What Bad Returns at the Wrong Time Can Mean for College

The order in which returns unfold over time can either help or hurt.

A version of this article originally appeared on Oct. 5, 2020.

I’ve written a couple of articles about how sequence-of-returns risk can affect portfolio values both for retirees making portfolio withdrawals and younger investors who are putting money away for the future. The order in which returns unfold over time is important because it can affect the dollar value of a portfolio that has cash flows from contributions or withdrawals. In a nutshell, the periods when more dollars are invested will carry more weight in your overall results.

In this article, I'll explain how even a year or two of bad equity market returns can affect portfolio values for college savers and will give some practical tips for dealing with this risk. I'll focus mainly on 529 plans, which we've covered extensively as one of the best vehicles available for families planning ahead to cover the costs of college education.

Background

The sequence of returns typically comes up in the context of investing for retirement. A negative sequence of returns during the first few years of retirement can be detrimental because it is a double whammy: It cuts into the portfolio's value right away but can also put long-term sustainability at risk because, as retirees make withdrawals, there's less money left to benefit from an eventual market recovery.

The situation is a bit different for parents or other relatives planning ahead for a child's college education because both savings and withdrawals are made over a shorter period. While younger investors can invest for retirement over a period of four decades or more, parents usually only have about 18 years to put money away for college. And withdrawals made to pay for college costs typically take place over about four years, compared with a much longer (but ultimately unknown) time horizon for retirees.

Because of this compressed time horizon, the main risk for college savers isn't technically the sequence of returns, but really the risk of an equity market downturn that happens shortly before planned withdrawals start. It is also worth noting that investors can sidestep this risk by using age-based investment options that automatically ratchet down their equity exposure based on the child’s age. Surprisingly, though, age-based and target-enrollment portfolios account for less than 40% of all 529 plan assets, with the remainder invested in static allocation portfolios.

As with saving for retirement, negative equity market returns are less of an issue early on. If you're just starting to invest in a 529 plan or other college savings vehicle for a newborn or young child, a year or two of negative returns won’t dramatically affect your long-term results. But as the portfolio value increases, the risk of too much equity exposure becomes more dangerous. This makes the last few years before your child starts college critically important. In a worst-case scenario, a market downturn later in high school--right in the middle of the usual swirl of activity with college visits, standardized tests, and last-minute applications--could depress the portfolio’s value right before you’ll need to start making tuition payments.

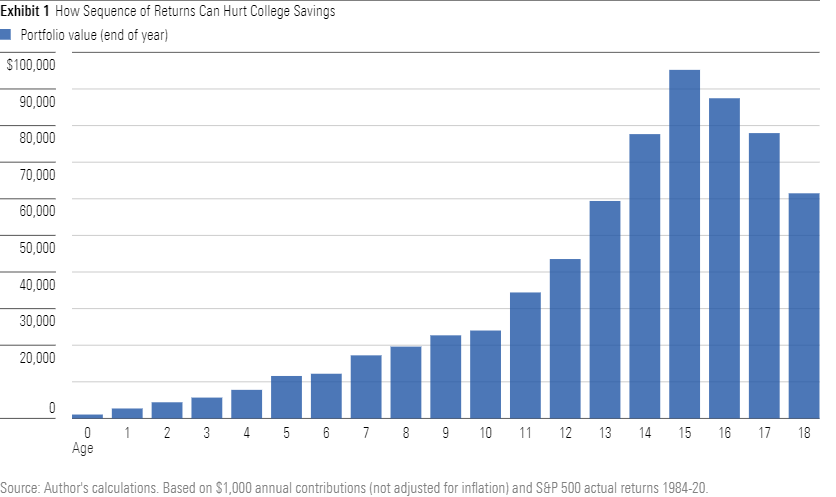

Let’s look at a couple of examples to see how this can play out in practice. For illustration purposes, I used an all-equity portfolio and assumed that parents or other college savers contributed $1,000 per year from a child’s birth up through age 18. That’s on the low end given recent costs for tuition, room, and board, but the same patterns would apply with larger contribution amounts. The table below shows portfolio values for a child born in 1984 assuming consistent annual contributions and actual equity market performance through 2002.

Up until age 15, this was a pretty positive period for market performance. The portfolio kept chugging along with positive total returns almost every single year, suffering only a small loss in 1990. Assets would have peaked (reaching more than $95,000) around the child’s freshman year of high school. But with the tech correction starting in 2000, things started to go south. After three straight years of market losses, the portfolio would have shed more than a third of its value by the end of 2002.

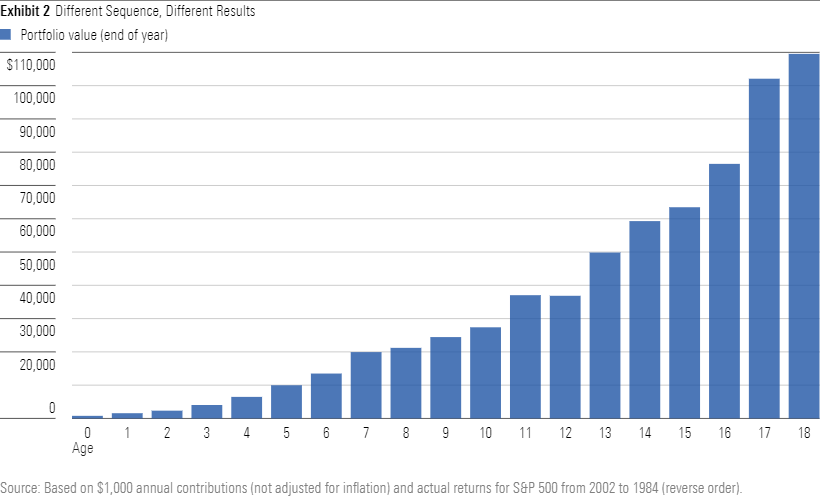

If the sequence of returns had been reversed, the picture would be far brighter. The chart below shows the portfolio’s value over a hypothetical period during which the equity market earned the same returns as it did from 1984 through 2002 but in reverse order.

Despite a rough start with three straight years of negative returns, the portfolio’s value would reach more than $109,000 by the end of the period--about $48,000 higher than in the previous example. That would give the family far more flexibility; they could opt for a more expensive college, carry over some assets to cover the cost of graduate school, or transfer assets to a younger sibling or other family member. (This is one attractive aspect of 529 plans; account owners can change the plan's beneficiary as long as the new assignee is a family member of the previous one.)

Mitigating the Risk

Of course, these are extreme examples; maintaining an all-equity college fund throughout your child’s entire childhood isn’t prudent or advisable. And in fact, adding a healthy stake in fixed-income securities is one of the best ways to offset the potential risk of equity market losses. Although bonds can also be subject to risk from return patterns over time, returns typically fall in a smaller range and can help buffer some of the risk of an equity market downturn.

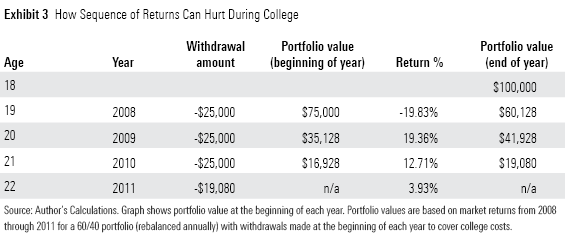

But because of the relatively short time period of a typical four-year college education, a year or two of bad returns at the wrong time can still create problems for more-balanced portfolios. The table below shows the potential impact of the 2008 bear market as an example. While the correction was pretty short-lived, it still would have had a lasting impact, even for a portfolio with a 40% stake in bonds. The bond position helped buffer some of the losses, but the portfolio would have still shed about 20% of its value in 2008. Even with positive total returns for the next three years, the portfolio would have fallen short of the amount needed to cover planned withdrawals of $100,000 over four years.

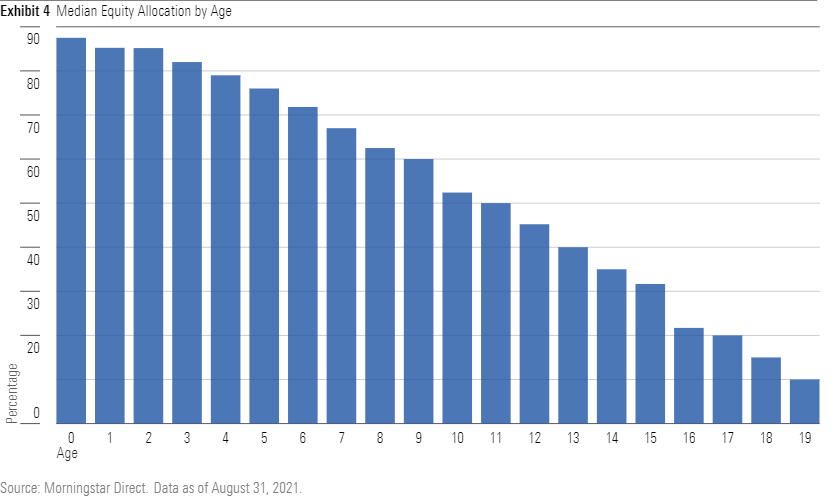

To avoid this problem, it makes sense to shift toward a much more conservative asset mix in the years leading up to college. As mentioned above, age-based and target-enrollment portfolios can be a sensible, low-effort way to keep risk exposure at the right level. Almost all 529 plans offer these options, which automatically shift their asset mixes more toward cash and bonds as the beneficiary approaches college age.

A typical asset mix would be mostly equity starting at birth, gradually shifting down to about 60% in stocks at age 9, 40% at age 13, 30% at age 15, 20% at age 17, and 14% at age 18. Not every age-based track makes gradual adjustments, though. Age-based tracks shift their equity exposure on predetermined dates, and some age-based tracks (such as Iowa's growth track) sell out of 20% or more in stocks on a single day. If stocks happen to sink on the same day, 529 plan owners could end up effectively locking in those losses, exacerbating the risk of a shortfall.

Many 529 plans also offer options for different levels of risk, typically labeled as aggressive, moderate, and conservative. The aggressive option for Utah's 529 plan, for example, targets 70% equity exposure for age 10, compared with 50% for the moderate track and 30% for the conservative option. Choosing the right mix is a matter of personal preference but also depends on each family's circumstances. If you want to help finance postgraduate studies or plan to "overfund" the 529 plan with a view toward saving for future beneficiaries, tilting a bit more toward stocks might make sense, as long as you're willing to live with the additional risk.

Do-it-yourself investors can also build a more customized asset mix. In addition to age-based options, most 529 plans offer individual funds that can be used as building blocks for targeting a specific blend of stocks, bonds, and cash. One relatively straightforward option would be to focus more on stocks early on, then shift into a balanced fund combining stocks and bonds, and then gradually build up more bonds and cash during the high school years.

Conclusion

Planning for college can be an overwhelming task, and trying to avoid bad returns at the wrong time adds another layer of complexity. But making sure your college fund’s asset mix isn’t too heavy on stocks--especially as your child approaches college age--is one way to avoid an unexpected outcome.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IFAOVZCBUJCJHLXW37DPSNOCHM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/JNGGL2QVKFA43PRVR44O6RYGEM.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/GQNJPRNPINBIJGIQBSKECS3VNQ.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)