What to Know About Capital Gains Distributions

Why they matter for taxable accounts.

Holiday Gifts

The United States is indeed exceptional. In almost every other developed country, funds are treated like stocks. Shareholders pay taxes on their income, but they are not docked for capital gains until they redeem their funds. Not so in the U.S. Each year, mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, and closed-end funds must distribute the net capital gains they realize from their portfolio trades.

These distributions typically occur in November and December. Most funds have Oct. 31 fiscal years, after which they calculate their required distributions, then announce and pay those sums before the calendar year’s end. On occasion, such payments are huge. For example, Harbor Disruptive Innovation HIMGX has proved true to its middle name, announcing that on Dec. 22 it will make a capital gains distribution equal to 44% of its current net asset value.

That's painful news for those who own Harbor Disruptive Innovation in a taxable account. Their tax bills will be considerable. If, for example, a Harbor Disruptive Innovation shareholder is subject to the maximum capital gains tax rate of 23.8% (the 20% base rate plus a 3.8% Medicare surtax), that investor will owe the IRS 10.5 cents for every fund dollar. That amount exceeds the fund's 2021 year-to-date total return. One step forward, two steps back.

An Initial Response

A rejoinder to this complaint is that, like the Grim Reaper, the IRS always receives its due. So, why worry about capital gains distributions? After all, when funds make distributions, they lower their net asset values by that amount, thereby reducing the capital gain (or increasing the capital loss) when shareholders redeem their shares. Investors can pay more in taxes today, with a fund that makes frequent distributions, or they can pay more tomorrow. It all works out.

That claim is technically correct. (That said, it does not apply to those who bequeath their funds to others, or who have a lower capital gains tax rate when selling the fund than when they purchased it. There are several reasons to dislike capital gains distributions. This column, however, will confine itself to the situation where the investor retains the fund and her tax rate does not change.)

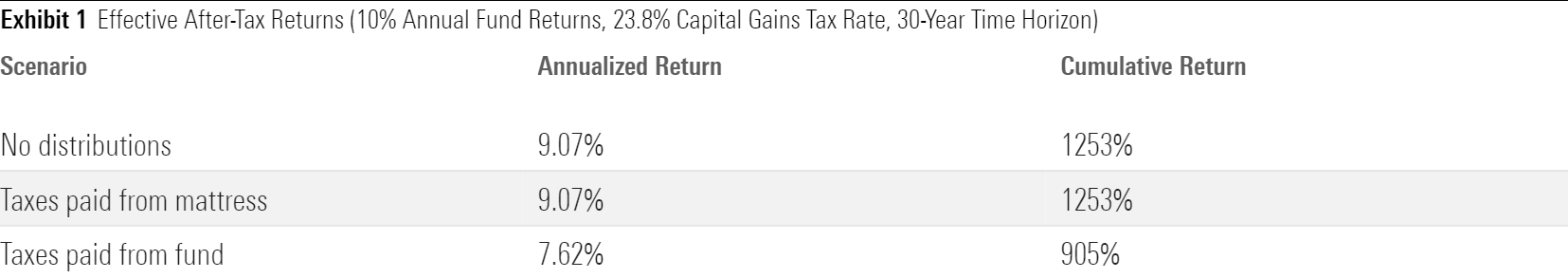

Place $100,000 into a fund that makes a steady 10% per year (Bernie Madoff lives!), without ever making a distribution, and that investment will be worth $1.74 million in 30 years. After feeding the IRS when the fund is sold, the shareholder will retain $1.35 million, which makes for an after-tax return of an annualized 9.07%.

Conversely, our investor could have bought the nation’s most tax-inefficient fund, which also appreciates at 10% annually but distributes all its profits in the form of capital gains distributions. If the investor reinvests those distributions into the fund, while paying taxes from cash that that is stored in her mattress, her after-tax proceeds at year 30 will once again be $1.74 million. Along the way, she will have spent $391,000 from her mattress on capital gains tax bills, leaving net proceeds of $1.35 million. The same total dollars, the same 9.07% rate of return.

In Reality

This example explains why people sometimes say that fund distributions don't matter. However, the calculation contains within it a false premise: that the monies used to pay the taxes came from a virtual mattress. Those dollars were invested in something. And, because they were remitted to the IRS, rather than remaining in that investment, they forfeited future profits. Implicitly, the claim that distributions in taxable accounts are immaterial rejects the time value of money.

How, then, should one model the problem? The simplest method is to assume that the taxes were paid directly from the fund's distribution. That is, with a 10% distribution and 23.8% tax rate, the fund's one-year return would be lowered by 2.38 percentage points, to 7.62%. This is the approach taken by all after-tax calculations of which I am aware, including the SEC's and Morningstar's. It is conservative but also unrealistic. Few investors pay their capital gains taxes from their fund assets. Typically, they withdraw monies from another account.

If the naive approach understates the cost to taxable accounts of capital gains distributions, and the official approach overstates the problem, is there a happy medium? Not really. Determining the true cost of paying taxes up front cannot be done without knowing where those monies would have otherwise been stashed. Obviously, that decision varies by investor.

Nonetheless, we have at least outlined the range of possibilities. The exhibit below depicts the three scenarios. The first row portrays the effective tax-adjusted performance of the fund that makes no distributions; the second row shows the result for the fund that distributes everything, assuming that the investor pays taxes from monies that would otherwise not have earned a return; and the third row depicts what happens if the taxes for the high-distribution fund are paid from the fund itself, as with the SEC/Morningstar calculations.

Wrapping Up

The difference is large indeed! Admittedly, this example is extreme. Last decade, the largest actively run U.S. stock funds distributed an average of 4% of their assets as capital gains, rather than 10%. Nonetheless, the concern is legitimate. Over time, the opportunity cost of paying the IRS earlier rather than later is substantial, assuming that the investor does so with assets that would otherwise have been profitably employed.

Next Tuesday, Morningstar’s Amy Arnott will follow up this rather theoretical column with a more practical one. She will outline how investors can identify funds that are likely to make larger-than-average capital gains payments. Such funds need not be avoided, but they are best used within tax-sheltered accounts.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PLMEDIM3Z5AF7FI5MVLOQXYPMM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/I53I52PGOBAHLOFRMZXFRK5HDA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/CEWZOFDBCVCIPJZDCUJLTQLFXA.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)