Vanguard Case Study: How Much Bang Does Style Rebalancing Provide?

Here’s what we learned after running the numbers.

The Question

Tuesday’s column discussed how Vanguard Growth Index and Vanguard Value Index, the company’s first “strategic-beta” funds—that is, funds that slice broad indexes into smaller and presumably superior pieces, known as investment “styles”—perturbed the company’s founder, Jack Bogle. He worried that investors would end up chasing their tails by buying the hottest recent performer. As Tuesday’s article showed, Bogle’s concern was initially well founded, but investors have since avoided that problem.

In response, a reader wrote, “I was waiting for you to discuss the supposed ‘free lunch’ of rebalancing over the long term. I’ve always thought that the main benefit of breaking the S&P 500 into subsets was to be able to rebalance the pieces over time rather than to guess which piece would win. Any thoughts on whether an investor who rebalanced those two funds (say annually) did better than his brother who purchased the whole S&P 500 and then headed for the beach?”

That is a topic worth investigating. Twice during the fund’s histories, growth and value stocks have very much gone their separate ways. (The first instance was from the late ‘90s through 2001, and the second from 2019 onward.) Those appear to have been golden opportunities for rebalancing, which is pointless when investments perform similarly but often useful when they diverge.

Buying and Holding

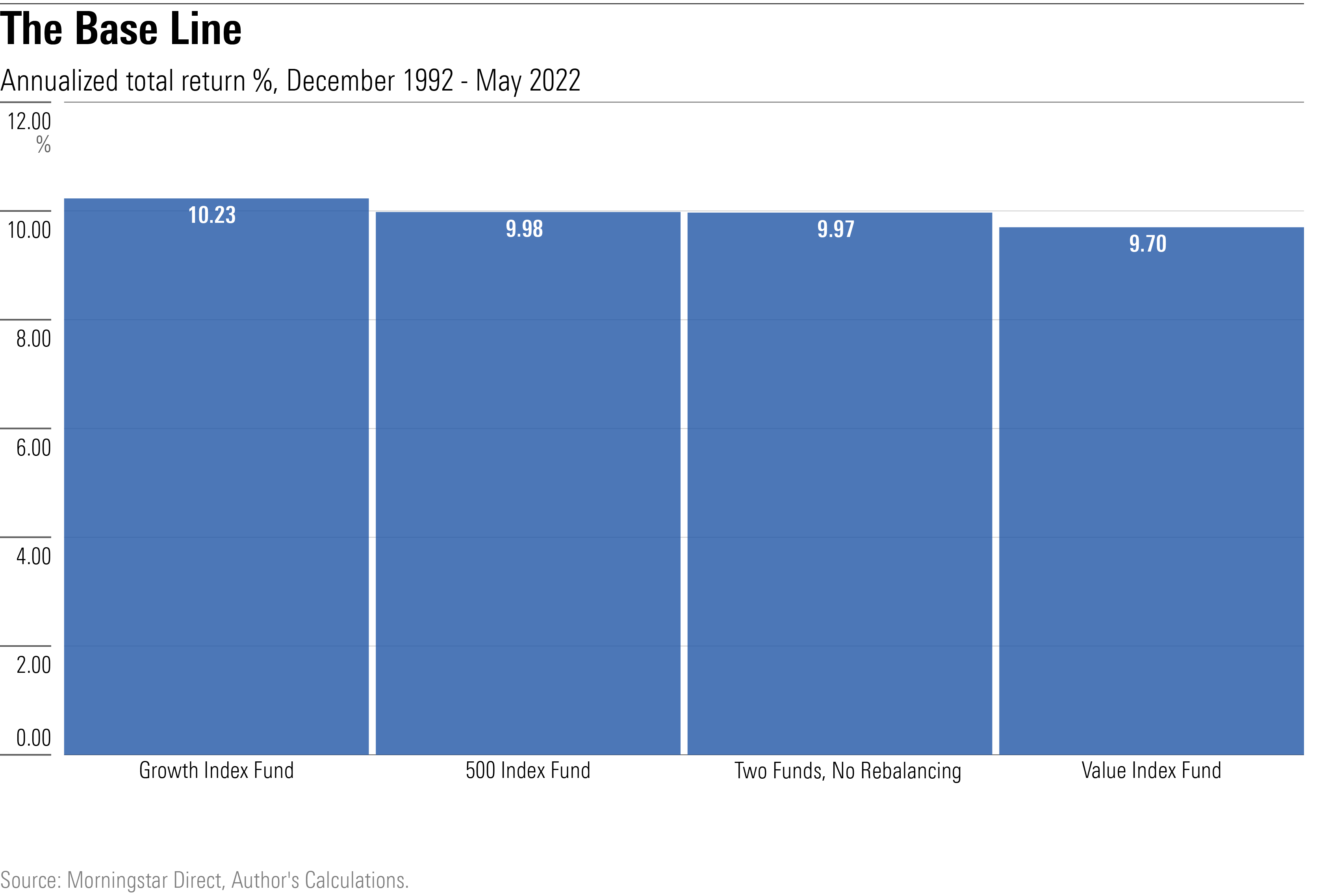

That observation pretty much exhausted my insight; intuition carried me no further. Time to run the numbers. My starting point was the performances for the Growth and Value Index funds since their inceptions, along with that of the fund from which they were carved, the Vanguard 500 Index. I also calculated the return for a portfolio that divided its initial investment between the Growth and Value Index funds, then never rebalanced.

As one would have expected, the 500 Index Fund landed almost smack-dab in the middle between its two constituents. (Actually, the Growth and Value Index funds now derive from a different fund, Vanguard Large Cap Index, because Vanguard rejiggered the formula many years ago, but never mind that.) So, too, did the two-fund portfolio that was never rebalanced.

This exercise provided the baseline for assessing the advantage (or not) of rebalancing. The 500 Index Fund has returned 9.98% annually, while the two-fund portfolio of the Growth Index and Value Index funds has performed almost identically, at 9.97%. Those would have been the results for the reader’s brother, who bought his fund(s) and then headed for the beach. Would his sister, who regularly rebalanced, have been rewarded for her greater diligence?

Rebalancing

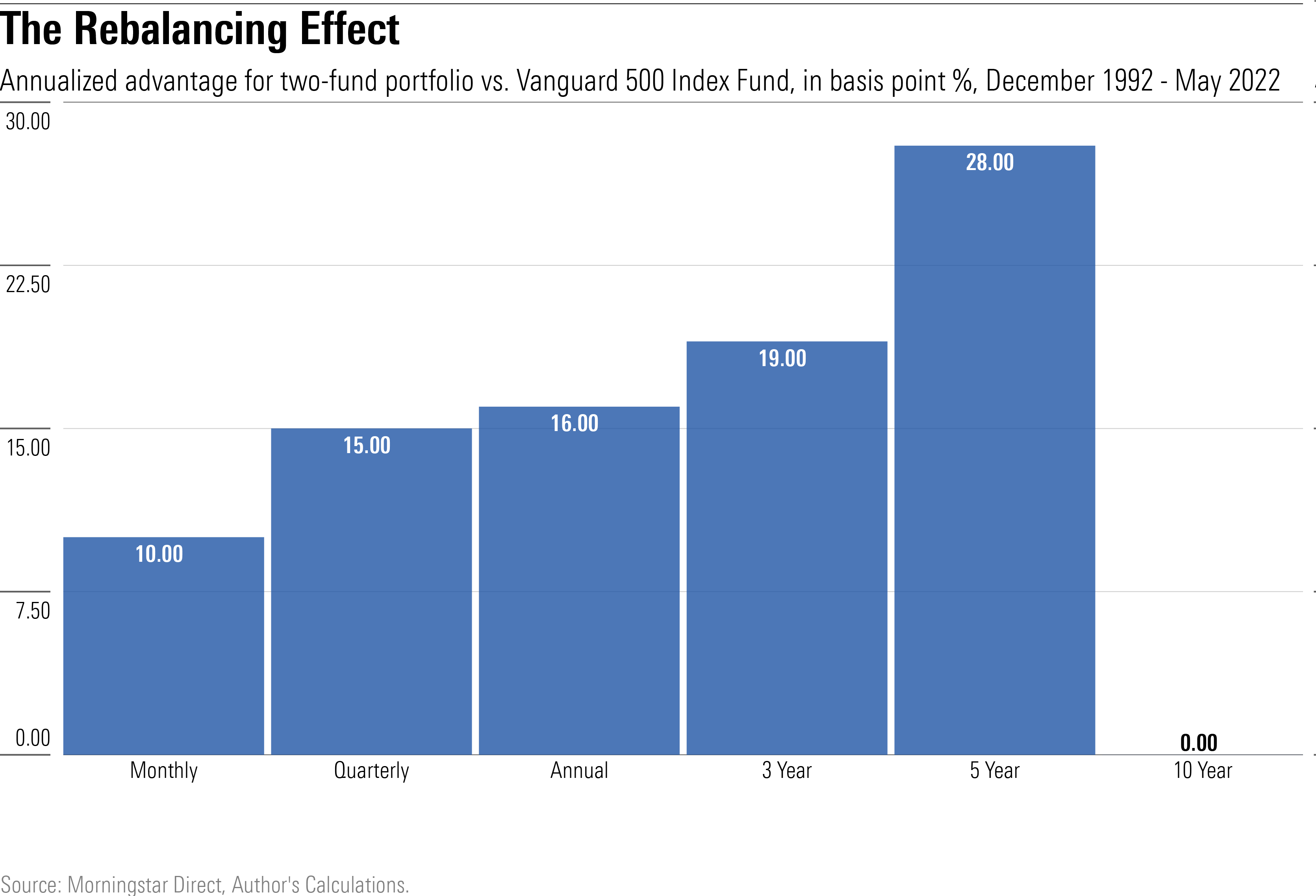

The answer, of course, will vary according to the rebalancing schedule. Finance professors typically reconstitute their portfolios monthly. Fund investors, presumably, will not wish to be so active. Nevertheless, at least for theoretical reasons, we can evaluate the monthly strategy. Other possibilities include quarterly, annually, every three years, and every five years. Finally, out of curiosity, I tested how rebalancing once per decade would have fared.

My approach in all cases was identical. Begin the study in December 1992, which was the first full month that the Growth and Value Index funds existed, then rebalance from that date onward. For example, reconstitutions for the annual schedule occur each Nov. 30. In contrast, the 10-year schedule makes only two trades, one at the end of November 2002, and the other a decade later.

The following chart shows the outcomes for each rebalancing schedule. The numbers represent annualized basis points, when compared with Vanguard 500 Index’s performance. Thus, the figure of “10″ that appears for the monthly rebalancing schedule indicates that if the Growth Index and Value Index funds were purchased in equal amounts, and thereafter rebalanced monthly, that portfolio would have returned 10.08%, as opposed to the 500 Index’s 9.98% gain.

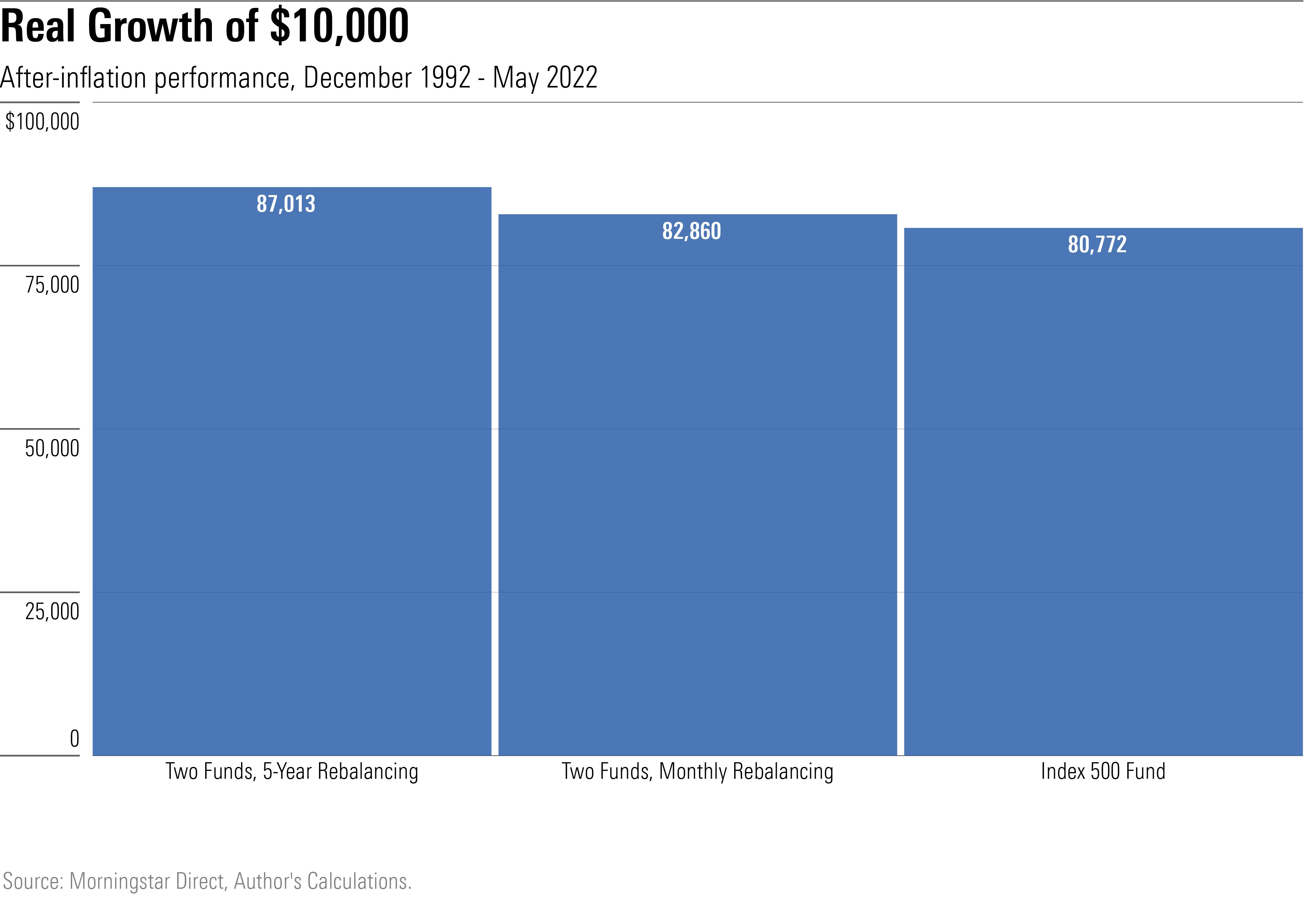

The improvements are meaningful. As indicated by the fierce index-fund price wars, many investors swayed by discrepancies of 2 or 3 basis points. That don’t impress me much. Even after several decades of compounding, such amounts have little effect on investment outcomes. Not so, however, from rebalancing Growth and Value Index funds. Consider, for example, the since-inception totals for the 500 Index Fund vs. the two-fund portfolio, when the latter is rebalanced every five years.

(Note: These totals are presented in after-inflation terms. The differences in nominal returns are larger yet.)

The Upshot

As both Vanguard and Jack Bogle have acknowledged, there is no single correct response to the question, “Should I rebalance?” If one investment is better than another, rebalancing is probably unwise (as was buying the weaker investment in the first place). If, on the other hand, the two securities are of similar quality but one has both higher returns and greater volatility, then rebalancing cuts both ways. Doing so reduces the portfolio’s risk—but also its expected total returns.

In other words, the lunch from rebalancing assets with different risk levels, such as stocks and bonds, may be tasty, but it does not come for free. As two AQR Capital Management researchers have pointed out, though, rebalancing does provide a free meal if the technique is used with two investments that have similar risks and that arrive at the same destination, while taking different paths. (In such cases, the authors note, the relative performances of each investment must necessarily revert to the mean, thereby rewarding the rebalancing strategy.)

That neatly describes the behavior of the Growth and Value Index funds. Consequently, if investors are to rebalance, doing so with Vanguard’s Growth and Value Index funds—or other funds that have been created in similar fashion, by dividing a broad stock market benchmark—would seem to make unusually good sense. The conditions favor rebalancing style-based equity portfolios.

Whether five years will remain the ideal rebalancing schedule remains to be seen. That will depend on the details of the funds’ performances. But I suspect that longer rebalancing schedules, to ride protracted swings in the relative prices of growth and value stocks, will remain the most successful. Perhaps three years?

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CGEMAKSOGVCKBCSH32YM7X5FWI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/LUIUEVKYO2PKAIBSSAUSBVZXHI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)