Nobody Likes Index Funds, Except Investors

The three-pronged attack on index providers.

In the Spotlight

The two best mutual fund inventions are also the two fund innovations that have been most heavily criticized. Or course, there is good reason for the connection. Success brings scrutiny. Only their makers cared that 130/30 funds flopped. Such funds never became important enough to earn attention.

Not so for target-date series. At $1.5 trillion in assets, while serving as the mainstay of 401(k) plans, target-date funds have, well, become targets. Recent headlines have alleged four reasons why investors should avoid target-date funds. Also these four, and five more drawbacks. (Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition.) Never mind the details: Their point is that target-date funds are simply a terrible choice for most investors.

Well now. Over the past five years, target-date 2030 funds—to name one example— have outgained both the average balanced fund (cumbersomely if accurately called allocation–50% to 70% equity funds by Morningstar) and the typical hedge fund, as measured by the HFRI 500 Investable Hedge Fund Index. If that performance is a lemon, most investors will happily drink lemonade.

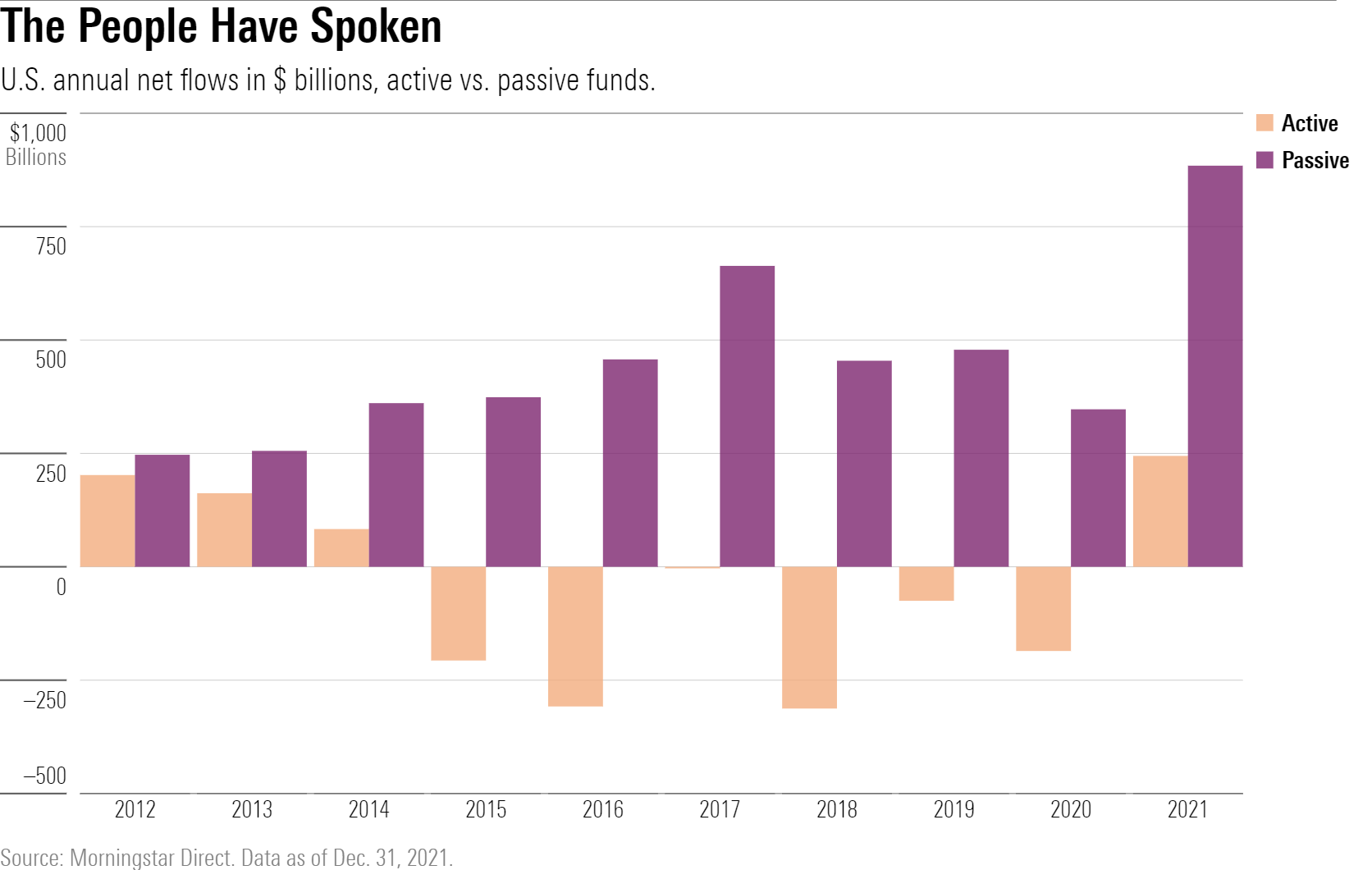

At least the objections to target-date funds have been confined to the financial section, aside from one hearing by a Senate subcommittee. Meanwhile, index providers have been torched on the general pages. Because they control $11 trillion in mutual fund and exchange-traded fund assets, rather than the $1.5 trillion that target-date funds possess, index funds have become that much more visible. Their recent sales figures have not escaped notice, either.

Consequently, index providers have reached the mainstream news—and the reviews have not always been kind. A prominent example occurred earlier this month in the Opinion section of The New York Times, with "What BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street Are Doing to the Economy." As you might suspect from the headline's tone, the author's answer was "bad things."

The Left Speaks

His critique came from the left. Because index-fund providers have "common ownership," meaning that their funds hold multiple companies within each industry, they presumably dislike competition. If Coca-Cola KO and PepsiCo PEP slash their prices, in the attempt to gain market share, both companies won't win. In fact, if the battle is sufficiently brutal, neither of them will. On the other hand, each company can thrive by accepting the status quo and keeping prices high.

In short, per this analysis, index-fund providers are soft on corporate executives. Rather than push CEOs to excel, in a fight that should be red in tooth and claw, index-fund providers signal, through nods and winks, that their companies should play nice in the sandbox. Gradually, American industries are resembling cartels. Such behavior leads to economic inefficiency. Prices are higher than they would be under perfect competition, output is lower, and innovation is suppressed.

Then the Right

The article also contained criticism from the right. When researching the topic, the author contacted a technology entrepreneur who has published a book entitled, Woke, Inc.: Inside Corporate America's Social Justice Scam. (When I stated that he was from the right, I wasn't kidding.) He also objects to indexing, but while making the opposite claim. Index providers fail not because they bolster corporate profits, but instead because they stymie them.

The reason being that index providers support "liberal political positions" by advocating for environmental, social, and governance principles. Potentially, these admonitions may cause companies to neglect their fiduciary duties. Along the same lines, two Republican Senators, Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania and Dan Sullivan of Alaska, have introduced a bill that would give index-fund shareholders voting rights, so that they could overrule "special interest groups who push radical agendas"—by which they mean BlackRock BLK, Vanguard, and State Street STT.

Active Managers Concur

Index providers' final adversary is their oldest and fiercest detractor: active portfolio managers. Naturally, they disliked their investment rivals from the very start, with one particularly virulent manager calling index funds "un-American"—a quip that delighted Jack Bogle for the rest of his life. (Not to be outdone, a Wall Street firm later published a white paper called "The Silent Road to Serfdom: Why Passive Investing Is Worse than Marxism." Never say that investment professionals lack a sense of humor.)

Active portfolio managers' arguments are whatever they hope will be heeded. Every index fund is below average, because it matches a costless benchmark's returns, while subtracting expenses. Index funds distort the capital markets, by inflating the prices of the stocks that they own, while neglecting other securities. Index funds reduce the efficiency of the financial markets by blindly purchasing whatever is in front of them. (Eventually, this final charge might stick, but it is incorrect today, when trillions of dollars remain in active investors' hands.)

The True Issue

Clearly, active managers act in bad faith. They argue for their own benefit, rather than for their listeners'. In contrast, indexing's political opponents are more sincere. The left wholeheartedly believes that unfettered corporate executives are reckless, and the right that investing by ESG precepts is pernicious. But the politicians also have hidden motives. Underlying the left's criticism is the belief that businesses can become too big, but governments cannot. For its part, the right was fine with portfolio managers voting their funds' shares, until those shares were voted in a way that it disliked. Its "principles" are in fact preferences.

Ultimately, indexing's detractors identified the wrong enemy. The danger to the country’s economy and equity marketplace, to the extent that it exists, does not come from indexing per se. Rather, it arises from the existence of giant money-management firms, regardless of how they invest. Whether active or passive, they inevitably own most stocks in the marketplace (the left's complaint), while facing pressure from vocal shareholders to follow ESG principles (the right's concern).

With the debate on indexing, the public's instincts are correct. Index funds are excellent investments, no more and no less. Power to the people.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/09-25-2023/t_f3a19a3382db4855b642d8e3207aba10_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)