Should You Buy Commodity Producer ETFs?

Direct commodity ETFs are a more attractive way to get exposure.

A version of this article previously appeared in the November 2021 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Download a complimentary copy of Morningstar ETFInvestor by visiting the website.

Commodities exchange-traded funds tend to offer investors exposure to a variety of commodities via one of two avenues: 1) by purchasing commodity futures contracts and regularly rolling them over, or 2) directly buying and storing the commodity, which is only feasible for precious metals.

But investors can also back into second-hand commodity exposure by owning shares in commodity producers. ETFs that zero in on commodity producers weave portfolios of companies whose operations are generally aimed at extracting specific commodities. For example, Van Eck Gold Miners ETF GDX and Global X Silver Miners ETF SIL feature firms that mine gold and silver, respectively. The spot prices of these precious metals directly affect the stock prices of the firms that dig them out of the ground. While these funds don’t purchase commodities or commodities futures, Exhibit 1 illustrates that their performance has been closely correlated to the prices of the precious metals they produce.

Commodity producer ETFs rarely offer the same diversification benefits as those that invest in commodity futures or physical precious metals, however, and they may not deliver the experience investors expect. For investors looking to add a dose of commodity exposure to their portfolio, a more-direct bet is the best approach.

Low Production Value

Many investors introduce commodities to their portfolio to reduce risk. Gold, in particular, tends to attract investment because its ebbs and flows generally do not correspond to the stock market’s currents. Over the 10 years through December 2021, SPDR Gold Shares ETF GLD--a physically backed fund that buys and stores gold--had a beta (a measure of market sensitivity) of 0.19 relative to the Morningstar Global Markets Index.

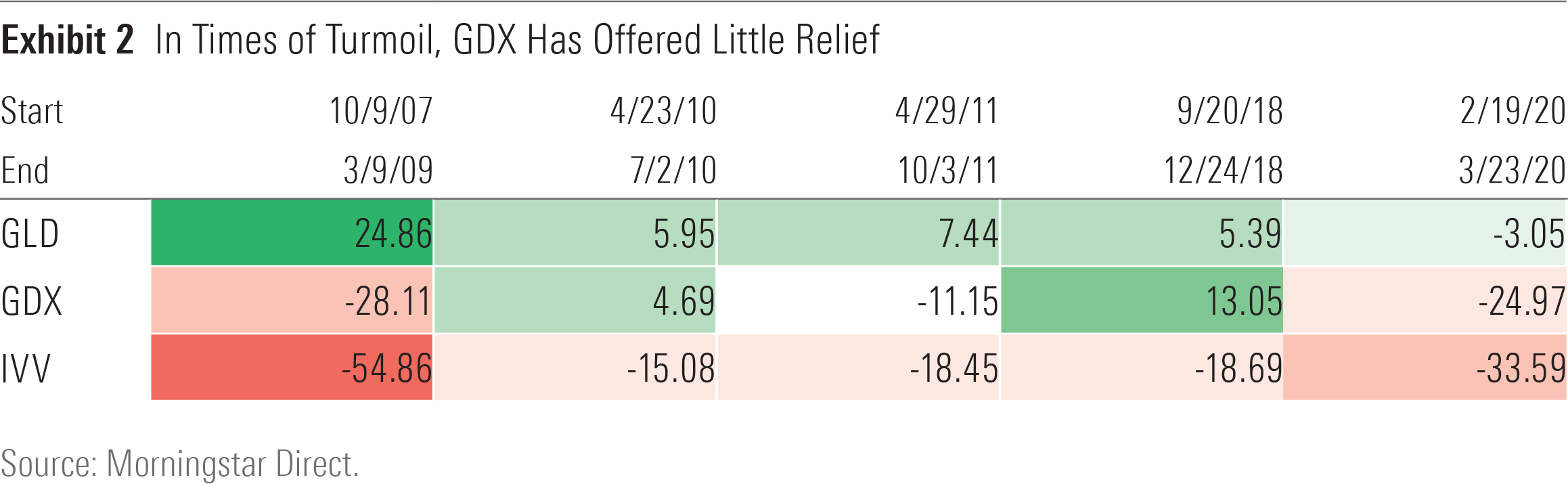

Producer ETFs--funds that invest in mining companies, in this case--have not reliably delivered the same benefits. The stocks that shape these portfolios tend to move with commodity prices, but they are not immune to the direction of the market. Exhibit 2 compares the performances of GDX and GLD over stretches in which the S&P 500 slid more than 15% since the funds’ common inception. Gold mining stocks have proved to be more “stock” than “gold” in these instances, providing investors with little relief from the market’s turmoil.

Exhibit 2 looks like it contradicts Exhibit 1, which shows that GDX tends to perform similarly to its physically backed counterpart, GLD. GDX’s divergences from the spot price of gold have indeed been infrequent, but they’ve also been poorly timed. Exhibit 3 illustrates that GDX’s market beta leapt at the onset of the coronavirus-driven market drawdown, mimicking the broad market at the worst moment it could. GLD, on the other hand, stood pat. The fire sale in early 2020 was unique--even historically-stable-in-the-face-of-a-market-meltdown silver took a dive--but it showed that producer ETFs don’t have the same risk-reduction power as true commodities funds.

Even during smoother markets, precious metal producer ETFs tend to offer bumpier rides than direct commodity funds. Over the 10 years through December 2021, GDX was more than twice as volatile as GLD, as measured by its standard deviation of returns. The spot price of gold is the sole driver of GLD’s movements. On the other hand, the operating and financial leverage layered onto GDX’s holdings amplifies these spot price movements. While this can improve performance when gold prices climb, it comes with downside risk that many investors may find unpalatable.

Physically backed ETFs do incur storage costs, but they’re immaterial. This cost is theoretically passed on to investors via fund expense ratios, but precious metals commodity ETFs generally charge lower fees than miner ETFs. GLD levies a 0.41% expense ratio, while GDX takes a 0.50% toll. SLV is 15 basis points cheaper than SIL.

Past Precious Metals

Producer ETFs can look more attractive for commodities that cannot be stored, like oil and agricultural products. A ton of soybeans requires far more real estate than a ton of silver, so these commodities ETFs turn to the futures market, getting exposure with futures contracts.

This approach comes with headaches. When the commodity futures curve in question is in contango--a state where longer-dated contracts sell for more than the current one--these funds mechanically buy high and sell low as each contract expires. Their performance can differ materially from the commodities’ spot prices as a result. Producer ETFs need not worry about these pitfalls because they invest in stocks rather than forward contracts.

While commodity producer ETFs may make more sense for long-term investors when the alternatives must own futures to get exposure, several drawbacks limit their appeal.

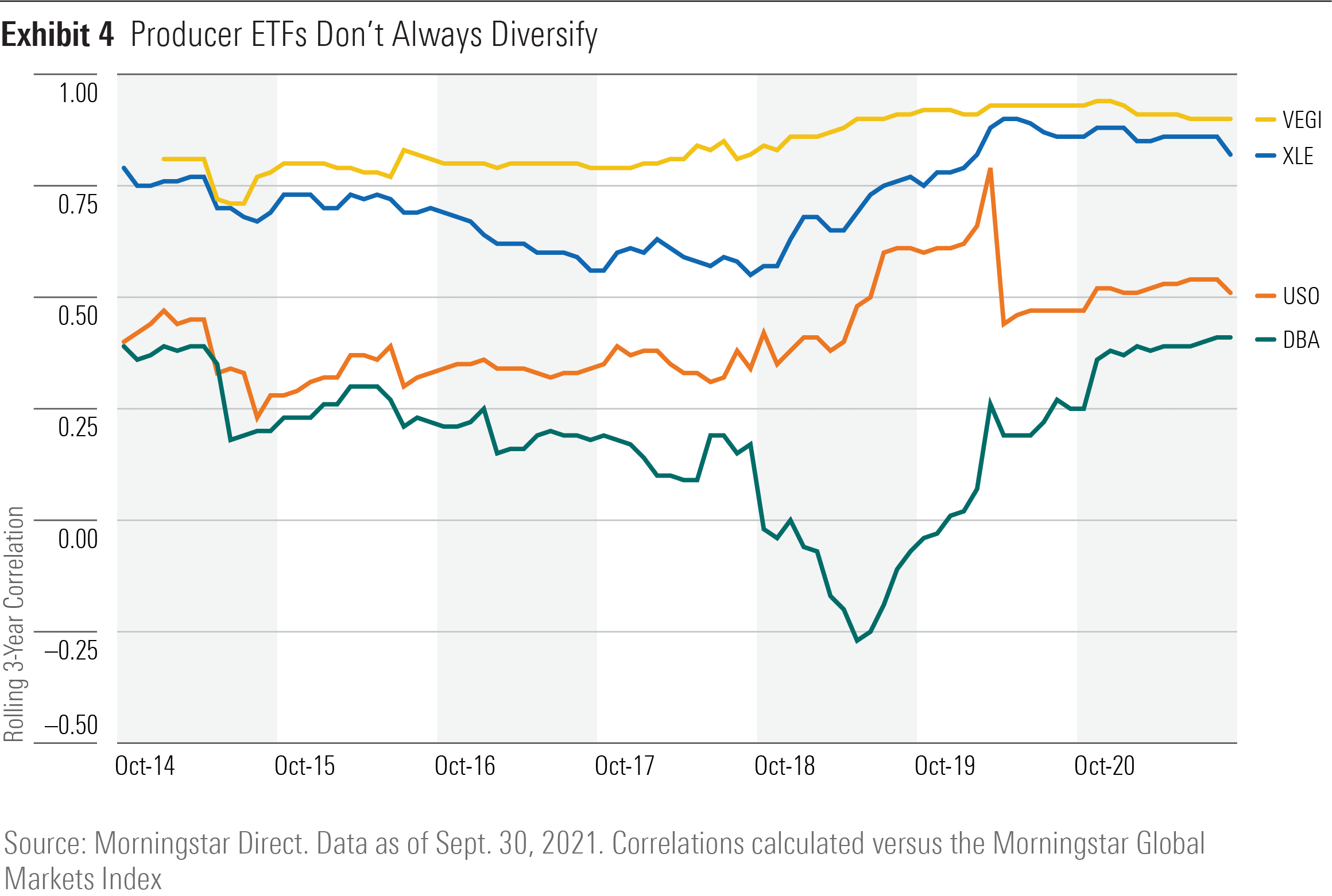

For one, like precious metal miner ETFs, energy and agricultural commodity producer ETFs do not offer the same level of diversification as their direct counterparts. Exhibit 4 shows that Energy Select Sector SPDR ETF XLE, a market-cap-weighted portfolio of the S&P 500’s energy names, has more closely mimicked the broad market than United States Oil USO, which gets oil exposure via futures and other derivatives. The disparity is even more pronounced between iShares MSCI Global Agricultural Producers ETF VEGI and its futures-focused counterpart, Invesco DB Agriculture DBA.

Additionally, energy and agricultural commodity producer ETFs may not even deliver the commodity exposure that investors expect. This is rarely a concern for miner ETFs. While some firms in GDX or SIL have operations in addition to mining, it’s clear how they are exposed to the intended commodity.

Producer ETFs outside of the precious metals space cannot always say the same. For example, VEGI allocated nearly 20% of its portfolio to Deere & Co. DE as of Jan. 21, 2022. One can connect Deere tractor sales to the spot prices of various crops, but the relationship is far from ironclad. Deere’s returns have been more closely correlated with the Morningstar Global Markets Index than DBA over the past three years. In fact, that is the case for stocks representing over 87% of VEGI’s portfolio as of end-December.

The stocks that shape energy producer ETF portfolios are more clearly tied to energy prices. Exxon Mobil XOM and Chevron CVX--two of the world’s largest oil producers--jointly represented more than 40 % of XLE at the end of December 2021. Still, even the performance of these oil behemoths has correlated more closely with the stock market than the price of oil over the past three years. Investors must understand that while producer ETFs offer a path to avoid the futures market, the exposures they provide are more stocklike than commoditylike.

An Outdated Approach

Investors have historically used producer stocks for commodities exposure because the avenues for direct exposure were expensive and complex. Commodities ETFs offer a simplified solution. While those that invest in futures face challenges of their own, direct commodity ETFs are a more attractive mechanism for commodities exposure than producer ETFs.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Morningstar, Inc. does not market, sell, or make any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/30e2fda6-bf21-4e54-9e50-831a2bcccd80.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/30e2fda6-bf21-4e54-9e50-831a2bcccd80.jpg)