What Are Carbon Markets, and Should You Invest in Them?

The appeal of investing in carbon markets has to be weighed against their risks.

With the costs of climate change becoming more visible, governments and corporations alike have set out ambitious agendas to cut their carbon emissions to zero. Reducing corporate travel, turning to renewable electricity, and moving to more-efficient buildings are all practical steps companies can take to reduce emissions. But given the scale of fossil fuel emissions, this often isn't enough.

Enter carbon markets, which exist in two formats. Compliance carbon markets are regulated by governments; a CCM is a marketplace in which permits to emit carbon are bought and sold. Regulated entities in these markets—like utilities and gas companies—are mandated to turn in permits for every ton of carbon they emit. Meanwhile, voluntary carbon markets are the markets in which carbon offsets—portions of projects that decrease the amount of carbon in the system—are being bought and sold.

Though corporations are the largest players in these markets, financial market participants have begun to turn to the markets in search of financial profit. In North America alone, since 2020 six exchange-traded funds have launched that offer exposure to carbon contracts, and the number of investment companies/hedge funds registered in California’s Carbon Program has more than doubled since 2019. Though still niche, their growth in recent years warrants further exploration around their merits as an investment, and the implications for an environmentally focused investor.

What are the types of carbon markets?

Carbon markets exist in two forms, but the goal is the same: to put a price on carbon emissions. Still, there are important differences to consider between the two.

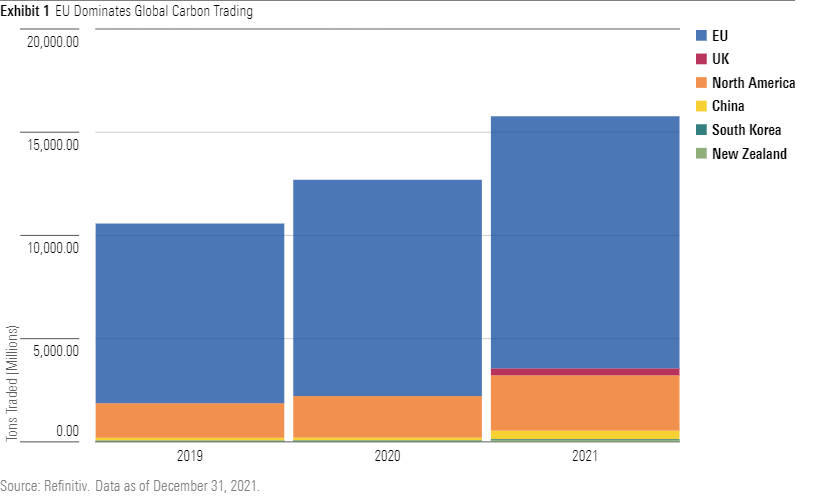

Compliance carbon markets are overseen by governments both at the individual sovereign level and by broader organizations like the European Union. In areas where governments have established CCMs, certain companies—like utility providers or cement producers—must have permits for each ton of carbon dioxide that they emit. These programs are often referred to as cap-and-trade systems; governments cap the amount of carbon that the companies in the program can release and allow the participants to trade the permits amongst themselves. Though the rules and enforcement mechanisms differ by market, the product being traded—the right to emit carbon—is the same. There are a number of these programs in place, with the EU emissions trading system by far the biggest, owing to its longevity (it’s been around since 2005) and the emphasis that lawmakers place on developing these markets.

Voluntary carbon markets aren't regulated by governments, and the contracts being traded are carbon offsets. Carbon offset contracts represent sponsorship of a project that is meant to decrease the amount of carbon being emitted, which serves to offset a company's own emissions. The projects backing these contracts are varied; they can represent a protected forest, a solar farm, or clean cooking stoves. Though efforts to verify and standardize these offsets have come a long way in recent years, there are still concerns surrounding their legitimacy, which has hampered adoption.

Still, each has grown significantly in recent years. According to data from Refinitiv, approximately $850 billion of carbon emissions contracts were traded in global compliance markets in 2021, up 164% from the year prior. Data on VCMs is harder to pin down, as many of the contracts change hands on over the counter markets. CBL (the largest exchange for offsets) saw turnover of $400 million in 2021.

How do financial market participants use the contracts?

Data on financial market participation in these markets is limited. Derivatives positions within funds are difficult to track, which makes searching for the holdings a challenge. However, there are signs that financial actors are increasingly turning to carbon markets as an investment opportunity.

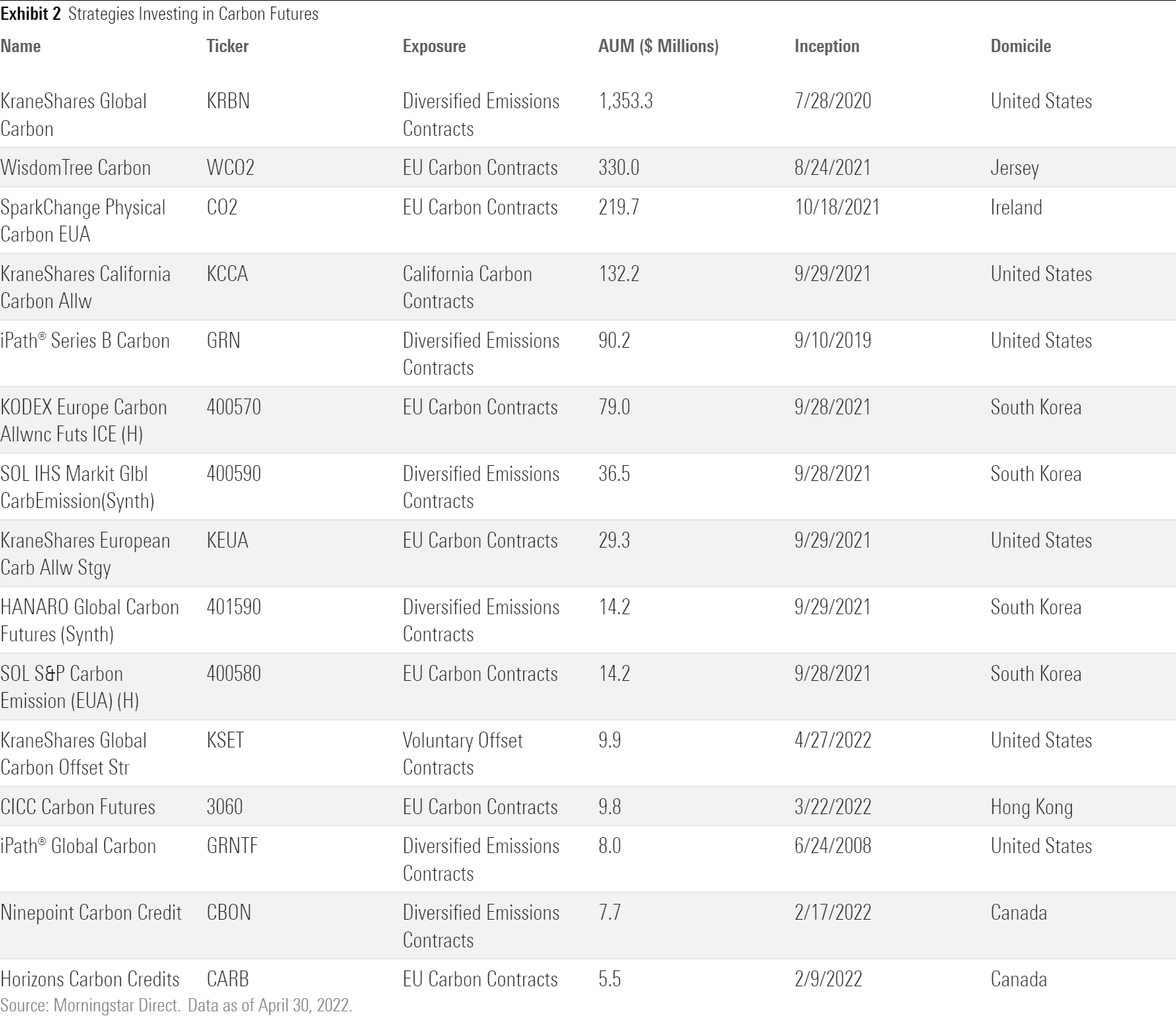

First, a handful of standalone investment options have launched that invest exclusively in these markets. Investors in these strategies expect the cost of carbon to rise over time, as governments winnow the number of contracts available in an effort to curb emissions. They’re similar to single-commodity ETFs like the U.S. Oil ETF USO that invests exclusively in contracts of one commodity. We’ve identified 14 strategies with approximately $2.3 billion in assets under management that invest exclusively in futures contracts tied to carbon markets.

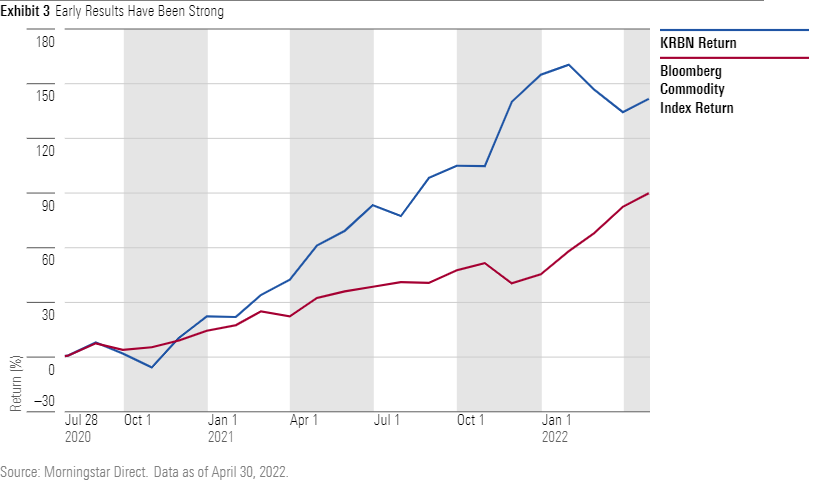

The KraneShares Global Carbon KRBN—which invests in three emissions contracts—is by far the largest, attracting more than $1 billion since its July 2020 launch. Though the market is still small, its growth rate is impressive, and strategy launches have occurred quickly. Just three of the strategies were launched before 2021, with eight launched in 2021 and four already launched in 2022.

Besides the rise of strategies that offer this direct exposure, evidence of other market participants has cropped up, too. By looking at the entities that have registered for California's Carbon program, we were able to identify more than 40 investment companies/hedge funds that participated in the program as of March 2022, up significantly from just 16 in 2019. This doesn't include proprietary or other trading firms that are also active participants in these markets. Investors here ply a number of different strategies; there are trend-followers who see another diversifying contract to allocate to, commodity managers who evaluate the supply and demand thesis and allocate from a fundamental view, and arbitragers who seek to exploit differences between the futures and spot price, among a broad range of others who are looking for the price in these contracts to appreciate.

Lastly, Morningstar has talked with mutual fund managers who are beginning to incorporate these contracts into their strategies. Pimco’s commodity team has carved out an allocation to carbon markets in its two Silver-rated commodity strategies, where the team trades California emissions contracts through a fundamental lens. Systematic trend managers have begun allocating to these markets, too, with the Neutral-rated UCITS manager Winton allocating to them in its Winton Diversified Fund.

What are the risks?

Relative to more-staid parts of the investing landscape, carbon markets are a newcomer. Permits on the EU ETS only began trading in 2005, and investors didn’t begin to look at the space seriously until the past few years. With more attention from regulators and investors alike, they will continue to evolve, which makes investing a tricky proposition.

In compliance markets, the most significant risk to investors is political risk. These markets are human creations, incepted by governments and overseen by political actors. The intent of the markets is to assign a realistic price to carbon that forces companies to consider the externalities of emissions and determine whether the emission is worth it. If the price of carbon becomes too volatile, or if a government feels that the objectives aren’t being met, it can propose changes to the market that affect the price of the contracts.

Besides the unique political risks that come from these markets, more-traditional factors will drive their day-to-day price movements. Increasing economic activity should drive more demand for carbon emissions, raising the price, and the opposite would occur during a recession.

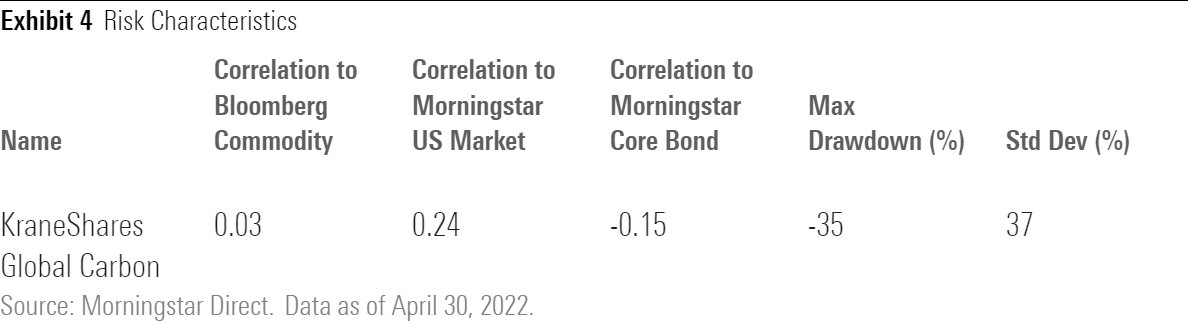

Investors should also be mindful of the impact that increasing financial market participation will bring to the space. We’ve written about how the increasing institutionalization of commodity markets led to higher correlations to broad asset markets, and the same pattern could play out for these markets. Thus far, KRBN—the most-established strategy—has been fairly uncorrelated to other assets. Still, this is over a very short time period, and it’s unknown if this pattern will hold as more money flows into the space.

Returns have also been solid, though its risks have been on display. It experienced a drawdown of more than 35% in just 29 trading days, and its volatility is significantly higher than equity, fixed-income, and even commodity markets.

Is it ESG?

Without a doubt, carbon markets have a role to play in transitioning to a net-zero world. By placing a price tag on carbon emissions, CCMs incentivize companies to look to other options. And by funding projects that reduce the amount of carbon being emitted, companies can offset their emissions that they can’t fully eliminate.

However, buying these contracts with the intent to sell them along to an emitter—as investors in these markets are doing—does not provide any direct environmental benefits. There is a slim case to be made that financial market participants provide liquidity and legitimacy to these markets, but ultimately simply buying and then selling a carbon contract results in nothing more than a monetary gain/loss.

Investments in carbon markets are poised to grow in the coming years, and with that, changes to their return profile will continue. Investors adding an allocation to carbon in their portfolio should keep that in mind, and understand that the risk/return profile of these contracts could change significantly in the years to come. Though allocations to carbon in specialist commodity or trend-following strategies may indeed provide some diversification benefits for those managers, the case for a standalone allocation in an individual’s portfolio is slim.

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/XTXQYAMAL5EKRLGIS3IDVAZ3R4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/3J75DKCBIZCTJMRFWSSJSHHCJ4.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/DJVWK4TWZBCJZJOMX425TEY2KQ.png)