A Sign of a Good Fund Company: It Doesn't Terminate Its Funds

The virtues of organizations that stand and wait.

The Early Bird

Morningstar was not the first researcher to appreciate the virtue of investment monotony, but it was the first to publicize that belief. In the early 1990s, my boss, Don Phillips, openly praised fund companies that dared to be dull. Firms that churned through their lineups, constantly launching and terminating funds, generated the headlines. But they were notably less successful.

The conspicuous example was American Funds, which in 1990 managed a modest 21 funds. Every one of those funds continues to operate today. Meanwhile, not only have most of its competitors' offerings disappeared, but so have those rivals themselves. Gone are Kemper, and Dean Witter, and Keystone, and PaineWebber, and Shearson Lehman Hutton … I mean Shearson Lehman Brothers … I mean Smith Barney Shearson. Speaking of which: Smith Barney is gone, too.

As Don himself will tell you, he whacked a slow-pitch softball. The above analysis benefits little from hindsight. Even at the time, the weakness of the whack-a-mole marketing strategy was obvious. (That said, most corporate executives failed to recognize the danger. There is sometimes an advantage to observing through a window.) The approach could only succeed for so long. Eventually, investors would realize which fund companies sold investments that did not last. They would switch to organizations that fulfilled their promises.

The Evidence

Three decades later, Morningstar has at long last collected the data to support the anecdotes. Published this week, the white paper "As the Fund World Turns--Fund Lineup Turnover Globally," by Gabriel Denis, Bridget Hughes, Maciej Kowara, and Matias Möttölä, exhaustively measures the fund industry's product-development practices. Specifically, it provides the rates at which providers: start new funds and shutter old ones. The sum of those numbers becomes, to use the authors' terms, the company's "fund lineup turnover ratio."

The paper outlines the differences among organizations, countries, and investment categories. For example, funds that invest in alternatives have notably high lineup turnover ratios. This tendency, regrettably, echoes the peripatetic habits of alternative-fund shareholders, who tend to chase recent performance. Similarly, actively run funds have higher ratios than do passive funds.

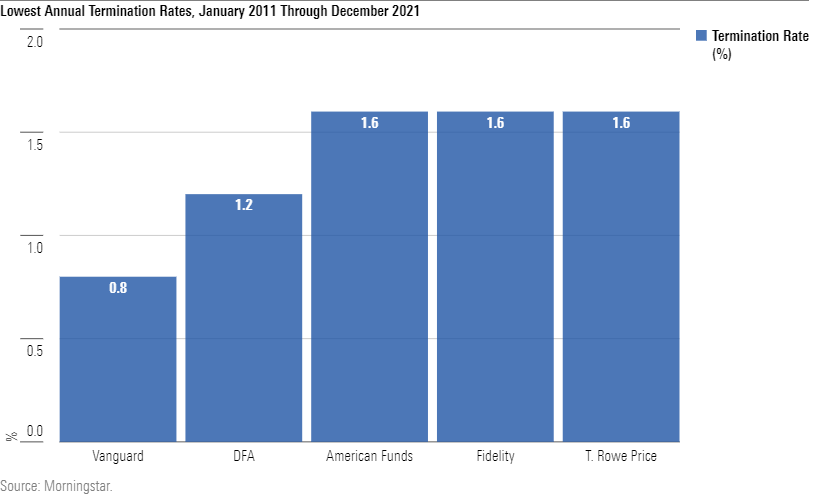

That's far too much material for me to cover. (Those who wish to learn more should turn either to the paper itself, or await a summary of its findings, which will be published next week on Morningstar.com.) My interest for this article consists solely of one column in the paper's Exhibit 12, which shows how frequently each of the major companies has folded its funds over the past decade.

The Patient Ones

I selected the death rate rather either the birth or overall rates because, while creating many new funds can be a sign of desperation, with marketers throwing new products against the wall to see what sticks, the effort can also be justifiable. That holds particularly true from a global perspective. Companies that expand into additional marketplaces often have no choice but to launch fresh funds.

Nor is a high termination rate always bad. In 1990, fund liquidations consistently signaled trouble because providers closed funds that they themselves had created. Garbage in, garbage out. However, most such businesses have since exited the industry. More recently, high shutdown rates have tended to come from firms rationalizing their lineups after acquisitions. There's nothing wrong with that.

The good news: While today's marketplace possesses no equivalent of Dean Witter (hurrah!), it does contain companies that behave at least somewhat in the spirit of American Funds, including (duh) American Funds itself. Several leading fund providers rarely liquidate their creations. That forbearance remains a sign of quality. Not all good organizations are abstemious, but those organizations that are abstemious are good.

The chart below lists the five fund companies with the lowest 10-year fund obsoletion rates, derived from a list of the 30 largest firms. The calculation includes all mutual funds and exchange-traded funds in Morningstar's global database. Despite the computation's international roots, its lessons also apply at home, as the companies run their American lineups in similar fashion.

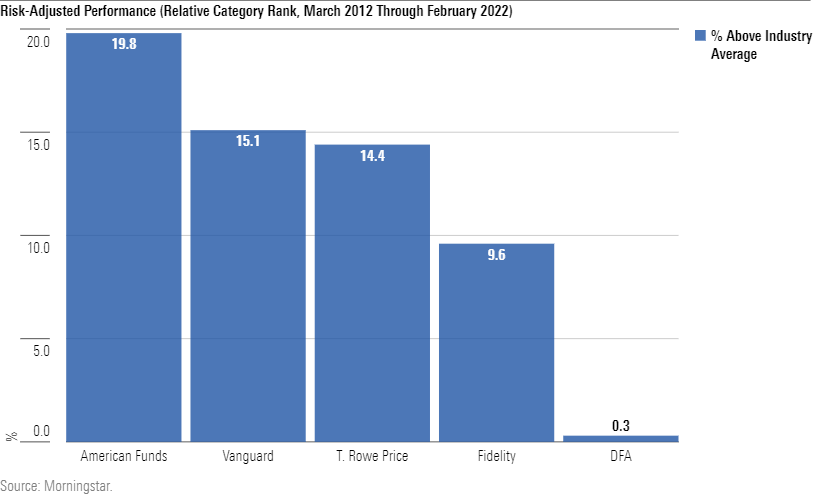

I then computed the performances for the U.S. funds from these slowpokes over the 10-year period from March 2012 through February 2022. The measure was the category ranking for Morningstar Risk-Adjusted Return, which evaluates how a fund fares against its peers. (Once again, these calculations include mutual funds and exchange-traded funds.)

As the average category ranking for all funds is not one's initial guess of 50, but instead the rather peculiar total of 45.7 (the reason why follows this article), I won't display those amounts. Instead, I will subtract the family's average category ranking from the industry standard. A positive outcome means that the family's average category ranking was that much above the norm, with a negative outcome indicating the opposite.

The Same as It Ever Was

The top finisher is familiar, eh? Thirty-two years later, the obvious choice from 1990 continues to excel. None of the other families should surprise, either. Were one to survey veteran financial advisors, asking them to name the five best fund companies, this would likely be their very list. (Well, at least among traditional mutual fund providers; the advisors might also mention ETF managers BlackRock BLK, Schwab SCHW, or State Street STT, which failed to make the obsolete-rate cut.)

In summary, although predicting individual fund performances is very difficult, forecasting the fortunes of fund companies is not. Organizations that stand by the funds that they offered, year after year, decade after decade, will do their shareholders proud. That claim was correct 32 years ago, when Don made it, and it will be correct for the next 32 years, as well.

Addendum

For those who enjoy being bored (which, in fairness, is this column's theme), here is why the mean for the category rankings is below 50. When Morningstar assigns percentile rankings, it does so by giving the top-ranking fund a score of 1. From there, it assigns percentiles by the formula 1/N, with N being the number of funds in a category. Thus, with a small category that contains only 5 funds, the rankings would be 1, 20, 40, 60, and 80, thereby making for a category average of 40.2.

Goofy, but all other percentile-assignment schemes also have quirks.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)