Are You Behind on Saving for Retirement?

There’s a path forward, no matter when you start your retirement-plan contributions.

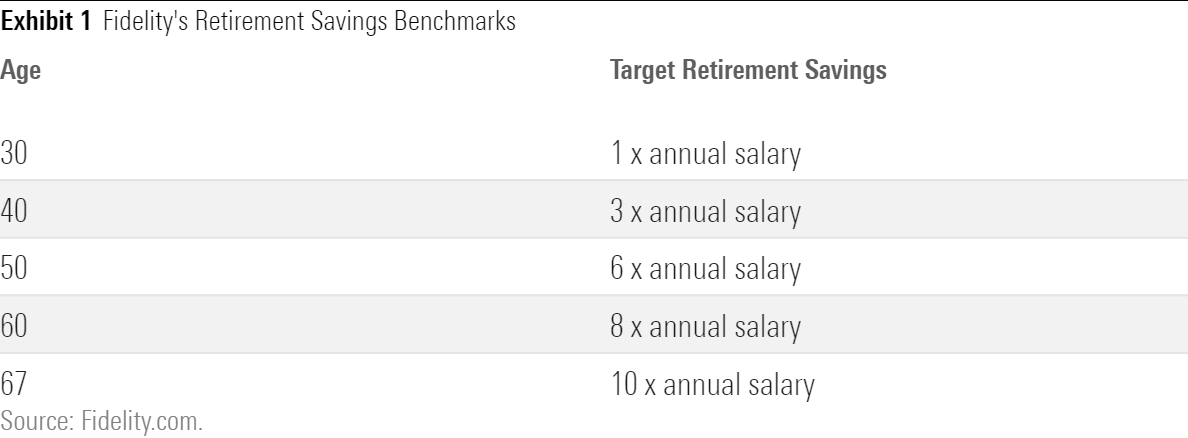

Back in August, I wrote a piece focusing on Fidelity’s age-based retirement savings targets, which involve targeting a dollar amount equal to a certain multiple of salary at different ages. I ran a simple year-by-year test to see how the numbers might play out in practice based on the assumptions Fidelity used, which were 1.5% real wage growth per year, a savings rate equal to 15% of salary, retirement at age 67, and an income replacement target of 45% of pre-retirement income. I also assumed that retirement-plan contributions started at age 25 and continued consistently until retirement.

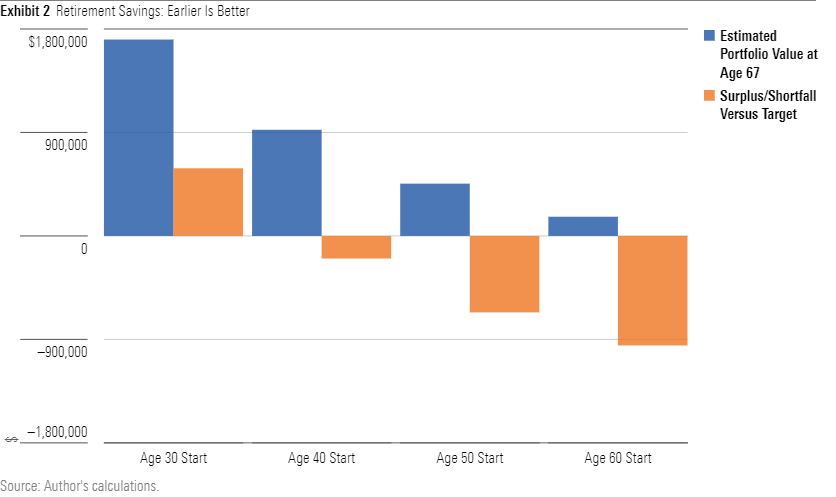

Not surprisingly, a hypothetical investor who followed these guidelines should be in decent shape for retirement savings, barring any major portfolio mishaps or unusually bad market returns. But what about those who get a later start? In this article, I’ll take a closer look at whether it’s possible to catch up at various ages and suggest some concrete steps for closing the gap. The good news: If you don’t start saving for retirement until your 30s or 40s, catching up should be well within reach. But even investors who didn’t start seriously saving for retirement until age 50 or later can still make decent progress toward shoring up retirement assets.

The Numbers on Retirement Saving by Age

To see how investors might fare if they don’t start saving for retirement until later in their careers, I used the same assumptions from Fidelity’s study but adjusted the starting dates. I used a starting salary of $65,000 per year at age 30 for the salary-based benchmarks. Instead of backing into a required rate of return, I assumed investors earned annual real returns in line with long-term historical averages. I also assumed that investors kept their portfolios diversified between stocks and bonds, with portfolio allocations roughly in line with the typical target-date fund that would match their planned retirement dates.

As a caveat, it's worth noting that some investors who are behind on saving for retirement might lack the income security or other resources needed to start saving, which can persist over multiple decades. Each of the scenarios below assumes that investors who start saving at a given age are able to consistently funnel 15% of their annual income toward retirement, which may not be feasible for everyone. Even investors who sign up for their employers' retirement plans early in their careers often contribute lower percentages over time. As a general guideline, though, the projections below illustrate the benefits of starting early and suggest some other steps individuals can take if they're running behind.

Note: Projections assume retirement savings of 15% of salary starting at the given age, a $65,000 starting salary at age 30 with 1.5% annual wage growth, a portfolio mix that becomes more conservative over time, and market returns in line with long-term averages.

Starting Date: Age 30 This is probably the most realistic scenario for many retirement savers. Young employees in their 20s are often just getting started in their careers and may need to funnel most of their earnings toward other financial priorities, such as paying off student loans or meeting basic living expenses.

That’s not the end of the world, though. A retirement saver who starts consistently saving 15% of his or her income at age 30 should be able to catch up relatively quickly. Assuming portfolio returns in line with historical averages, such a person should be able to catch up to Fidelity’s savings targets (which target retirement savings equivalent to 3 times salary by age 40) by about age 42. Every year counts, so the earlier you can start saving for retirement, the better.

Starting Date: Age 40 Things start getting a bit more difficult here. A person who began contributing to retirement savings at age 40 might not fully catch up, even after consistently carving out 15% of each year's salary for retirement over the next 27 years. If her portfolio generated returns in line with historical market averages, she would end up about $200,000 shy of Fidelity's age-based target of $1.1 million (which is equivalent to 10 times an assumed salary of $112,760 at age 67).

There are three main ways investors could catch up: boosting retirement savings to about 18% of salary, maxing out retirement plan contributions each year starting at age 40, and/or taking advantage of “catch-up” retirement contributions starting at age 50, which would boost total retirement savings to $26,000 per year. Based on my projections, each of the three tactics would help push the portfolio’s ending value over the target level by age 67. Of the three strategies, maxing out retirement plan contributions starting at age 40 would lead to the largest portfolio value at retirement, even without the additional benefit of catch-up contributions starting at age 50.

Starting Date: Age 50 This situation actually isn't all that uncommon. Retirement savings might not be top of mind when retirement is decades away, and many people find that basic living expenses (such as food, clothing, shelter, child care, transportation, and insurance) soak up the majority of their income during the early to middle stages of their careers. In addition, some individuals might be just getting restarted in their careers after taking time off to raise a family during their 30s and 40s.

Unfortunately, it’s tough to catch up at this age by using retirement-plan savings alone. Saving 15% of salary starting at age 50 would leave the portfolio well short of target levels by age 67. I estimated a portfolio value of roughly $450,000 at age 67, compared with the age-based target of $1.1 million. And even taking full advantage of catch-up retirement contributions by consistently saving $26,000 per year from age 50 through age 67 would still leave the portfolio about $300,000 short of the target. That means investors who don’t get started with retirement savings until midlife will probably need to supplement their retirement savings by making contributions to taxable accounts.

Starting Date: Age 60 Investors who don't start saving for retirement until age 60 might feel some regret for not starting sooner. And it's true that even a diligent savings program--taking full advantage of catch-up retirement contributions by consistently saving $26,000 per year from age 60 to 67--would still lead to an estimated portfolio value of only $270,000, well short of the $1.1 million target.

As with the previous age group, though, older investors can help close the gap by contributing aggressively to taxable accounts in addition to maxing out retirement-plan contributions. But investors who start saving only a few years before retirement will probably need to take additional steps, such as cutting back on planned retirement spending, delaying retirement for a few years or working part time during retirement, downsizing to a smaller home to free up more cash, or purchasing an immediate or deferred fixed annuity to help fill the retirement income gap.

What It All Means for Retirement Savings

Saving for retirement can be a daunting task, and feelings of guilt over not getting started earlier can make it even more dispiriting. But it's important to keep in mind that no matter how late you start, there's almost always something you can do to improve your prospects for retirement. As the inspirational saying goes, start where you are, use what you have, and do what you can. Even small steps in the right direction can help improve the outcome.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)