Vanguard Cuts Target-Date Fund Fees as Fidelity Continues to Gain Momentum

Investors win again as two target-date behemoths continue to go toe-to-toe over which one is cheaper.

Investing in low-cost target-date funds continues to get cheaper. On Sept. 28, 2021, Vanguard announced plans to merge the Vanguard Institutional Target Retirement series into the Vanguard Target Retirement series in February 2022, with the result that shareholders in both will pay less.

The merger makes sense as the portfolios of these legally separate funds are practically identical. The main difference between them, in other words, has been fees and investment minimums. The institutional version of the series has charged 0.09% for defined-contribution plans with at least $5 million. Plans below that threshold could invest in the investor series for 0.12% to 0.14%, depending on the target-date vintage. Meanwhile, investors outside of a defined-contribution plan have had a low minimum investment of $1,000.

Once the merger finishes, all shareholders will pay 0.08%, and there will be no plan-level minimum; investors outside of a plan will still have the $1,000 minimum. This puts the series on par with Schwab Target Index as the cheapest target-date series that don't have a minimum threshold at the plan level.

Vanguard's fee cut also makes it generally cheaper than the Fidelity Freedom Index series, which has emerged as the top competitor to Vanguard's low-cost target-date throne. Although Fidelity Freedom Index, which has a Morningstar Analyst Rating of Silver, does have one share class at the 0.08% price range and another at 0.06% for plans with at least $2 billion, as of Sept. 29, it still had a $5 million plan level minimum threshold, and its investor share class charges 0.12% across the series. Given Vanguard's announcement, we don't expect it to stay that way for long, though.

Fidelity Beating Vanguard's Retail Business at Its Own Game ...

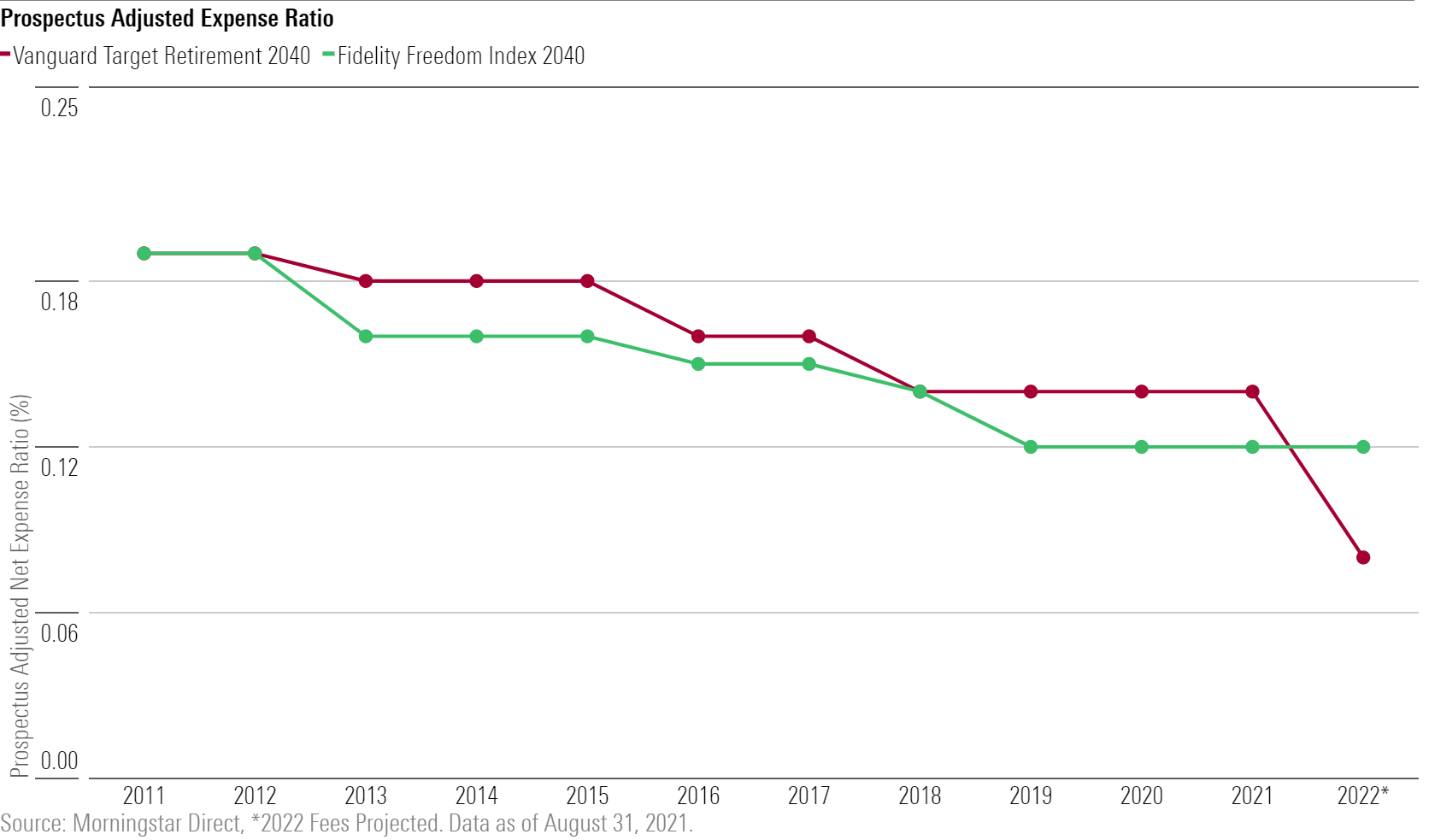

Fidelity hasn't been shy in keeping up with Vanguard's retail business when it comes to fees and investment minimums for its Freedom Index series. Exhibit 1 shows how the fees for the 2040 versions of the lowest-minimum-investment share classes of each series have trended over time, including the projected fees for the Vanguard series once it reaches its single-share-class state in 2022.

From 2012 through the September 2021, Fidelity was consistently cheaper, though never by more than a few basis points. Yet, following the merger, Vanguard will cost less for the first time in a decade.

History suggests Fidelity won't stay idle. In June 2015, for example, both series launched institutional share classes priced at 0.10%. When Vanguard dropped its fees to 0.09% in 2017, Fidelity then chopped its levy to 0.08% in 2018.

More recently, Vanguard cut its institutional shares' minimum investment to $5 million in December 2020 from $100 million previously. A month later, Fidelity made the same cut to its institutional shares' minimum.

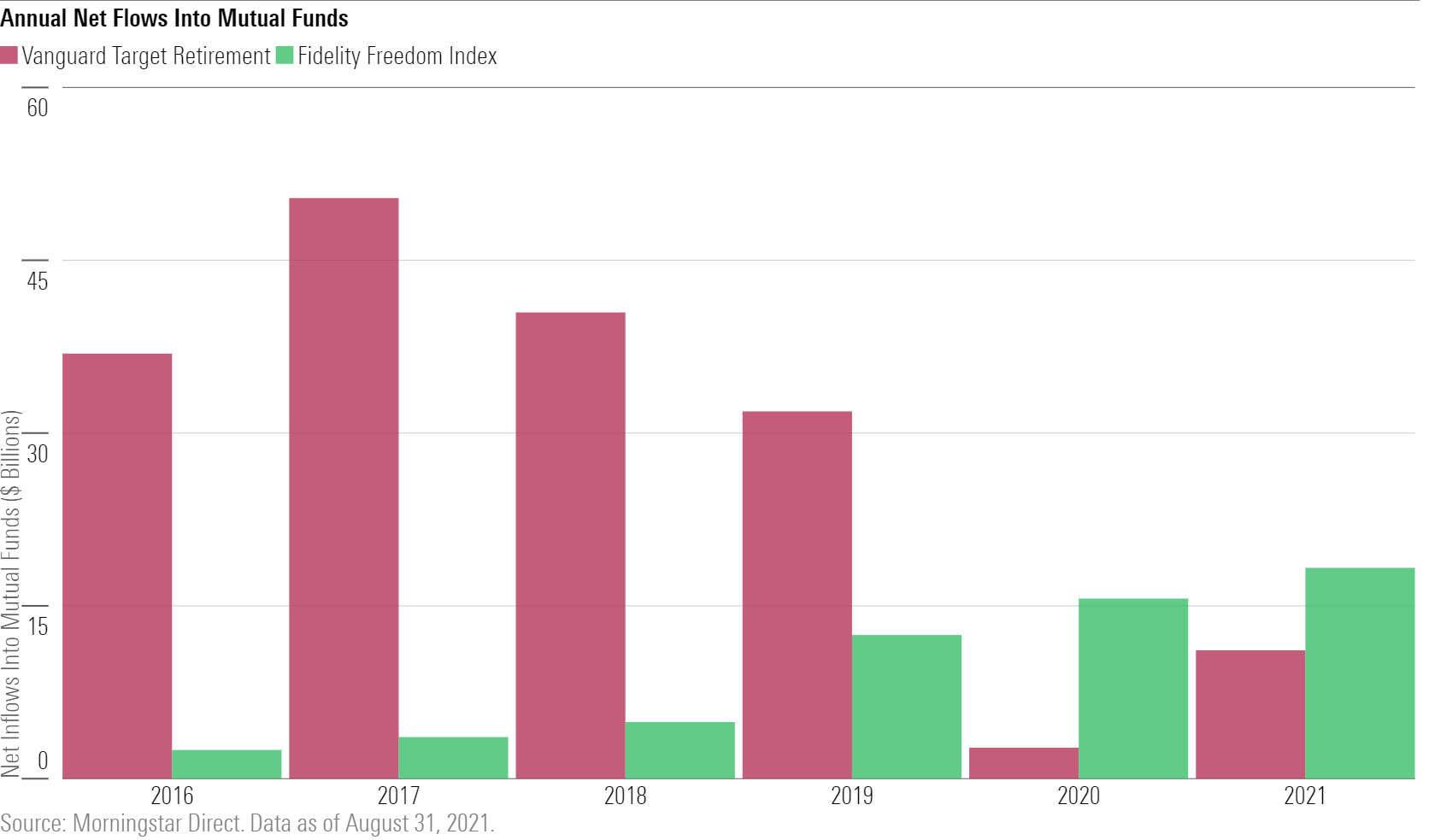

The competition has been a boon for Fidelity. Since 2020, Fidelity Freedom Index has supplanted Vanguard's retail business as the top index-based target-date series among mutual funds. Fidelity's net $34 billion of inflows into its index-based series nearly tripled Vanguard's $13 billion haul. It's a stark reversal from the previous two years, when Vanguard’s retail business brought in more than $70 billion of net inflows while Fidelity garnered less than $20 billion.

Exhibit 2 shows the annual flows into each mutual fund series since 2016.

… but Not With Larger Plans

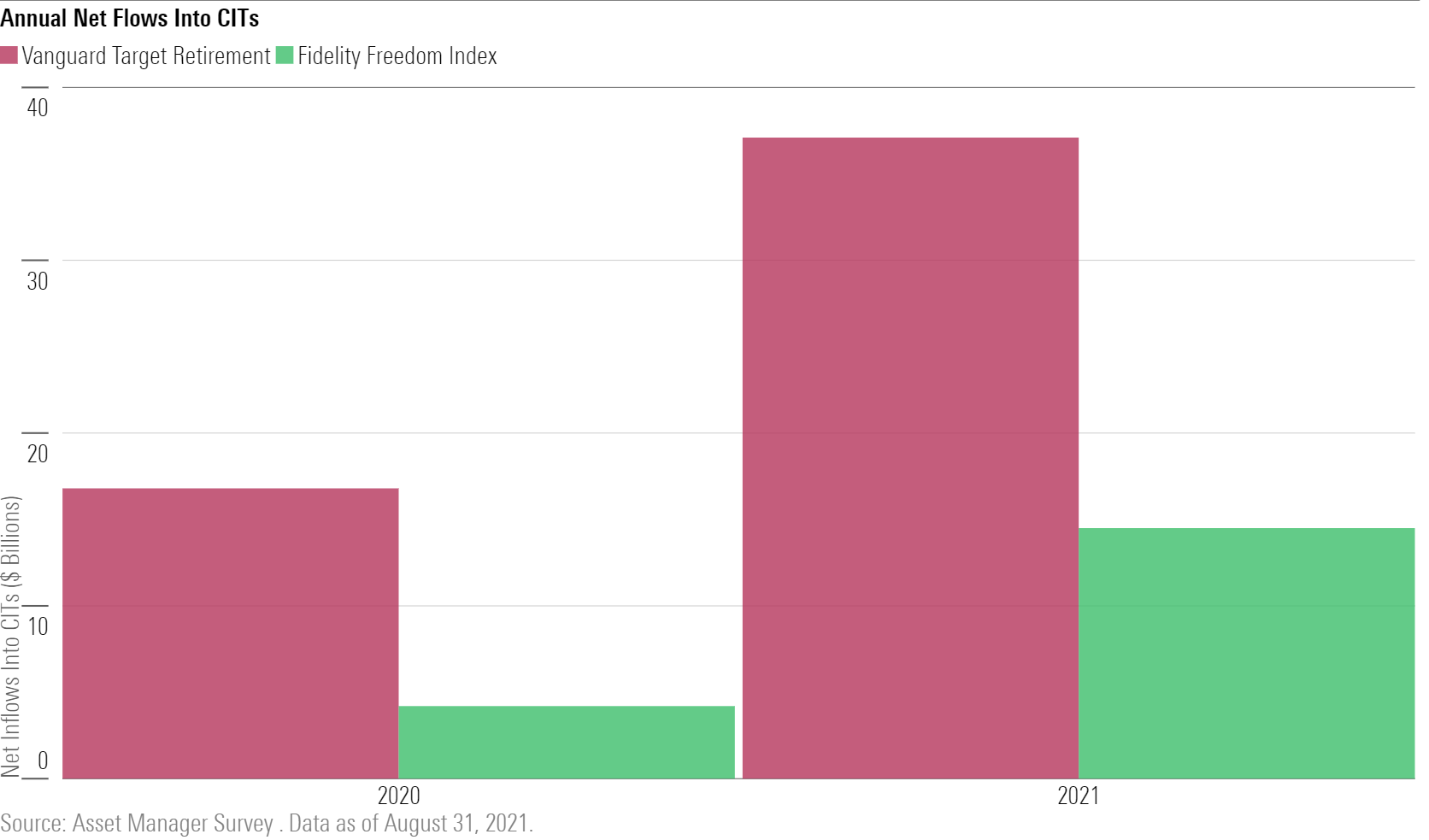

Fidelity's success has mostly been confined to mutual funds though. Vanguard has retained its lead when it comes to institutionally focused collective investment trusts, or CITs. These vehicles are only available through 401(k) plans and are most popular with the largest plans. That's because unlike mutual funds, plan sponsors can negotiate fees on CITs, and the largest plans use this to their advantage. Obviously, when the cheapest share class of the mutual fund is already as low as Vanguard's and Fidelity Freedom Index's, there's only so much room to lower fees. But when it's a multi-billion-dollar plan, every basis point counts. For example, for a $10 billion plan that had been paying 0.10%, a drop to 0.05% cuts the collective fees that participants pay from $10 million to $5 million from $10 million.

Exhibit 3 shows the flows into each series' CITs since 2020.

Since the biggest plans favor CITs, Vanguard's advantage with this vehicle has propelled it to larger overall flows in year-to-date 2021. Still, the momentum Fidelity has developed in target-date mutual funds is impressive.

The Tale of the Tape

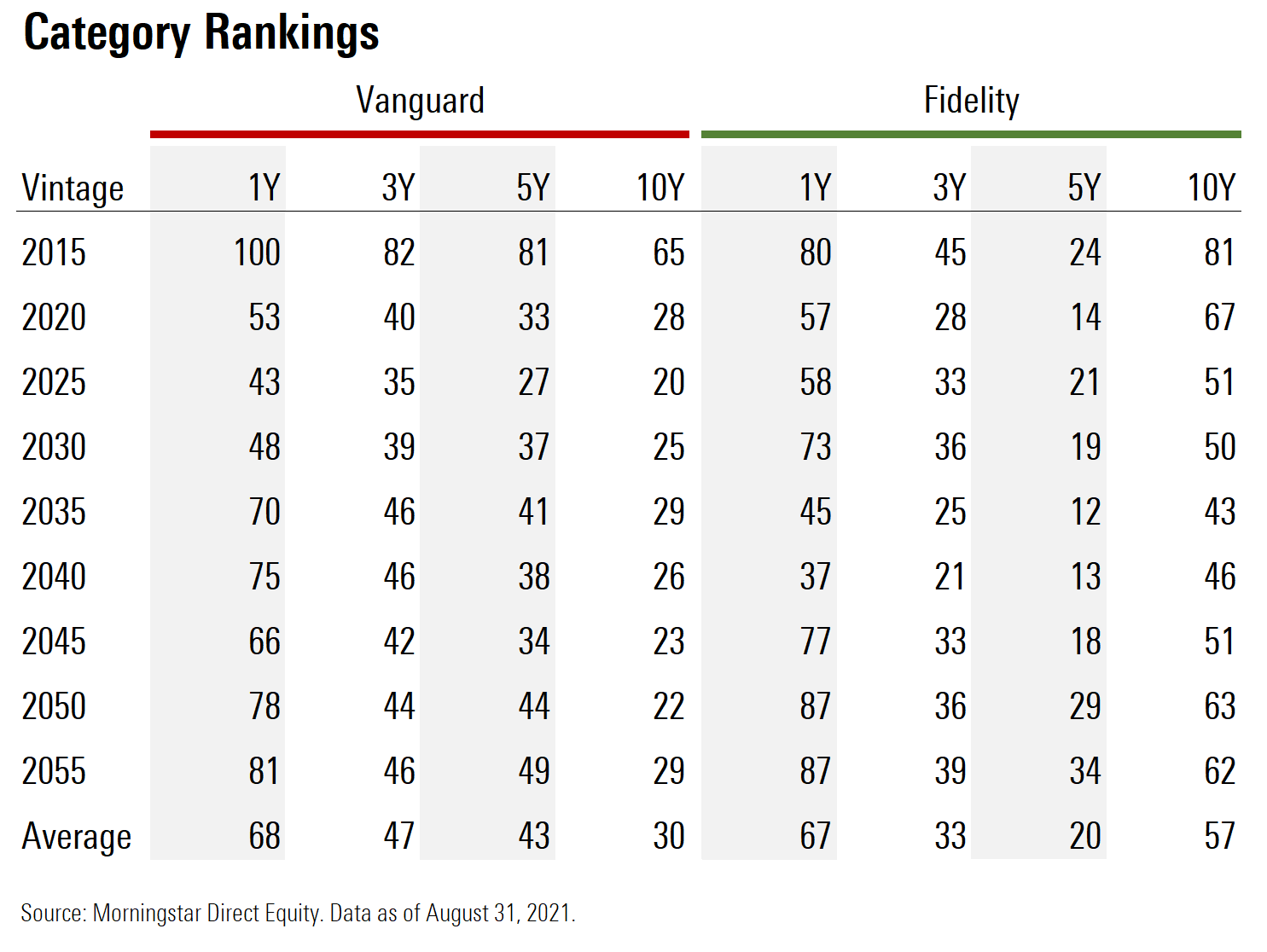

Recent performance may be driving some of Fidelity's momentum. Exhibit 4 shows the average Morningstar Category rank for each vintage of both series' investor share classes over major trailing periods.

Fidelity holds an edge over the past three and five years ended Aug. 31, though Vanguard still wins out over the longer 10-year period. Both have struggled over the trailing one-year period.

Each series holds 40% of its equity portfolio in international stocks, which is about 10 percentage points higher than the average target-date fund, and that's been a headwind as U.S. stocks have continued to outpace the rest of the world in 2021.

On the bond side, they've faced an additional challenge from rising interest rates, which has been a common pain for index-based target-date series.

It's All About the Bonds

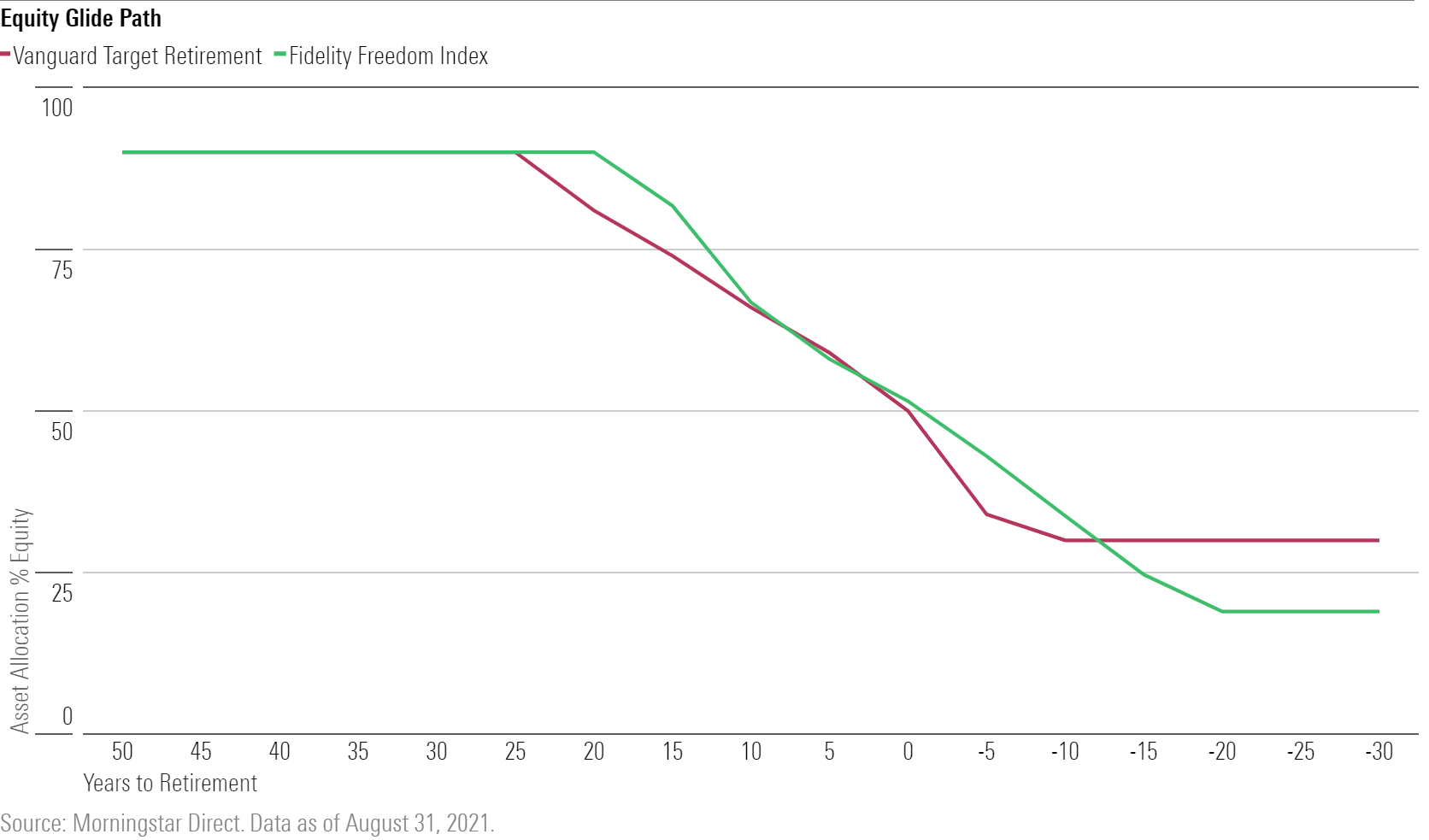

Going forward, the performance of the series' fixed-income portfolios will determine the ultimate winner, especially since both series' equity glide paths are also very similar, as Exhibit 5 shows.

Vanguard does start to lower its allocation to stocks a little sooner than Fidelity. After reaching the target date, it has one of the sharpest equity drops in the first five years of retirement before settling at its 30% equity landing point. That's 11 percentage points higher than Fidelity's. Yet, both have an average allocation of about 62% to stocks across the glide path, so the differences should even out over time.

The bond portfolios are very different, though. Vanguard invests 30% of its fixed-income portfolio in Vanguard Total International Bond VTIBX, which hedges out international currency exposure from its underlying bonds. Fidelity doesn't include any strategic allocation to non-U.S. bonds, though it does take a more nuanced approach by including long-duration U.S. Treasuries, which have historically been a strong diversifier for portfolios with lots of equity exposure.

A Win-Win for Investors

Given their low costs and broad straightforward portfolios, both series have considerable appeal, as signified by their Analyst Ratings of Silver, which indicates one of our highest conviction levels in a target-date strategy's ability to outperform its category benchmarks on a risk-adjusted basis. That Vanguard and Fidelity are competing on price is ultimately a win for investors in either, who will get to keep more of what of each series earns.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/af89071a-fa91-434d-a760-d1277f0432b6.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/4TYZEEXD3RGWNKTVNUJBWDUFAM.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZP7H3U7MTNHJ5H3WWEUKGBUQGE.jpg)