The Morningstar Rating for Funds: What to Know

Sometimes past performance is indeed predictive, and then so is the star rating.

From the Beginning

There are two versions of the Morningstar Rating, or star rating: one for funds, and the other for stocks. This column concerns the former, as the latter is quite different.

The star rating was first used for mutual funds shortly after the company's 1984 inception. At that time, investors evaluated funds almost solely by their total returns. As a freshly minted MBA, Morningstar's founder Joe Mansueto had learned from his professors that investments should be measured by risk-adjusted performance, not by returns alone. Thus was born the star rating.

The rating was instantly popular because although its computation was messy, the picture was simple. Five stars, excellent. One star, poor. The rating system became a fixture. When Morningstar expanded its coverage to include other types of funds, such as closed-end and exchange-traded, so did the star rating.

In the early days, Morningstar spent much time explaining how the star rating differed from the academic standard for risk-adjusted performance, the Sharpe ratio. That effort was wasted. As William Sharpe himself pointed out, the two measures offer nearly identical conclusions. If one fund has a higher star rating than another, it almost certainly has a higher Sharpe ratio as well.

Switching to Categories

What matters instead are the peer groups. At first, Morningstar compared funds very broadly. There were only four ratings buckets: 1) U.S. stock, 2) foreign stock, 3) taxable bond, and 4) municipal bond. (Allocation funds, holding both stocks and bonds, were rated against all funds from the first three buckets.)

This approach had the advantage of being independent of how funds were categorized, so that the ratings were unaffected by such decisions, but the disadvantage of being highly prone to "style effects." If, for example, the leading technology companies strongly outgained the broad U.S. market, as was the case until very recently, then almost all large-growth stock funds would receive high star ratings. Conversely, even the most successful small-value funds would not.

In 2002, Morningstar therefore shifted to assigning star ratings by investment category (which, predictably, led to lobbying by fund companies to have their funds placed into what they believed would be the most favorable categories). That change ameliorated the style-effect problem, but, as we shall shortly see, did not eliminate it.

From Penthouse to Doghouse

The star ratings initially were treated reverently. It was the era of "star managers" (a phrase that preceded Morningstar's existence). Investors widely believed that although top investment managers might struggle temporarily, when the markets moved against them, their skill eventually would triumph. Consequently, the star ratings were thought to be relatively permanent. Once a 5-star manager, always a 5-star manager, although perhaps with some bumps along the way.

Over time, investors--and Morningstar researchers--learned otherwise. Because they were generated on up to 10 years' worth of performance, the star ratings were stable from month to month, but they frequently changed over longer time periods. This occurred even after the calculation's 2002 revision. Many top-rated funds subsequently languished.

The pendulum then swung markedly in the opposite direction. "Morningstar Star Rankings Fail Mutual Fund Investors," stated one article. Asked an academic paper, "Kiss of Death: A 5-Star Morningstar Mutual Fund Rating?" A third article advised flatly, "Ignore Morningstar's Stars."

Such warnings were helpful, as the star ratings had become too popular. For example, when funds dropped a star, many investors would sell, believing that Morningstar had "downgraded" those investments. Of course, that was not the case; the rating was a calculation, not an analyst's judgment. Also, the rating might have declined because a strong result from 10 years ago rolled off the fund's record, rather than because of recent weakness.

Differing Signals

However, the criticisms of the star rating misstated the problem. Some--as with the "Kiss of Death" paper--suggested that the stars consistently failed, such that the top-rated funds underperformed, while the low-rated funds outperformed. Not only were such implications false, but they wouldn't have been problems if they had been true, because reversing the ratings would have made them usefully predictive. Buy 1-star funds, avoid 5-star funds, profit.

Others argued that the star rating's predictions are unreliable. Sometimes low-rated funds shine--although mostly not, because they are on average the costliest funds, and that extra cost generates an ongoing headwind--sometimes there are no patterns, and sometimes top-rated funds triumph. That claim is correct. If you are asked, "Will the 5-star funds outperform the 1-star funds over the next five years?," the appropriate response is, "That is likelier than the alternative, but I certainly cannot guarantee it."

Generally missed, though, is that the star rating's results are often predictable in hindsight. This occurs because of those pesky style effects. The 2002 methodology change ensures that there will always be as many 5-star large-growth stock funds as 1-star funds. However, if large-growth stocks lead the market for several years, the ratings within the category will be persistent, because the "purest" large-growth funds will continually perform best, while the "watered down" large-growth funds--that is, those funds that border other categories--will lag.

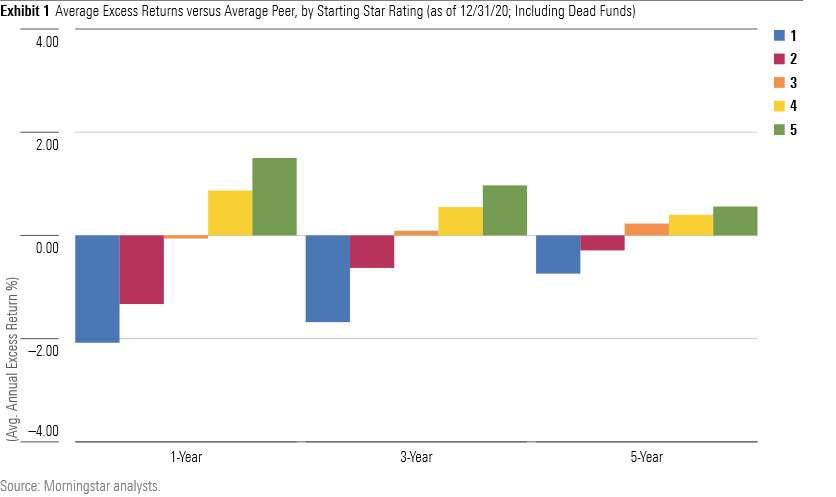

That, in fact, is what has recently occurred. As shown by Morningstar's Jeff Ptak in "Past Performance Has Been Predictive Lately. Wait, What?," the star ratings assigned to mutual funds in January 2016 aligned with subsequent results. Over the next five years, 5-star funds outgained 4-star funds, which in turn beat 3-star funds, and so forth. That transpired because, broadly speaking, the previous market conditions persisted. Funds that had previously benefited from their style effects continued to do so, and vice versa.

Wrapping Up

The SEC requires funds to disclose that "past performance does not guarantee future results." Commonly, this warning is reworded as implying something stronger. For example, one website states that "past performance is no indicator of future performance." That is taking the caution too far. There are times when past results do correlate with future results, and when that happens, the star rating--along with other historic performance measures--can be predictive.

Whether investors can identify such conditions before they occur, of course, is another story.

John Rekenthaler (john.rekenthaler@morningstar.com) has been researching the fund industry since 1988. He is now a columnist for Morningstar.com and a member of Morningstar's investment research department. John is quick to point out that while Morningstar typically agrees with the views of the Rekenthaler Report, his views are his own.

The opinions expressed here are the author’s. Morningstar values diversity of thought and publishes a broad range of viewpoints.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/T2LGZCEHBZBJJPPKHO7Y4EEKSM.png)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-18-2024/t_34ccafe52c7c46979f1073e515ef92d4_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

/d10o6nnig0wrdw.cloudfront.net/04-09-2024/t_e87d9a06e6904d6f97765a0784117913_name_file_960x540_1600_v4_.jpg)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/1aafbfcc-e9cb-40cc-afaa-43cada43a932.jpg)