For Retirees, Buying and Holding Bonds Isn’t So Simple

The investment math is surprisingly messy

Seeking Income

Broadly speaking, bonds fulfill two purposes.

For workers, bonds build wealth. They diversify portfolios that build for the future. How bonds deliver their results is immaterial. What matters is that they outgrow inflation while protecting against stock-market declines.

For most retirees, things are different. Retirees expect bonds to provide income. True, some invest for total return, dipping into capital as required, but clipping coupons from high-quality bonds is easier. Buy Treasuries, spend the distributions, and don’t touch the principal. What could be simpler? All receipts are stipulated in advance, guaranteed by the United States government.

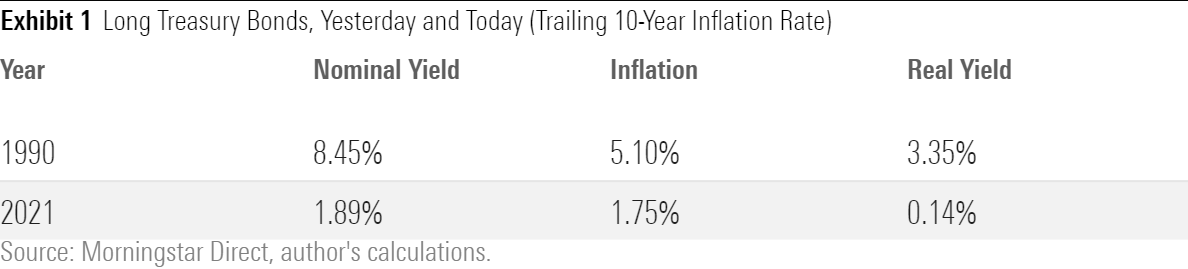

This strategy can be very successful. Consider, for example, the opportunity facing December 1989’s retirees, when 30-year Treasuries yielded 8.45%. True, inflation had averaged 5.1% annually over the previous decade. If it continued at that level, the long bond’s real income would be appreciably lower than its stated payout. However, its steep yield offered adequate compensation, barring a further rise in inflation. In contrast, today’s 30-year Treasury leaves no room for error.

Making It Real

Even in 1990, though, buying and holding Treasuries required forethought. A 3.35% real yield is excellent. With that return, investors can not only hold their own against inflation, but also grow their purchasing power. Except … they can’t. That 3.35% figure applies only in the year the bond is first acquired. Thereafter, the margin shrinks, as the bond’s distributions remain constant while the effects of inflation accumulate.

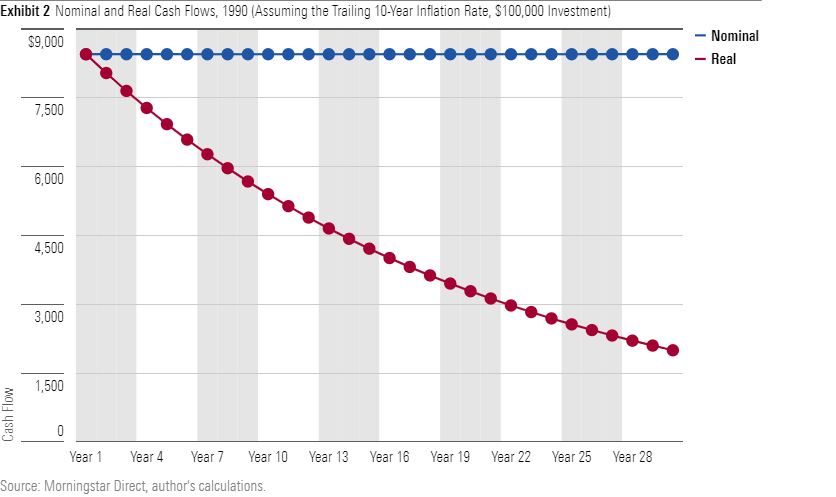

The chart below portrays the difference between the bond's nominal payments and its real outlays, assuming a $100,000 initial purchase. (When determining the real cash flows, I used the trailing 10-year inflation rate, rather than what actually occurred over the ensuing 30 years, because, lacking Gray's Sports Almanac, 1989's retirees did not know what the future would bring.)

So far, so familiar. Even noninvestors are at least vaguely familiar with the ravages of inflation. Not many people, though, have attempted to calculate how they might smooth their fixed bond payments so that they receive stable real cash flows. (My UCLA-educated stepfather certainly did not, nor from my recollection did his friends, most of whom emulated him by retiring on a combination of Social Security payments and income from their bond portfolios.)

Let’s try. Because the after-inflation value of the bond’s payments declines over time, the process of creating a single, consistent withdrawal rate involves setting aside money today to be used later. Initially, our retiree will spend less than her annual $8,450 payment, reserving the remainder for future years, when she must withdraw ever-larger sums to retain the same purchasing power. But how much less? What is the break-even amount?

For Example

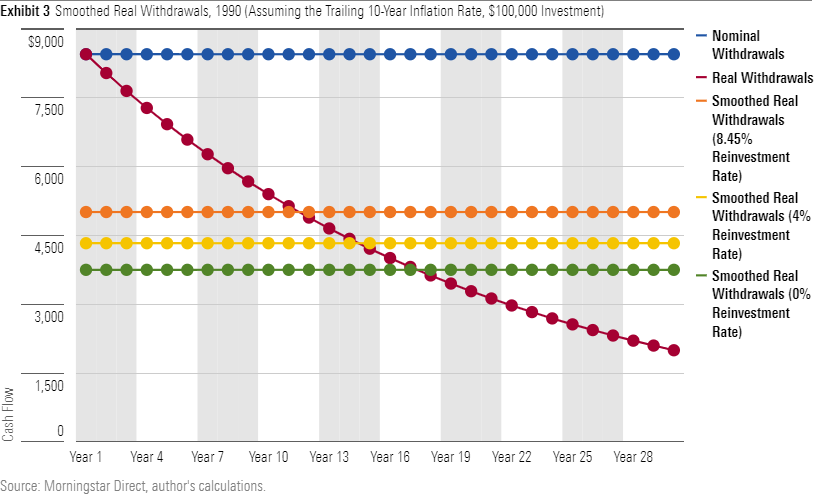

Regrettably, those questions cannot be answered. The calculation requires two inputs that cannot be known in advance, one being future inflation and the other the interest rate that applies to excess proceeds--that is, the reinvestment rate. Nonetheless, I will present some possible answers after making two simplifying assumptions. First, I will continue to use the 5.1% inflation rate rather than model alternatives that 1989’s investors might have considered. Second, I will evaluate three reinvestment rates: 1) the bond’s original yield of 8.45%, 2) a more conservative value of 4%, and 3) the lowest possible rate of 0% (the mattress).

What those results mean: If the retiree could buy more of her bond at the original price, thereby receiving an 8.45% annual payout on the excess cash, then she could spend an inflation-adjusted 5.01% per year. In year 1, she would spend $5,010 of the initial $8,450 payment while saving the remaining $3,440. Those dollars would increase over the next 12 months to become $3,731, thanks to the 8.45% interest rate. The next year, the retiree would spend $5,266 (the figure being slightly higher owing to inflation) and pocket the rest. And so forth.

In year 20, the excess proceeds would reach their peak value and then recede. (That crossover is not portrayed on the graph, so don’t squint trying to find it!) The downturn occurs more rapidly than the rise, because after several decades the number of nominal dollars required to maintain real spending becomes alarmingly high. In this case, the year 30 withdrawal is $21,199--more than 4 times the year 1 amount and 150% above the bond’s nominal yield.

The logic is similar when the reinvestment rates are 4% and 0%, but of course the withdrawal rates are lower, at $4,330 and $3,750, respectively. Pity the retiree who belatedly realizes that the apparent simplicity of buying and holding Treasury bonds is illusory. What really matters are real receipts, but estimating them leads to wide disparities, depending upon one’s assumptions.

Looking Ahead

This was a relatively easy exercise, because Treasury bonds can neither be called nor (absent circumstances too dire to contemplate) will they default. Investing in other bonds complicates the analysis, as does treating inflation more realistically. For these projections, I assumed that the next 30 years’ inflation rate would match that of the past decade. That’s an acceptable starting point, but as the post-1989 history demonstrated, other possibilities should properly be tested.

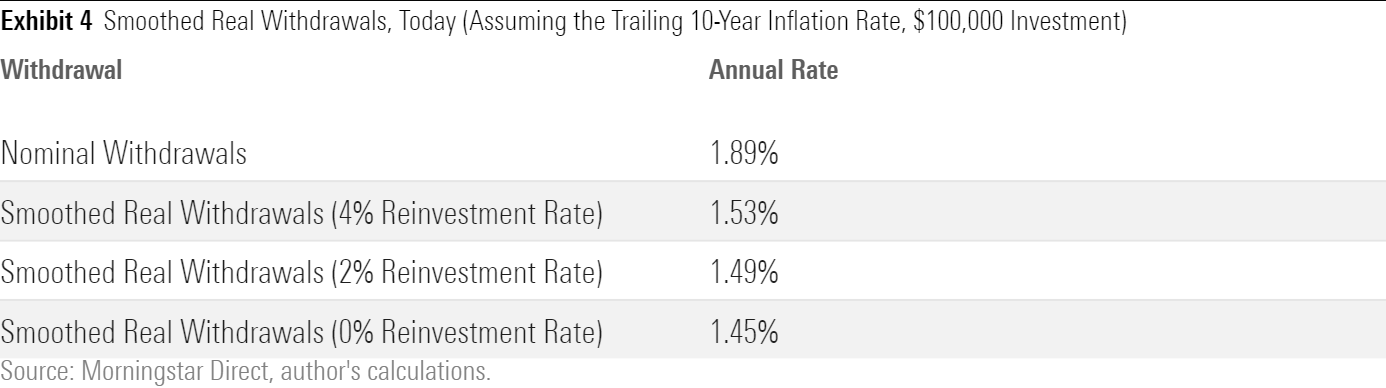

The good news for 2021’s freshly minted retirees is that there is less uncertainty with Treasury bonds than there was three decades go. Unfortunately, that is because today’s Treasury payouts are paltry. With a yield of just 1.89%, the 30-year Treasury generates little cash. Its reinvestment risk is therefore low--but so, under all reasonable interest-rate projections, is its real withdrawal rate.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/6ZMXY4RCRNEADPDWYQVTTWALWM.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)