What the Best Index Funds Have in Common

When it comes to doing your homework on index funds, understanding index construction is indispensable.

A version of this article previously appeared in the September 2021 issue of Morningstar ETFInvestor. Click here to download a complimentary copy.

Index methodologies are index funds’ DNA. They are the instructions that dictate how indexes—and by extension index funds—select and weight their constituents. They impose constraints. They put in parameters for regular upkeep. Index methodologies define the makeup of an index fund’s portfolio, its return potential, and its risk.

Understanding index construction is central to index fund due diligence. Here, I’ll discuss its place in Morningstar’s ratings process, share a template for decoding index funds’ DNA, and list some of the traits of the best indexes.

Suss the Process

The Morningstar Analyst Rating is a forward-looking, qualitative rating. Our analysts do deep due diligence on a wide array of investment strategies (active, passive, and all things in between) and a variety of investment vehicles (mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, separately managed accounts, and more) to assess which ones we believe to be investment-worthy and which we think investors should avoid. In assigning these ratings, we explicitly score the people, parent firm, and process behind each strategy.

When we rate index funds, process is paramount. Our Process Pillar ratings receive an 80% weight in calculating our overall rating for index funds. Why? Because our assessment of index funds’ processes centers around their index methodologies—their DNA. While we favor experienced, well-resourced index portfolio management teams (our People Pillar rating gets a 10% weight in our overall rating for index funds) and parent firms that align their interests with those of their investors (our Parent Pillar rating gets a 10% weight), nurture tends to take a back seat to nature when it comes to index portfolios.

If we’re primarily concerned with index construction when assigning Analyst Ratings to index funds, how do we go about putting benchmarks through their paces?

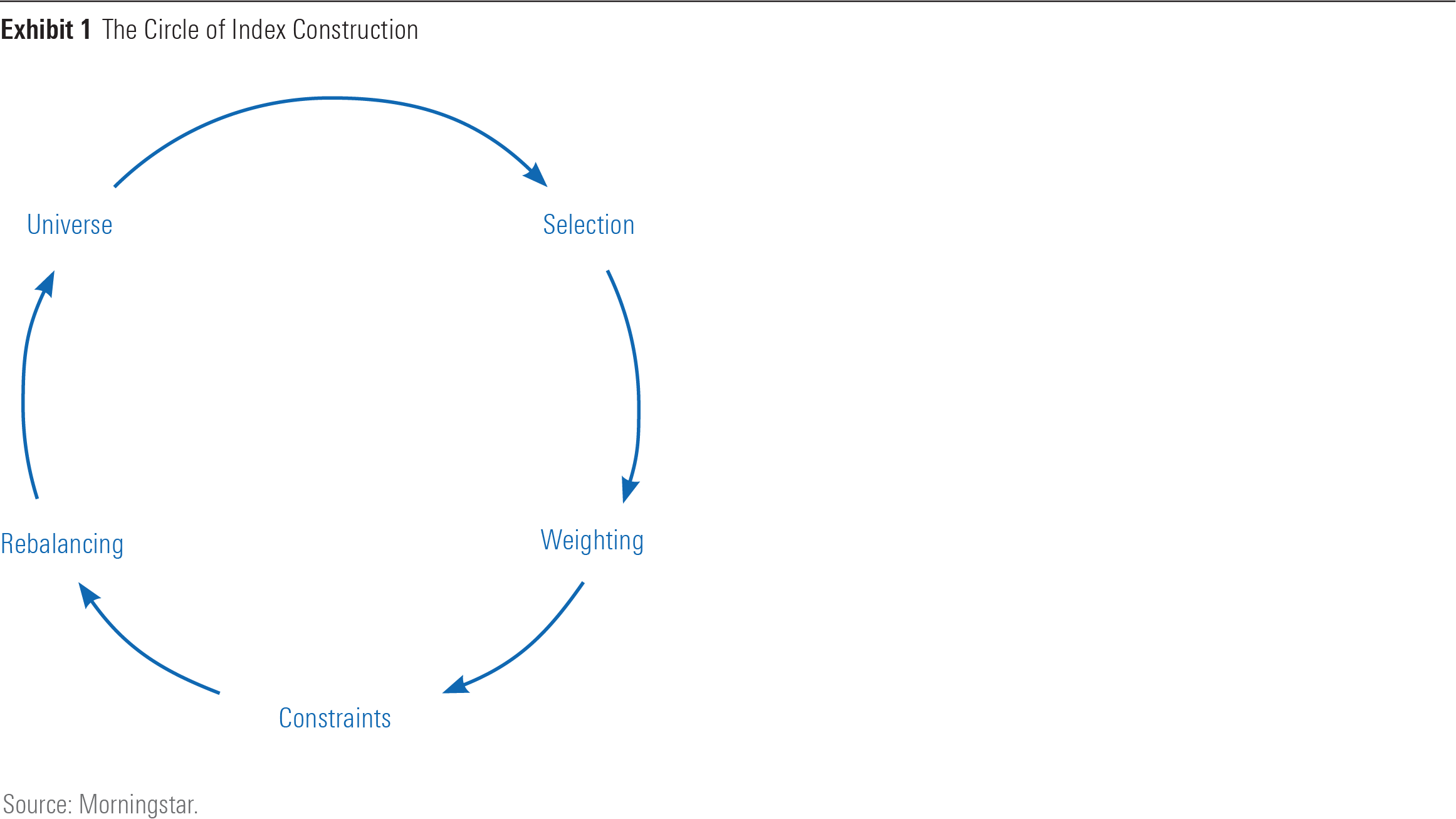

The Circle of Index Construction

Exhibit 1 is a diagram of what I’ll call the circle of index construction. It is important to remember that indexes are living things. They measure the markets but are affected by the markets just as much, and they’re always evolving. The circle is meant to evoke this vitality.

Universe. All indexes draw from a specific universe of eligible constituents. The scope of these selection universes ranges from the entire investable market capitalization of U.S.-listed stocks to green bonds to commodities futures contracts to cryptocurrencies and beyond. An index's universe represents its investment opportunity set—its palette. A broader and more-diverse palette allows an index to better represent its opportunity set and gives it more potential directions to set out on. A narrower universe equals a less vibrant palette. Global stocks represent a broad universe, Malaysian micro-caps a tiny one. The breadth, depth, and diversity of indexes' selection universes have important implications for the makeup of their portfolios.

Selection. The next stop on our trip around the circle of index construction pertains to how an index selects its constituents from its selection universe. Just how picky is the index? Broad-based, market-cap-weighted indexes are minimally selective. They'll often weed out tiny, thinly traded securities that would be costly to include in the index's portfolio. As a result, these benchmarks wind up sweeping in virtually everything available to them in their universe. Other indexes are far choosier. Take the Dow Jones U.S. Dividend 100 Index, for example. The index underpins Schwab U.S. Dividend Equity ETF SCHD. It draws just 100 stocks from a selection universe of more than 2,600. In whittling the field, it kicks out REITs, boots stocks that haven't paid dividends for at least 10 years in a row, and more. It is crucial to understand the criteria that indexes use to decide what's in and what's out of their portfolios.

Weighting. Once index constituents are chosen, they need to be assigned a weight in the portfolio. There are many ways these weights may be allocated. Weighting stocks and bonds on the basis of their going market value has long been the standard. But the variety of approaches has multiplied over time. Index constituents may be weighted equally, according to their fundamentals, by their exposure to a particular factor or theme, and many, many other ways. Position weights will have a big influence on indexes' return potential and risk. Those that make bigger bets on a small handful of positions will likely be riskier than those that spread them more evenly. There's no guarantee that a high level of concentration will yield good results. The only given with a concentrated index is that it will look much different from its selection universe. And decoupling constituents' weights from their market value will almost certainly increase turnover.

Constraints. Indexes will often put constraints in place to limit concentration, tether themselves to the index that represents their selection universe, control for unwanted factor exposures, and more. These constraints can be simple, such as a 5% cap on the weight of any individual constituent. They can also be complex, like an optimizer that controls for a range of variables from sector exposures to factor exposures. Knowing what constraints an index has in place and why they are there can help us understand their impact on the portfolio.

Rebalancing. Indexes need to be refreshed regularly. Markets change, and indexes adapt to these changes through the process of rebalancing. The need to rebalance could be driven by corporate actions. New initial public offerings might have to be added to stock indexes, assuming they are eligible. Newly issued bonds may need to be included in fixed-income benchmarks. Other changes might be more frequent and of greater magnitude. Equal-weighted indexes regularly rebalance their constituents' share of the benchmark's value. Momentum indexes are regularly playing catch-up as they're always looking to target the market's recent top performers.

Rebalancing can play a critical role in the performance of some indexes, most notably factor-focused benchmarks. A timely rebalance can provide a lift to performance. For example, Invesco FTSE RAFI U.S. 1000 ETF PRF rebalanced into the teeth of the March 2009 market nadir. Doubling down on fundamentally cheap stocks just when they were desperately cheap gave PRF a shot in the arm. Conversely, bad timing can hurt performance. This was a lesson iShares MSCI USA Momentum Factor ETF MTUM learned coming out of its May 2021 rebalance. The fund rebalanced into the market’s recent winners, which happened to feature many value stocks that had come roaring back following favorable news about coronavirus vaccines in late 2020. MTUM added these stocks just as their comeback was running out of steam, and performance faltered as a result. Rebalance timing luck can result in opportunity costs.[1] And lucky or not, rebalancing always results in transaction costs. It is important to know how indexes manage their regular rebalances and the measures they have in place to mitigate these costs.

The Traits of the Best Indexes

Now that we’ve taken a whirl around the circle of index construction, let’s talk about the traits that typify a good index. These features are common to most of our highest-rated ETFs and index mutual funds, which earn some of our top Process Pillar ratings on account of their benchmarks’ sensible construction.

Representative. The best indexes are representative of the investment opportunity set or the style that they are trying to capture. Vanguard Total Stock Market ETF VTI carries a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Gold, chiefly driven by its High Process Pillar rating. It earns our highest rating on account of the degree to which its index, the CRSP U.S. Total Market Index, represents the investment opportunity set available to its peers. The benchmark captures nearly 100% of the investable market cap of the U.S. stock market. Few indexes are more representative than that. Casting a wide net and weighting by market cap puts the fund in a position to let its low fee shine through and give it a lasting edge versus category competitors.

Diversified. Diversification is the only free lunch in investing. In the case of index funds with zero fees, and those like VTI and others that effectively earn back their fees through a combination of securities lending and portfolio management savvy, investors will find the closest thing there is to a free lunch in the realm of investing. Diversifying broadly also reduces the likelihood of errors of omission. Over the long haul, a small minority of stocks account for the bulk of the market's returns. More-inclusive indexes have greater odds of owning the market's big winners.

Investable. Investability isn't an issue for most broad stock and bond benchmarks, but it becomes one in smaller, less-liquid segments of the market like micro-cap stocks and bank loans. Index portfolio managers may have a tough time tracking benchmarks in these corners of the market. Trading can be costly, which makes index-tracking tough. The best indexes cover parts of the market that are easy to invest in, and they take additional measures to ensure investability.

Transparent. I can't think of many examples of things inside or outside the realm of investing where complexity and opacity have proved superior to simplicity and transparency. The best indexes are simple and transparent. If you crack open an index methodology document and it reads like the pilot's manual to a Klingon warship, that's a red flag.

Sensible. Does the index methodology make sense? Weighting stocks by their share price might have made sense in 1896, when the Dow Jones Industrial Average was created. This approach made it easier for its publishers to calculate the index's value. But in 2021, does weighting stocks by their share price still make sense? Today we carry around more computing power in our pockets than existed on the planet at the turn of the 20th century. We have the ability to calculate benchmarks with sensible approaches to selecting and weighting securities in real time.

Turnover-Conscious. Turnover has explicit (commissions, bid-ask spreads) and implicit (market impact) costs. The best indexes are conscious of these costs and take steps to keep them under wraps. For example, in 2018 CRSP's U.S. equity indexes transitioned from rebalancing on one day to spreading rebalancing over a five-day period. This was done in an effort to minimize market impact. Other indexes take measures to either slow the rate of turnover or similarly spread it out over a longer period of time—to the benefit of index fund investors.

Good Genes

When it comes to doing your homework on index funds, understanding index construction is indispensable. Knowing the progressions around the circle of index construction and seeking out the traits of a quality index at each stop will put you in a position to pick best-of-breed funds for your portfolio.

[1] Hoffstein, C., Faber, N., & Braun, S. 2020. "Rebalance Timing Luck: The (Dumb) Luck of Smart Beta" https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3673910

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Morningstar, Inc. does not market, sell, or make any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/a90ba90e-1da2-48a4-98bf-a476620dbff0.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-22-2024/t_ffc6e675543a4913a5312be02f5c571a_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/PKH6NPHLCRBR5DT2RWCY2VOCEQ.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/54RIEB5NTVG73FNGCTH6TGQMWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/a90ba90e-1da2-48a4-98bf-a476620dbff0.jpg)