Why the 60/40 Portfolio Continues to Outlast Its Critics

The doubts keep coming, but so does the strategy.

Dead Again

These days, it's fashionable to bury the conventional investment strategy of investing 60% of a portfolio's assets in stocks and 40% in bonds. In September, CNBC published an article by an investment professional stating that the 60/40 portfolio had become obsolete. A month later Barron's wrote that the 60/40 approach "hasn't worked," before following up in November with a feature entitled "The 60/40 Portfolio Is Dead." This January, Kiplinger's concurred.

As the greatest 20th-century philosopher would have said, this is deja vu all over again. Because 10 years ago, similar claims abounded. In March 2009, an investment organization published "The Death of 60/40." Shortly thereafter, the era's most famous fund manager, Pimco's Bill Gross, also laid the strategy to rest. (The story has since been removed from The Wall Street Journal's site, but this message board discusses his argument.) Several other money managers agreed.

Looking Elsewhere

It’s understandable why 2009’s investors distrusted 60/40 portfolios. Although some U.S. equities had thrived, with energy stocks and REITs posting 10% annualized returns for the decade, the major stock-market indexes had lost money. Thanks to their bonds, most 60/40 portfolios had finished in the black--but only slightly. The real money was made elsewhere.

The “elsewhere” consisted of alternatives: hedge funds, real estate, and private equity. Although all three investments fell along with the stock market during the 2008 global financial crisis, the first two had sailed smoothly through the 2000-02 technology bust. As a result, funds that had branched out into alternatives had little trouble outgaining their more-traditional competitors.

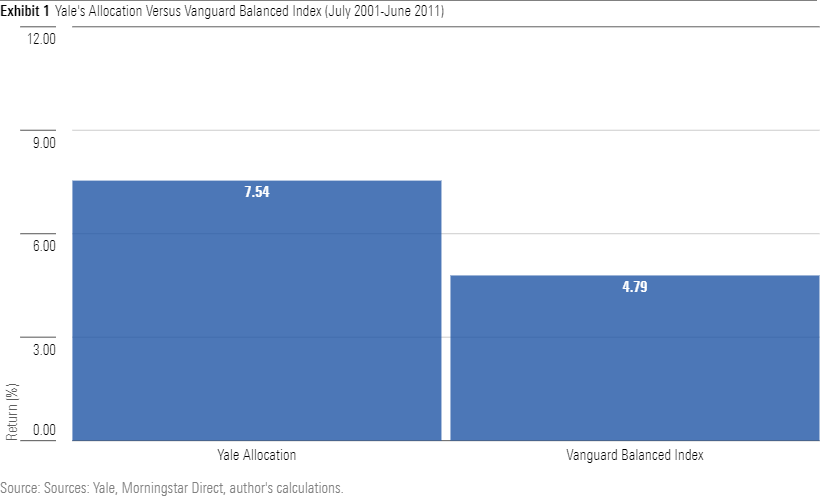

The following chart illustrates the point. It provides the annualized returns for 1) the asset allocation used by Yale’s endowment fund and 2) Vanguard Balanced Index VBINX, over the 10-year period from July 1, 2001, through June 30, 2011. (Yale’s fiscal year runs through June, not December.) With two thirds of its holdings in alternative securities, Yale’s fund epitomized the modern investment approach, while Vanguard Balanced Index followed the traditional path.

(For evaluating allocation results, comparing the Yale fund’s actual return against that of Vanguard Balanced Index would be misleading, because Yale manager David Swensen selected securities so astutely. Therefore, I have recalculated Yale’s performance by showing how the fund would have fared had it used the same allocation, but rather than buying individual securities, it owned indexes instead.)

The Following Decade

Vanguard Balanced Index hadn't been bad, as it had outpaced inflation during those years. However, the fund suffered much volatility along the way, including a 32.6% drawdown during the global financial crisis. That was a big loss for a strategy that delivered only a moderate payoff. Surely investors could improve their prospects by incorporating alternatives, most of which had outgained Vanguard's fund.

What’s more, fixed-income yields had shrunk, thereby lowering the expected returns for a 60/40 portfolio’s bonds. Fixed-income securities would continue to serve as ballast, offering at least some protection against stock-market swings, but their returns would be anemic. Nor would equities deliver outsize returns. Their valuations weren’t particularly compelling, especially as economists expected corporate earnings growth to be sluggish for the foreseeable future.

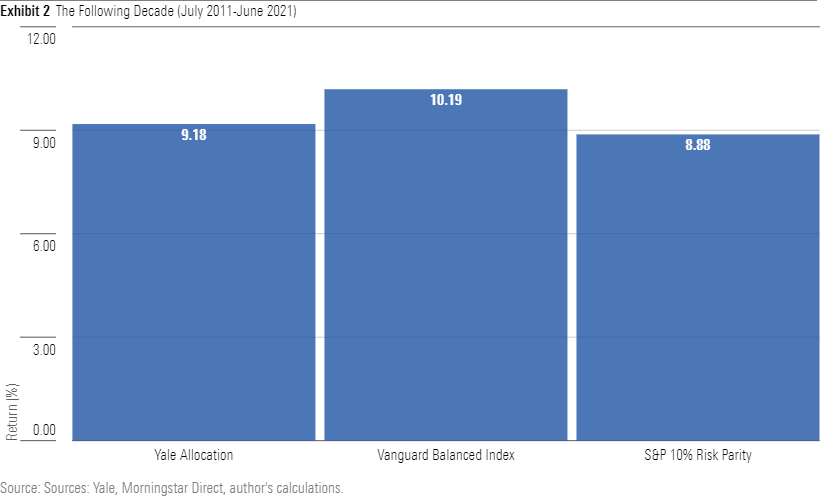

Or so the matter seemed in 2011. To widespread surprise, the 60/40 portfolio promptly blitzed the competition. It didn’t surpass Yale’s return over the ensuing decade, thanks to David Swensen’s continued (and unrivaled) ability to identify, in advance, top-performing investment managers, but this time around the 60/40 strategy outgained Yale. That's an impressive achievement given that Yale was heavily invested in risky private-equity and leveraged-buyout funds.

The 60/40 portfolio also comfortably led so-called "risk parity" strategies, another form of alternative investing that had become popular in 2008's wake. To make a long story short, risk parity funds de-emphasize equities in favor of other investment assets. The few risk parity funds that existed during the 2000s outperformed 60/40 portfolios. However, as evidenced by the returns of the S&P Risk Parity Index--10% Target Volatility, 60/40 portfolios then evened the score.

What’s Next?

To give contemporary 60/40 skeptics their due, they have broken with investment tradition by disparaging a recently successful strategy. That is a refreshing break from the norm. That said, the underlying logic of the 60/40 skeptics hasn’t much changed over the past decade. Once again, they distrust 60/40 portfolios because bond yields have become too low and equity price/earnings ratios too high.

Perhaps so, but as the past decade has shown, it's certainly possible that bond yields will decline further and equity valuations will continue to increase. Also, who is to say that the substitutes for a 60/40 portfolio will be an improvement? After all, alternative investments consist either of equities in a different wrapper (as with private-equity funds, venture-capital funds, or leveraged-buyout funds), or of real assets, many of which are also aggressively valued. For example, the price of gold bullion has risen 50% over the past three years, and, despite vacancies caused by the coronavirus pandemic, the price of U.S. commercial real estate has soared.

In the second Barron's article, five investment advisors were asked how they would alter the 60/40 formula, given today's conditions. Each recommended selling bonds. Two would replace those bonds with publicly traded equities, while the other three would do so with a mix of alternative equities and real estate. In other words, all five would make the 60/40 portfolio riskier to compensate for the fact that bonds can no longer be expected to offer an adequate return.

My own counsel (were I to offer such a thing) would take the opposite course. Avoid the temptation to become more aggressive when investment opportunities seem scarce. Instead, maintain the same 60% equity position but consider reducing the portfolio’s bond-market risk by swapping into shorter notes or even raising cash. If long Treasury yields continue to rise, as they have done since summer 2020, those monies can gradually be reinvested into longer-dated securities.

But that is merely a gentle suggestion, and a temporary one at that. More generally, I do not challenge the wisdom of the 60/40 portfolio. Ten years from now, I will likely be writing a follow-up column demonstrating how the strategy remains valid.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/MFL6LHZXFVFYFOAVQBMECBG6RM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HCVXKY35QNVZ4AHAWI2N4JWONA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EGA35LGTJFBVTDK3OCMQCHW7XQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)