What Do Rising Interest Rates Mean for Diversification?

A rising interest rate environment may increase correlations between stocks and bonds.

Ultra-low interest rates, a result of generous quantitative easing following the 2008 global financial crisis, defined the past decade in capital markets. But that can’t be the case indefinitely, and with the Federal Reserve meeting this week, there could be changes on the horizon.

In our recently published 2022 Diversification Landscape report, we took a deep dive into how different asset classes performed in the past couple of years, how correlations between them have changed, and what those changes mean for investors and financial advisors trying to build well-diversified portfolios.

Given recent strength in the U.S. economy, the Fed has signaled it will raise rates enough to provide the central bank with the leeway to lower rates again should the economy experience a shock. An imminent interest-rate regime shift is under way, but what might that mean for correlations?

Interest Rates Go Up and Down

Generally, correlations between stocks and bonds increase when the market expects borrowing costs to climb. It starts discounting cash flows at higher rates, thereby decreasing the current value of stocks and bonds. That puts more stress on bonds, though, because interest rates directly affect their yields, which make up a large portion of their perceived value. This disadvantages longer-maturity bonds with a lot of duration (a measure of interest-rate risk).

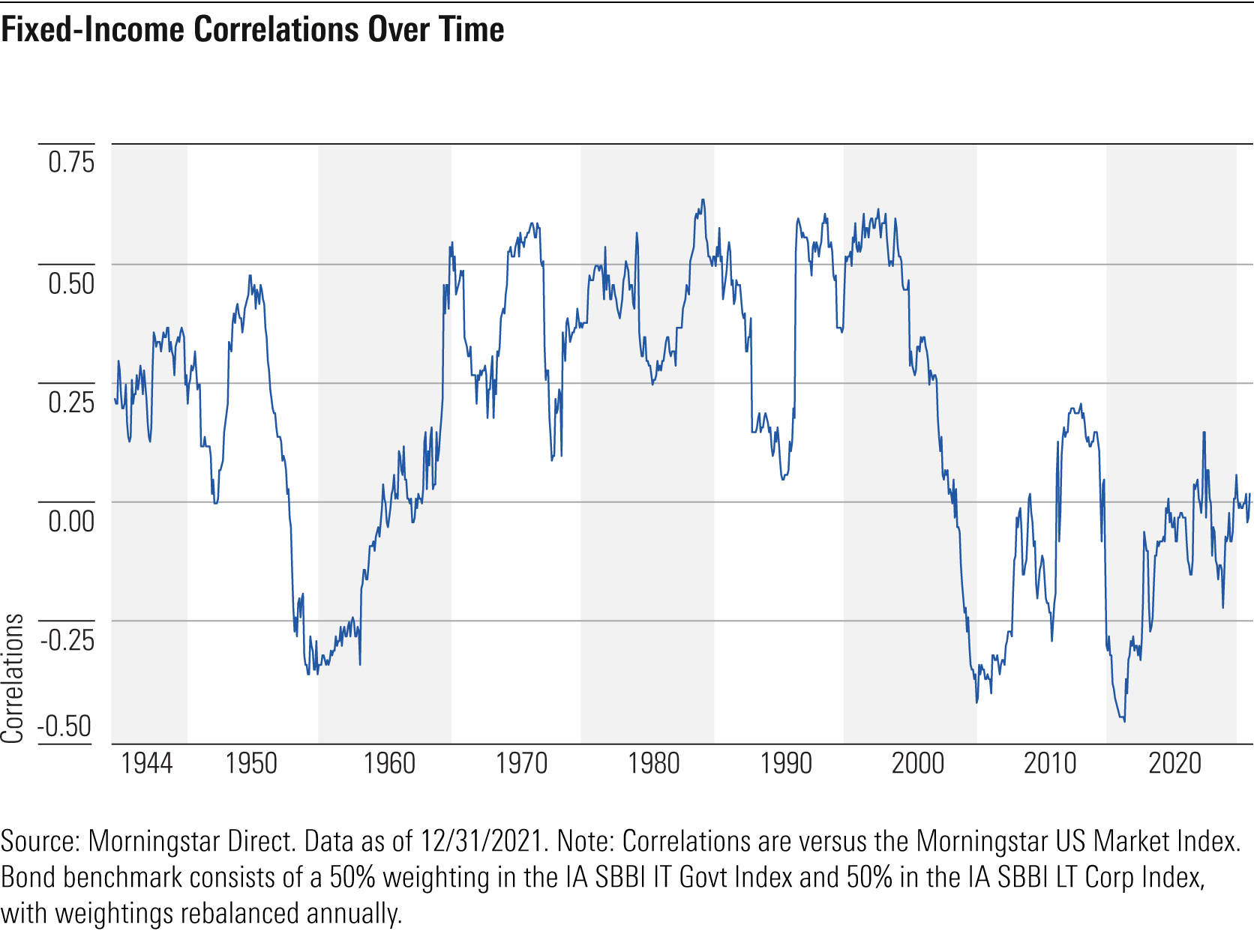

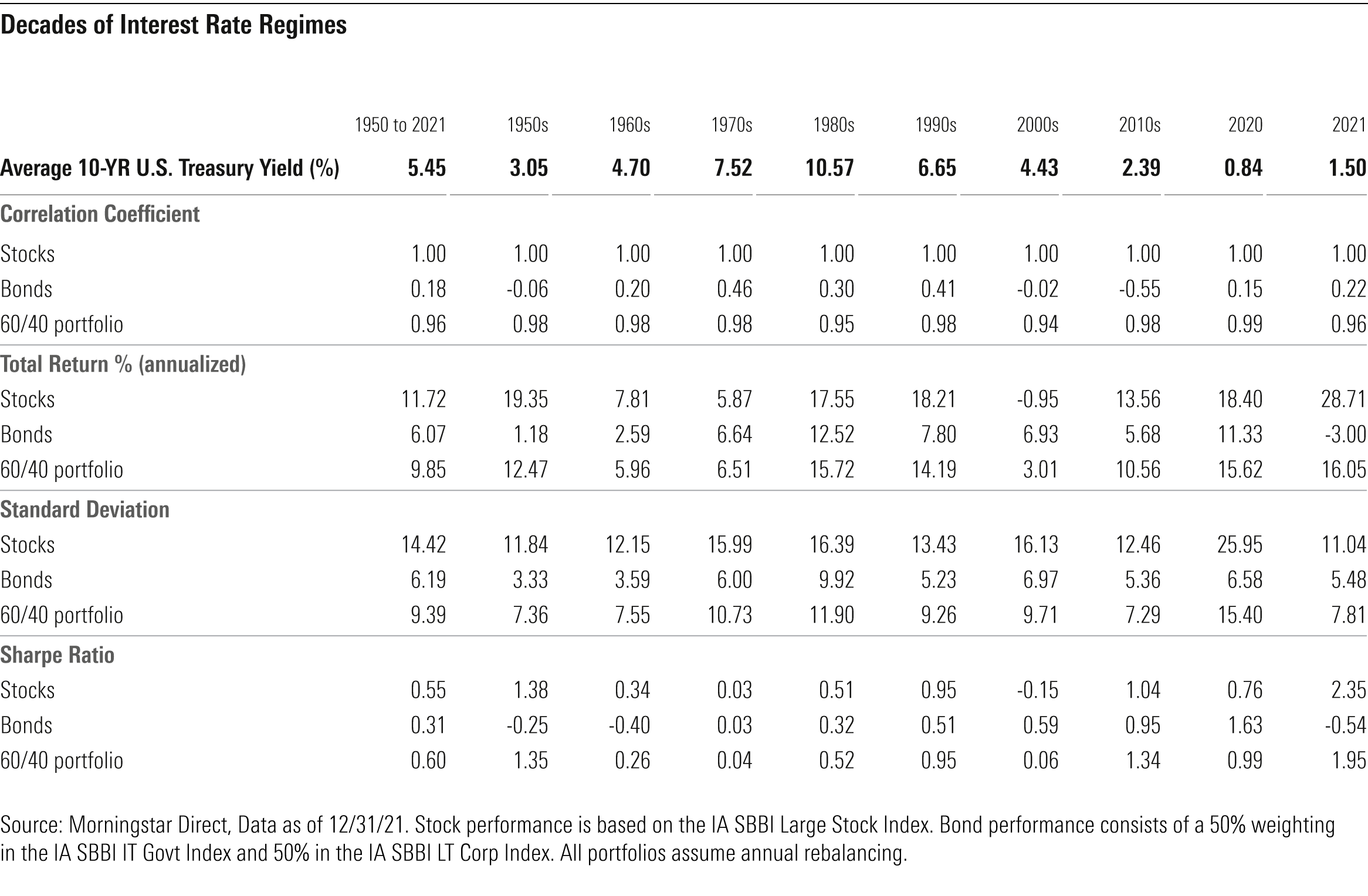

U.S. Treasury bonds serve as safe-haven assets during periods of severe market stress--the source of their negative correlations with stocks in those scenarios. As big interest-rate changes fuel volatility, however, Treasuries’ correlation with riskier assets such as stocks increases. In the past 70 years, across three decades--the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s--the average monthly yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury bond (a practical proxy for interest-rate movements) sat well above the 5.5% long-term average, and the average rolling three-year correlation between stocks and bonds ranged from 0.30 to 0.46.

In contrast, during periods of stable or falling rates, a bond’s duration is an advantage rather than a liability. Then other factors, such as credit quality or liquidity, more heavily influence bond prices. High-quality bonds typically provide greater diversification relative to equities in these periods.

For example, in the 1950s, 2000s, and 2010s the average rolling three-year correlation between stocks and bonds was negative. These are also decades in which the average monthly yield on the 10-year US Treasury was well below the long-term average. The 1960s served as a transition between extremely low- and high-rate periods, with the average 10-year US Treasury yield modestly beneath the long-run average, but yields increased throughout the decade.

In 2020 and 2021, the 10-year U.S. Treasury yield inched upward, accompanied by an increased correlation between bonds and stocks that surpassed the 0.18 average since 1950. Though these correlations remain well beneath the punishing levels experienced in the 1970s and 1980s, the pace of their change illustrates that the current moment could be a pivot point in interest-rate regimes. The Fed's board of governors has signaled as such, and many market participants anticipate anywhere from two to seven hikes in the coming year.

Portfolio Implications

Though rising interest rates lead to increased correlations between stocks and bonds, it’s important to note that anticipating the magnitude of a rate rise and the length of time for the climb is difficult. In fact, many professional investors manage strategies as duration neutral to benchmarks given the difficulty in calling interest-rate changes. But that doesn’t mean there is nothing to do. Nimble investors may mitigate pain from rising rates with some thoughtful planning.

For example, reducing duration by rotating out of longer-duration bonds or funds and into intermediate- or short-duration alternatives will reduce potential volatility when rates spike. It’s also useful to consider further diversifying bond portfolios. Floating-rate funds offer a reprieve from worrying about the direction of rates, albeit with more credit risk than a government bond. Niche exposures, such as to gold or equity market neutral funds, exhibit low correlations to equities and appear attractive when investors want to diversify away from bonds during periods of rising rates; these come with their own cautionary tales, though. Gold prices are heavily influenced by sentiment, and it’s during market crises that gold gains an allure. Equity market neutral strategies are difficult to get right and many offerings have inconsistent performance profiles. Ultimately, niche exposures along these lines are for investors who understand the risks.

One of the easiest ways to combine the prior two recommendations is to consider an actively managed bond strategy. Active bond funds’ theoretically have more flexibility than index funds to sidestep the pitfalls of a rising interest rate environment, but you must choose one with experienced management and the right tools.

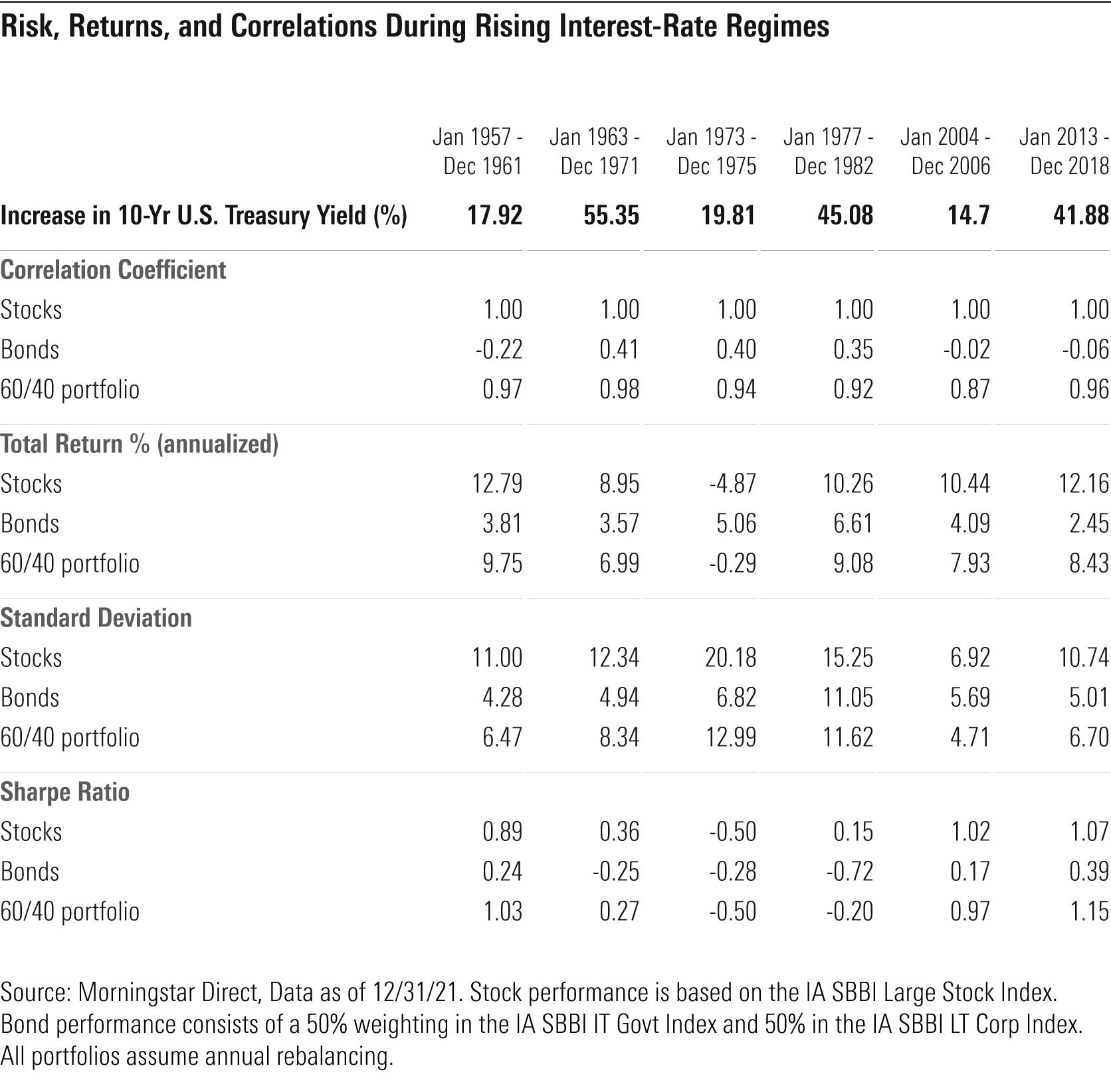

Ultimately, history offers some solace. A rising-rate environment may increase correlations between stocks and bonds, as it did during three of the five interest-rate stress periods listed in the table below (the average three-year rolling correlation is 0.18), but that relationship remained less than 0.5 in all the periods. That means even when bonds are under interest-rate duress, a high-quality bond portfolio continues to provide some diversification away from equities. Most importantly, during longer time horizons, including periods of stable or falling rates, the diversification benefits between stocks and bonds significantly improves a portfolio’s risk-adjusted returns. From 1950 through the end of 2021, the risk-adjusted returns (as measured by a Sharpe Ratio) of a 60/40 portfolio came out ahead of the individual stock and bond components. So rather than obsessing over a period of rate rises, patient investors should trust diversification over the long term.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/bdf88cbd-d3d8-4661-b946-d09f9ffe196b.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/bdf88cbd-d3d8-4661-b946-d09f9ffe196b.jpg)