Have Growth Stocks Bottomed?

They are off to their worst start since the Great Depression.

Making History

It’s been a terrible year for growth stocks.

In late January, I published “The Stock Market’s Dominoes Are Falling,” which showed how equities were following the stereotypical bear-market pattern, by imploding from the outside. First to falter had been the most-speculative issues: meme stocks, special-purpose acquisition companies, and ARK Innovation ETF ARKK. Then came the rest of the small-growth universe. Finally, in January, the industry leaders cracked. At the time of that article, all growth stocks were in free-fall.

After staying afloat for several weeks, they resumed their slide in April, which featured Nasdaq’s largest monthly drop since 2008. The overall news was worse yet. Through April, U.S. growth stocks had posted their weakest performance since 1932. Not since the Great Depression had they fallen so far during a year’s first four months—not in the 2008 global financial crisis, nor the 2000-02 technology selloff, nor the 1973-74 bear market.

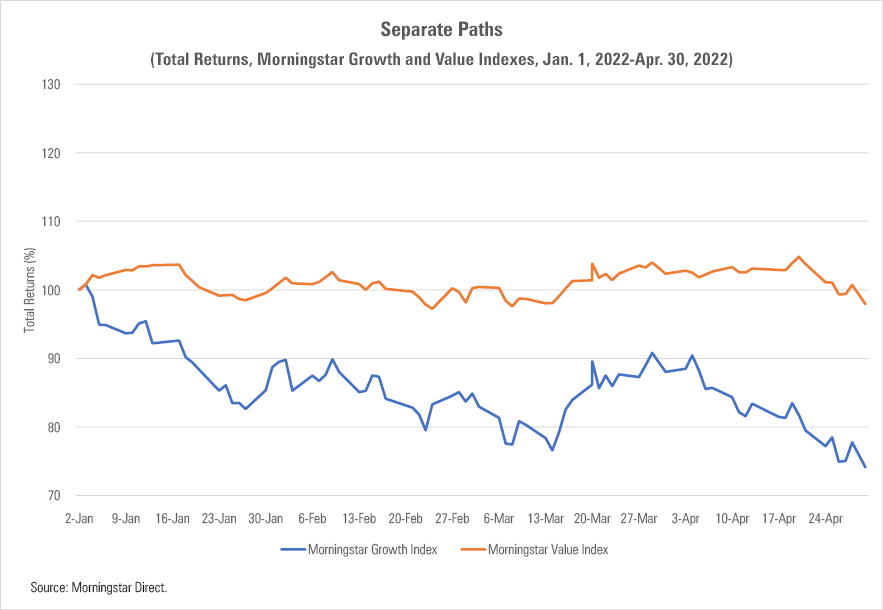

The grim details appear below. As the chart indicates, value stocks are unfazed. the Morningstar US Value Index is down only slightly for the year to date. Life has been perfectly acceptable for most U.S. equities. Not, however, for growth companies, as the Morningstar US Growth Index has slumped by 25.9%.

It Could Be Worse

Which leads to the headline's query: Has the growth-stock slump run its course? Naturally, growth-stock investors believe so. Earlier this year, ARK Innovation portfolio manager Cathie Wood averred that after absorbing its pounding, her fund should be considered a "deep value" investment. Since that comment, ARKK has dropped another 45%. Make that a very deep value investment.

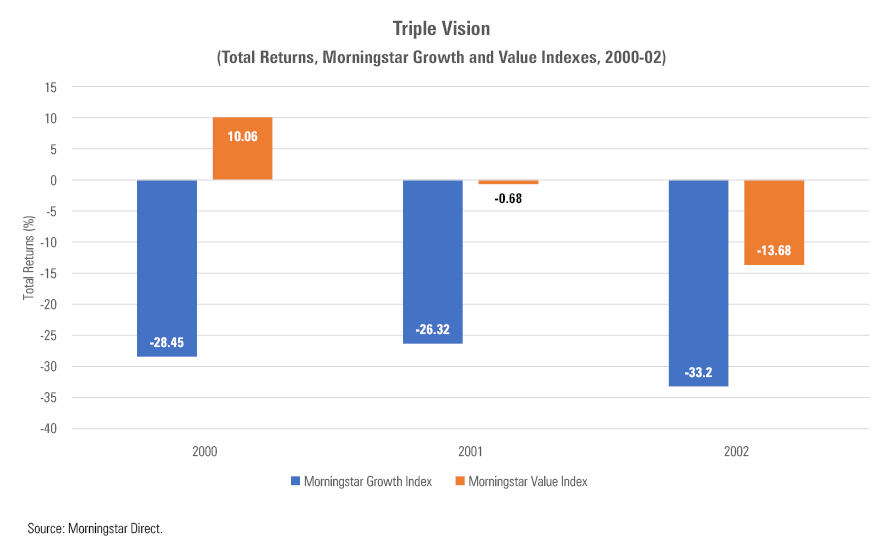

Unfortunately for growth-stock devotees, the math doesn’t necessarily work that way. Consider, for example, how the Morningstar US Growth Index fared entering the millennium. In 2000, that index lost 28%, while value stocks gained 10%. The performance discrepancy was even greater than today (although occurring over 12 months rather than four). However, that outcome did not presage a growth-stock rebound. Far from it.

As Wood can attest, what has descended can always descend further. If growth stocks are to recover, they require one of two circumstances: Either the economy must change, or they must become too cheap for investors to ignore.

Economic Matters

It's not that the economic reports are entirely bad. Inflation is rampant because of soaring commodity prices and supply chain disruptions. (Also to blame may be fiscal and monetary policies, although the jury must remain out on those effects, as they take longer to assess.) Consequently, the Federal Reserve is raising interest rates, always a challenge for equity prices. On the other hand, employment is booming and researchers expect aggregate corporate profits to grow by 5%-10% during the first quarter, despite higher input costs.

However, current conditions are inhospitable for growth stocks. As their stellar 2020 returns demonstrated, growth stocks perform best when a recession lurks and interest rates are low, for two reasons. First, as their businesses tend to be healthier than those of value stocks, growth companies are better positioned to weather economic downturns. Second, because growth stocks are primarily prized for their future output, they suffer more when interest rates rise. Higher interest rates reduce the value of prospective earnings.

(The above paragraph smacks of hindsight analysis. It is true, as Morningstar’s Don Phillips has long remarked, that stock markets are devilishly difficult to predict on New Year’s Day yet simple to explain on New Year’s Eve. That said, 2022’s early returns were easier than most to forecast, because the salient features were established entering the year. In Jan. 4’s “The Stock Market Faces Strong Headwinds in 2022,” Morningstar’s Dave Sekera correctly identified the looming troubles, while citing value stocks—in particular, energy firms—as a refuge.)

Although some observers expect that the Fed's interest-rate hikes will halt the economy, most are sanguine. In a recent poll of economists by The Wall Street Journal, 72% believed that the United States would remain recession-free during the next 12 months. Should they become more pessimistic, the relative fortunes of growth stocks will likely improve. For them, weak economic news often means strong investment results.

Is the Price Right?

Alternatively, growth stocks may have become so cheap that they no longer require a friendly economy to revive. But judging that event is even trickier than foretelling the economy. Determining the “correct” price for growth stocks requires superhuman (and super artificial intelligence) abilities. One needs to know not only the amount of future corporate earnings, over many years, but also their volatility, as well as the level of interest rates. Good luck with all that.

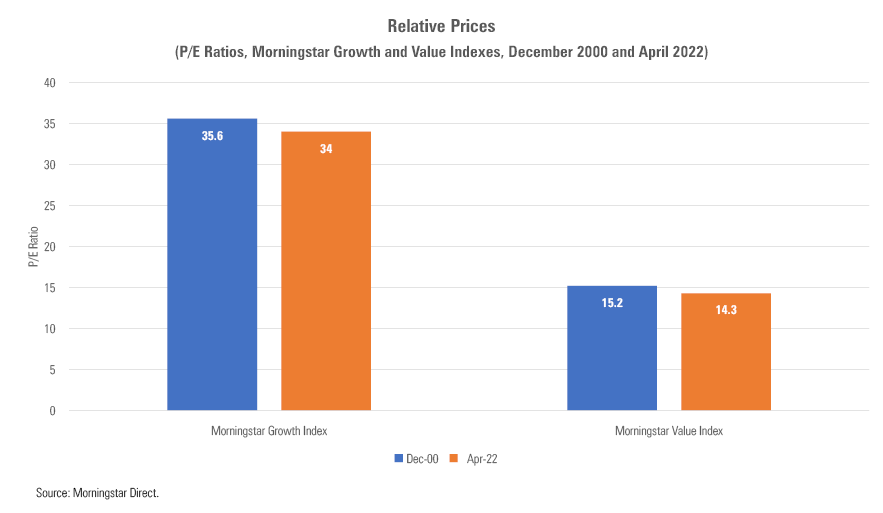

However, if no calculations can assist, we can at least test the proposition via the back of a metaphoric envelope. In December 2000, growth stocks were in a rut, much as they now are. Yet they continued to struggle for another two years. Was that because their prices were well above current levels? If so, one might reasonably see a light at the end of the growth-stock tunnel. If not, however, it would be difficult to argue that cost alone will spark a growth-stock rebound.

This test is both easy to administer and easy to interpret. Each month, Morningstar computes the price/earnings ratios for the growth and value indexes. The following chart compares the December 2000 P/E ratios for each index with those from April 2022. (Technically, I updated the most-recent available figures, which were from March, but close enough.)

Oh dear. When comparing the P/E of growth and value stocks, today’s totals almost exactly match those from December 2000, a time that represented not the bottom for growth stocks, but instead the midpoint. (When I examined the indexes' price/book ratios, the outcome was the same.)

Wrapping Up

None of this is to state that growth stocks won’t rally. If this article marked the week that growth stocks recovered, I would be amused, but not surprised. That said, nothing suggests to me why their turnaround will occur anytime soon. The end of interest-rate increases is nowhere near in sight; recession does not appear to be imminent; and nothing about growth stocks’ prices suggests that they are a bargain. I conclude this article less optimistic about growth stocks’ prospects than when I began it.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MFL6LHZXFVFYFOAVQBMECBG6RM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EGA35LGTJFBVTDK3OCMQCHW7XQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)