How Effective Would Baby Bonds Be as Monthly Payments?

It depends on how the money is used.

Would a lump sum of cash all at once or regular monthly installments over time work better for mitigating inequality? Morningstar dives in to weigh the pros and cons of each when applied to baby bonds.

Sen. Cory Booker and Rep. Ayanna Pressley recently reintroduced a bill called the American Opportunity Accounts Act. Co-sponsored by 15 senators, including Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, the bill would create a seed savings account of $1,000 for every child at birth, with additional deposits of up to $2,000 each year, depending on household income.

The funds, commonly referred to as baby bonds, would earn interest through investments in 30-year U.S. Treasury bonds. At age 18, account holders could access the funds for allowable uses, such as buying a home or paying for school. While the funding for later contributions still needs to be determined, the entire program is estimated to cost around $60 billion annually.

Proponents of the bill argue that despite not directly factoring race into the equation of who receives these funds, it will significantly reduce the wealth gaps between Black and white households.

Indeed, Morningstar has found that a baby-bond bill could reduce the gap in nonhousing equity wealth between Black and white households to 25%. While the advocates of this policy assume people will take their baby bonds and spend them in short order on education or homes, we wanted to examine whether the bonds themselves can be converted into a meaningful stream of income.

Most Policy Proposals Address the Income Gap Rather Than the Wealth Gap

Unlike with baby bonds, which are designed to level the playing field for children turning 18 and starting to achieve independence, most policy proposals focus on the income gap instead of the wealth gap.

For example, Sen. Mitt Romney has proposed a bill called the Family Security Act that would give each family $3,000 per child, per month. The cap on receiving funds would be set at five children per family and gradually phase out at higher income levels. President Joe Biden, on the other hand, has proposed expanding the child tax credit.

In some ways, these approaches are an inverse of the baby-bond bill in providing a regular income stream up to age 18 and then being terminated versus granting account holders access to all of the funds once they reach that same age.

What if Baby Bonds Were Turned Into an Income Stream?

Under the current proposal, baby bonds are distributed in a lump sum and offer the most value when invested in a return-bearing asset or human capital, such as a college education or courses to acquire a marketable skill.

An alternative would be to turn baby bonds into an income stream once bondholders turn 18. This would assist individuals in handling emergencies, accumulating human capital, and even starting businesses--the same activities touted as potential benefits of a universal income.

If distributed as an income stream, the baby bond (which would be means-based, not universal) would not be consumed as a lump sum, which could be an advantage given that a longer period is conducive to more deliberative--less impulsive--spending.

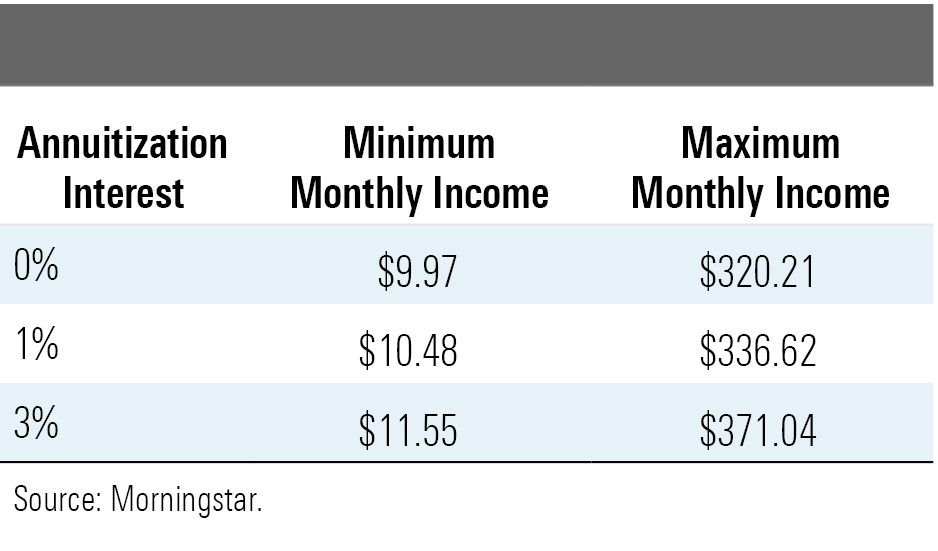

Morningstar conducted an analysis of turning a baby bond into a 10-year immediate annuity. In this approach, payments are distributed over a period of 10 years, starting when the child turns 18. Depending on the income of the household, the payment could range from $11 to $370 monthly (assuming a 3% annual return). Under the 10-year immediate annuity approach, $131 would be the median monthly payment.

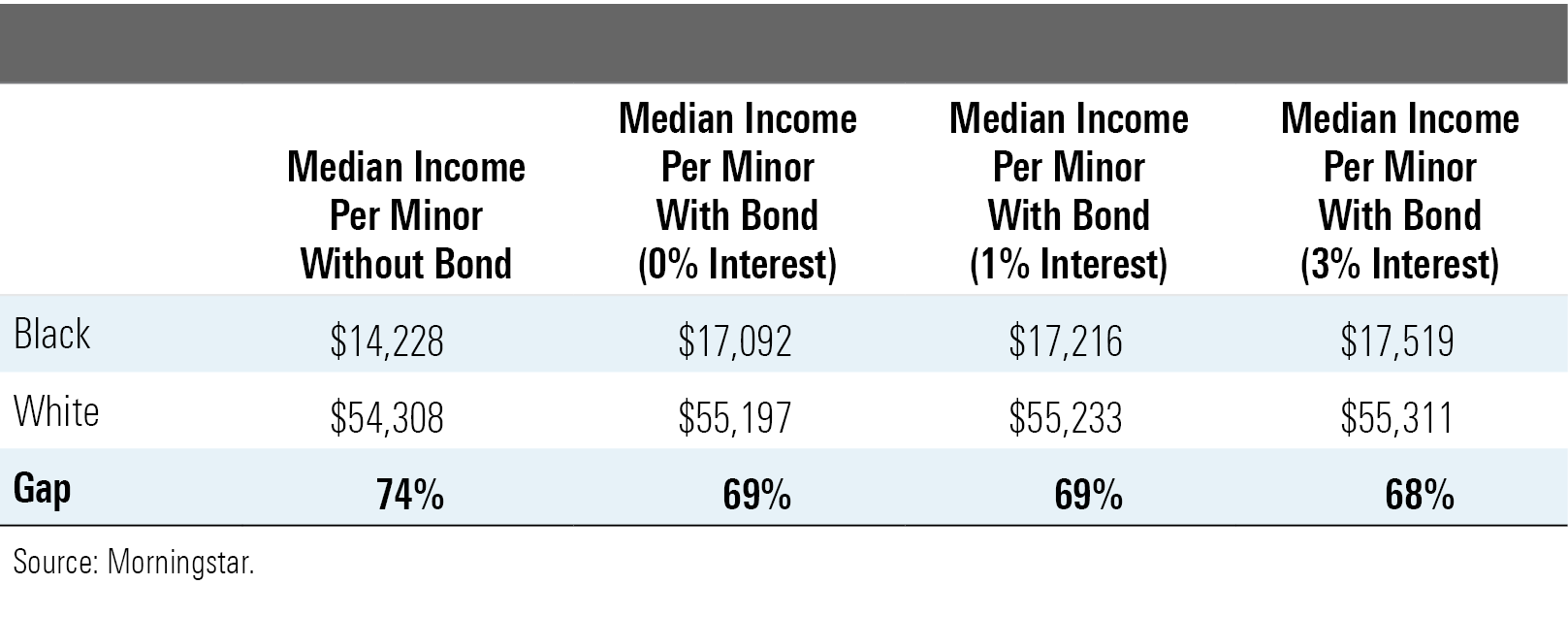

We found that the gap between Black and white median incomes per minor child reduces from 74% to 68%, assuming a 3% market return (see tables below for different simulations).

Monthly payment ranges depending on the assumed interest:

Race economic gap differences are not only influenced by money but also by differences in skills, access to networks, and time available to invest in capital. To the extent that these income payments can be utilized to cultivate human capital skills, networks, and generate time for productive activities (for example, by alleviating childcare or other responsibilities), they will be more effective in closing the income gap on a long-term basis than distributing the money without focusing on these related areas.

While this reduction does not present a significant change to the income gap, these monthly payments could help offset emergencies for which half of American households don't even have $400 saved to account for, according to the Federal Reserve. Additionally, they could improve access to courses to improve human capital or simply help build a savings account for later use.

The Ultimate Goal of Baby Bonds

Baby bonds can help level the playing field for 18-year-olds as they begin their adult lives, but most likely not through the money alone. Making the most of baby bonds may not be a matter of whether they are distributed as income or wealth but rather how the money is used.

A holistic approach--such as coupling the money with counseling on ways to build a future with it--would help disadvantaged youth increase their human capital or open other opportunities that are otherwise unavailable. This pairing of baby bonds with other services may be just as important in achieving the ultimate goal of reducing racial inequalities as determining the means of distributing the money--either as a regular income stream or lump-sum amount.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/f3c31470-cc00-45ac-b20f-d2928ec12660.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/G3DCA6SF2FAR5PKHPEXOIB6CWQ.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VUWQI723Q5E43P5QRTRHGLJ7TI.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/XLSY65MOPVF3FIKU6E2FHF4GXE.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/f3c31470-cc00-45ac-b20f-d2928ec12660.jpg)