The Long-Term Forecast for U.S. Stock Returns

Expect 7.5%.

3 Factors

Returns for U.S. stocks have been erratic in the short run, but they are reasonably foreseeable over the long haul.

By “long haul” I mean several decades. True, many investors will not survive that horizon, but nevertheless the knowledge that equities perform predictably over prolonged time is useful. It provides ballast, reassuring shareholders after poor equity performances and grounding them when it seems that stocks cannot lose.

Warren Buffett supplied the math. Stock returns consist of dividend receipts plus price changes. Dividend yield is apparent. The amount of price change is trickier to determine, but ultimately the stock market reflects reality, by tracking the growth in real corporate earnings. To that must be added the effect of inflation. The formula for forecasting long-term stock returns is therefore: 1) current dividend yield plus 2) expected real earnings growth plus 3) expected inflation.

Since Truman

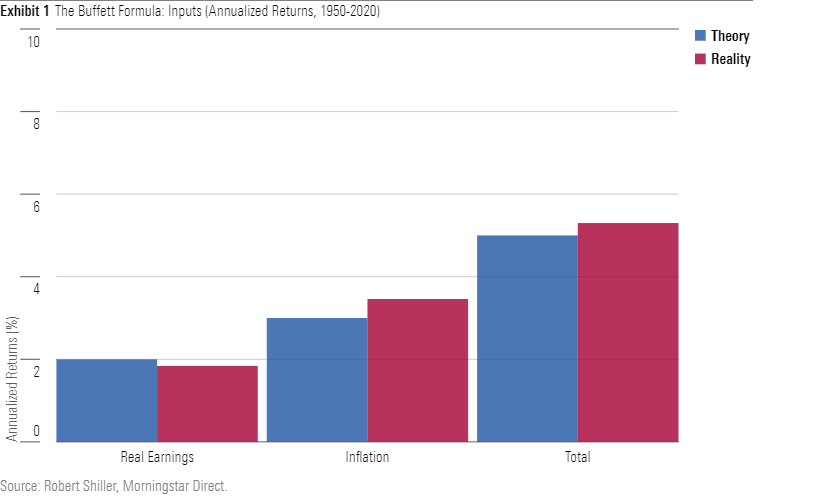

Per the history, stated Buffett, investors should expect an annualized 2% in real earnings growth and 3% for inflation. While we can't test whether those estimates will hold for the future, we can judge whether Buffett has accurately described the past. The chart below depicts the average real earnings growth for the S&P 500 and inflation rate (earnings data courtesy of Professor Robert Shiller) for the 71-year period from 1950 through 2020 compared with Buffett's numbers.

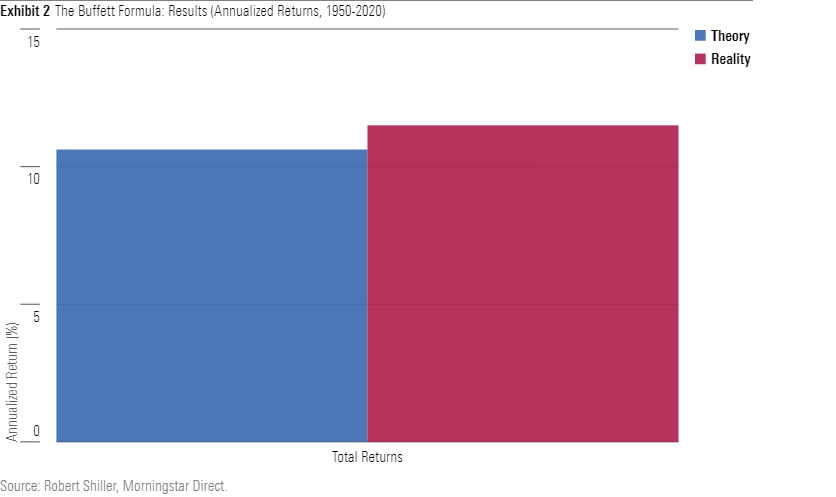

Pretty much a match. Past earnings growth was slightly below Buffett’s seemingly unassuming figure, and past inflation slightly higher, with the combination landing three tenths of a percentage point above his estimate. Because those two factors nearly matched expectations, one would think that, if retroactively applied in 1950, Buffett’s formula would have worked. Entering that year, the dividend yield on the S&P 500 was 5.62%. Thus, future stock returns should have been 10.62%.

Once again, not far off the mark. The gap between forecast and actual performance was 88 basis points. We have already identified 30 basis points of that difference. The remaining 58 basis points owe to two offsetting factors: 1) dividend yields fell during the period, thereby lowering returns, but 2) price/earnings multiples expanded, thereby boosting returns. For the most part, those items canceled each other out, making Buffett’s formula largely accurate.

A Closer Look

Of course, Buffett had the benefit of hindsight. A sterner test of his method would be to examine several shorter periods to assess the consistency of results.

We don’t need formal analysis to know that Buffett’s inflation plug oversimplifies, as inflation rates have varied widely. However, because corporations compensate for inflation by raising their prices, thereby preserving their real earnings power, the accuracy of that estimate isn’t terribly important. If long-term inflation is 5% rather than 3%, stocks will likely gain an additional 2 percentage points, and if long-term inflation is 1%, they will likely make 2 points less. No harm, no foul.

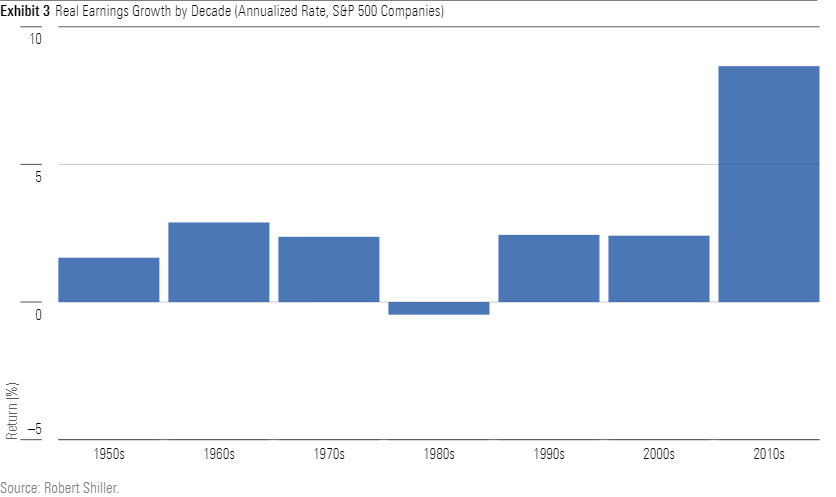

What really matters is the stability of earnings growth. If the increase in corporate earnings has been as capricious as inflation, then predicting stock returns requires economic guesswork. The forecaster must understand and accurately assess how corporate earnings will evolve. That is a formidable task. If, on the other hand, the increase in corporate earnings has been steady, varying little from one decade to the next, then one can reasonably assume that the future will resemble the past.

In no decade save for the 2010s did real corporate earnings growth exceed 3%, and in none but 1980s did it fail to reach 1.5%. (Stocks rallied during the Reagan administration on the news of declining inflation, but it took corporations a few more years to convert that benefit into higher earnings.) Among those two exceptions, only the former truly stands out. That result thoroughly upsets the thesis. It seems that the rule of 2% real earnings growth has been broken.

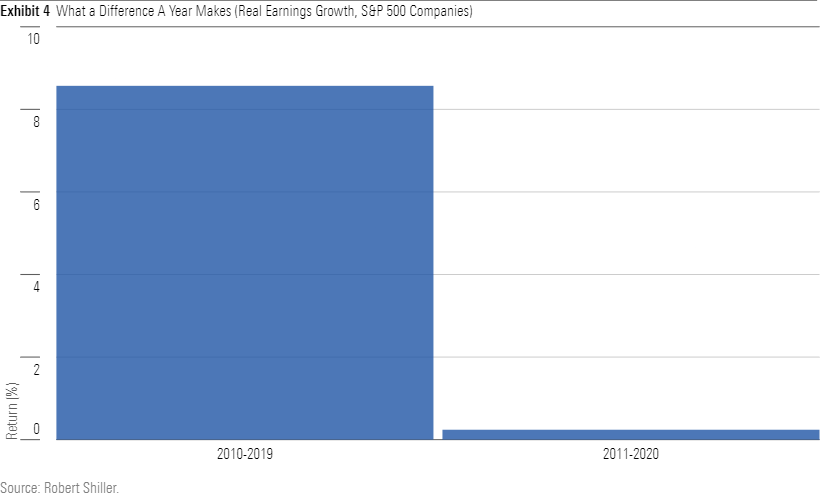

That impression, however, is false--a database mirage. Real earnings growth during the 2010s was unprecedentedly steep because December 2009 earnings were abnormally low, following the global financial crisis, while December 2019 earnings were a pre-pandemic peak. Shift the measurement by a single year, so that it evaluates 2011 through 2020, and the decade’s apparent success vanishes.

The 7.5% Solution

The new normal looks much like the old normal. Such is typically the case. Real earnings growth during the 2000s was no higher than during the 1960s. To be sure, productivity has improved substantially over those 40 years, but those gains were already reflected in stocks’ performances. Corporate improvements come gradually. There’s no compelling reason to expect otherwise in the future.

Which means that the Buffett formula would appear to remain valid. With the S&P 500 currently yielding 1.37%, the model gives an expected long-term stock return of 6.37%. However, one further consideration is required. Corporate stock buybacks, which effectively substitute for dividend payouts, are near record levels, accounting for 1.6% of the S&P 500’s market cap during 2020.

Adding that amount to the 6.37% estimate pushes the projection to 8%. However, we need to shave that figure because companies also repurchased their shares in the past (albeit only since the 1980s). Knocking 50 basis points off the addition for the buyback activity places the long-term forecast for the S&P 500 at 7.5%.

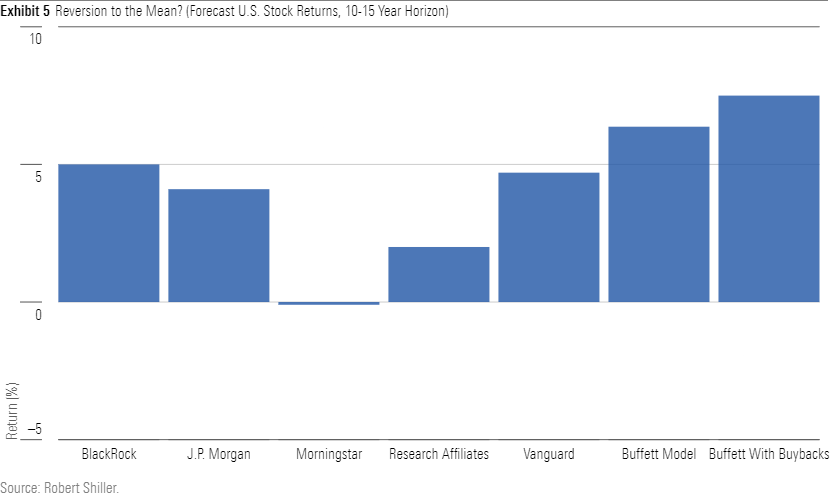

Such a prediction is seemingly contradicted by five institutional researchers, including Morningstar itself. In January’s “Experts Forecast Stock and Bond Returns: 2021 Edition,” by Christine Benz, each researcher’s forecast trailed even the raw Buffett estimate of 6.37%, never mind the modified amount of 7.5%.

The discrepancy is more apparent than actual, however. The researchers’ estimates cover the next 10-15 years, during which they expect today’s sky-high stock valuations to revert to the mean. Their long-term forecast for equity returns would therefore be significantly higher. At least in the case of BlackRock, JPMorgan, and Vanguard, I would expect those figures to pretty much match this column’s 7.5% estimate.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WC6XJYN7KNGWJIOWVJWDVLDZPY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HHSXAQ5U2RBI5FNOQTRU44ENHM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/737HCNGRFLOAN3I7RKGB7VPEKQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)