From the Archives: Why Target-Date Funds Don't Resemble University Endowment Funds

Half the reason is legal, the other half is practical.

This column was originally published on Sept. 20, 2016.

A World Apart

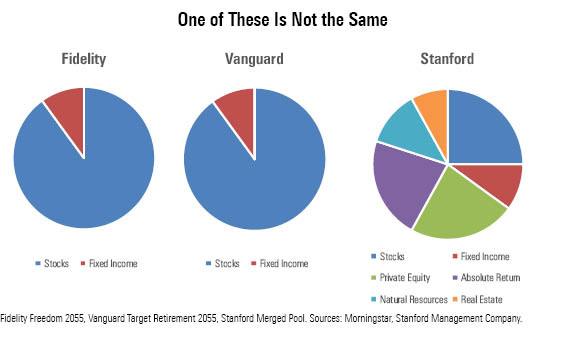

Target-date mutual funds don't look anything like the major university endowment funds.

The disparity would seem to be a puzzle. Dissimilarity between endowment and target-date funds would be understandable with, say, 2025 funds, which have a relatively short time horizon. But why would a 2055 fund not resemble an endowment fund? At 39 years, the target-date fund's time horizon is long enough to permit any investment approach. And if the 2055 fund sometimes requires liquidity (to meet redemption requests), so, too, does the endowment fund (to meet its university's spending needs).

But diverge they do. Compare the asset allocations for the 2055 funds from the two largest target-date families, Vanguard and Fidelity, with that of Stanford's endowment fund. (I selected Stanford at random; I wanted a large fund from a top university and not the usual example of Yale.) The two mutual funds are peas in a pod. Stanford's fund is something else altogether.

It's the Law

There is, to be a sure, a large difference caused by regulations. Because they are governed by the Investment Act of 1940, target-date funds cannot hold more than 15% of their assets in nonpublic securities--which is the only way that private equity investments are packaged. Endowment funds face no such restriction. They may own as many or as few private securities as they desire.

Thus, there's no way for target-date funds to match Stanford's 23% exposure to private equities. The highest private equity position that a target-date fund could achieve would be 15%, or two thirds of Stanford's stake--but only if that target-date fund used its entire permitted allotment of private placements solely on that asset class. (No target-date fund has made such a choice.)

Target-date funds also cannot fully emulate how Stanford invests for its commodities and natural-resources exposures or with its absolute return strategies. To be sure, all three asset types are readily available as public securities. Target-date funds can own the stocks of commodity/resource companies, exchange-traded funds that trade commodity futures, or registered mutual funds that seek absolute returns. So, target-date funds can get all the way to Stanford's combined 20% allocation, if they wish.

Target-date funds cannot do so, however, while using a full tool kit. In addition to publicly traded real estate investment trusts, endowment funds may garner their real estate exposures through private-placement securities, which give direct property ownership. So, too, may they hold their natural resources; for example, they may purchase a stake in a timber reserves. And, of course, endowments may use private hedge funds for their absolute return allocations.

And It's Habit

While regulations partially address the puzzle, they are not the entire answer. Yes, target-date funds must invest 85% of assets into publicly held securities, thereby limiting their options, but it is not as if this is 1975 and mutual funds come in vanilla, chocolate, and strawberry. ETFs, in particular, come in a wide variety of flavors. Target-date funds certainly could invest 20% (or more) in alternatives, if their managements wished, and make liberal use of private equity. They could also try some of the newer institutional investment practices, such as momentum strategies or low-beta investing.

This, in fact, is advocated by three authors from AQR Capital Management in "Balancing on the Life Cycle: Target Date Funds Need Better Diversification." Published in The Journal of Portfolio Management, the article proposes that target-date funds goose their staid mix of U.S. stocks, foreign stocks, and bonds/cash by adding commodities, managed-futures trading strategies, risk parity, and volatility targeting.

The paper finds that, in a back-test, the authors' spruced-up portfolio outgained a traditional balanced portfolio (60% stocks, 40% bonds) by 3.5 percentage points per year while being less risky. Of course, the victory margin for the authors' portfolio would have been smaller over the more stock-heavy, 90/10 mix that is used by 2055 target-date funds--but its risk advantage would have been even greater.

This paper, of course, does not prove that Stanford's portfolio is superior to those of the leading target-date funds, as neither Stanford nor target-date funds were its subject. Indirectly, though, it suggested that, looking backward, the fancier endowment-fund model--the model that embraces alternative investments, enhanced diversification, and a greater willingness to try new investment schemes--has outperformed the simpler target-date approach.

Asking Questions

Will the endowment approach be better than the target-date path looking forward? Of that I am considerably less optimistic.

For one thing, the investment results are likelier to be closer--at least from those published in the AQR paper. The logic that underlies the endowment effect is sound because of the reduction in portfolio volatility that comes from adding new varieties of risky assets, but it must also be confessed that studies like AQR's involve some cherry-picking. The tactic of risk parity, for example, is included in part because it did work well in the past.

But the main concern is not total returns. It is the reaction to performance by those who own the target-date funds (shareholders) and, even more, by those who selected the funds (the plan sponsor). A complex investment strategy, with many moving parts, means more wheels that are stuck at any given time, leading to more questions and more uncertainty. If a target-date fund adopts an endowment model, there will be times when it badly lags other target-date funds. And there will be other times when its lack of portfolio liquidity proves problematic.

The latter might have been the case in 2009, when Stanford's fund sought to sell $1 billion worth of its private-placement securities at what would have been fire-sale prices. (Management denied that its action constituted a forced sale and took those assets off the market when it failed to receive what it regarded as an acceptable bid.) The former might have been the case in 2015, when the Stanford fund's new CEO fired almost the entire investment staff.

Explaining the performance of a complex portfolio can be hard enough within an institutional setting, with the relatively few listeners being relatively knowledgeable about investing. It is that much more difficult in a public (and political) setting. Target-date funds will be cautious indeed about adding endowment-style wrinkles. As they should, from the practical perspective. After all, no fund ever made money for an investor who departed.

Addendum: Since this column was published, the investment trends have strongly favored target-date funds. For the trailing 10 years ended June 30, 2020, the average annualized rate of return for the 2040 target-date mutual funds in Morningstar's data base was 9.5% as opposed to 7.5% for the typical endowment fund. Score one for the investment masses--for now.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZKOY2ZAHLJVJJMCLXHIVFME56M.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IGTBIPRO7NEEVJCDNBPNUYEKEY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HDPMMDGUA5CUHI254MRUHYEFWU.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)