Why I'm Lukewarm on Real Estate

With correlations trending up, REITs aren't as compelling as they used to be.

I last wrote about real estate investment trusts in February 2020, but a lot has changed since then. In this article, I'll explain why REITs can still fill a role in a portfolio but aren't necessarily a must-have for diversification.

Diversification Benefits Waning

As with my previous article, I'll focus on investing in equity real estate securities, primarily real estate investment trusts. REITs are companies that own and/or operate real estate properties, including shopping malls and other retail outlets, office buildings, warehouses, apartment buildings, and hotels.

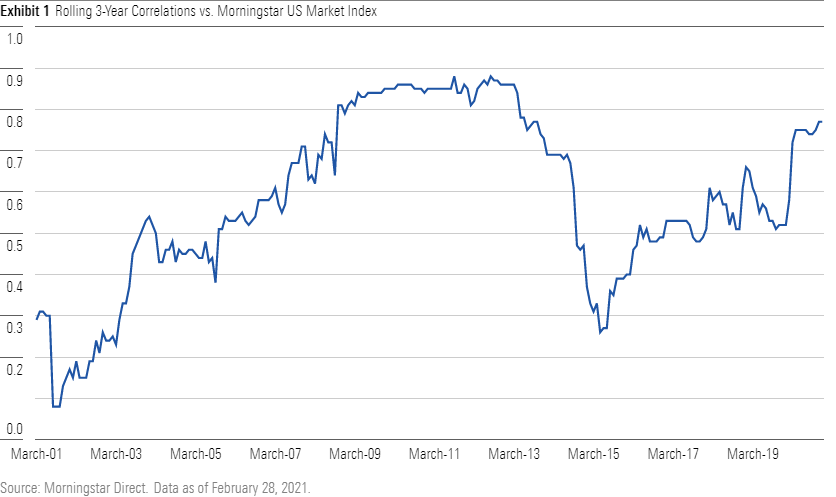

Because its performance can be highly cyclical and idiosyncratic, real estate has generally had a lower correlation with both equities and fixed-income securities than most other asset classes. Over the period from 1972 through Feb. 28, 2021, the correlation between the FTSE Nareit Equity REITs Index and the S&P 500 averaged about 0.59. (A correlation of 1.0 would indicate two assets moving in perfect lock step, and zero would indicate no correlation).

However, correlation patterns often change over time. Since 1975, the rolling three-year correlation between REITs and the broader equity market has been as low as 0.08 (in early 2001) and as high as 0.86 (in 2010). As with many areas, correlations tend to trend higher during periods of market stress and lower returns, making diversification tough to find when investors need it most.

This pattern held true as early 2020 as correlations spiked amid the coronavirus-driven market downturn. Thanks to the abrupt drop-off in economic activity and fears about the negative impact of longer-term shift toward remote working, REITs lost about 41.5% in the COVID-19 bear market in early 2020. For the full year, the Morningstar US REIT TR Index had a correlation coefficient of 0.94 when measured against the broader equity market--the highest it's been since 2011. Over the past three years, REITs have also moved fairly closely in step with large-cap stocks, with a three-year correlation coefficient of 0.75.

That makes REITs significantly less attractive from a diversification perspective. It's possible that correlations could trend back down, but it's unclear if and when that could happen.

Yield Advantage Eroding

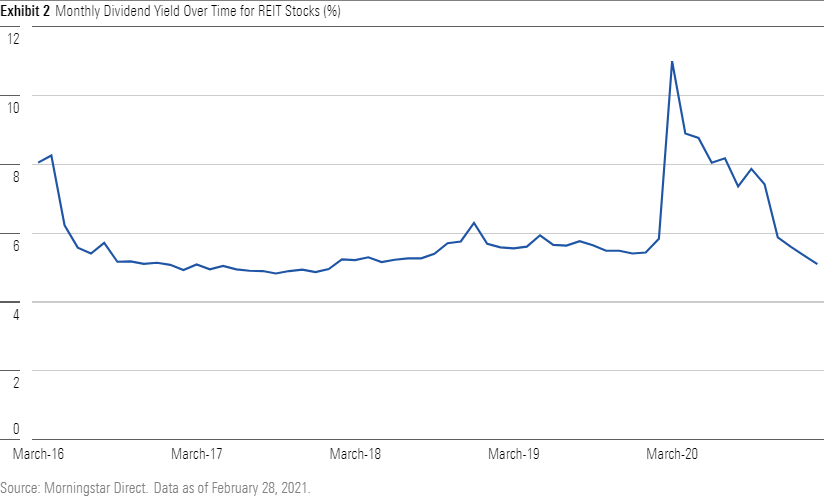

REITs also look less attractive from a yield perspective than in the past. Because they're required to distribute nearly all their income to shareholders, REITs can offer above-market dividend yields. At the individual equity level, U.S.-based stocks in the real estate sector paid out an average yield of 7.26% over the trailing 12-month period ended December 2019. Yields spiked in early 2020 as investors sold off REITs but have come down considerably since then. The average REIT stock had a monthly dividend-yield payout of about 5% as of February 2021, down from as high as 11% in early 2020.

Current yields are also on the low end relative to long-term averages, and yields for funds are even lower. The average real estate fund has paid out 2.6% over the past 12 months. That compares favorably with current yields for the S&P 500 and the 10-year Treasury bond, which were both about 1.5% as of March 4, 2021, but it's not a huge advantage. Lower fund yields partly reflect the drag of underlying expenses, which average about 0.8% for real estate mutual funds and exchange-traded funds.

Valuation is a closely related issue. Yields have declined because of rising prices on the underlying stocks, making them less attractive from a valuation perspective. Morningstar equity analysts have found a few pockets of value in real estate (including Macerich MAC, Cushman & Wakefield CWK, and Simon Property Group SPG), but the average stock in our coverage universe was trading at a 10% premium to estimated fair value as of March 4, 2021.

The Case for Real Estate

There are still a few arguments in favor of real estate, namely its potential value as an inflation hedge. Because property owners can pass along most increases in their underlying costs to tenants by raising lease prices, real estate boasts a built-in inflation hedge. It can also benefit from greater demand during periods when surging economic growth leads to higher inflation. From 1972 through the end of 1979, for example, inflation averaged about 8% per year in the United States. The FTSE Nareit All Equity REITs Index posted average annual returns of 10.6% over the same period, outpacing both inflation and the broader equity market.

However, it's not clear if real estate will maintain be able to guard against inflation as well in the future. Weaker demand for commercial office space and other REITs in the wake of the global pandemic could make it tough for property owners to pass along price increases to their tenants, at least in the short term. If inflation starts creeping up from the low levels we've seen over most of the past decade, it's not clear if real estate will perform as well as it did during previous periods of above-average inflation.

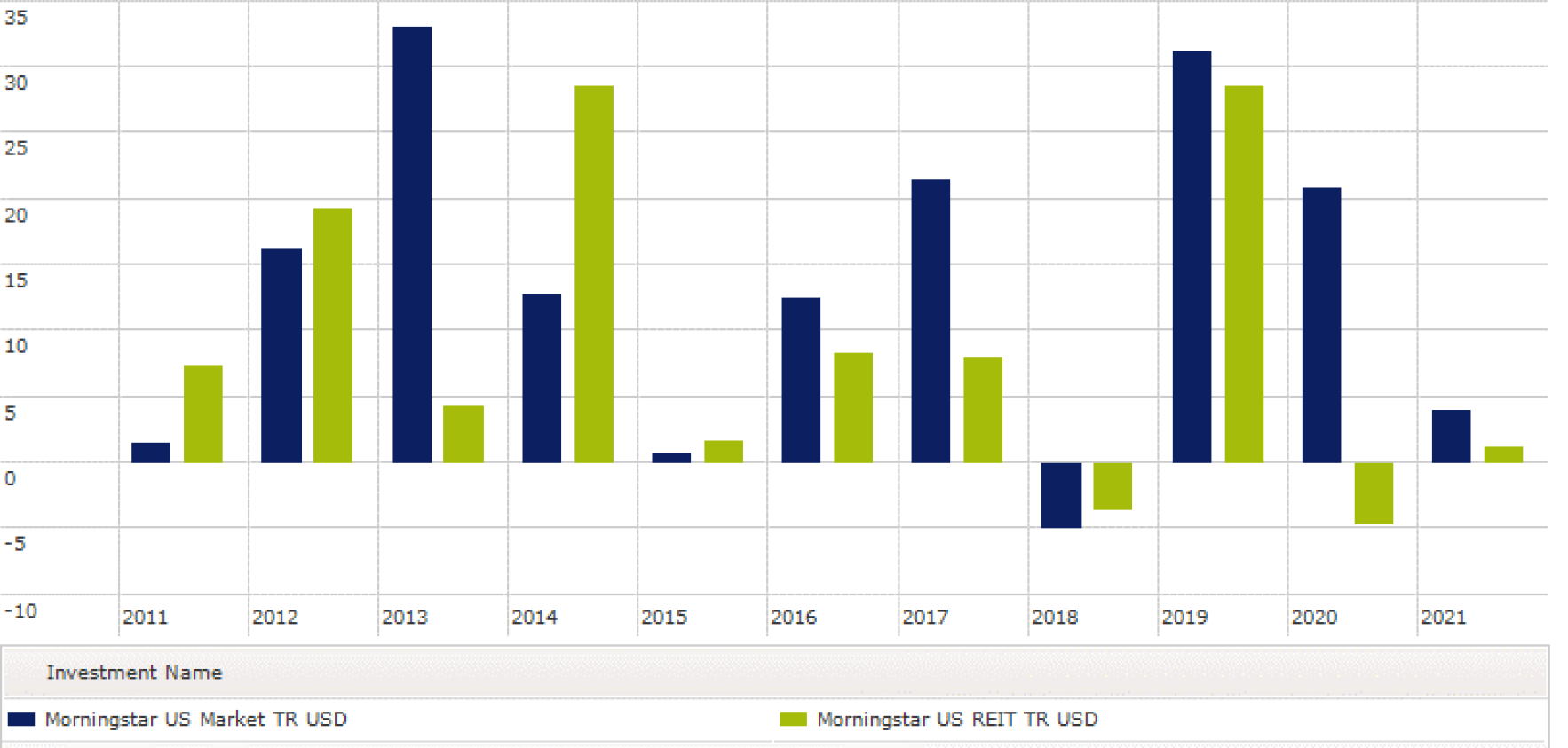

Real estate still has a long-term performance advantage, but you have to go back pretty far to see it. After bouncing back nicely in the wake of the 2007-08 financial crisis, real estate has lagged the broader market more often than not. As mentioned above, the coronavirus-driven bear market in early 2020 was particularly painful for REITs. REITs have since gained back most of their losses, but performance has still lagged the broader equity market in four out of the past five calendar years.

Exhibit 3: Calendar-Year Returns (%) for Real Estate vs. Broad Equity Market

Source: Morningstar Direct. Data as of Feb. 28, 2021.

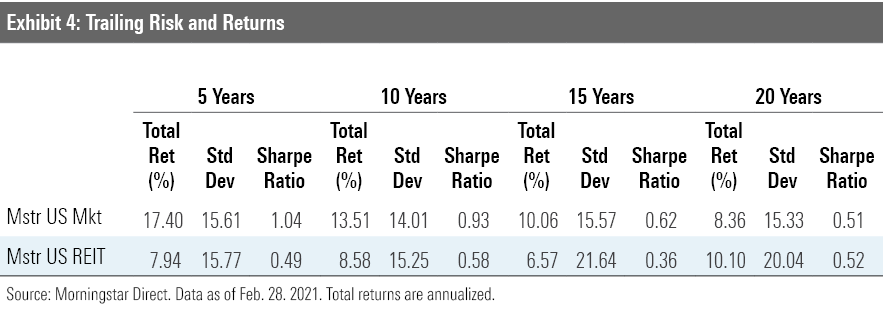

As a result, the Morningstar US REIT TR Index offered both lower returns and higher risk over most trailing periods ended in February 2021, with the exception of the trailing 20-year period. Over the period from March 2001 through February 2021, the Morningstar US REIT TR Index posted annualized returns of 10.1% per year, compared with 8.4% for the broader equity market.

Real estate is both highly cyclical and subject to periodic downturns, as the deep losses in early 2020 made clear. In the past, REITs have always managed to rise from the ashes; the industry made a strong rebound after the 1990 banking crisis and after suffering double-digit losses in both 2007 and 2008. As the economy recovers from the pandemic-driven recession, some real estate subsectors, such as hotels and apartment REITs, could experience strong demand. The outlook for other areas is more mixed, though. In commercial real estate, for example, our analysts are anticipating a potential secular drag on demand owing to growth in remote work.

Finally, investors who own large-cap equity funds already have some exposure to real estate, as stocks in the sector make up about 2.5% of broad market indexes such as the S&P 500. With correlations significantly higher than in the past and industry fundamentals uncertain, it's hard to make a case for carving out an additional allocation.

Disclosure: Morningstar, Inc. licenses indexes to financial institutions as the tracking indexes for investable products, such as exchange-traded funds, sponsored by the financial institution. The license fee for such use is paid by the sponsoring financial institution based mainly on the total assets of the investable product. Please click here for a list of investable products that track or have tracked a Morningstar index. Neither Morningstar, Inc. nor its investment management division markets, sells, or makes any representations regarding the advisability of investing in any investable product that tracks a Morningstar index.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WC6XJYN7KNGWJIOWVJWDVLDZPY.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/HHSXAQ5U2RBI5FNOQTRU44ENHM.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/737HCNGRFLOAN3I7RKGB7VPEKQ.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)