Will the Real Retirement Income Number Please Stand Up?

Is the 4% rule too high, too low, or just right?

Retirement is supposed to be a well-deserved break after the pressures of the working world, but that doesn’t mean it’s easy. One of the toughest parts can be figuring out how much you can safely spend during retirement. If you take out too much, you run the risk of running out of assets later in life, especially if you’re fortunate enough to enjoy a long life span. If you take out too little, you might miss out on some of the fruits of a lifetime of savings, such as travel, dining out, gifting money to charity or family members, or spending more on leisure activities. Pinning down a number that’s neither too high nor too low is notoriously difficult, and the stakes are high.

Even retirement experts often disagree on the “right” number for retirement withdrawals. The 4% rule--which assumes that retirees set an initial withdrawal rate equivalent to 4% of the starting portfolio value and adjust the previous year’s withdrawal amount each year for inflation--has been widely adopted by financial advisors and individual investors. But there has also been debate about whether withdrawals should ratchet down (to account for lower market returns) or up (to account for lower inflation), as well as the need for more flexible systems that don't assume a fixed withdrawal rate.

In this article, I’ll dig into the key assumptions behind the different estimates and what they mean for retirees. Assuming that future market returns are lower than in the past, an initial withdrawal rate closer to 3.5% looks like a reasonable starting point.

The Origins of the 4% Rule

Bill Bengen's landmark study, published in 1994, was notable because it stress-tested withdrawal rates based on return patterns over actual historical periods (instead of relying on average returns over time). He examined each 30-year period with starting dates from 1926 through 1976, adjusting withdrawals for each year's actual inflation rate. Based on this data set, he concluded that for a portfolio combining 50% stocks and 50% bonds, a 4% withdrawal rate never fully depleted the portfolio's value, even during some of the worst periods such as 1928 through 1957 and the 1973-74 bear market.

However, some observers argued that because it's based on testing worst-case scenarios, the 4% rule could be considered overly conservative. Michael Kitces looked at historical returns going back to 1871 and concluded that while a 4% withdrawal rate worked for a 60/40 portfolio in every scenario, actual sustainable withdrawal rates varied significantly (from 4% to 10%, with a median of about 6.5%) over different 30-year periods. As a result, retirees relying on the 4% rule would have often ended up with large remaining portfolio balances at the end of retirement.

Similarly, Jonathan Guyton argued in a 2004 paper that a 65% equity weighting combined with a more dynamic withdrawal strategy could produce safe withdrawal rates as high as 5.8% to 6.2%.

Too High, Too Low, or Just Right?

In 2013, Morningstar's David Blanchett--along with Michael Finke and Wade Pfau-- published a paper arguing that the 4% withdrawal rate is unsustainable in an era of lower bond yields. Because there's a strong correlation between bond yields and future total returns, record-low interest rates imply significantly lower fixed-income returns.

In 2020, Pfau published another article about the need to ratchet down withdrawals given lower bond yields. He looked at this issue using bond yields in March 2020 as a starting point. (At that time, the 10-year Treasury was yielding about 0.8%). He also assumed that stocks maintain their historical average risk premium of 6 percentage points per year over bonds, which also implies lower future stock returns. Based on these return assumptions plus a 2% assumption for inflation, he came up with a 2.4% estimate for sustainable withdrawal rates for a portfolio combining 50% stocks and 50% bonds. That would effectively reduce the dollar amount of first-year withdrawals by about 40% for new retirees--a $16,000 reduction for a $1 million portfolio.

On the other hand, Bill Bengen himself has expressed the view that lower inflation should allow for more generous withdrawal rates, suggesting a number as high as 5.25% to 5.5%. In an October 2020 podcast with Michael Kitces, Bengen said that because previous withdrawal-rate estimates were based on worst-case scenarios, higher numbers should be sustainable in a low-inflation environment like we've had recently. In 2020, for example, inflation was only 1.4% compared with closer to 3% per year historically. A more benign inflation rate has significant implications for retirement spending. While Bengen didn't elaborate on the return assumptions behind the higher figures, I came up with similar numbers by keeping stock and bond returns in line with their historical averages, increasing the equity allocation to 60% of assets, and reducing inflation to 1.4% per year.

In fact, a low-inflation environment is one of the reasons a 4% withdrawal rate would have still been sustainable over the worst 30-year return stretch we’ve experienced to date: the period from 1929 through 1958. Retirees during that period would have watched their portfolios suffer through the Great Depression, the bear market in 1937, and World War II. As a result, nominal returns for a 50/50 balanced portfolio averaged only 6.4% per year. But inflation was also unusually kind to retirees, averaging 1.8% over the 30-year period.

In particular, a deflationary trend toward the beginning of the term helped offset the effects of an adverse sequence of returns. While the market suffered double-digit losses from 1929 through 1931, inflation also dropped below zero. As a result, retirees adjusting their withdrawals for inflation would have reduced withdrawal amounts in dollar terms. If inflation had been more normal--in line with the 2.9% historical average--the portfolio would have been depleted after about 25 years.

Wading Into the Debate

It should be clear by this point that the only answer to the “right” number for sustainable withdrawal rates is both vague and unhelpful: It depends. But we can make some educated guesses to test a plausible scenario. There’s no question that lower bond yields don’t bode well for future fixed-income returns. At the same time, high equity market valuations suggest the possibility of lower stock-index returns going forward. To account for both of these scenarios, we used real (inflation-adjusted) returns on stocks and bonds as a starting point but reduced the arithmetic averages for both asset classes by 200 basis points. That leads to average real return assumptions of about 7% for stocks and 0.4% for bonds.

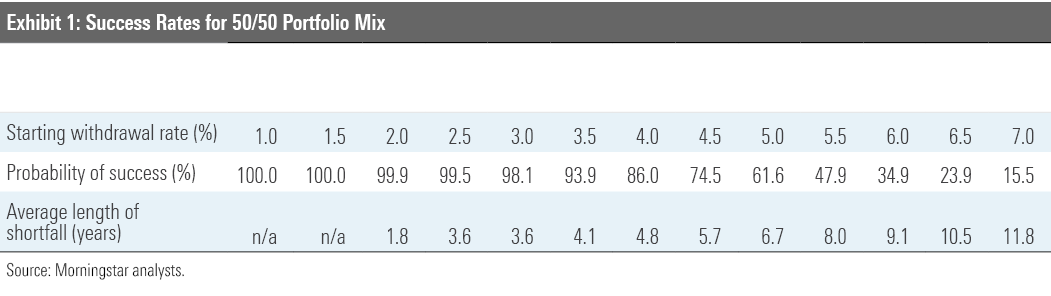

To get a better sense of how portfolio results might play out with different withdrawal levels, my colleague Maciej Kowara used the real return assumptions above as a baseline (keeping volatility and correlation assumptions in line with the historical averages) and tested various initial withdrawal rates over a 30-year time horizon. He then ran a Monte Carlo analysis to randomly generate 10,000 potential return paths for each spending rate to generate a range of scenarios and estimate the probabilities of different outcomes.

As shown in Exhibit 1, these assumptions lead to a slightly lower sustainable withdrawal rate for a portfolio combining 50% stocks and 50% bonds. An investor looking for a 90% probability of success wouldn’t quite get there with the traditional 4% initial withdrawal rate, but ratcheting starting withdrawals down to 3.5% improved the odds. The table also shows the average length of the shortfall for portfolios that ran out of money before the end of the 30-year period.

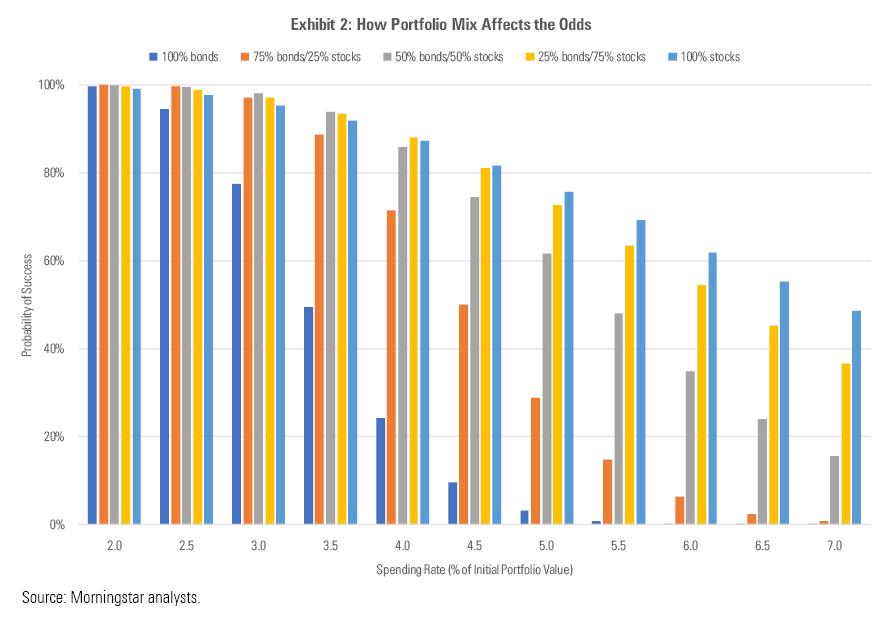

Portfolio mix is another important factor. Increasing the portfolio’s equity allocation can improve the odds of success, as shown in Exhibit 2. Conversely, bond-heavy portfolios can put a damper on sustainable withdrawal rates. Depending on their level of comfort with equity market volatility, retirees can use equity exposure as a lever to allow for slightly higher withdrawal rates.

Of course, this analysis comes with a couple of major caveats. Longevity is inherently uncertain, so most retirees can’t predict how long they’ll need their money to last. And even if we could pin down an accurate return number, how retirees ultimately fare depends on a multitude of factors, including the sequence of returns. A negative sequence of returns during the first few years of retirement can be especially detrimental.

That means it’s important to monitor market conditions and portfolio values over time. Most retirees don’t set a fixed withdrawal amount that they follow year in and year out no matter what. Instead, investors can improve their results by implementing a more flexible withdrawal strategy, such as not adjusting withdrawals for inflation in years following a negative market return or limiting withdrawals to a certain percentage of the portfolio’s value.

Conclusion

Still, you need a starting point. For retirees who plan to start taking withdrawals soon, it’s reasonable to be on the conservative side with assumptions for future returns. If returns over the next 30 years end up being a bit lower than in the past, the safest path would be to adjust withdrawal rates accordingly.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/360a595b-3706-41f3-862d-b9d4d069160e.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/WDFTRL6URNGHXPS3HJKPTTEHHU.png)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/EC7LK4HAG4BRKAYRRDWZ2NF3TY.jpg)

:quality(80)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/BZ4OD6RTORCJHCWPWXAQWZ7RQE.png)