What a Fed Rate Liftoff Means for Stocks

Historically, stocks have done well in the months after an initial rate increase.

Let the rate hikes begin.

The Federal Reserve is widely expected to begin raising interest rates this week for the first time since 2018, ending a period of extraordinary emergency monetary policy measures that have kept rates near zero for the past two years to stimulate the economy during the pandemic.

With inflation pressures not only remaining high but also broadening, the Fed is widely expected to raise the federal-funds rate by 0.25% on Wednesday.

While this is a significant shift in monetary policy, a rate increase this week has been so well anticipated that stock market observers don’t expect much impact from an expected liftoff. And in fact, history shows that even when the Fed starts raising rates, stocks often head higher.

“Given that this (rate hike) is so expected and widely telegraphed I don’t expect much of a market reaction,” says Paul Hickey, co-founder and president of Bespoke Investment Group, an independent market research firm based in Harrison, New York. “In the next couple of weeks, Fed policy will likely take a back seat to geopolitical concerns.”

The one potential wild card is the Fed’s plans for reducing its holdings of bonds that it purchased in order to push bond market yields down and support the economy during the pandemic-driven recession.

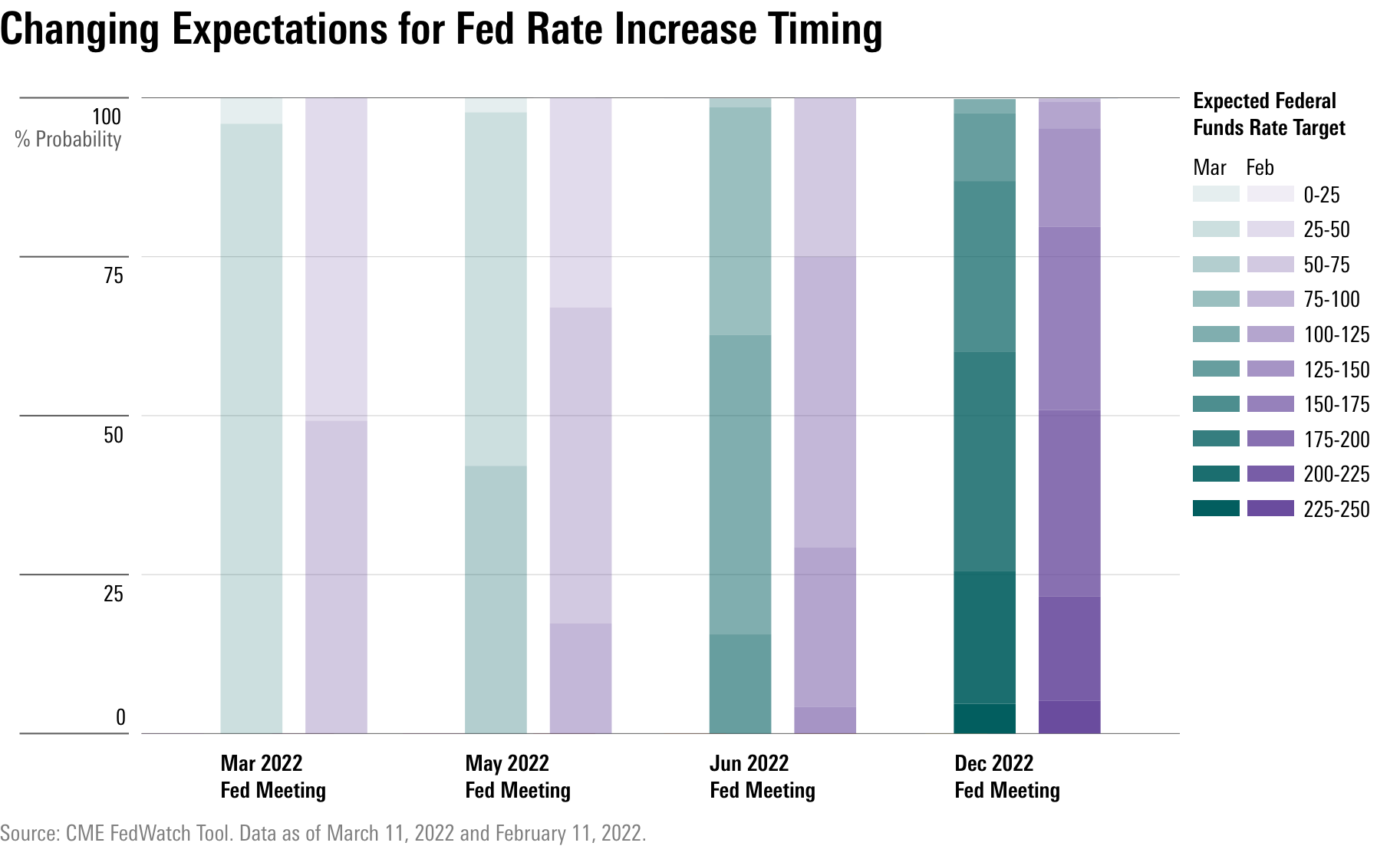

Rate Expectations

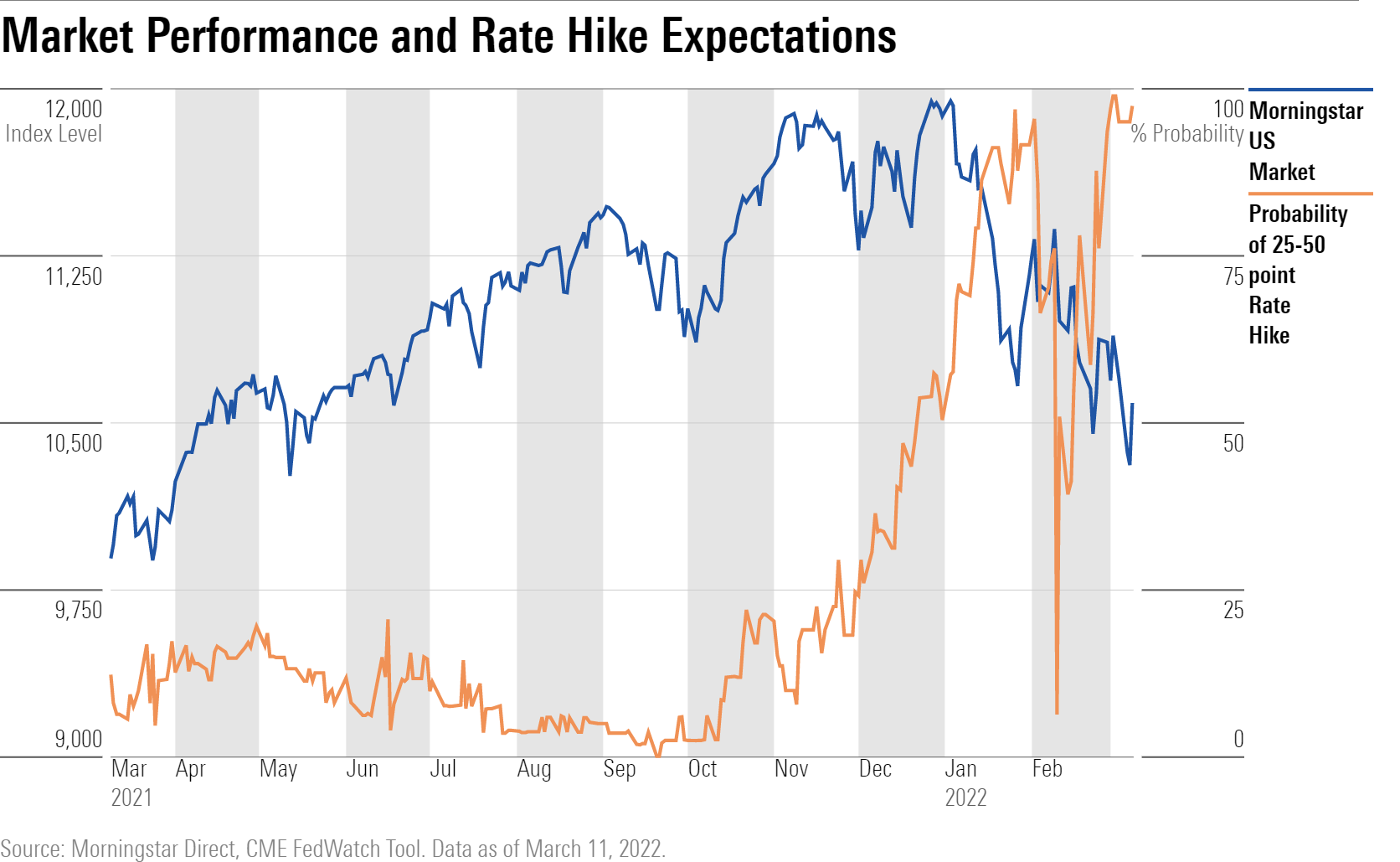

Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, uncertainty around the pace of Fed rate increases had perhaps been the most significant driver of volatility in the markets. Although inflation was pushing higher in the second half of 2021, prior to the start of this year, most investors expected a fairly relaxed pace of Fed rate increases that wouldn’t start until May or June.

But in January of this year, with inflation staying higher, longer, expectations began to accelerate and ramp up for the pace of Fed rate increases. Investors pulled forward the odds of a March liftoff, and as February began, the bond market began to price in a half-point increase this month.

Then came the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which led to a revision of expectations about the size and timing of what is anticipated to be steady quarter-point increases over the course of 2022.

Even though the Russian attack and subsequent sanctions against the country threaten to worsen inflation, they also could slow economic growth. In light of geopolitical developments, Fed chairman Jerome Powell said earlier this month he would support a 25-basis-point move when the Federal Open Market Committee meets March 15-16.

Powell said the Fed approach would be “careful” initially but could become more aggressive should inflationary pressures persist.

His unusually frank recommendation, made amid spiraling inflationary pressures and exacerbated by Russia’s Feb. 24 invasion of Ukraine, cemented market expectations for this week.

“The Fed has signaled pretty clearly that 25 basis points is the baseline,” says Eric Compton, equity strategist at Morningstar. “I’d be surprised if it deviated.”

For the stock market, the back and forth around expectations for the Fed were an important catalyst for the stock market’s swoon in January.

As expectations for rate increases grew, stocks--especially those for faster-growing companies trading at higher valuations--took a sharp hit. Growth stocks tend to get hit harder during inflationary times because a significant part of their allure is their future earnings profile, explains Morningstar’s chief U.S. market strategist, David Sekera. “As investors lower their growth expectations and discount those future earnings at a higher rate, the present value of the stocks falls further and faster than the broader market,” he says.

But at this point, the expectations for a quarter-point rate increase are so well entrenched, it would likely take a significant surprise for there to be a significant impact on the market.

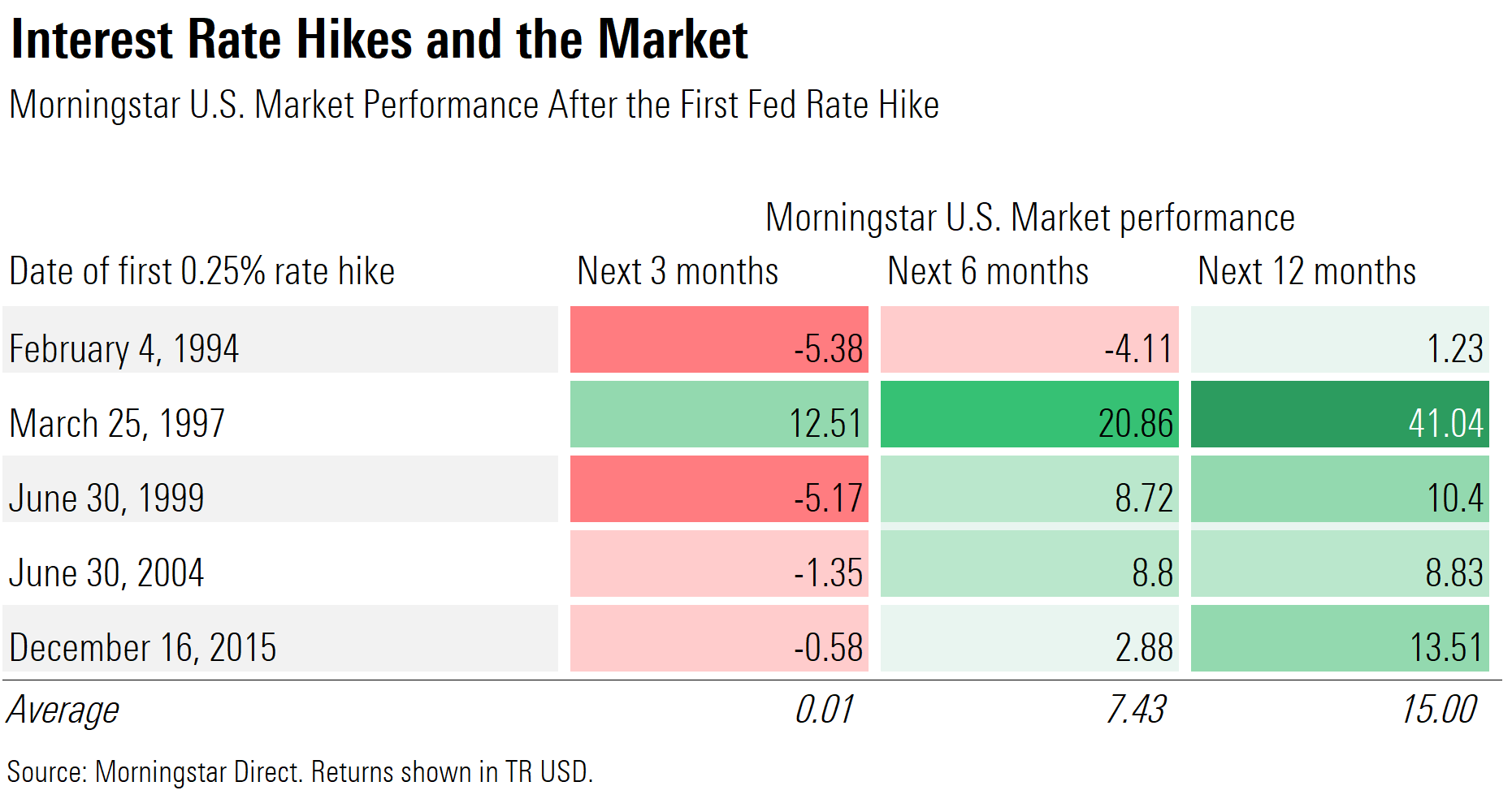

Stock Performance and First Rate Hikes

The Fed last began a rate-hike cycle in 2015 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. At that time, inflation was running under the Fed’s 2% target and the economy was strong. Now, policymakers are faced with a pace of inflation that well exceeds its target range combined with a tight labor market, consumer spending that continues to be robust, and the uncertainties presented by the Russia-Ukraine war.

In fact, since the Federal Reserve began tweaking its communication strategy in 1994 and more openly signaling its intentions, the market in most instances has tended to slightly underperform in the first three months following a rate hike and rebound strongly in the 12-month period.

Janet Yellen, a former Federal Reserve chair, may have helped set the stage for what the Fed will include in its commentary next week when she noted Thursday that the United States is “likely to see another year in which 12-month inflation numbers remain very uncomfortably high.”

Yellen’s remarks came following a report showing consumer prices are at their highest levels in 40 years. The Consumer Price Index, a measure of the cost of goods and services across the economy, rose to a 7.9% annual rate in February. Not since January 1982 when the CPI hit 8.4% has inflation been this high.

When it comes to monetary policy, the Fed is walking a tightrope of reining in inflation without slamming the brakes on the economy and causing a recession. Yet, long before the Ukraine invasion, inflation was running high and the market anticipated more aggressive action.

Compton adds: “The main concern is inflation. What’s happening in energy and agriculture won’t be easily controlled by the fed-funds rate. Everything else going on will be the driving force” of what happens in the market.

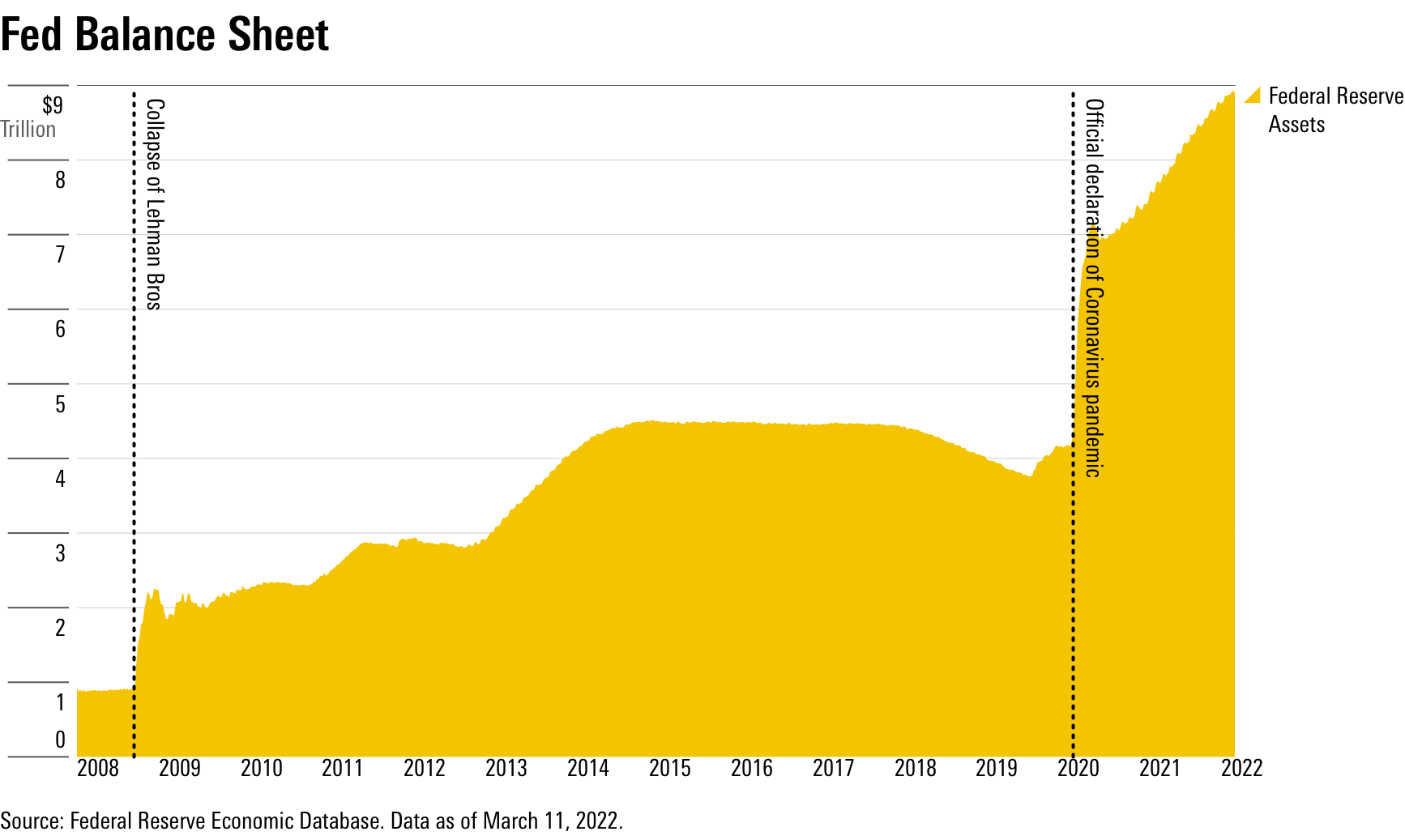

From QE to QT

More important, Compton says, is what the Fed says about its plans and targets for reducing the size of its balance sheet, which has ballooned to $9 trillion in assets, and the “tenor of the commentary” on current conditions. The Fed purchases--known as quantitative easing--are now expected to be followed by “quantitative tightening” beginning in May or June.

Market observers will be watching the pace of quantitative tightening closely. In many parts of the government-bond market, the Fed has effectively been the largest buyer of securities since early 2020; as it reduces its holdings, the potential is that bond prices could fall and yields go higher, which in turn could spill over into the stock market.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ba63f047-a5cf-49a2-aa38-61ba5ba0cc9e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/54RIEB5NTVG73FNGCTH6TGQMWU.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZYJVMA34ANHZZDT5KOPPUVFLPE.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MNPB4CP64NCNLA3MTELE3ISLRY.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ed88495a-f0ba-4a6a-9a05-52796711ffb1.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/ba63f047-a5cf-49a2-aa38-61ba5ba0cc9e.jpg)