The System Still Fails Small 401(k) Plans

Workers at companies with small plans are burdened by high costs.

Busy Day

This week, my colleague Aron Szapiro hit the workplace trifecta. Morningstar launched the research site that Aron heads, Center for Retirement & Policy Studies, which contained a new white paper from Aron and Lia Mitchell, "Retirement Plan Landscape Report." In addition, Aron testified before a congressional subcommittee that reviewed retirement and mental health issues.

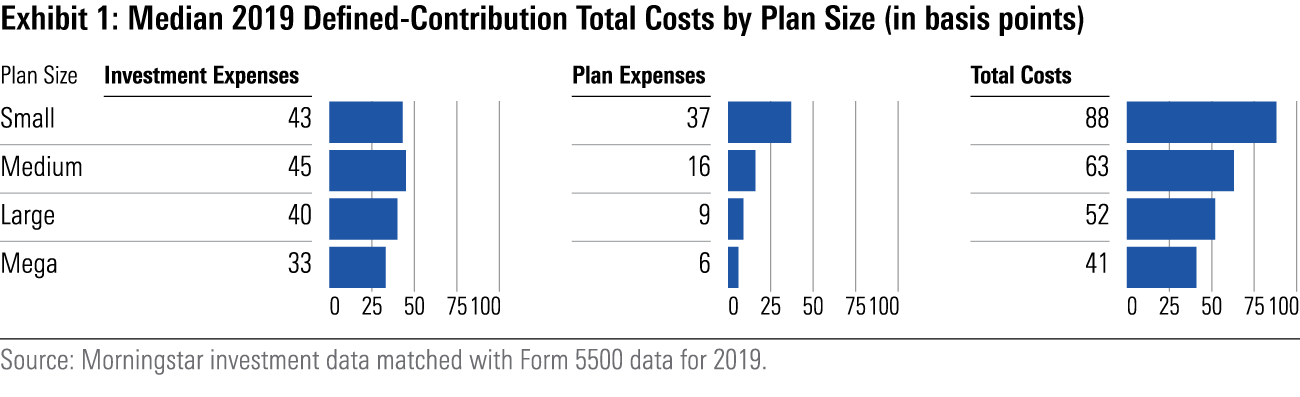

The most notable aspect of Aron's testimony, at least for me, was the divergence in costs between small and large 401(k) plans. This was already known. Anybody who has investigated the 401(k) system realizes that big organizations have the clout to demand and receive discounts from 401(k) providers, while smaller firms usually take what they are given. However, Aron's figures, recently gathered through an exhaustive study of Form 5500 filings, were striking.

Steep Overhead

In 2019, when the most recent data were available, there were 649,000 small 401(k) plans, which Morningstar defines as programs that hold $25 million or less in assets. (Which means that they aren't necessarily tiny, as a plan that contains 200 employees, each of whom owns a $100,000 account, would qualify as "small" by this definition.) Such plans hold 27% of the nation's 401(k) assets.

On average, small-plan participants pay slightly more than double the fees of those who invest through the largest companies. The main issue is not fund expenses. Gone are the days when most small 401(k) plans held costly investments. Their current problems come instead from their administrative fees, which are 6 times higher than those paid by the largest plans.

Let's be Jack Bogle. Assume that two employees hold funds that make an annualized 7%, before expenses. One investor works for a company that has a "mega" plan (that is, one worth more than $500 million) with average costs for its size, while the other is in a conventionally priced small plan. The net annualized returns for the two employees are therefore 6.59% and 6.12%, respectively. Over 40 years, one dollar invested in the mega plan grows to $11.84, while one dollar contributed to the small plan becomes $9.76. That makes for an 18% haircut.

Of course, this analysis exaggerates the effect, as the math applies only to the participants' early dollars. As the employees age, their contributions have ever-shorter time horizons, thus shrinking the performance disparity. The outlook for small-plan investors isn't as bad as the initial numbers suggest.

The Cost Lottery

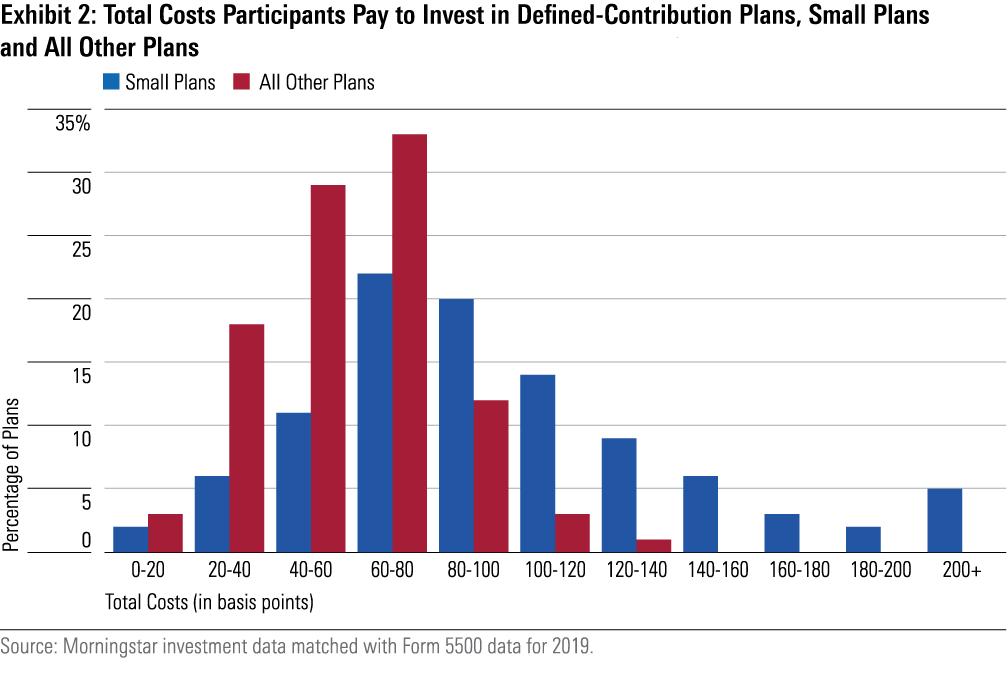

However, from another perspective, the news might well be worse. In addition to measuring average plan costs, Aron and Lia also calculated the distributions, to assess whether those means generally applied, or whether, as the cliché goes, the average temperature was comfortable because one hand rested in scalding water while the other was encased in ice. For small plans, it was very much the latter.

The following illustration shows the distribution of plan costs (that is, considering both fund expenses and administrative fees) for small plans in blue, and for all other plans in red. The red bars are clustered, with 75% of plans registering plan costs between 0.20% and 0.80% per year. The blue bars are, as they say, all over the map, including a broad splash to the right. Fifteen percent of all small plans are burdened with cripplingly high annual 401(k) expenses of greater than 1.40%.

Ever the optimist, Aron notes that an even higher percentage of small plans charge less than 60 basis points per year, which makes them fully competitive with other plans. This implies that attractive solutions do exist for small plans. Companies only need to find them. My response: That's all fine and good, but legislation that permitted 401(k) plans were legalized the year before my first date. The marketplace has had a long, long time to figure out how to adequately serve small plans, and overall, it continues to fail.

A Flawed Structure

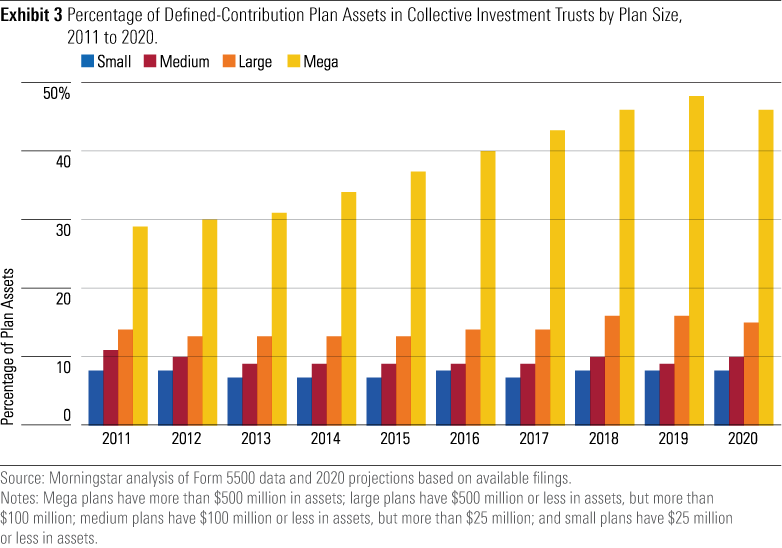

Another problem for small plans is that they have missed out on the leading trend among the giants: the switch to collective investment trusts, or CITs. Increasingly, mega 401(k) plans have swapped their mutual funds for cheaper CITs, which have grown over the past decade from less than 30% of such plans' assets to more than 40%. Meanwhile, the CIT market share among small 401(k) plans has remained unchanged, mired at less than 10%.

I once thought that with some modest legislative assistance, small-plan troubles could be resolved. My view has changed. The marketplace is fundamentally flawed. It thrusts small businesses into a role that they mostly play poorly, by forcing them to become investment and legal authorities in establishing 401(k) plans. As four decades of 401(k) experiences have demonstrated, that is asking too much.

Participants would be better served by a different 401(k) structure. Rather than force businesses to negotiate their own 401(k) terms, when most firms lack both the investment volume and expertise to accomplish the task, the system should recast them as facilitators. Upon joining a company, employees would be automatically enrolled into one of many available 401(k) plans that had been registered on a national platform. The relationship would then exist solely between the participant and 401(k) provider. The employer would have no further responsibilities.

(A few months ago, I wrote that the United States only needed a single 401(k) plan, rather than multiple choices. The argument had a certain rhetorical power, which is why I made it, but one need not take such a drastic step to fix the current problem.)

Such an approach would give companies of all sizes access to the same deeply discounted plans. (That said, if a giant organization wished to bypass the system by forming its own plan, it could so.) No longer would 401(k) plans separate American workers into two retirement-planning tiers. What's more, this proposal would preserve the best aspect of the current system: rivalry among providers, with each hoping to attract the most assets by offering the strongest plan.

It may be objected that my proposal would increase the government's role, as a federal agency would be required to oversee the plan registry. Quite the contrary. More than 200 lawsuits against companies that sponsor 401(k) plans now clog the nation's courts. Absolving businesses of their fiduciary duties would put an end to such actions. Who could object to that outcome save for the lawyers?

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BC7NL2STP5HBHOC7VRD3P64GTU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)