Asset Allocation When You Have Enough

What you’d like to achieve with any “extra” assets can help you calibrate your portfolio’s equity exposure.

This article was previously published on Nov. 8, 2021.

I recently chatted with a retired couple who were looking for a second opinion about their portfolio’s asset allocation. They were fortunate enough to amass a sizable portfolio through diligent saving, a frugal lifestyle, and inheritances from some family members who passed away. Because the inherited assets included numerous individual stocks, their total equity weighting is on the aggressive side—about 65% of the portfolio’s assets.

They also shared that they feel they have more than enough money for any foreseeable living expenses, even after carving out a substantial portion of each year’s spending for charitable donations and ongoing monetary gifts to their children. The key question: Is 65% in stocks too high for someone in their situation? In this article, I’ll walk through some ideas about how to think through these issues. (I've changed all dollar amounts and other identifying details for privacy purposes.)

First, Cover the Basics

For people in retirement, it’s always helpful to start by looking at spending from the bottom up. Jot down what your spending looks like in a typical month, including costs for housing, food, medical care, insurance, clothing, charitable donations, and taxes. (Our budget work sheet can help with this.) That gives you baseline for estimating annual expenses. Then you can add in discretionary spending, such as travel, entertainment, major purchases, and the like.

If you’re working with a financial advisor, he or she should be able to use this data to estimate your lifetime spending needs and stress-test how long your portfolio might last in different scenarios. If you’re managing your own assets, you can do a rough calculation by reverse-engineering the 4% rule, a guideline that suggests retirees set a dollar value for annual withdrawals equivalent to 4% of the starting portfolio value and adjust the withdrawal amount each year for inflation. (To be on the conservative side, you could reduce the number to about 3.5% in case future market returns are lower than they’ve been in the recent past.) To find the size of the portfolio you’ll need, multiply your planned annual spending by the inverse of the withdrawal percentage; for example, someone who plans to spend $50,000 per year would need a portfolio of at least $1.4 million ($50,000 times 28.6, which is the inverse of 3.5%). That amount should be sustainable over a period of up to 30 years, so it builds in an extra cushion for investors who might have a shorter time horizon.

It’s also prudent to build in some additional assets for unforeseen expenses, such as long-term care. Costs vary significantly, but someone who needs several years of assisted living, home care, and/or nursing home care might spend as much as $300,000 or more later in life. Depending on how conservative you want to be, you could also build in additional assets in case you want to decide to increase discretionary spending at some point in the future. In our hypothetical scenario, investors might conclude they want to set aside at least $2 million for their core retirement portfolio.

One Size Doesn’t Fit All

Next, it’s time to think about asset allocation for these core assets. For a retiree with a 20-year time horizon and a moderate level of risk tolerance, a 50% equity allocation could be considered reasonable. (Depending on the retiree’s risk tolerance, the level of equity exposure for the core portfolio could be as low as 40% or as high as 60%).

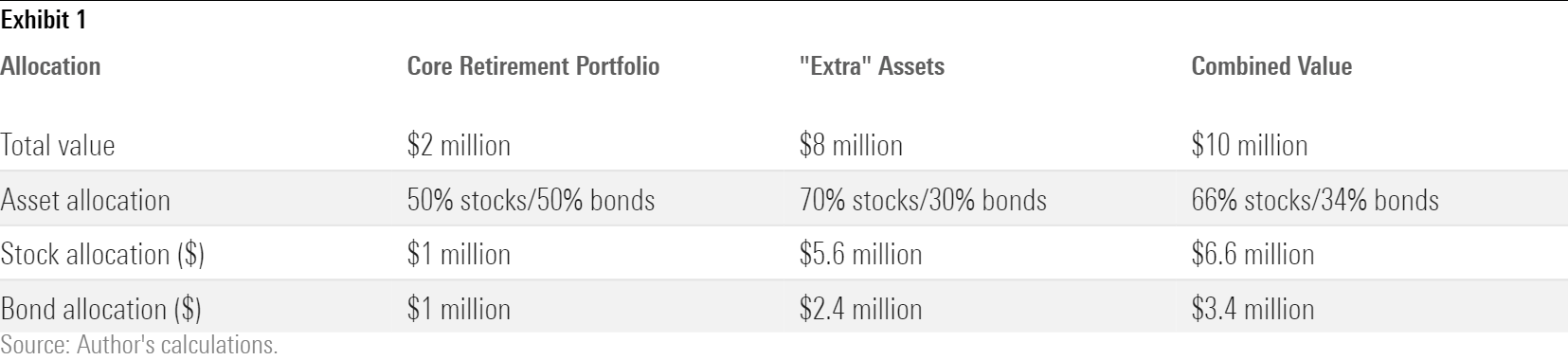

Scenario 1: Legacy Focus

If you don’t anticipate needing to draw down assets outside of the core retirement portfolio, it can be helpful to think of the additional assets as a separate “bucket” for asset-allocation purposes. How to allocate these assets depends mainly on your individual goals. If you want to prioritize leaving assets (bequests) to charity or family members, you might be comfortable with a higher equity allocation, which should allow for continued growth while the assets are still in your portfolio. The table below illustrates what this might look like.

With a higher equity allocation for the “extra” assets, the combined portfolio ends up with an asset mix of about 66% stocks and 34% bonds. (Coincidentally, that’s pretty much in line with the asset mix that prompted the question).

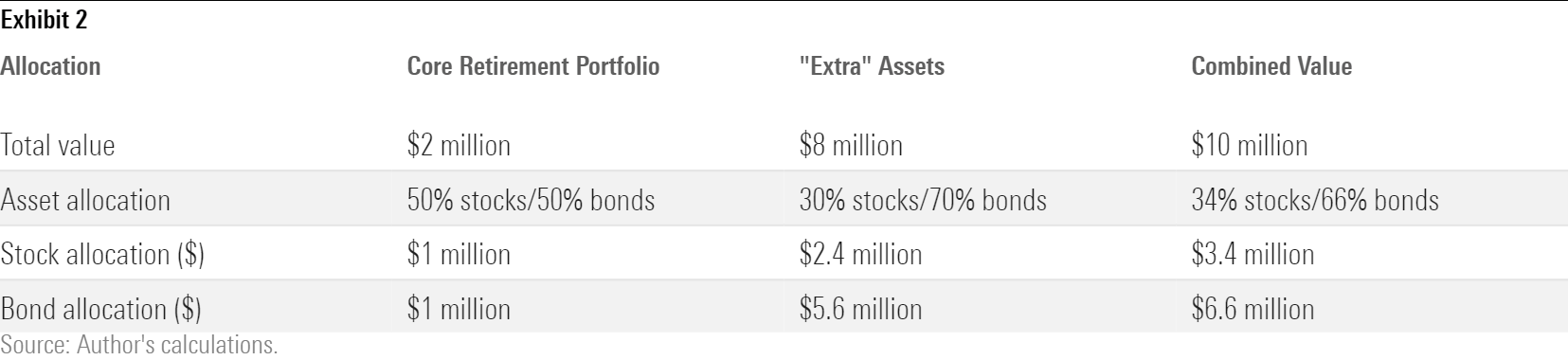

Scenario 2: Capital Preservation Focus

Investors who aren’t as focused on asset growth for eventual bequests to charity or family members might be more comfortable prioritizing safety instead. Tilting the “extra” portfolio toward bonds provides more of a buffer against market downturns and should lead to a more stable portfolio value from year to year. As Christine Benz discussed in a previous column, there’s no need to take on additional risk if you’ve already saved enough to meet your financial goals. As shown below, the combined portfolio would end up with a significantly more conservative asset mix, which could provide more peace of mind for investors who value safety and aren’t worried about asset growth.

Of course, the two scenarios illustrated above are just a starting point. A couple in this situation might end up deciding on a portfolio allocation somewhere in between, or decide to carve out additional buckets, such as a separate bucket for charitable donations during their lifetime or another bucket for “fun money” to enjoy the fruits of a lifetime of work and saving.

Other Considerations

Even for investors comfortable with a higher equity allocation, it’s prudent to reduce exposure to individual stocks if they’re significantly overvalued or consume a large percentage of the portfolio (5% or more is a rough guideline). That might mean paying taxes on realized capital gains, but donating appreciated assets to charity is a way to avoid that issue.

It’s also worth considering whether each spouse has the same level of risk tolerance and comfort with investing. In the past, it was common for one spouse (typically male) to take primary responsibility for personal finance and investment issues while the other spouse (typically female) was less involved. Fortunately, that situation is rapidly changing as more women take steps to empower themselves and learn about finance and investing. Still, it’s worth thinking about how a surviving spouse might handle remaining assets and make sure the portfolio’s asset mix is something both members of the couple are comfortable with for the long term.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, there’s no “right” answer to creating an asset-allocation mix. It all comes down to an individual’s level of risk tolerance, portfolio size, and anticipated spending needs. But investors who have enough assets to cover their planned spending during retirement—and then some—have more flexibility to create a customized asset mix that reflects their goals and priorities.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)