What Can Private-Market Investors Learn From Hedge Funds’ Heyday?

Regulation, disclosures, and compliance mark the path to the mainstream.

Editor's note: This article first appeared in the Q2 2022 issue of Morningstar magazine. Click here to subscribe.

Public-market valuations and downbeat macroeconomic forecasts have led investors to cast an envious eye to private-market investments, which can seem to provide a solution for market volatility, regulatory reporting, and continuous disclosure requirements. While pension funds and longer-term liability matchers have long incorporated these assets into their portfolios, more recently a broader range of institutional investors, and even high-net-worth individual investors, have been making the crossover.

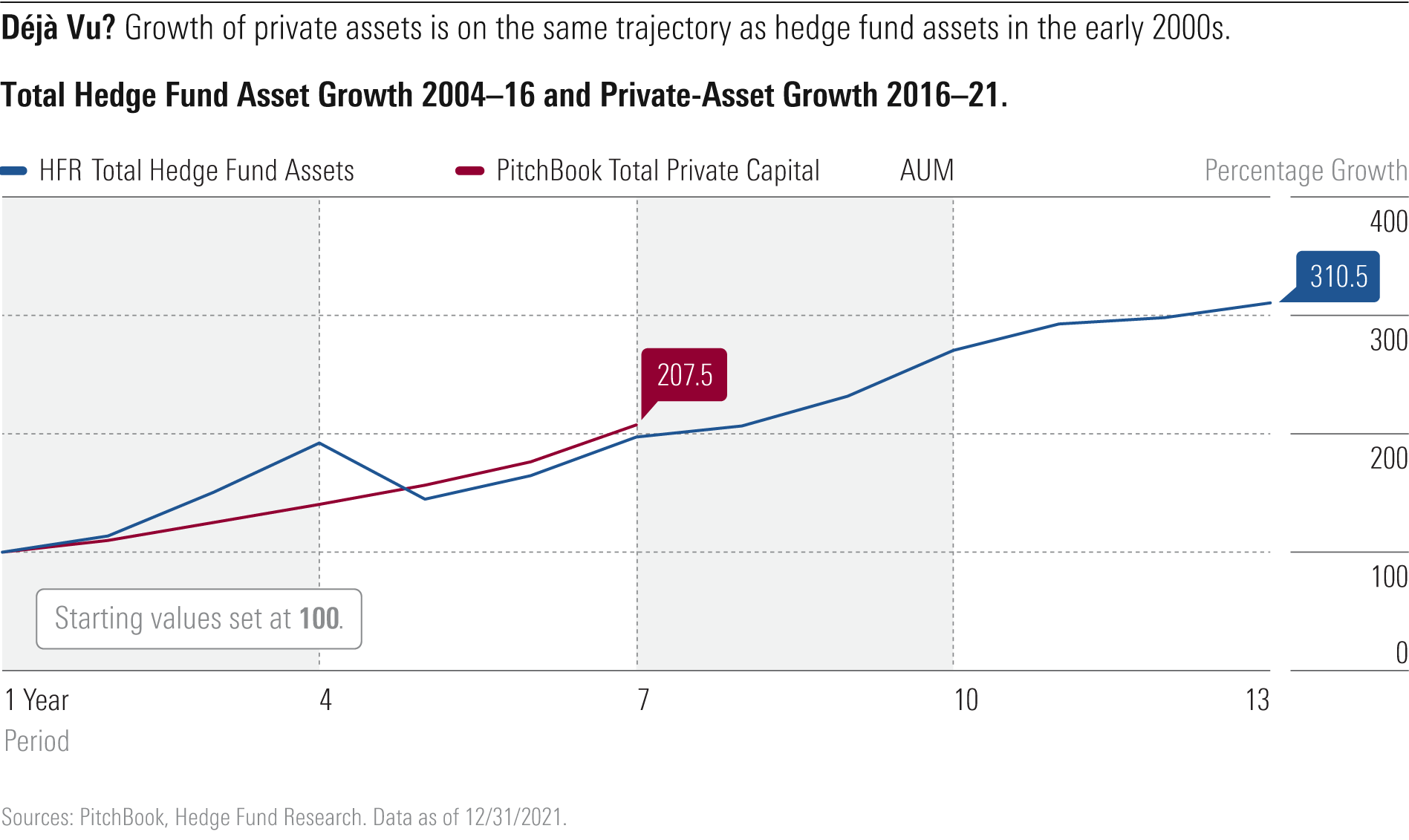

There are clear parallels between what is happening today and the institutional cleansing that hedge funds experienced in the early 2000s, before the masses were let into the party. Mark Twain is often quoted as saying, “History never repeats itself, but it does rhyme.” As private and public markets converge and become more widely available, what can investors learn from the democratization of hedge funds into liquid alternatives 20 years ago?

Why Is This Convergence Occurring?

The last quarter of the 20th century saw a reduction in corporate reliance on banks for their funding needs. First, the awakening of the sleepy bond markets in the 1980s fueled the large debt-backed takeovers of the era. Then, the growth of shareholder culture, long before environmental, social, and governance became a thing, had a major influence on how companies financed and operated themselves in the equity-backed expansion of the 1990s. In 1999, the United States deregulated financial markets with the repeal of the long-standing Glass-Steagall Act, and new global financial titans were created. Also that year, the euro was introduced. These events combined to create new funding sources for companies. The turn of the millennium brought in the advent of financial globalization and, with it, growth in capital market issuers, currencies, and complexity.

These changes fundamentally changed the capital-formation process for companies in the 21st century. Although the time from founding to IPO has been consistent over the years, the growth rate of firms during their private phase now snares the bulk of value creation. According to Goldman Sachs, the median company now goes through three equity financing rounds before the IPO, whereas it was just one in 2011. This also suggests that companies are raising twice as much capital before IPOs as they were a decade ago. Morgan Stanley notes that companies have raised more money in private markets than in public markets in each year since 2009.

So, it’s not surprising that firms trading public-market securities want a slice of the action. Besides value creation, early exposure to companies provides public-market firms with other advantages. It can help firms secure the limited, and potentially lucrative, future IPO allocations. Private markets tend to offer more transparent disclosure without the oversight of the stringent public insider-trading laws. There is also the informational advantage; early ownership gives firms insights into their listed portfolio holdings. A sweetener comes in the form of different asset-valuation mechanisms, which may deliver a volatility-damping effect that smooths portfolio returns.

These benefits aren’t new. Hedge funds have participated in private deals since the early 2000s. The approach in 2022 differs in how they manage the liquidity mismatch. Before 2008, liquid and illiquid assets were blended into the one portfolio. Today, hedge funds are much more likely to use a segregated “side-pocket” arrangement for private assets, allowing investors to choose the extent of the exposure instead of the manager. Alternatively, many hedge funds even provide a stand-alone fully drawn-down private equity fund or a coinvestment opportunity for specific deals.

A key differentiator of public-market funds is the capital-duration advantage. Having evergreen capital, or to not have to go back to investors to raise new funds, means they can be life-cycle investors, participating from early pre-IPO financing rounds to late maturity across multiple business cycles. Being more hands-off and not seeking board seats can be enticing for company management. To fend off the competition, top-tier private equity managers have been seeking permanent capital pools. Most of these management companies are now themselves publicly listed; the switch from lumpy performance fees to the more stable income from management fees on this permanent capital is attractive for both shareholders and general partners, who are increasingly paid with stock options.

Investor expectations have also changed. As decentralized platforms and pricing techniques enter the mainstream, innovative liquidity mechanisms may, in turn, attract a new class of investor—a generation attuned to receiving instant asset valuations and liquidity on nonfinancial holdings. This democratization offers a huge opportunity for firms to diversify their investor base, a trait we’ve seen with special-purpose acquisition companies.

Much of these changes have been evolutionary rather than revolutionary, but we can’t shake a feeling that we’ve seen this all before in the most recent sector to become mainstream: liquid alternatives.

Hedge Funds Grow Up

Hedge funds, a sector still dominated by equity long-short offerings, demonstrated their worth during the technology wreck of the early 2000s. They delivered positive returns, while equities declined by 44%. The collapse of Long-Term Capital Management in 1998, an event that first brought hedge funds to public attention, was long forgotten. Still the purview of high-net-worth individuals, hedge funds attracted institutional investors for their low volatility and seemingly uncorrelated returns. Assets grew substantially between 2002 and 2008.

To cater to the new institutional client base, the hedge fund industry had to adjust its periodic reporting and disclosure to high-net-worth investors to the more regimented requirements of trustees, boards, and other institutional investors. Operational due-diligence experts became ubiquitous, helping align fund operations to these new requirements. This process of so-called institutionalization, which was a comprehensive overhaul to meet compliance and due-diligence standards, was the start of making alternatives mainstream.

The flood into private assets—Morgan Stanley estimates that the inflows into private assets over the past 45 years have risen by over 470 times—is requiring a similar transformation. General partners still focus on finding deals, but limited partners (the investors) now require much stronger fund governance and oversight. The growth in the number of private firms (between 7,000 and 30,000, depending on the data provider) empowers investors, who no longer face a “take it or leave it” approach to gain access to the sector.

The focus of these institutional investors on transparency, independence, and conflicts of interest has driven innovation and transparency in private markets. New platforms facilitate communication between investors and private firms, and investor advisory committees drive engagement and transparency in decision-making. The independence of advisors and administration still lags hedge funds but is trending in the right direction.

Regulations, Transparency, and Disclosure

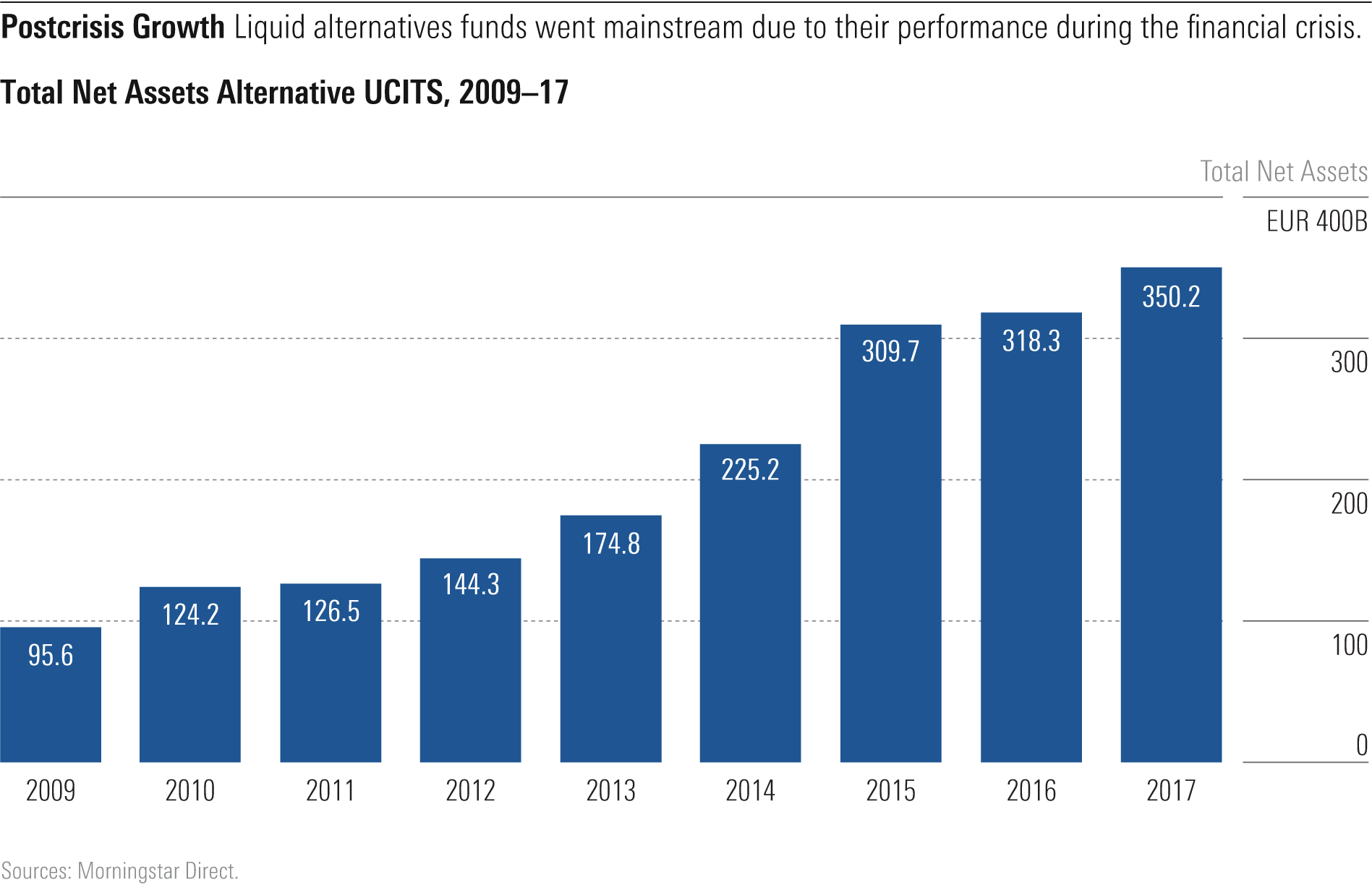

Capital-market harmonization was a key pillar in the convergence of the European Economic and Monetary Union. The onerous UCITS regime, introduced in 1985, was modified by UCITS III in 2003 as tighter risk-management considerations allowed for an expansion in permissible investments. Short-selling was not permitted, but now derivatives providing the same return profile were, all within products providing a minimum of twice-monthly liquidity. This simplified investment framework, a perception of safety, and reduced administrative burden led to soaring popularity of hedge-fund-like investments.

In the U.S., liquid alternatives fell under the Investment Company Act of 1940—an access point for those who did not meet the high minimum investment requirement and qualified investor tests. It also removed the need for subscription documents, making allocations simpler than directly investing in hedge funds or private equity funds. Both European and U.S. regulations required at least 85% of a public portfolio’s exposure to be to liquid assets.

The loose monetary policy of the early 2000s enabled the performance of the HFRX Global Hedge Fund Index to keep pace with the S&P 500 between 2002 and 2007. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, the complex Cayman Island structures underpinning hedge funds came under scrutiny. The layers of fees, hidden leverage, and side-pocketed assets unmasked many allocators, blinded by the good times to the hidden risks. Subsequently, the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act aimed to regulate the financial sector, but on a relative basis, those investors with a hedge fund allocation outperformed those without. This performance kept investors interested in hedge funds (see exhibit below), but the balance of power had shifted. Institutions, using the sector’s postcrisis decline in assets, demanded the same uncorrelated returns as before but in a liquid, transparent form with a much lower fee.

The torch of Dodd-Frank also delivered more disclosure on the operations of private-market firms. In 2014, the SEC uncovered unfair practices and violations of fiduciary duties previously hidden from investors. Today, with an SEC estimate of $18 trillion sitting in private funds, Dodd-Frank has not been able to deliver full and fair disclosure of private funds, forcing regulators to act on both systemic risk and public-policy grounds. In February, the SEC proposed new rules on disclosure of fees, audits of returns, fee-charging practices, and conflicts of interest for private funds. The agency usually takes a disclosure approach to regulation, but the persistence of many private-market practices forced stronger rules. It flagged providing preferential treatment to certain investors, the charging of certain fees and expenses, the lack of governance mechanisms, and putting the firm’s own interest ahead of the client among many in its 342-page document. It’s a well-trod line, but the agency’s justification is that increased transparency, disclosure, and competition will help both investors and those raising capital. While the measures contain a populist angle, a consistent regulatory framework is necessary before the sector can scale. Yet the elephant in the room remains unaddressed—that of how private equity returns are calculated.

On disclosure, private equity has a multitude of fees beyond the management and performance fees most investors are familiar with. Fees for advice and facilitation on each portfolio company are common—whether that be operational, financial, or portfolio monitoring. The SEC described these as fees charged for services that “the investment advisor does not, or does not reasonably expect to, provide to the portfolio investment.” As was the case with hedge funds, excessive pass-through expenses such as travel to source investments, high-end technology, deferred compensation for new hires, and office overheads are an area of focus. These costs can be an extra 5% to 8% to investors and are often switched to pass-through fees to show a decline in headline management fees.

Technology and the Ability to Scale

Before 2008, funds of hedge funds were the most common entry point for investors seeking alternative investments. Investors didn’t have large due-diligence departments or the data resources to value complex derivatives or to identify and gain access to capacity-constrained managers. The multilayered fees and redemption halts during 2008 left a bad taste in investors’ mouths. Although diversified across upward of 25 managers, if an individual fund had one bad liquidity event, the whole fund of funds could collapse.

In the 2010s, the institutional requirements of retaining control of the assets shifted demand to other vehicles, such as managed accounts. These scalable platforms, which could easily house hundreds of managers and funds with real-time risk exposures and valuation validation, soon became the preferred mechanism. The next iteration was the entry of aggregators that, at a cost, combined small-accredited investors to meet a fund’s minimum investment amounts.

In private markets, smaller noninstitutional platforms have strong growth, providing liquidity pockets, Dutch auctions, and request for quotations to these investors. The larger private funds have no incentives to engage with these platforms, but much as managed accounts took liquid alternatives to the mass market, private funds need to find a way to collaborate to achieve broader acceptance.

Fund Access Points

Traditional asset managers were aware of the growth of managed accounts. They brought institutional-grade infrastructure and deep distribution networks, capabilities that could touch not only U.S. and European markets but also allow for feeder funds from Asia and Oceania, bringing unprecedented scale—a requirement given the absence of performance fees. A flagship offering could mutate overnight into a long-short or market-neutral version. These firms could provide in-house aggregated risk reporting; third-party support services such as prime brokers, custodians, and administrators could easily handle the breadth. While no one measure drove the assets under management growth in liquid alternatives during the 2010s, the convergence of traditional funds and hedge funds lit a fire under the category.

In private markets, the closed-end fund structure has been the typical publicly traded entry point, but innovations found in other markets are now entering the U.S. One example is interval funds, which provide investors access to private credit and debt, with close to $40 billion in issuance across 70 products. These structures come with caveats, mainly about how they price assets and deliver the proceeds.

The notice period is well in advance of the liquidity window, and the setting of the redemption price is significantly after the redemption request is made, leaving a cloud over the proceeds investors receive. As we saw with funds of hedge funds, once redemptions are scaled back, investors submit bigger requests in subsequent windows, and illiquidity quickly results, leaving investors locked in a product with a declining net asset value. Public- and private-market convergence, therefore, is most likely to occur first in crossover funds, where a slice of private exposure is added to a public-market portfolio or within target-date funds, whose investment horizon is more aligned with private-market assets.

Did Liquid Alts Meet Expectations?

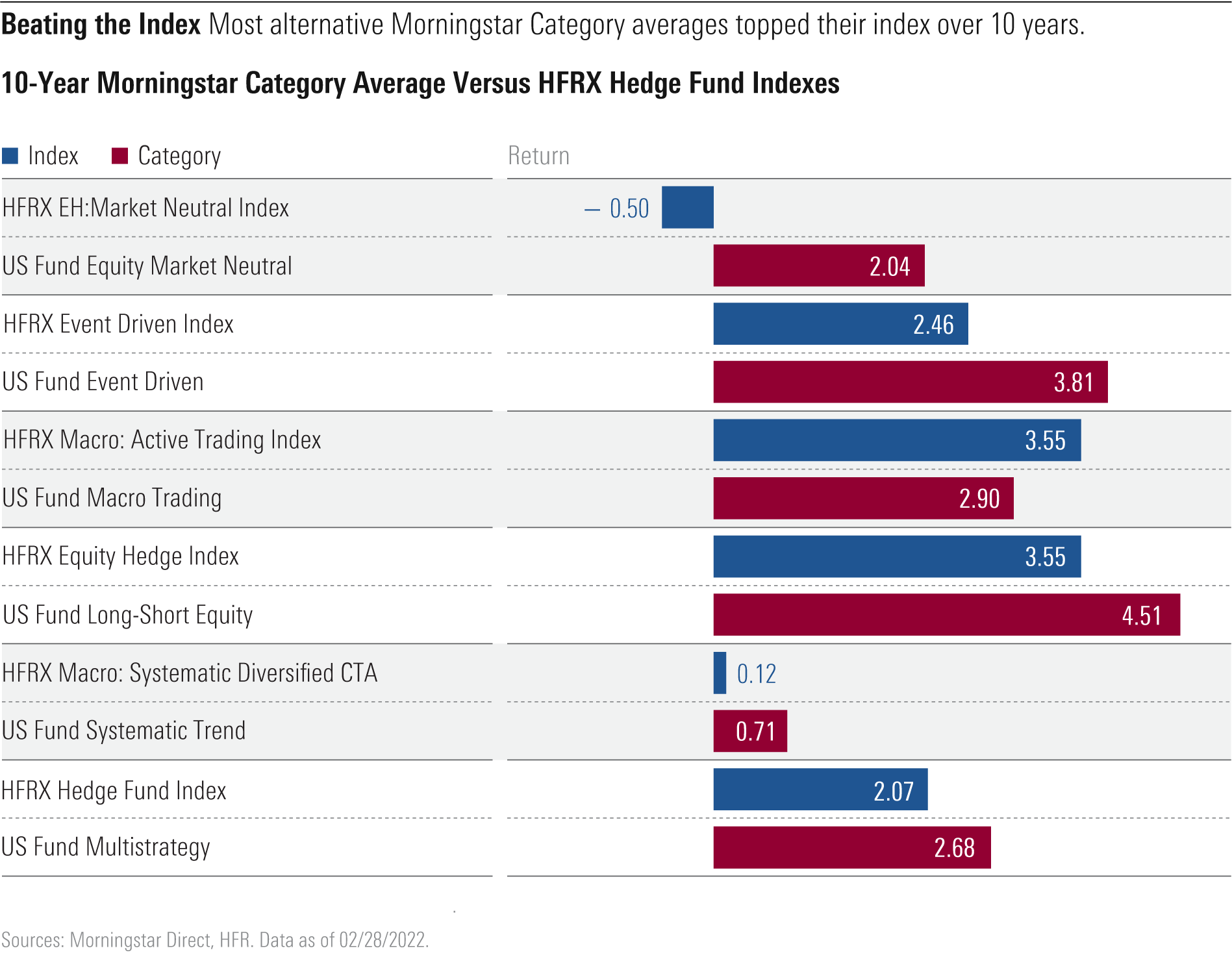

The most frequent criticisms of offering illiquid products in liquid form are that investors lose the illiquidity premium, manager quality is poor, and the strategies are constrained. Investors may have harbored unrealistic expectations of receiving the returns of top-tier hedge funds in a daily priced form, yet the Morningstar Category averages over the past decade to February 2022 in many cases exceed HFRX hedge fund indexes. These are very small datasets often dominated by either public equities or liquid futures, areas where we wouldn’t expect a liquidity premium, but it still raises the question of whether the vaunted illiquidity premium is overstated.

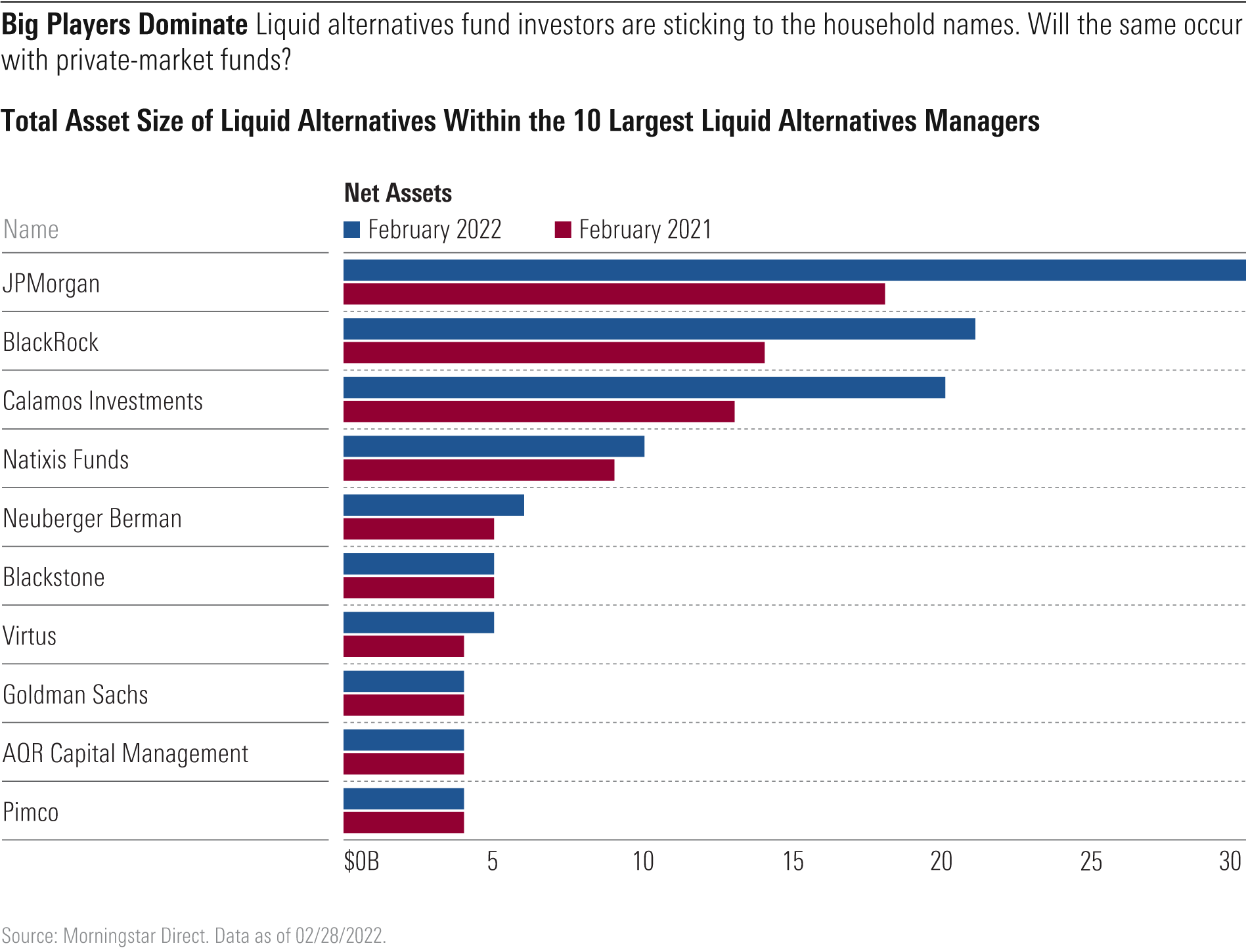

The quality of these offerings is a valid concern, but the subadvisors in these categories contain names such as AQR Capital Management, Graham Capital Management, Man AHL, and Blackstone BX, which has access to heavyweights D.E. Shaw and Two Sigma in its multimanager portfolio. Many investors stick to the household names; the vast global distribution networks of JPMorgan Chase JPM and BlackRock BLK control nearly one third of liquid-alternative AUM.

Morningstar research has noted a first-mover advantage in the most popular liquid-alts products. Longevity, familiarity, and a strong Parent Pillar appear to be prerequisites for success in a category with a short shelf life and high lineup churn. This suggests that the first movers to cross over from private markets may well take, and retain, the lion’s share of assets.

In terms of execution, liquid alternatives may use leverage, just not as much as hedge funds, but there are very limited strategies where this would be a disadvantage. Breadth of securities traded, or gaining access to markets such as commodities, may be more of a limitation, but as the first exhibit showed, we see minimal evidence of this.

Applying the Parallels

Private markets are on the radar for many investors, but the parallels to the formation of liquid-alternatives markets shouldn’t be ignored. We are toward the tail end of the institutionalization of the private markets. A much broader range of institutions is now investing, alongside the traditional asset base. Almost every global asset-management firm now has a private-markets division, and growth in product availability is inevitable.

As Wall Street has taken notice, so, too, have global regulators, seeking to provide investor protections and apply public-policy settings. Debate rages as to whether private equity returns have fallen or whether they confer any positive returns over a stock index fund. This will continue until there is uniformity in valuation and adequate disclosure by private-market firms. Many investors, including professional ones, will continue paying vast fees for little in the way of differentiation.

Financial and technological innovation is bringing solutions, but there is no incentive for the big players to provide clarity on data or operations. This was the same with hedge funds until managed accounts transformed how allocators could interact with fund managers. Unfortunately, it took the extremes of a financial crisis to shift that balance of power in favor of investors. Baby steps have been taken in specific markets such as credit and property, but with high-profile ARK Invest leading the crossover with a public/private equity product, in the form of an interval fund, it could prove a catalyst for copycats to follow.

Ultimately in private equity, as with all investments, successful investors need to be able to identify the winners—whether it’s using sector insights to win auctions and drive value, being able to execute a repeatable process, or targeting specific characteristics in firms where investors know they can add value. The idea of diversifying into companies and segments not represented in major public-market indexes is compelling, but what premium over public markets should be expected for tying up capital given the associated opportunity costs, fees, lack of disclosure, leverage, and complexity risk?

Until this can be qualified, it may be easier to seek private-market benefits in the public markets by, for example, selecting small-cap securities with low EBITDA multiples and modest leverage, or even investing in a listed private equity firm itself.

Simon Scott is director, alternatives ratings, at Morningstar Research Services LLC.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/FNDLNORUIBFD5KKEXASUD67L6Q.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BHGJBKNFZRB7NHXO3ZLRNAHOIY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/RENAPI2NVVDIDCNNAGV6XAUCM4.jpg)