Did Fund Managers Misjudge the Risks of Russia's Most Popular Stock?

Emerging-markets funds must deal with a limited universe--but you don't.

Editor's note: Read the latest on how Russia's invasion of Ukraine is affecting the global economy and what it means for investors.

Against the tragic scenes from Russia's invasion of Ukraine, financial issues take a back seat. It's understandable, though, if investors whose funds took a hit from the sharp decline in Russian stocks would want some explanation.

With hindsight, it might seem to have been unwise for portfolio managers to have invested in Russia. After all, that country posed substantial investment risks even before the Ukraine crisis gained attention in recent months.

However, for Sberbank, the Russian stock that was most popular with emerging-markets funds, the portfolio managers with whom we have spoken over the years did not act recklessly. They outlined solid reasons to own it and recognized many of the special risks it faced based on its location. They offered reasonable explanations of why they had decided to discount those risks in this case. As it turned out, they were right--about those risks. What tripped them up was an even more serious hazard that--unlike those risks--had little or no recent precedent.

In other words, the managers either considered it highly unlikely that Russia would launch a full-scale invasion of a neighboring country and crippling sanctions would be imposed as a result, or they failed to envision such scenarios. They were left holding shares in a seemingly rock-solid company whose value evaporated virtually overnight.

This episode demonstrates that the task of evaluating and responding to perceived risks can be even more complex and challenging than most of us might think--especially in emerging markets.

A Dominant Company

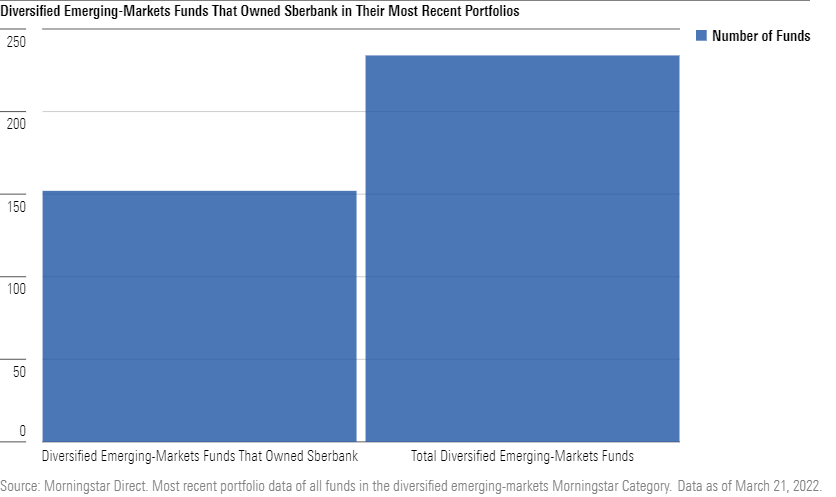

Sberbank was the most widely held Russian stock among emerging-markets funds as of their latest portfolios, nearly all of which were disclosed before the invasion. Fully 65% of the 234 distinct actively managed funds in the diversified emerging-markets Morningstar Category held Sberbank stock either in the local market or as an ADR, according to Morningstar Direct data.

In discussions with Morningstar manager research analysts over previous years, emerging-markets managers have cited Sberbank's dominant position in the local retail banking market, with a market share of more than 40% by some estimates. Prior to the invasion, it regularly posted solid earnings, was highly profitable, and paid a healthy dividend. And it was selling for price/earnings and price/book ratios far lower than what European banks with less-appealing traits were fetching.

Of course, there was a reason its valuation was so attractive: its location. When asked how they assessed the additional risks of the bank's Russian domicile, many portfolio managers told us that Sberbank was not as susceptible to the dangers that had bedeviled some other Russian companies. It's noteworthy that to all appearances, the managers' forecast was accurate--those risks did not materialize. The stock's collapse owed to an outlier risk unrelated to the mishaps that had struck other high-profile Russian stocks.

The Well-Known Risks

There were three key Russia-centric risks the managers would either bring up on their own or would discuss in response to our questions.

1) Landing on Putin's Enemies List

First, would Sberbank's management would somehow run afoul of Russian President Vladimir Putin? Sadly, unpleasant fates for business leaders (or journalists, activists, and others) whom Putin deemed to be getting too powerful or outspoken had become depressingly common. In such cases--with oil company Yukos a prominent example--their companies could suffer as well.

The managers considered this outcome unlikely. They said Sberbank’s management didn't have an outsize public profile and kept out of politics. Moreover, they argued that it was in Putin's interest for Russia to have a successful, well-run retail bank that people could rely on for ordinary transactions. More cynically, one manager said that Putin favored Sberbank because it was easier for him to keep an eye on one dominant bank than if he had to keep track of--and perhaps rein in--multiple players jockeying for position.

2) Misguided Management

A second concern for shareholders of Russian companies: management missteps. Many Russian firms, particularly those run by the ultrawealthy business leaders known as oligarchs, have not been managed in a manner most Western investors would consider shareholder-friendly, or even prudent. Unwise acquisitions, vague accounting practices, or other dismaying corporate tactics were far from uncommon.

According to the portfolio managers we spoke with, Sberbank passed this test as well. It had Western-trained managers who, for years, had run the business in a responsible manner without the questionable forays seen elsewhere.

3) An Unreliable Central Bank

A third worry applies to most emerging markets (and some in the most-advanced markets as well). It's especially relevant for a financial stock. Is the country's central bank judiciously managed? An irresponsible central bank can play havoc with a country’s economy and interest rates, making it impossible to forecast a bank's prospects.

Portfolio managers we spoke with over the years were confident they could discount this risk as well. In contrast to some emerging markets--most notably Turkey, whose leader regularly interferes with central-bank policies in a manner widely considered to be harmful--Russia's central-bank chief Elvira Nabiullina commanded much respect from Western economists and investors. A couple of managers said that they considered her a more reliable central-bank chief than those in many European and North American countries.

Putin first appointed her to this position in 2013. Apparently, he continues to hold her in high regard; in mid-March of this year, he proposed that she continue for a third term, a proposal certain to be approved by Russia's legislature.

The Not-Quite-Black Swan

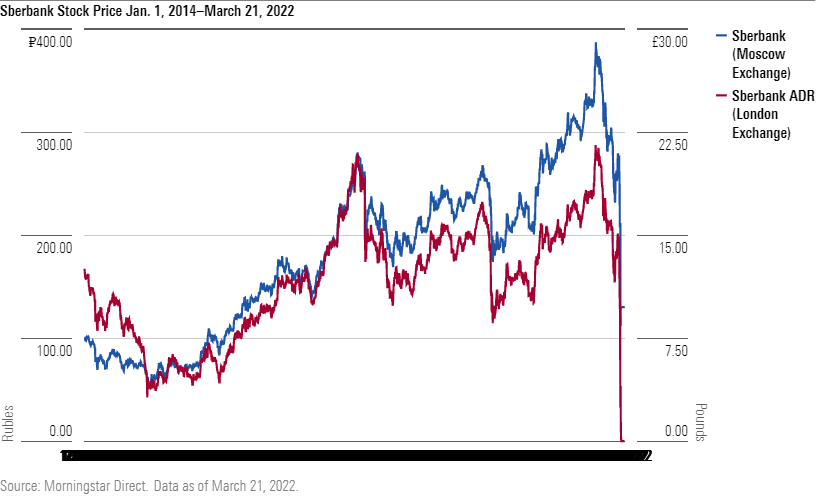

As it turned out, these portfolio managers accurately assessed the likelihood of those headline risks impacting the stock. When Sberbank's share price plummeted to near zero in late February 2022, it wasn't because Putin had targeted Sberbank's management, or the management had acted in an irresponsible manner, or Russia's central bank had implemented unreasonable policies.

However, we now know that there were other, even more serious risks. Share prices of all Russian stocks plummeted when its military launched a wide-ranging invasion of Ukraine and countries around the world responded by imposing such harsh sanctions that they quickly enveloped a domestically focused retail bank without clear military importance.

Some might say that these events constitute a black swan, the term popularized by Nassim Taleb to describe occurrences that were literally unprecedented and thus could not have been foreseen. The current disruption comes close but may not quite meet the standard. Russia already had attacked Ukraine in 2014, by aiding separatists to seize control of a chunk of territory in the east and by taking over and annexing Crimea as well. The U.S. and other countries applied sanctions in response. That said, the scale of the current invasion and sanction regimes far exceeds the level of those events. (Perhaps it therefore qualifies as a gray swan.)

In any case, Taleb's point wasn't to excuse investors who failed to protect against a black-swan event. He thought that unforeseen crises happen often enough that investors should anticipate their occurrence and take measures against them.

One could argue that the portfolio managers did follow that advice, by limiting their Sberbank weighting to less than 2% of assets in almost every case, even though they considered it a great business. (Whether they should have sold out entirely in the couple of months preceding the invasion when that outcome became more likely is a topic for another day. Some did trim their Russia holdings; others may have done so without publicly disclosing their moves.)

Or one could take the opposite view and say that the most prudent way to protect against black-swan events in Russia would have been to avoid that market altogether.

Dealing With the Risks

It would be unfair to contend that all investors, whether portfolio managers or everyday shareholders, should focus primarily on avoiding the fallout from unprecedented, potentially cataclysmic occurrences. We would never invest anywhere. In a recent column, some of my Morningstar colleagues along with outside commentators took a sweeping approach, recommending that investors steer clear of countries with autocratic leaders.

David Herro, manager of Oakmark International OAKIX, says he's avoided Russia in particular because it lacks transparent accounting practices and adequate legal protections for minority shareholders.

However, managers of emerging-markets funds must deal with the universe they're given. It was certainly possible to exclude Russia, with its rather small index weighting (3.5% of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index prior to the invasion), though doing so would entail a different variety of risk. A small percentage of funds in the diversified emerging-markets category did have zero stakes in Russian stocks in their latest portfolios issued before Feb. 24.

However, trying to exclude all countries with autocratic leaders would present quite a dilemma for emerging-markets managers. China made up 32% of the MSCI Emerging Markets Index at year-end 2021, and that figure was even larger--greater than 40%--a few years earlier. An emerging-markets manager who excludes that huge market--and perhaps also India (12.5% of the index) and Brazil (4%), whose leaders face elections but are widely considered to have autocratic tendencies--would be hard-pressed to assemble a well-diversified portfolio of appealing companies. In fact, more than half of the remaining index weight consisted of South Korea and Taiwan, which some index providers and portfolio managers no longer classify as emerging markets.

There's Another Option

While emerging-markets managers thus face tough choices given the limitations of their mandate, we ordinary investors have another option. We can choose not to own a dedicated emerging-markets fund at all. And that wouldn't mean excluding all emerging-market stocks. We can own broad international funds whose managers have the leeway to own many emerging-markets stocks, or a few, or none, in whichever market they choose, depending on what they consider appropriate at the time. This is one way to deal with the challenging, complicated risks of a potentially rewarding subset of stocks and markets.

Morningstar associate analysts David Carey and Sachin Nagarajan contributed to this article.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/657019fe-d1b1-4e25-9043-f21e67d47593.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WJS7WXEWB5GVXMAD4CEAM5FE4A.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/NOBU6DPVYRBQPCDFK3WJ45RH3Q.png)