When Indexing Is Not an Improvement

The curious case of target-date funds.

An Overstatement?

Friday’s column, “The U.S. Needs Only One 401(k) Plan,” maintained that, after 40 years’ worth of experience, the marketplace has determined the correct structure for defined-contribution plans. Default new employees into target-date funds that are based on underlying indexes. That will suffice for most investors. Meanwhile, those who wish to make their own decisions can select from a menu of single-asset index funds. For even greater flexibility, they can open a brokerage window.

The article elicited several emails from financial advisors who serve 401(k) plans. The responses were notably polite, given that my suggestion, if adopted, would scuttle their businesses. (Then again, why not humor the crank?) One comment immediately struck me. The reader wrote, "Clearly, broad-based index funds have outperformed most actively run funds in a similar category. But actively managed target-date funds have outperformed the indexed versions."

That claim deserves attention. If it is correct, then Friday’s article overstated the argument for indexing within defined-contribution plans. The case for indexing single assets, such as large-company U.S. stocks or investment-grade bonds, has been amply established. But should 401(k) plans also index with their target-date funds? I had assumed so, but I had not closely examined the numbers. Let’s do so now.

Vanguard Versus the Masses

For simplicity’s sake, this article will evaluate the 10-year results of a single target-date category: 2030 funds. However, as I checked the findings against other target-date categories, I can attest that its conclusions apply to all flavors of target-date funds, save for those shares that are designed to be held after the maturity date, during retirement. (Although retirement shares technically belong within a target-date series, they are different animals.)

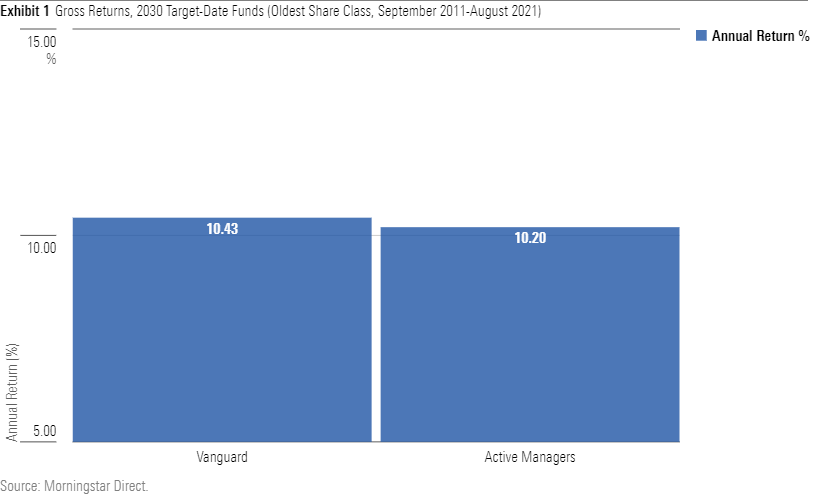

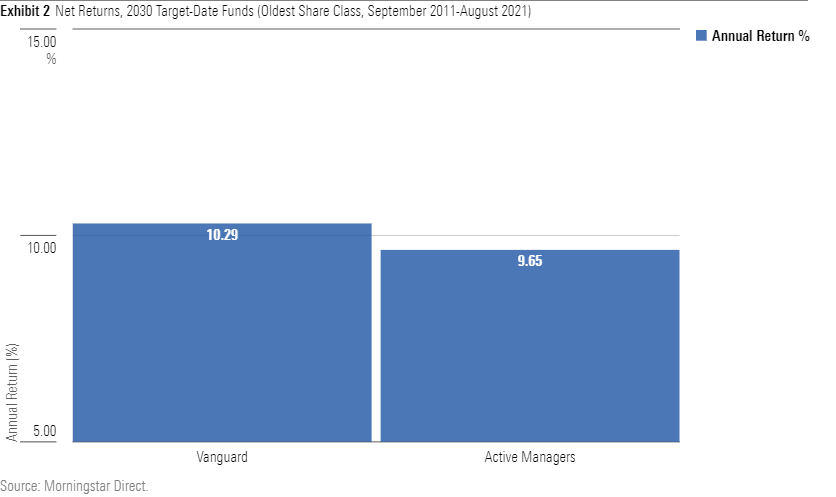

The first view presents gross returns: the funds’ total returns plus their expense ratios. Of course, shareholders cannot spend gross returns, but considering them is a useful starting point for understanding the causes for any performance differences that may exist. The following chart shows the 10-year gross returns for two groups: 1) Vanguard Target Retirement 2030 VTHRX, and 2) the average for all 2030 target-date funds that hold actively managed underlying investments.

This result echoes most indexing-versus-active comparisons. Before expenses, the two groups perform almost equally. Some active managers make more winning than losing trades, while others miss more often than they hit. It all washes out. On average, the active funds end up being just about average, albeit slightly handicapped by their additional trading costs and their higher cash positions.

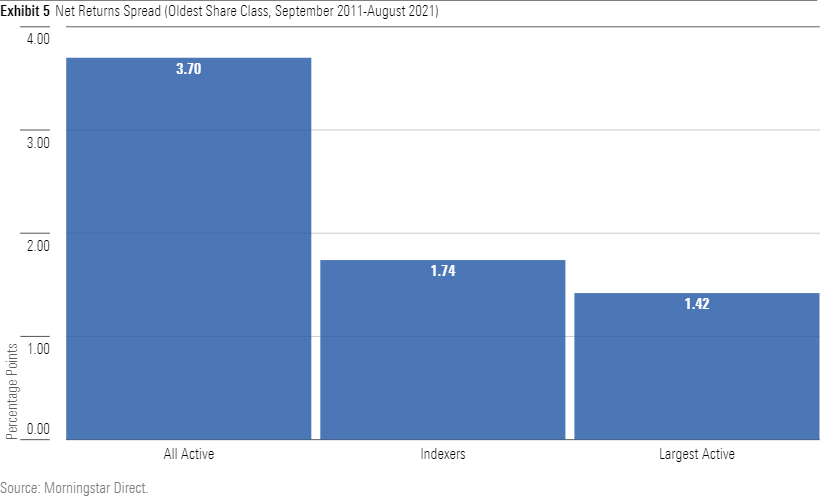

Indexing’s true benefit comes from charging less. The Investor shares for Vanguard’s 2030 fund carry an all-in expense ratio of 0.14%, as opposed to 0.55% for the oldest share classes from Vanguard’s actively managed rivals. Forty-one basis points of cost advantage plus 23 basis points of extra gross returns creates a net margin of 64 basis points per year--a comfortable amount.

Vanguard Versus the Leaders

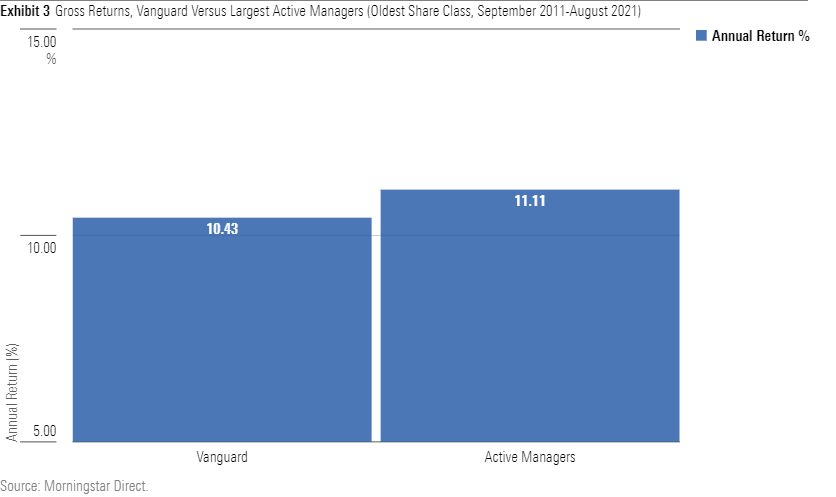

However, this preliminary outcome is stacked. Vanguard is but one of several companies that indexes its target-date series. Meanwhile, the actively managed list includes all qualifying funds, including several that hold less than $1 billion in assets. (In contrast, Vanguard’s 2030 target-date funds possess $108 billion.) What if, instead of selecting the entire list of actively run funds to compare against the market leader for indexing, we choose only the major competitors?

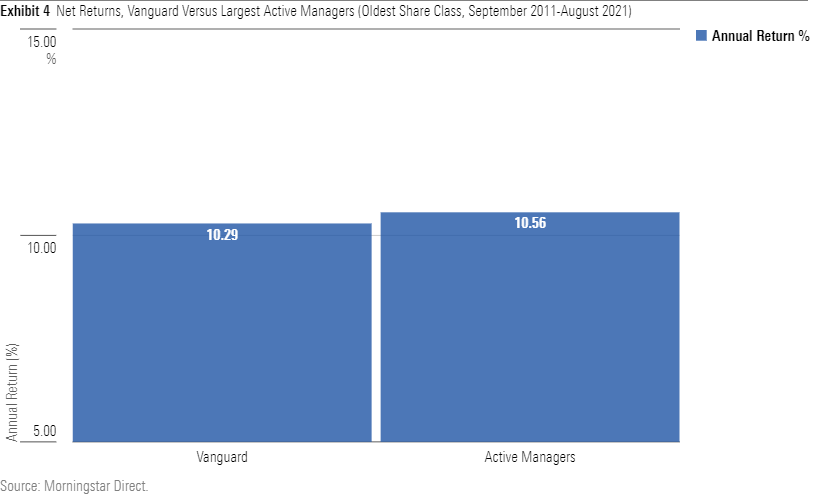

Doing so leads to a different conclusion. The five largest actively managed target-date 2030 funds come from Fidelity (FFFEX), American Funds (REETX), T. Rowe Price (TRRCX), Principal (PMTIX), and JPMorgan (JSMIX). (Screening based on their current assets doesn’t affect the outcome, because they were also among the biggest a decade ago.) Size, it turns out, has been a proxy for quality. Unlike with the overall actively managed group, the gross returns from these five funds have exceeded those from Vanguard 2030.

To be sure, Vanguard’s fund retains its cost advantage. The largest funds charge the same amount as the other actively managed funds, at 0.55% per year, thereby giving Vanguard that same 41-basis-point initial lead. This time, though, Vanguard’s lower expense ratio is not enough. Even after accounting for the cost difference, the five largest funds outgained Vanguard’s offering.

Looking Forward

When the analysis is limited to the industry’s leaders (defined as Vanguard for indexers and the five largest providers for active managers), the reader is correct: The active target-date funds had higher returns. Their margin of victory is modest, however. In addition, after volatility is considered, Vanguard holds a slight edge, as its 10-year Sharpe ratio is 0.98, while the five active funds averaged 0.96.

Call it a draw. When forecasting the future, place those six families' target-date funds in a hat. Your guess about which fund will lead and which will lag is as good as mine. True, Vanguard's fund will continue to boast lower costs. Against that advantage, though, must be weighed the demonstrated ability of its top actively managed rivals (which, once again, were on top before they posted their 10-year returns), plus the reality that with target-date funds, there are no purely passive strategies. When setting its funds' asset allocations, even Vanguard is active.

Because of the latter point, there are marked differences among target-date funds among index providers. Whereas one index fund usually looks much like another, asset-allocation disparities negate that tendency with target-date funds. Indeed, the gap between the highest and lowest 10-year returns among indexed 2030 funds is higher than the gap for the five largest actively managed funds. True, the difference is even steeper when considering all actively run 2030 date funds, but plan sponsors need not choose from the entire universe.

Final Words

In short, Friday's column was a bridge too far. It is true that 401(k) plan sponsors increasingly favor index funds, because they have observed the practice's general success, to lower their plans' costs, and they hope that indexing will prevent lawsuits for fiduciary malpractice. For those reasons, indexed target-date funds will continue to grow their market share. But that is different than stating that they should become more popular. The evidence does not support that belief.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)