Why Target-Date Funds Became Conformist

The story behind this year’s results.

Twice Bitten

Participants rarely fuss about the performance of long-dated target-date funds. Shareholders tend to grant considerable leeway to investments that stipulate a 30-year time horizon. Besides, long-dated funds are owned by young employees, who typically pay little attention to their 401(k) plans. (About once per year, my son remembers that he has such an account, tucked away somewhere.)

Short-dated funds are a different matter. Most target-date 2025 owners have either already retired, or they will soon do so. No longer will human capital pay their bills. They must turn instead to their financial capital. The poor possess few 401(k) assets, and the wealthy do not require them. For the great many who land in the middle, though, those 401(k) balances become critically important.

It therefore came as no shock when severe investment losses during the 2008 global financial crisis sparked biting criticism, including a Senate inquiry. Eventually, the fund industry escaped with nothing worse than admonitions, but stronger measures were debated, including regulations on how target-date funds could invest.

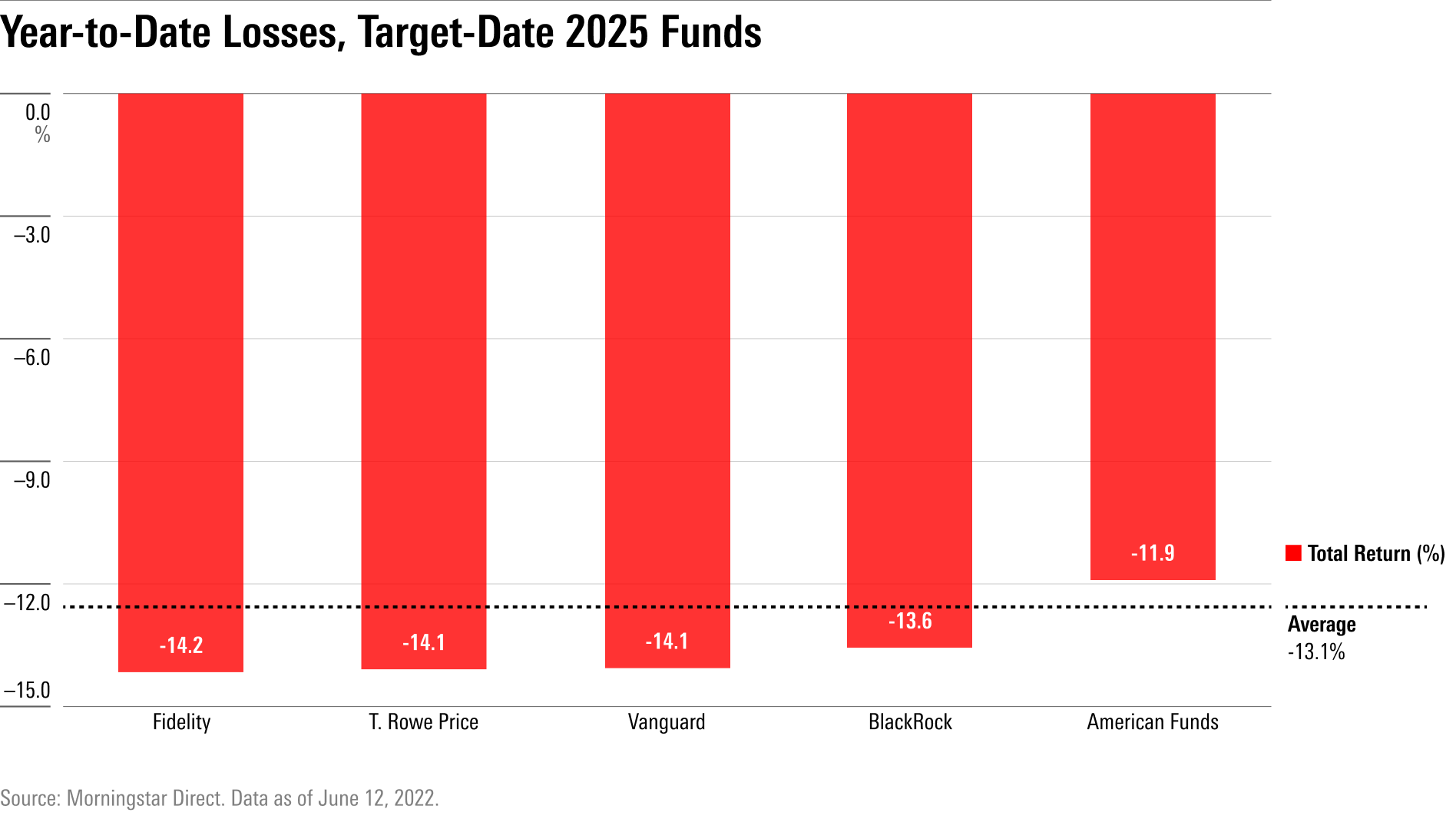

Although losses among short-dated target date funds have been less dire than 2008′s 22% downturn, they are rapidly heading in that direction. Through this past Friday, the target-date 2025 Morningstar Category had dropped 13% for the year to date—a shortfall that will increase when Monday’s losses are included.

Moving in Lockstep

Returns for the five largest target-date 2025 funds, which collectively account for 80% of the category’s assets, have been almost identical.

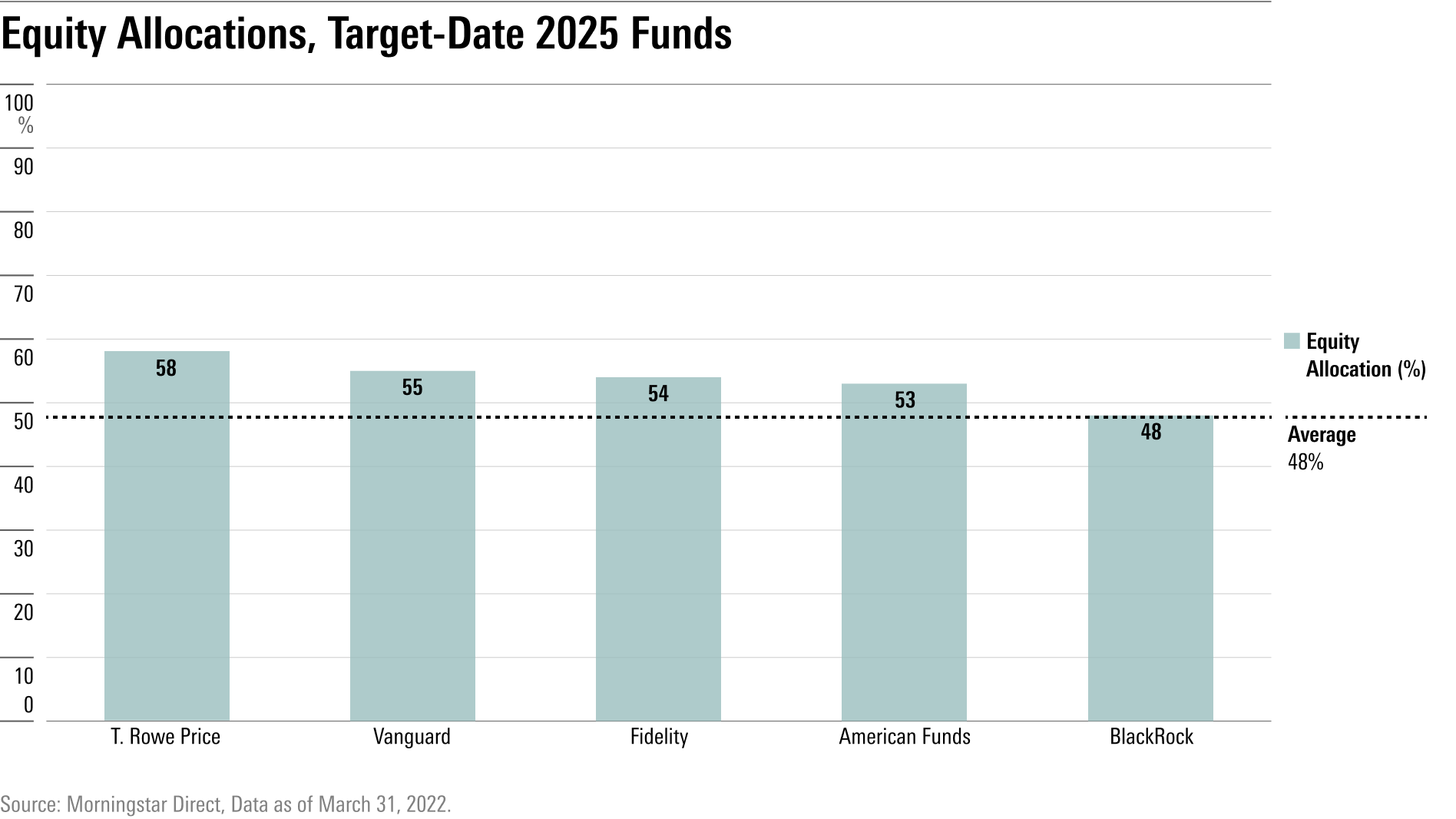

As the performances suggest, the biggest target-date 2025 funds invest similarly. Each fund places about half its assets in stocks, with international securities accounting for 30% (American Funds) to 50% (Fidelity) of that allocation. Each fund also puts most remaining monies into bonds, keeping cash at a 5% to 10% position, with the bonds also diversified internationally, although generally not as heavily as with the funds’ equities. (True, two of the funds, those from Vanguard and BlackRock BLK, are indexed, while the other three are actively managed, but that detail is immaterial when explaining short-term returns.)

That the major families are all alike is understandable. As previously mentioned, target-date funds live under a microscope. True, their shareholders consider absolute rather than relative performances, because they cannot buy rival funds. One 401(k) plan, one target-date series. But those who sponsor 401(k) plans can shop elsewhere—as can the financial advisors and consultants who serve them. They therefore ask many questions of target-date families that trail their competitors.

To vs. Through

This scrutiny has pushed the leading fund families toward conformity. In the early days of target-date funds, some series were managed to the target date, while others were managed through it. The former slashed their equity allocations as that date approached, while the latter merely tapered. Their managers argued that the stated target date was arbitrary. Most shareholders, after all, would live for many more years. They therefore needed meaningful equity exposure.

Among large providers, that debate has been settled. The biggest target-date series have become T. Rowe Price TROW. Once regarded as extreme, owing to its funds’ high stock exposures, T. Rowe’s strategy is now thoroughly mainstream. Some smaller providers have abstained—for example, Putnam and John Hancock offer target-date 2025 funds that invest less than 30% of their proceeds in equities—but collectively, they account for only 3% of the category’s assets.

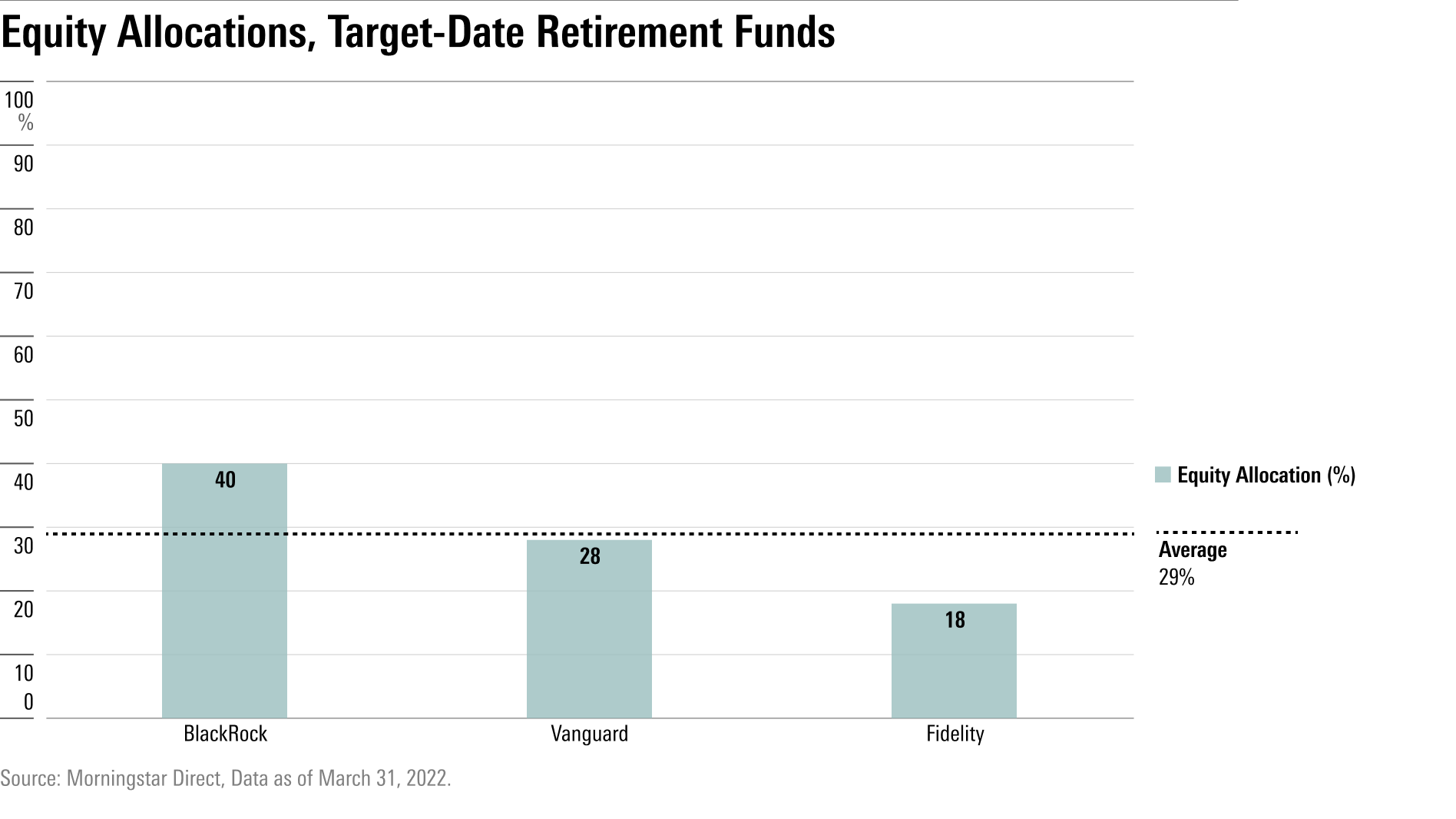

After the retirement date, the conformity among target-date series ceases, as both the marketing and investment approaches diverge widely. Some fund companies manage their target-date funds well past the initial date. For example, 34 target-date 2015 funds continue to exist. Other companies shutter such funds, dropping their assets into funds that are typically called (and are categorized by Morningstar as) “target-date retirement” vehicles. The equity allocations among such funds vary widely.

Birds of a Feather

Joining the “through” crowd has not only protected the leading funds from receiving awkward questions about their relative performances, but it has also made for higher long-term returns. Despite this year’s troubles, four of the five largest target-date 2025 funds have outgained the category average over the trailing 10 years, with BlackRock’s fund being the lone exception.

However, as this year’s results have demonstrated, few benefits come without a catch. Because the largest fund families invest similarly, target-date 2025 funds have given their shareholders little chance of escaping this year’s carnage. That outcome is ironic. Following their 2008 losses, target-date funds sought to avoid investment restrictions imposed by politicians. They dodged that possibility, but then found themselves similarly constrained by the marketplace’s demands.

Wrapping Up

Target-date funds often face capricious attacks. Consider, for example, a complaint that I recently investigated, that target-date funds hold too many international stocks. A reader responded by noting how another target-date skeptic, Paul Merriman, wrote the direct opposite, stating that “Target-date retirement funds are heavy on large-cap U.S. stocks and very skimpy on small-cap stocks, value stocks, international stocks, and real estate.”

One gets the sense that target-date fund’s critics begin with the conclusion that target-date funds are flawed, then find the reasons why. If the witch drowns, she is innocent. If she floats, she is guilty and must be burned at the stake.

With this column, I wish neither to bury Caesar, nor to praise him. There are legitimate reasons why the largest target-date fund providers have adopted “through” investment policies. In addition, there is something to be said for fund-company conformity. Shareholders usually are pleased when their funds deliver no surprises. However, equity bear markets are very much the exception—and the major short-dated target-date funds are not well positioned to weather them.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/O26WRUD25T72CBHU6ONJ676P24.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)