Bond Investors Facing Worst Losses in Years

With inflation still running hot, bond prices are sliding as the market looks for faster Fed rate hikes.

Investors may be in for a rude surprise when they look at their bond investments come quarter-end.

The normally sleepy bond market is seeing some of its worst losses in years as the markets once again reset expectations for how quickly the Federal Reserve will be raising interest rates.

The latest back-and-forth around how much the Fed will raise rates has the bond market shifting into a "higher, faster" mode for interest rates thanks to inflation remaining elevated longer than most investors expected, a dynamic worsened by the spike in oil prices after Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

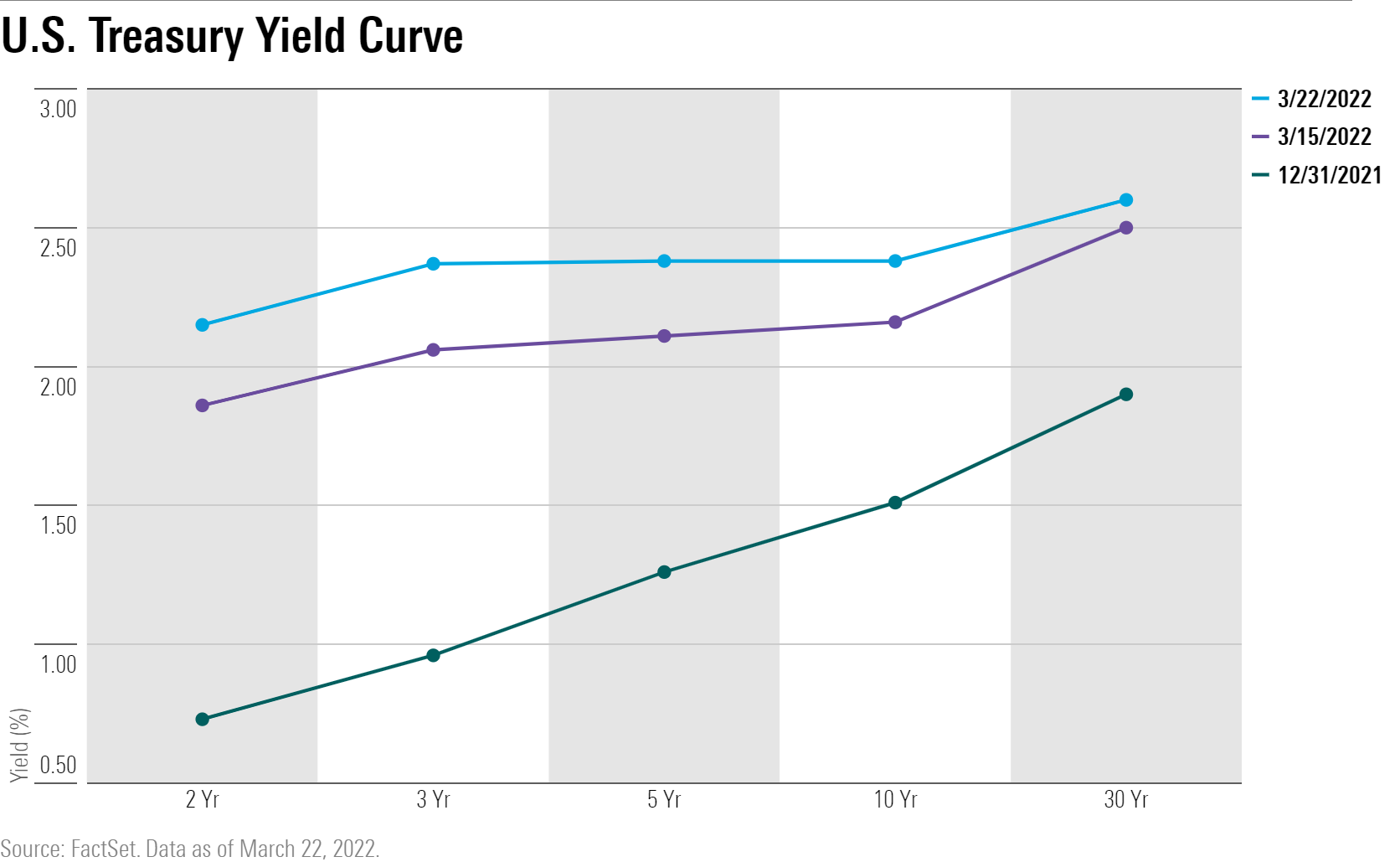

The result is that yields--which move in the opposite direction of bond prices--have been rising at their fastest pace in years. In just the past week, the yield on the U.S. Treasury 10-year note has jumped to 2.32% from 2.19%, and is up from 1.63% at the start of January. At the same time, the yield on the U.S. Treasury 2-year note has risen to 2.11% from 1.97% a week earlier, and 0.79% on Jan. 3.

This is translating into pain for bond investors in their portfolios.

The $16.5 billion iShares U.S. Treasury Bond ETF GOVT is down 5.90% for the year to date, falling more than 3% in the past month and more than 1% in the past week. A broader tracker of the bond market, the $305 billion Vanguard Total Bond VBMFX, is down 6.4% this year, with a 2.7% decline in the past month. For comparison, the worst year in history for VBMFX was a 2.66% decline in 1994.

“Volatility in the bond market is very high,” says Eddy Vataru, lead portfolio manager of Osterweis Total Return OSTRX.

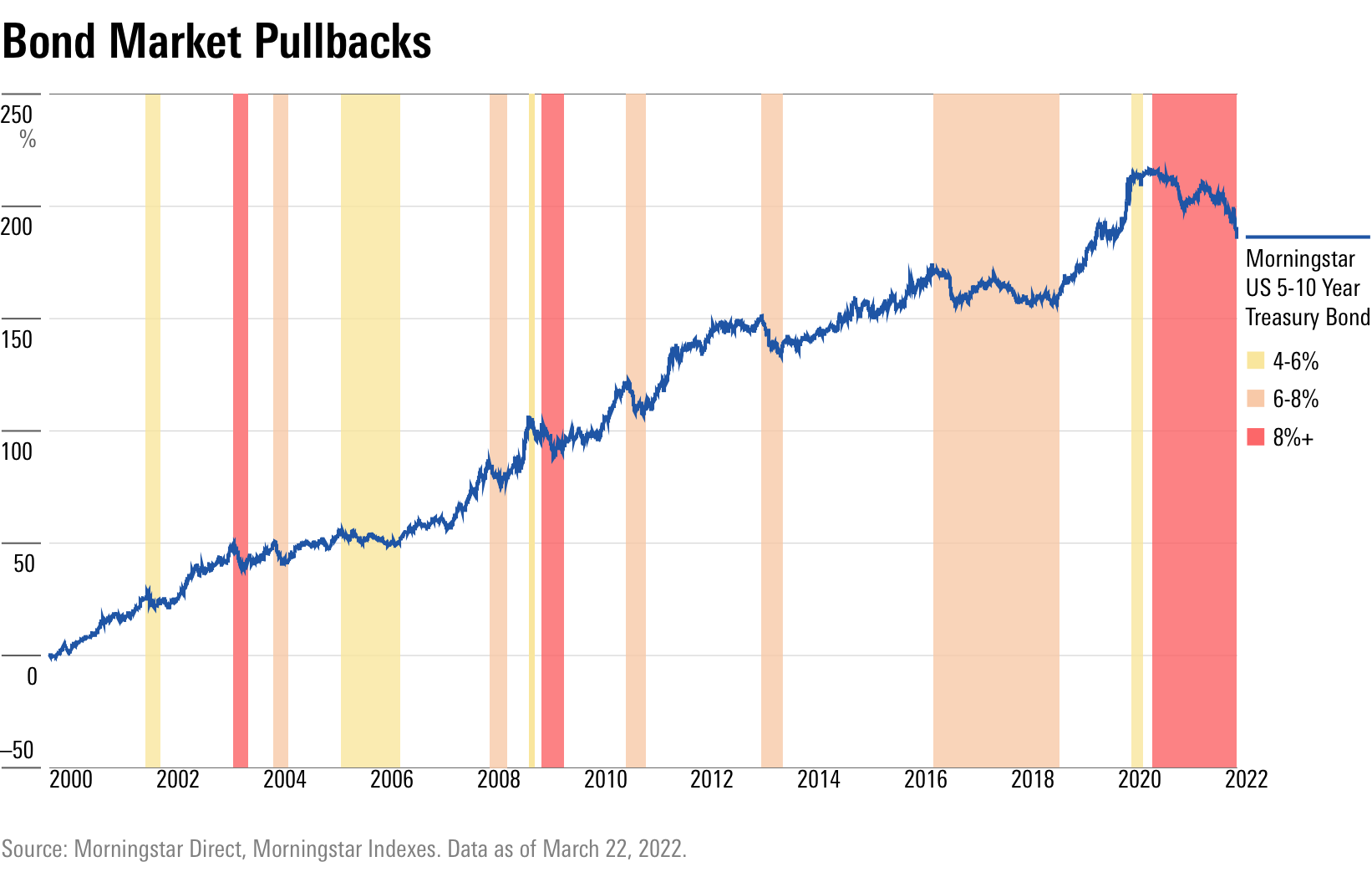

These declines are some of the worst that the bond market has seen in many years. For example, the Morningstar US 5-10 Year Treasury Bond Index is down 5.7% so far in 2022 and has lost some 9.6% since its last peak in August 2020, the largest drawdown in its history.

The rout in Treasuries that began Monday followed more hawkish inflation-fighting remarks by Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, less than a week after the central bank raised the federal-funds rate by 0.25 percentage points. That was the first rate increase since December 2018.

In a speech to the National Association for Business Economics, Powell said inflation "is much too high," and that the Fed would move "more aggressively by raising the federal-funds rate by more than 25 basis points at a meeting or meetings" if the central bank deemed it appropriate.

Powell also signaled there would be a series of similar-sized hikes coming through the duration of the year as it seeks to bring down inflation without tipping the economy into recession.

"There’s a heightened sensitivity in the market to Fed-speak," says Vataru. "The rhetoric is very hawkish, and the bond market is finally coming to grips with it and repricing."

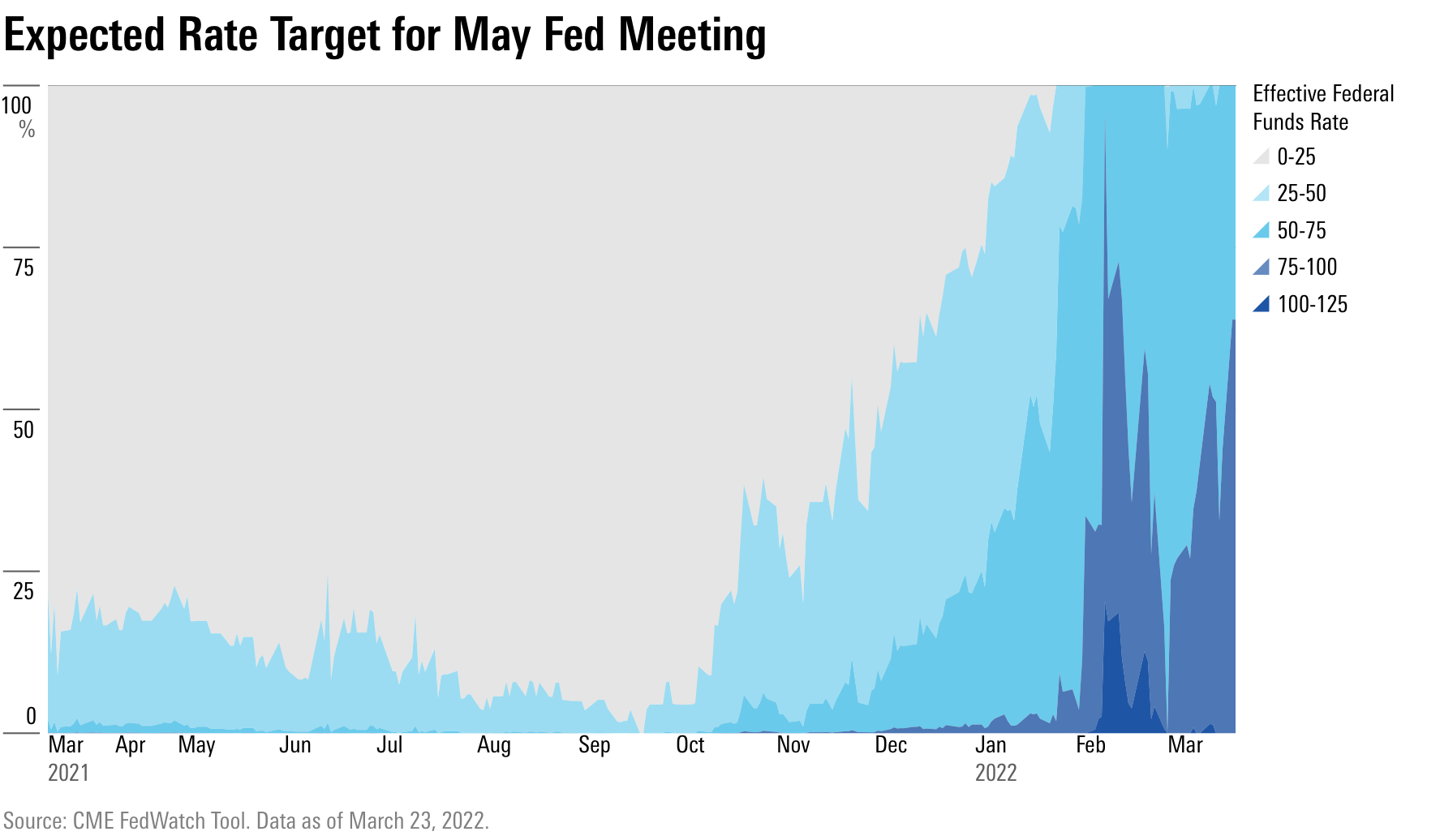

In response to Powell's comments, the market began pricing in a more aggressive pace of interest-rate increases. Expectations shifted from a consistent series of 25-basis-point rate hikes over the course of the year to 50-basis-point increases in May and June, along with continued hikes over the course of 2020. Wall Street firms, such as Goldman Sachs, are now calling for 50-basis-point increases in the funds rate at the next two meetings.

"The market is implying the Fed will move faster and at a higher rate of 50 basis points potentially at the next couple of FOMC meetings," says David Sekera, Morningstar's chief U.S. market strategist.

Powell also reiterated that the Fed would begin to shrink its $9 trillion balance sheet this year, which would result in a further tightening of monetary policy. This so-called "quantitative tightening" would reverse the impact of the Fed’s bond-buying program--"quantitative easing"--employed to push bond market yields down during the pandemic recession and help stimulate the economy.

With its buying program, the Fed was essentially the largest purchaser of bonds in the market. It was only two weeks ago that the Fed stopped buying Treasury bonds.

"We are back to more of a free market for Treasuries, unencumbered by Fed purchases,” says Jason Trennert, chairman and chief executive at Strategas. It takes not having the Fed's thumb on the scale to "know the true value of the 10-year Treasury."

Powell indicated that more details on the Fed’s thinking around cutting its bond holdings will be available when minutes are released from the most recent meeting of the policy-making Federal Open Market Committee. That is scheduled for release on April 6.

"Based on how much and how fast the Fed decides to unwind the balance sheet could have a significant impact on the supply-demand characteristics of the bond markets," says Sekera.

Complicating the Fed’s policy decision making is the war in Ukraine, which has accelerated inflationary pressures by disrupting the energy, metals, and agricultural markets. Normally considered a safe haven in times of geopolitical turmoil, Treasuries are now caught in the crossfire of a "calamity that’s driving inflation through the roof and trumping the flight-to-quality nature of the asset class," Osterweis’ Vataru says.

There is also widespread agreement that the Federal Reserve waited too long to address inflation threats.

"Quantitative easing was way too much and went on for way too long," says Vataru. "Rates can and should be higher."

He believes the Fed can possibly steer clear of a recession and engineer a stable, less-disruptive outcome by focusing more on reducing the balance sheet, whose growth was the main culprit behind ballooning inflation in his estimation, in combination with rate hikes.

One of the fundamental issues dogging the bond market is uncertainty about how high rates will actually need to be raised.

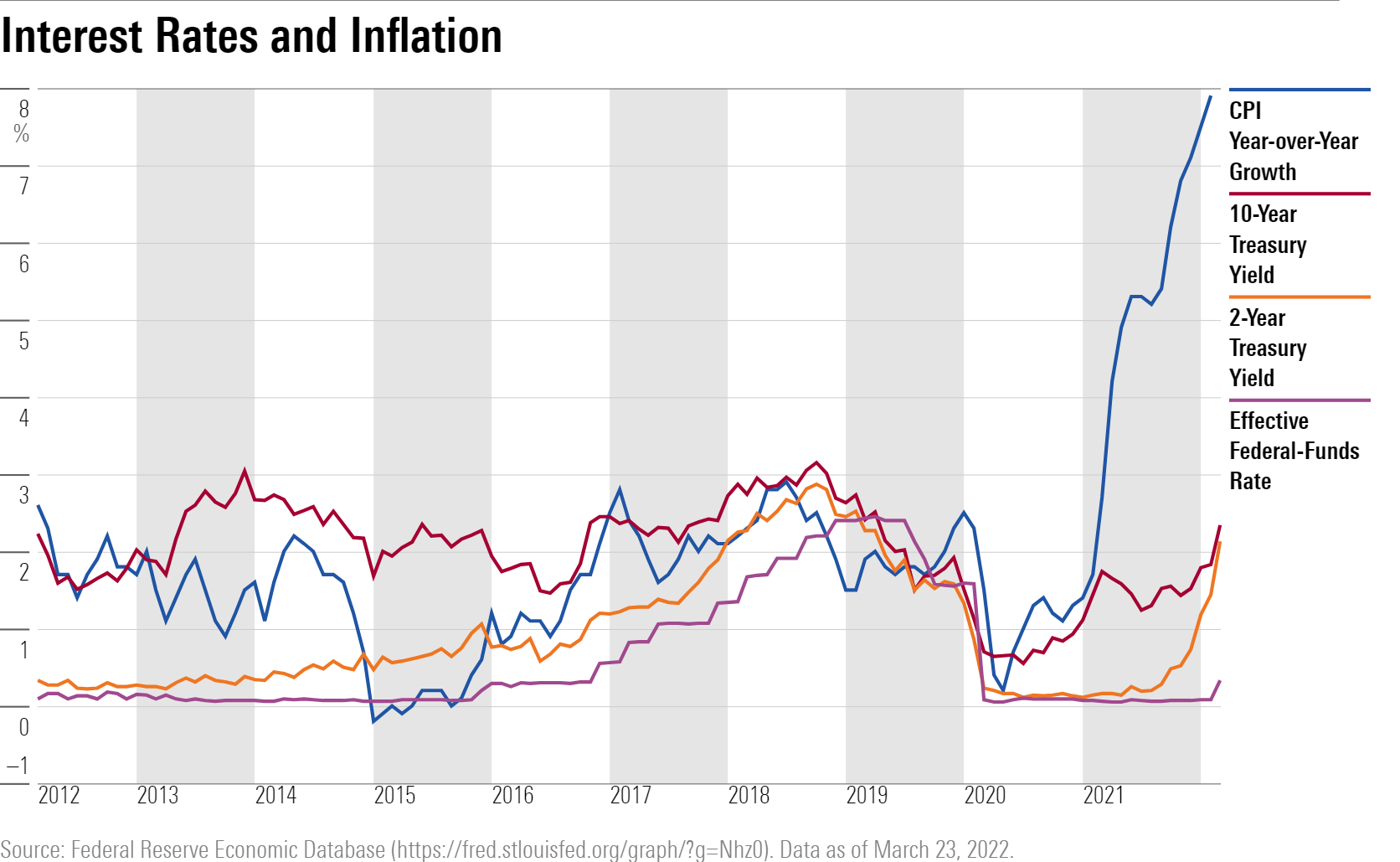

Fed policy has been exceptionally accommodative, keeping rates very low as a way to boost the economy during the pandemic. The Fed has set a 2% target rate for inflation and to meet its goal of achieving full employment and price stability. With inflation running at about 8% that is seen as too low and off target.

As a judge of where the Fed needs to get to, investors try to assess what the bank’s “neutral rate” should be, which the central bank defines as an interest rate level that doesn't accelerate growth and doesn't crimp demand.

"It's unclear what the neutral rate is," Vataru says. "It's a slightly untethered market."

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)