Can Bank-Loan Funds Provide Shelter From Rising Rates?

Keep your portfolio afloat during interest rate hikes.

A version of this article previously appeared in the March 2022 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Click here to download a complimentary copy.

On Jan. 26, 2022, the Federal Reserve announced it would likely hike interest rates in March. Stocks and bonds had been in the red since the beginning of the year, and the prospect of higher rates didn’t help matters.

What can investors do to protect their portfolios from the pressure of rising rates? Reducing interest-rate risk might be the most straightforward solution. And few options are as surefire for ratcheting down rate risk than bank loans.

It’s little surprise that many investors have flocked to bank-loan funds in 2022. Mutual funds and exchange-traded funds in the bank-loan Morningstar Category pulled in nearly $9.6 billion in new flows in January, marking 8.2% organic growth versus their combined year-end 2021 assets.

Before following the crowd, investors should get smart about bank loans and the funds that invest in this space. While they can help ward off rate risk, they take on other kinds. Also, there are ample implementation challenges that can either impede these funds’ ability to invest successfully in the space or create opportunities for them to add value. Here, I’ll provide investors an overview of what to look out for when selecting from the menu of bank-loan funds.

Bank Loans 101

Bank loans, or leveraged loans, are private loans taken out by companies from banks or a syndicate of lenders. The borrowers often carry credit ratings that are below-investment-grade. As such, they will often offer extra yield to compensate for their credit risk. Almost all bank loans have floating interest rates. Their coupon rates are calculated by adding a predetermined spread over a reference interest rate such as Libor or SOFR. These coupons are reset regularly in response to fluctuations in market interest rates, typically every 30–90 days. This floating-rate feature substantially reduces their sensitivity to interest-rate risk, making them an attractive asset in moments when interest rates are rising. These loans also typically enjoy a more-senior position in their issuers’ capital structure relative to traditional bonds. They are often senior-secured, giving them claim to specific assets on the borrower’s balance sheet in the event of a default. These features improve the loans’ recovery rate in the event of default.

From the perspective of the borrowers, issuing unsecured bonds to raise capital will likely mean paying its creditors higher interest rates. Being higher in issuers’ capital structure and having the backing of specific assets make bank loans a means of borrowing at a relatively lower cost. Borrowing directly from financial institutions also allows companies to further customize the terms of their loans, allowing for prepayment without incurring significant penalties, for instance.

So, What’s the Catch?

There’s no such thing as a free lunch, and bank loans are no exception. In exchange for all but immunizing themselves from interest-rate risk, investors in bank loans assume considerable credit risk. While these loans’ structures can improve recovery rates relative to more-junior, unsecured debt, borrowers’ creditworthiness and the quality of its assets will influence performance.

Beyond borrowers’ credit ratings, there are other important items to note when evaluating credit risk. First, the degree of protection from these loans’ seniority varies according to the size of subordinated bonds or loans below it. The fewer of these subordinated tranches there are to absorb losses, the less seniority matters. Thus, recovery rates among loan-only borrowers are often lower than those among issuers with both loans and bonds in their capital structure.

Second, the terms of the loan matter. In recent years, a large portion of new senior loans have been covenant-lite. This generally means that there are fewer terms in place to protect lenders. Most often that means forgoing maintenance covenants that subject borrowers to regular financial tests. This could reduce recovery rates in the event of a default. The prevalence of covenant-lite loans has increased in recent years, as loose lending markets have made the supply side of the market more competitive. Investors might receive higher yield on covenant-lite loans, but that is compensation for taking on greater credit risk.

Beyond credit risk, liquidity risk also looms large in this market. These loans trade over the counter and tend to be thinly traded, making them expensive to trade. And unlike most bonds, the settlement process for senior loans can be manual and drawn-out, typically taking between seven and 12 business days on average.

Implementation Hurdles

Bank loans’ illiquidity presents challenges for the funds that invest in them--index-tracking funds in particular. These loans’ long settlement periods are at odds with mutual funds’ and ETFs’ daily liquidity needs. Bank-loan fund managers have different means of managing this mismatch. They can keep a portion of their portfolio in cash or liquid securities, accelerate settlement of loan trades, and/or maintain a line of credit to draw from in the event of large-scale withdrawals. The last measure is often a “Break Glass In Case of Emergency” option. In practice, most bank-loan portfolio managers use some combination of the first two. Large managers with strong counterparty relationships can often negotiate advanced settlement, although this is never guaranteed. More commonly, bank-loan portfolios often have cash stakes parked in highly liquid money market funds in order to meet any daily redemption requests. Some will also invest a portion of their assets in relatively more-liquid high-yield bonds or preferred stocks. These are sometimes from the same issuers as those represented in the loan sleeve of their portfolios. While these securities might be more correlated with the senior loans these funds own, they will modify the funds’ risk profile versus owning bank loans exclusively, typically trading lower liquidity risk for marginally greater interest-rate and credit risk.

Fundamental credit research is a must in this market. Whereas the stock market is generally highly efficient, quickly absorbing new information into prices, this is not the case in the loan market. For senior loans in particular, the prevalence of below-investment-grade issuers and the intricacies of loan terms provide ample opportunity for sharp managers to add value. As of the end of February 2022, only two out of the 62 funds in the bank-loan category are index trackers. This is a testament to the challenges of indexing in this illiquid and esoteric segment of the market. Invesco Senior Loan ETF BKLN, one of the two indexed options, is underpinned by a benchmark that includes just the largest 100 issues in the market. While its benchmark’s design fosters liquidity and may prevent outsize credit risk by omitting smaller borrowers, it also leaves out a significant portion of the investment opportunity set. The other index tracker, Highland/iBoxx Senior Loan ETF SNLN, puts in similar guardrails. This leaves plenty of opportunity for active managers to add value.

Active Funds Are Probably Better Here

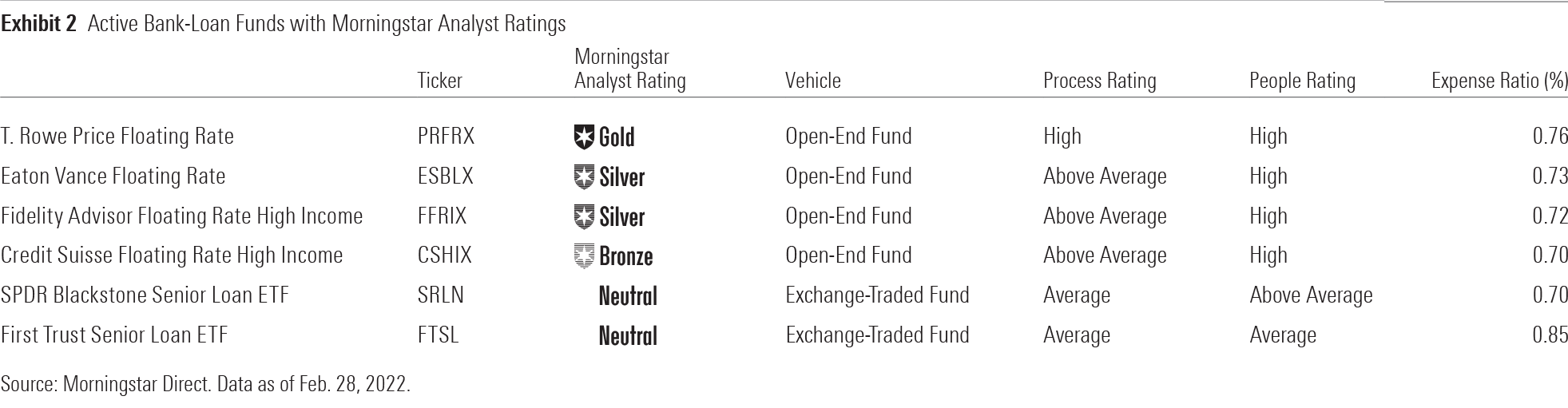

Active bank-loan managers can explore pockets of opportunity that are off limits to the pair of passive funds counted among their competitors. Experienced teams with a deep bench of credit analysts can leverage sound credit research to identify potential gaps between loan prices and their assessment of fair value. They can also make timely tactical allocations to pounce on opportunities or flee from problematic loans. And there’s proof that some savvy managers in this space have done exactly that. For instance, T. Rowe Price Floating Rate PRFRX, the only fund in the category with a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Gold, has historically experienced a 0.1% default rate among the loans in its portfolio compared with around 2% for the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index.

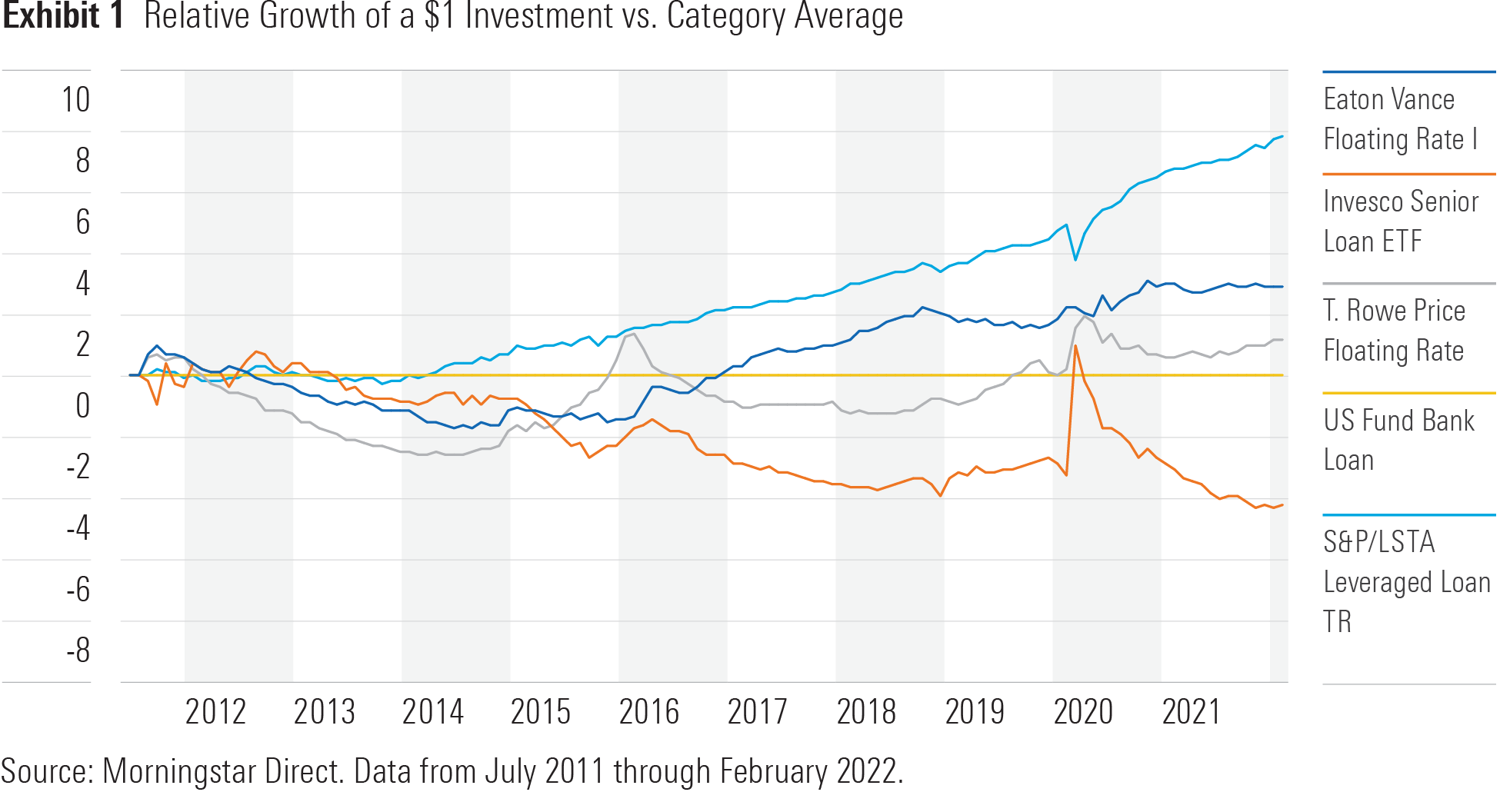

Exhibit 1 plots the relative growth of a $1 investment in the bank-loan category index and several funds versus the bank-loan category average. BKLN’s underperformance speaks to its struggle against a category dominated by more-nimble active peers. It’s notable that even the best-performing funds in the category have lagged the S&P/LSTA Leveraged Loan Index. In this case, the benchmark isn’t a fair comparison, as it isn’t directly investable and doesn’t account for real-world implementation challenges or transaction costs, which would likely take a big bite out of the real-world performance of any fund that tried to track it.

Count bank loans among the few corners of the market where active management isn’t so much a choice as it is a necessity. Exhibit 2 presents a sample of mutual funds and ETFs (active and passive) that carry Analyst Ratings in this category. At this point, it shouldn’t be a surprise that our top-rated funds in this space are actively managed funds boasting a combination of solid teams and processes with a low-cost kicker.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Morningstar, Inc. does not market, sell, or make any representations regarding the advisability ofinvesting in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c00554e5-8c4c-4ca5-afc8-d2630eab0b0a.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/OMVK3XQEVFDRHGPHSQPIBDENQE.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/c00554e5-8c4c-4ca5-afc8-d2630eab0b0a.jpg)