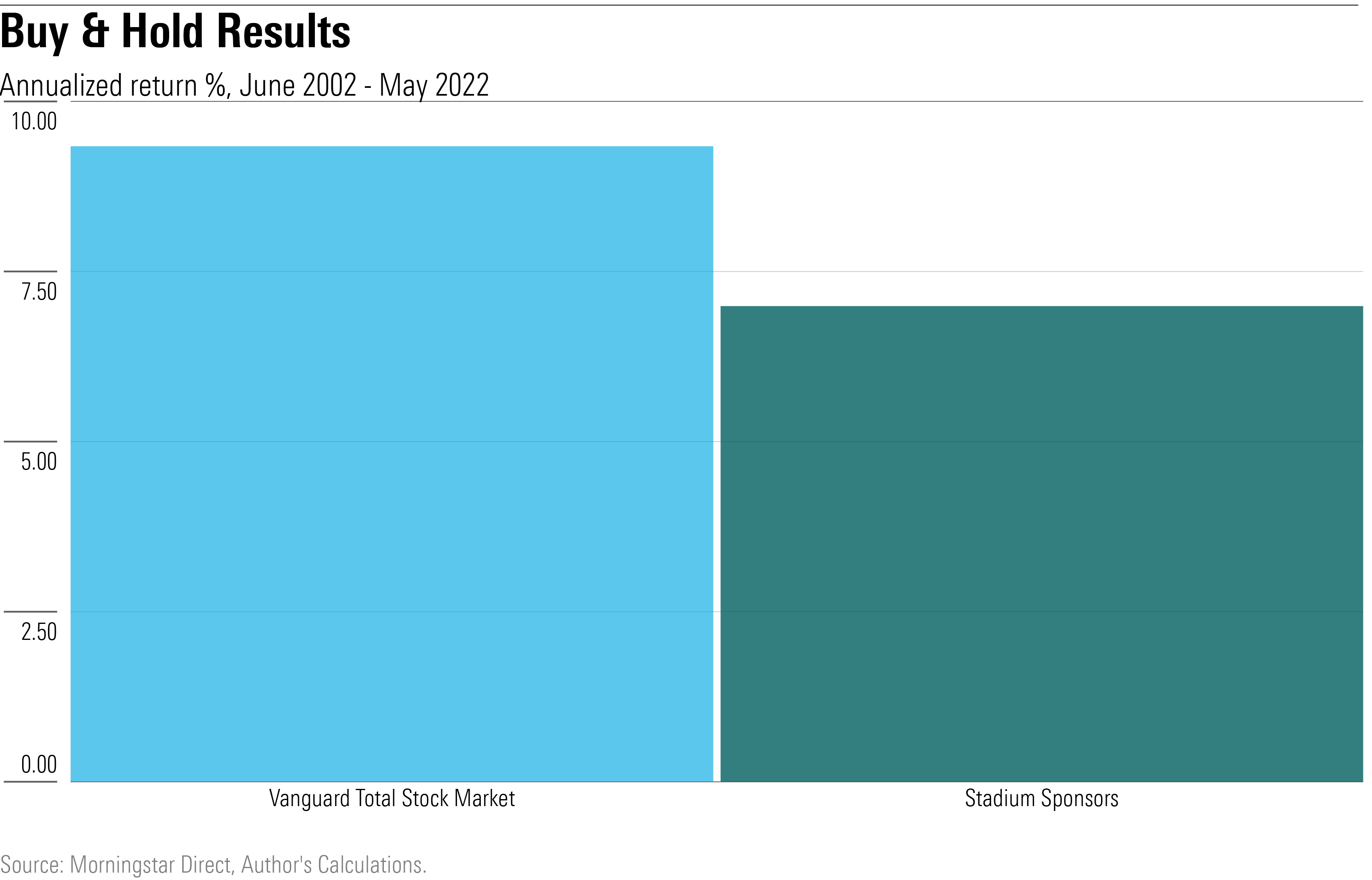

Another way of judging the contest is to compare a portfolio created from equal amounts of the stadium sponsors with that of a market index. The question then becomes, when to rebalance? One strategy is to avoid rebalancing entirely, by simply buying and holding each stock. Adopting that approach reaffirms the index fund’s superiority.

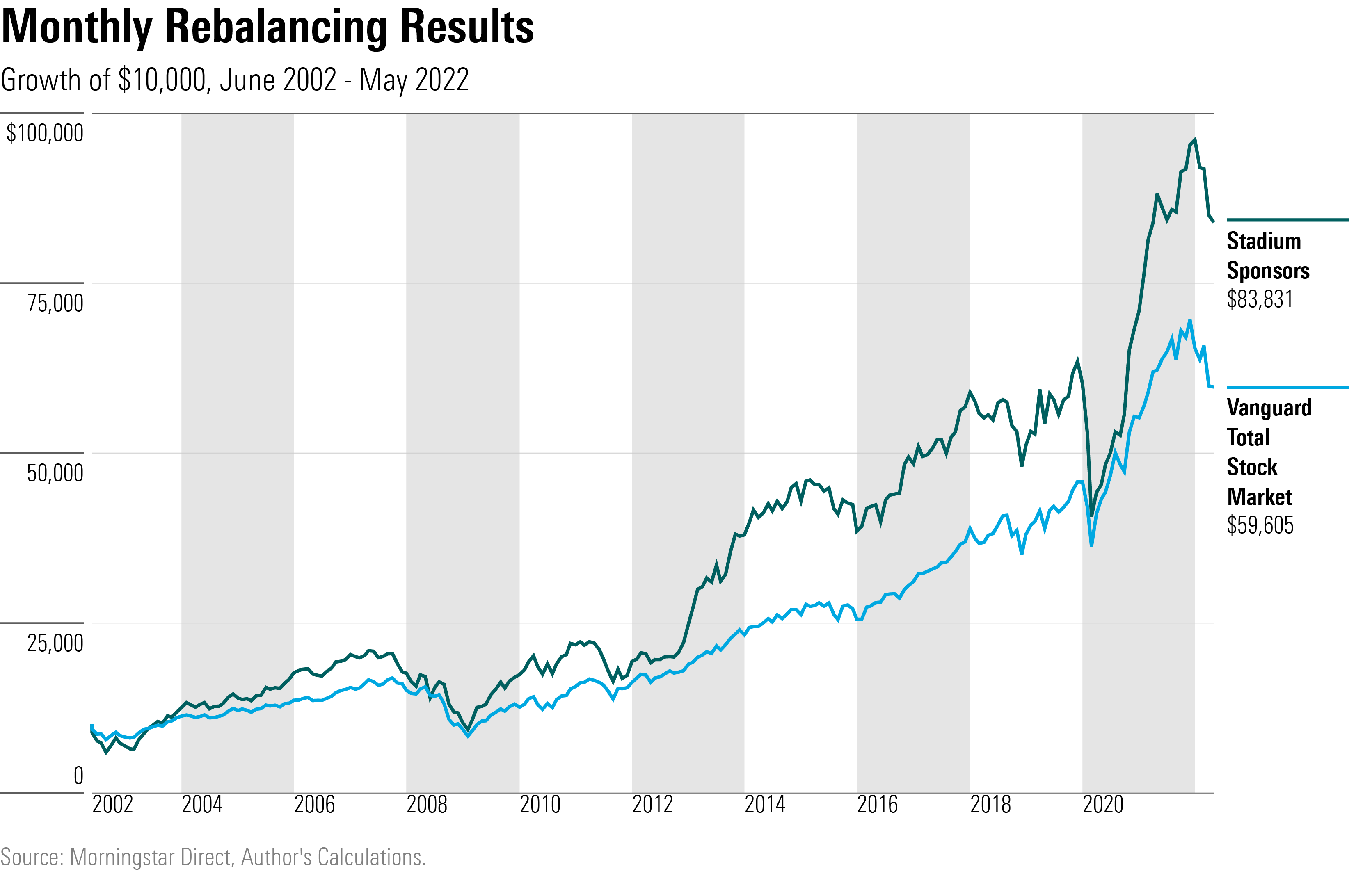

Conversely, one could rebalance the portfolio regularly, as with academic studies. (Real-life investors are rarely so rigorous.) I therefore tested a monthly rebalancing schedule. To my great surprise–so great that I rechecked the calculations several times–reforming the sponsor portfolio each month substantially increased its performance so that it handily beat the index.

Final Words

The result was something of a fluke. As it turned out, the stadium-sponsor stocks combined extremely well, leading to an unusually large rebalancing bonus. A happy accident. What’s more, although monthly rebalancing made the sponsor portfolio more profitable than the market index, it did not make for stronger risk-adjusted returns. As indicated by the severe gyrations in the green line, the stadium-sponsor portfolio was quite risky.

While I would hesitate to call stadium-sponsor stocks successful, given their high dropout rates and the fact that they required an unrealistically frequent rebalancing schedule to thrive, they have not been outright failures. The curse is a myth.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors own shares in one or more securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZZNBDLNQHFDQ7GTK5NKTVHJYWA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HE2XT5SV5ZBU5MOM6PPYWRIGP4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/AET2BGC3RFCFRD4YOXDBBVVYS4.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)