Does Your Portfolio Need Private Equity?

Despite the potential for higher returns, the investment case is mixed.

Private equity has been a hot topic lately. Many institutional investors expect lower returns from traditional stocks and bonds over the next 10 to 20 years and are looking further afield to help fill the gap. There’s some evidence that private equity can provide higher returns, but for most individual investors, the negatives probably outweigh the positives.

Hunting Ground for Returns

Private equity--a broad category that includes buyout funds, venture capital, and growth equity investment assets that don’t trade on an exchange and aren’t SEC-registered--is a popular hunting ground in the search for higher returns. For example, the California Public Employees' Retirement System recently raised its private equity allocation target to 13% of assets from 8%. Many other state and local pension funds have made similar increases.

Another reason behind the growing interest in private equity: Companies are remaining private longer. The number of publicly traded companies in the United States has significantly declined over the past couple of decades. At the same time, the private market is home to about 1,000 unicorns--companies valued at $1 billion or more that are available only to select investors through private channels.

In addition, the U.S. Department of Labor issued a June 2020 information letter indicating that defined-contribution plans can offer private equity as an investment option as long as it is part of a broadly diversified and professionally managed portfolio, such as a target-date, target-risk, or balanced fund. (It later clarified that private equity may not be suitable for smaller plans that lack the resources needed to evaluate private equity.)

Meanwhile, the lines are blurring between venture funds and private equity specialists on the one hand and traditional asset-management firms on the other. Sequoia Capital, one of the largest and most successful venture capital firms, recently announced that it plans to restructure its operations to launch an open-end fund and become a registered investment advisor.

On the other end of the spectrum, Vanguard recently expanded its partnership with HarbourVest to give some of its clients the option of investing in private equity, as long as they meet the requirements for being both a qualified and an accredited investor.

Are Returns Really Higher?

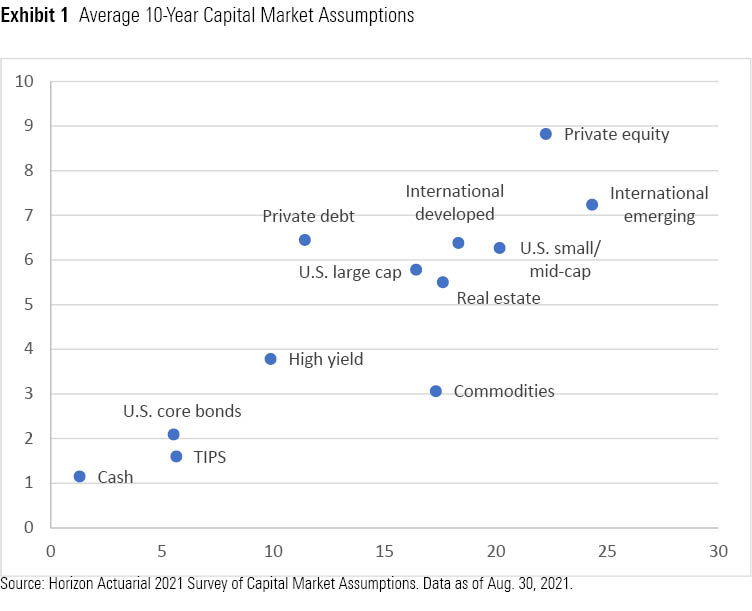

As shown in Exhibit 1, institutional investors have high expectations for private equity returns. Based on the Horizon Actuarial 2021 Survey of Capital Market Assumptions, return expectations for private equity over the next 10 years (averaging 8.8% annualized) are higher than for any other major asset class. Whether returns will meet those expectations is an open question.

For one thing, measuring returns for private equity is not straightforward. Private equity funds typically report returns using an internal-rate-of-return calculation that incorporates the beginning and ending values of the fund as well as interim cash flows. One drawback to this method is that it assumes investors can reinvest any interim cash flows at the same rate of return, which is usually not the case. In contrast to total-return calculations that are compliant with global investment performance standards, internal rate of return does not have a single standard calculation method and can also be subject to manipulation by “gaming” the timing of cash flows.

In addition, reported IRR figures are subject to reporting lags due to the manual process of determining valuations on private companies, making it difficult to compare private-market assets and other parts of a portfolio in a timely fashion. Since late 2008, the Financial Accounting Standards Board has required private equity firms to value their assets at fair market value each quarter. However, this still takes time, with reports usually coming out more than a month after quarter-end. On the venture capital side, IRR measures can also be heavily influenced by valuation levels at the time of exit. Many venture-funded firms were able to exit at steep valuations during 2020 and 2021, contributing to eye-catching recent returns for venture capital funds.

To address some of the shortcomings of IRR, academic researchers Steve Kaplan [1] and Antoinette Schoar developed an alternative measure known as public-market equivalent returns in 2005. The PME uses the total return of the S&P 500 as a discount rate for all cash inflows and outflows and measures the fund's net lifetime return relative to that of the S&P 500. For example, a PME of 1.2 would indicate that the fund outperformed the benchmark by 20% on a cash basis (not annualized), while a PME of 0.95 would indicate that it underperformed by 5%. Some researchers have also adapted the PME measure to incorporate other market benchmarks.

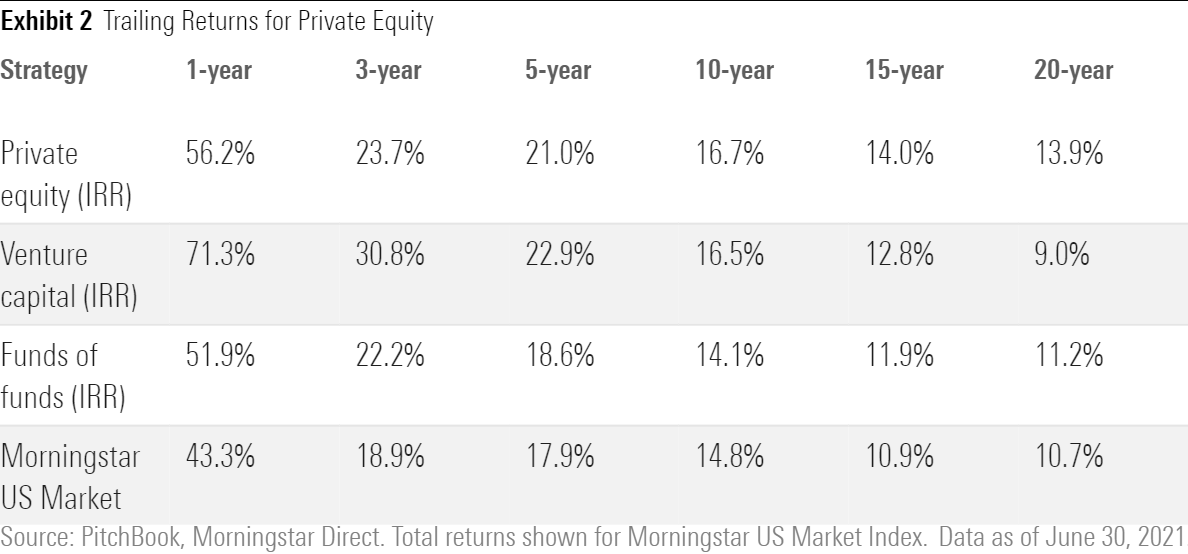

With those limitations as a caveat, there’s some evidence of above-average performance for private equity (Exhibit 2).

PitchBook, a Morningstar company that tracks private markets, estimates that PME returns for private equity funds with vintage dates from 1996 through 2020 averaged 1.22 as of June 2021 using the S&P 500 as a benchmark, while venture capital funds averaged a PME of 1.29 over the same period.

Wide Range of Returns

However, these benchmark averages don’t show the full picture. Academic research has found a wide dispersion of returns for private equity versus their public counterparts, although there are signs that it has narrowed over time. For example, the gap between the top- and bottom-performing quartile of private equity funds spanned about 22 percentage points based on data from PitchBook compared with about 12 percentage points for the large-blend Morningstar Category.

Venture capital tends to have an even wider dispersion of returns. Investors often expect only one or two out of every 10 investments to generate large gains, while the others return capital or fizzle out. As a result, the gap between the top- and bottom-performing quartiles of venture capital funds with a vintage date of 2017 spanned more than 28 percentage points.

These issues make private equity difficult to use effectively. In fact, David Swensen (of Yale Endowment fame) put it bluntly: “In the absence of truly superior fund selection skills (or extraordinary luck), investors should stay far, far away from private equity investments.”[2]

In addition, the venture capital subset of private equity has often been subject to hot and cold performance swings. A 2014 research paper found that venture capital outperformed net of fees for most vintages since 1984 but underperformed during the 2000s.[3]

Buyout funds, which typically use debt to buy established companies and then step in to improve their operations and underlying cash flows, have also generated inconsistent returns. After periods of high returns, investors often pour money into the space, which can result in increased competition for deals and, thus, higher entry prices, making it more difficult to get to highly profitable exits. As a result, higher inflows to buyout funds often lead to lower subsequent returns.[3]

High Barriers to Entry

The large dollar amounts required to invest in private equity are one of the biggest negatives. At a minimum, investors must meet accredited investor requirements, which generally require annual income of at least $200,000 (or $300,000 joint income) for the two previous years as well the expectation that income will reach the same level in the current year. Investors can also be considered accredited investors if they have a net worth (either individually or with a spouse) of at least $1 million or have certain roles with the company issuing unregistered securities; that is, a private equity firm. Some private equity vehicles may require investors to meet qualified investor requirements, which require investment assets of at least $5 million.

Even for investors meeting these requirements, investment costs are far higher than those for publicly available investment vehicles. Private equity funds typically charge a 2% management fee as well as additional performance fees equal to 20% of profits.

Funds of funds offer more diversified exposure to private equity, but they also involve an additional layer of fees. The typical private equity fund of funds collects 1% in management fees and 5% in incentive compensation[4], which might seem low for private equity exposure, but those costs are in addition to the fees on the underlying funds.

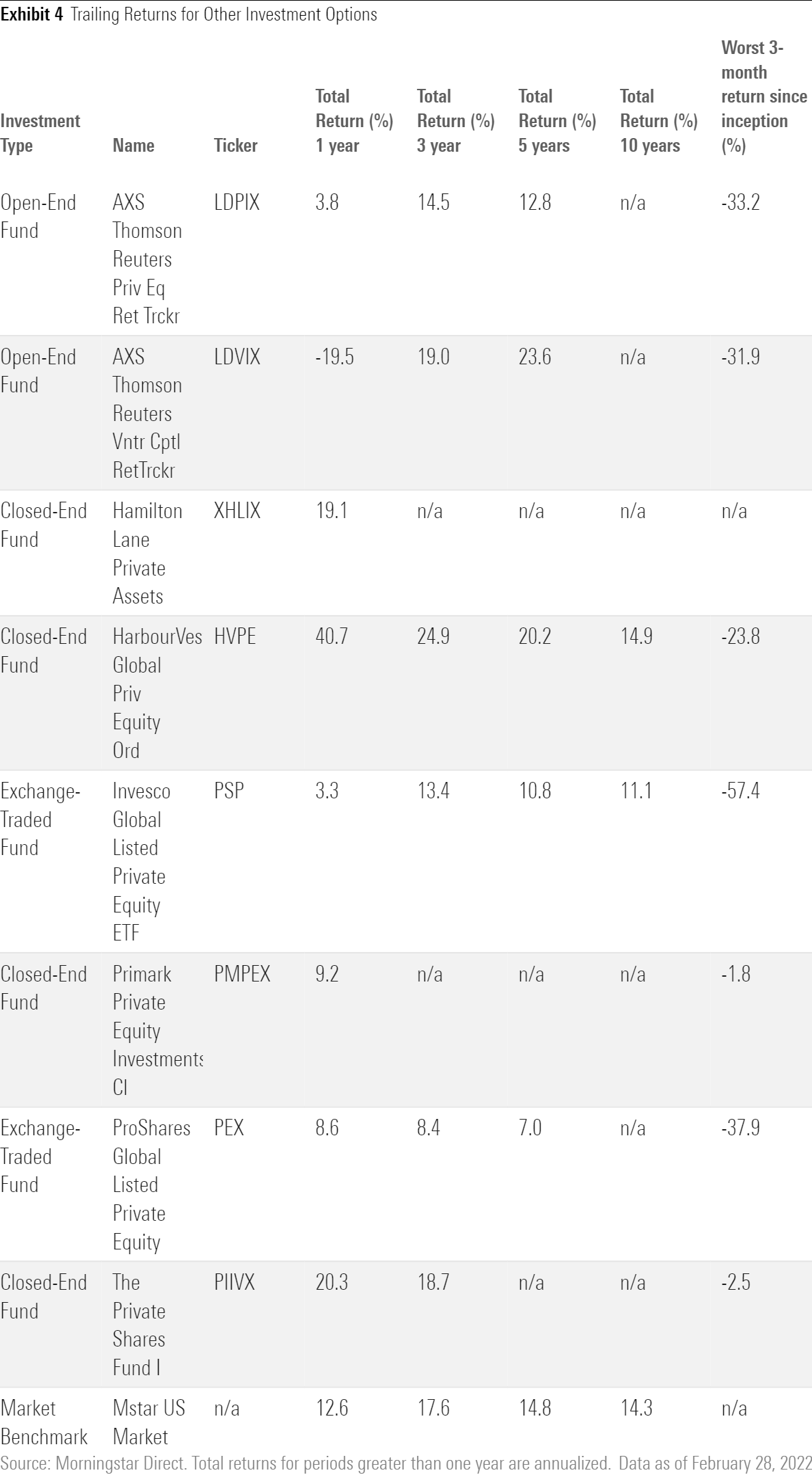

Other Investment Options

For most individual investors, direct investment in private equity is likely out of reach. It typically requires a minimum direct investment of at least $1 million, and an investor would need closer to $20 million to create a diversified private equity portfolio. This effectively limits direct private equity exposure to an elite group of ultrawealthy individuals or family offices.

However, individuals at lower wealth levels have other options for private equity exposure (as long as they meet the accredited or qualified investor requirements). As mentioned above, Vanguard is now offering exposure to a private equity fund managed by HarbourVest to some of its customers. (Vanguard won’t disclose details about the fund, including the required minimum investment.)

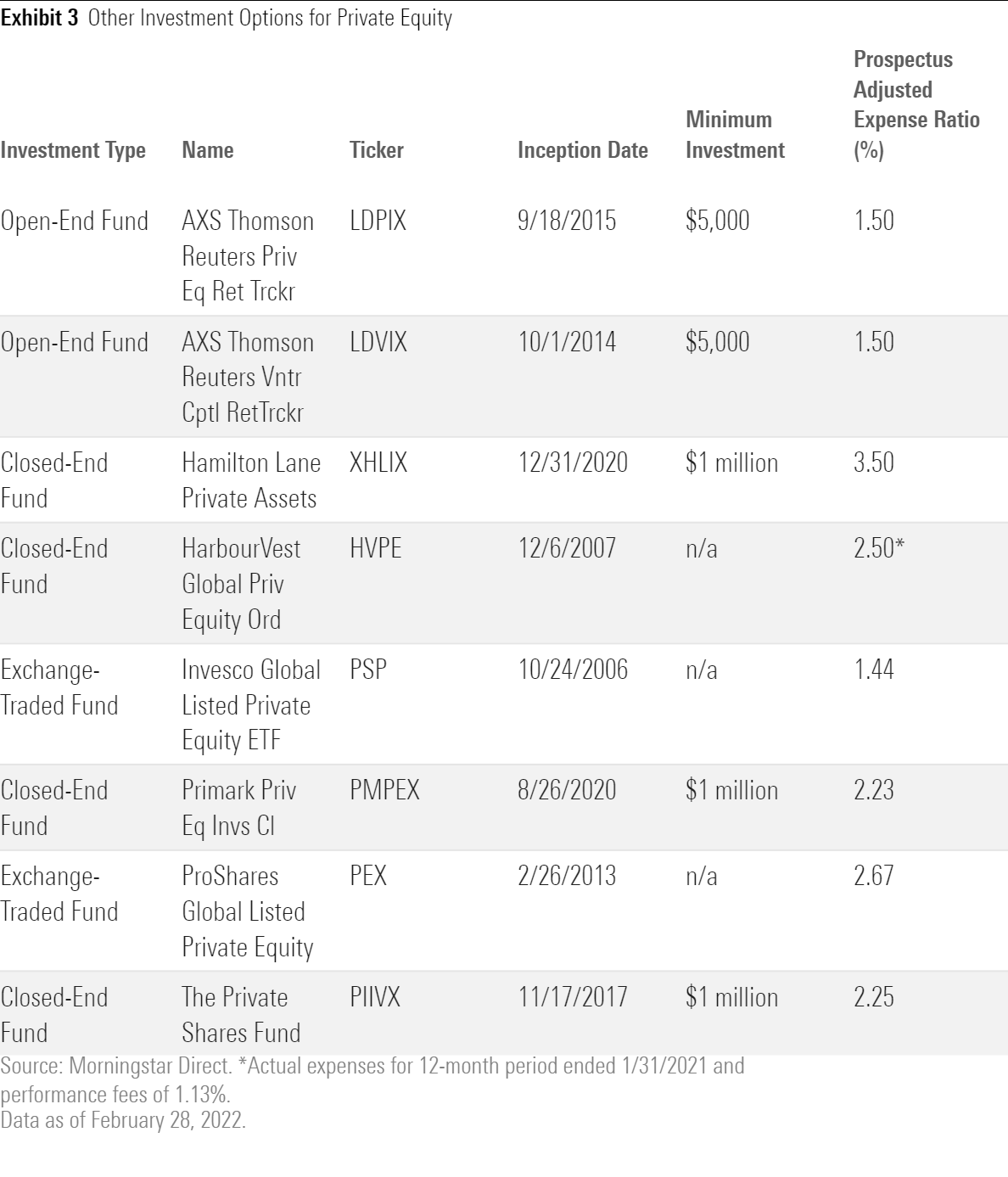

HarbourVest offers at least one other fund (HarbourVest Global Private Equity HVPE), but approximately 70% of its shareholders are based in the United Kingdom, and the majority of trading volume is in sterling. The fund, like the other two closed-end funds shown in Exhibit 3, is structured as a closed-end interval fund. These funds only allow shareholders to redeem a portion of their shares on a fixed schedule, typically quarterly. As a result, they’re relatively illiquid, a trait that also characterizes private equity in general.

This lack of liquidity is the flip side of the coin for what makes private equity popular (it’s more stable over shorter periods because it’s illiquid and thus slower to revalue), but some investors will not be able to handle being denied access to their funds when the going gets tough. In addition, closed-end funds often trade at a premium or discount to their underlying net asset values. This adds another layer of risk; closed-end fund returns can often diverge from the returns on their underlying holdings by a wide margin.

The two AXS funds, which are structured as open-end funds, are the most widely available to individual investors but don’t invest directly in private equity or venture capital. Instead, they use a combination of public-equity investments and total-return swaps to track their benchmarks, the Refinitiv private equity and venture capital indexes. Over time, both funds have tracked their benchmarks fairly closely.

The two exchange-traded funds shown, which track listed private equities, are also relatively accessible to individual investors. However, one drawback is that as an asset with daily trading activity, listed private equity is inherently more volatile than direct private equity investment.

Another key difference with listed private equities is that they provide exposure to a private equity company’s results, not a fund’s results. A private equity company may offer lots of funds that are generating fees and carried interest; the valuation of the firm is based on these cash flows rather than the underlying fund investments that make up a private equity fund’s return.

Private equity firms were particularly hard-hit during the global financial crisis, when many pension and endowment funds had to sell private equity assets at fire-sale prices. Invesco Global Listed Private Equity ETF PSP, for example, suffered a 64.8% loss in 2008. This makes it abundantly clear that despite the liquidity advantages of listed private equity, it’s not for the faint of heart.

As mentioned above, U.S.-based defined-contribution plans can now include private equity exposure as part of a diversified plan offering such as a target-date fund. To date, though, few if any plans have expanded their lineups to include private equity.

Role in Portfolio

Private equity is sometimes touted as a portfolio diversifier, but it’s ultimately just equity, not a separate asset class. Partly because of the return-measurement issues discussed above, it’s difficult to pin down an exact number for private equity’s correlation with publicly traded stocks. However, several researchers have found evidence that private and public equities generally tend to move in the same direction. J.P. Morgan, for example, estimates that a major private equity index has had a correlation of 0.9 with publicly traded stocks from June 2008 through June 2021, although venture capital correlations have been lower.

Not only have correlations generally been high, but beta has been even higher. AXS Thomson Reuters Private Equity Return Tracker LDPIX, for example, has had an equity market beta of 1.66 over the past three years, while its venture capital sibling has had a beta of 1.45. This suggests that private equity and venture capital should be thought of mainly as leveraged equity exposure, not as portfolio diversifiers.

The other major argument for including private equity from a portfolio perspective is that it accounts for a significant portion of the global opportunity set. Based on data from the Chartered Alternative Investment Analyst Association, private equity assets totaled about $6.5 trillion globally as of year-end 2020 compared with public equity assets of $67.4 trillion and total assets (including fixed income and real estate) of $153.3 trillion. Investors who want to match the “market basket” portfolio would therefore want to carve out about 4.2% of their investable assets for private equity.

Conclusion

The strongest argument for including private equity in a diversified portfolio is the potential for better long-term returns. But while higher returns are far from guaranteed, the complexity, risk, and steep price tags inherent in private equity are a given. Ultimately, the fact that private equity remains out of reach for most individual investors is probably a good thing.

[1] Steve Kaplan is a member of Morningstar's board of directors. [2] Swensen, D. 2009. Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment (New York: Free Press), P. 224. [3] Harris, R., Jenkinson, T., & Kaplan, S. 2014. "Private Equity Performance: What Do We Know?" Journal of Finance, Vol. 69, No. 5, P. 1,851. [4] Wiek, H. & Carmean, Z. 2020. "Primer on Private Market Access Points." PitchBook Analyst Note. April 23.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/URSWZ2VN4JCXXALUUYEFYMOBIE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CGEMAKSOGVCKBCSH32YM7X5FWI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)